First Nations people with asthma

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) First Nations people with asthma, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 28 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). First Nations people with asthma. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/first-nations-people-with-asthma

MLA

First Nations people with asthma. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 14 December 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/first-nations-people-with-asthma

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. First Nations people with asthma [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 28]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/first-nations-people-with-asthma

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, First Nations people with asthma, viewed 28 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/first-nations-people-with-asthma

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Page highlights

- Asthma is a long-term lung condition that is caused by narrowing of the airways when they become inflamed.

- Health risk factors for asthma include smoking, being overweight or obese or insufficiently active.

How common is asthma amongst First Nations people?

Around 128,000 (16%) First Nations people reported having asthma in 2018–19, down from 18% in 2012–13.

What is the impact of asthma on First Nations people?

- First Nations people with asthma were 2.5 times more likely to report having ‘poor’ health compared with people without asthma (18% and 7.2% respectively).

- Asthma was the 4th leading cause of non-fatal burden among First Nations people aged 45 and under.

- During 2017–21, there were 65 deaths due to asthma among First Nations people in Australia.

Treatment and management of asthma in First Nations people

- There were 1,800 hospitalisations for First Nations people with a principal diagnosis of asthma in 2021–22 (200 per 100,000 population).

- In 2021–22, there were 5,400 emergency department presentations for First Nations people with asthma (605 per 100,000 population).

Comorbidities of asthma in First Nations people

In 2018–19, 62% of people with asthma had at least one other chronic condition – the top 3 comorbidities were arthritis (51%), mental and behavioural conditions (46%), and back problems (37%).

What is asthma?

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways which presents as episodes of wheezing, breathlessness and chest tightness due to widespread narrowing of the airways (NACA 2022). It can be triggered by viral respiratory infections, exercise, allergens, smoking and air pollutants (AIHW 2023b).

According to the 2018–19 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health survey (NATSIHS), asthma was the third most commonly reported long-term condition affecting First Nations people (16%) after long and short-sightedness (20% and 31%) and anxiety (18%). Asthma was the most common chronic respiratory condition reported by First Nations people (ABS 2019).

First Nations people with asthma often experience poor health and high morbidity rates (Skinner et al. 2020). This may be due to exposure to specific risk factors, such as smoking (in particular secondhand smoke exposure in infants and children) as well as a lack of access to culturally appropriate asthma education and health service delivery (Campbell et al. 2021; Brock and McGuane 2018).

People with asthma who also have Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Many adults with asthma also have features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This is collectively described as ‘asthma+COPD’ and ‘asthma-COPD overlap’ (GINA 2023).

Symptoms of these chronic inflammatory diseases are similar, but there are some important differences (Yayan and Rasche 2016). Asthma is characterised by intermittent, reversible airflow obstruction, whereas COPD tends to be associated with persistent and irreversible airflow obstruction. Childhood asthma may also be a risk factor for COPD (GINA 2023; McGeache 2018).

According to the ABS 2018–19 NATSIHS, 24% of First Nations people aged 45 and over with asthma also had COPD, compared with 5.5% of First Nations people without asthma.

Health risk factors associated with asthma

While the underlying causes of asthma are still not well understood, there is evidence that certain health risk factors may be associated with an increased risk of flare-ups (AIHW 2023c; GINA 2023; Campbell et al. 2021).

Some health risk factors may increase the chance of developing asthma in the first place (either in childhood or as an adult) or may increase the likelihood that a person with asthma will develop additional health problems.

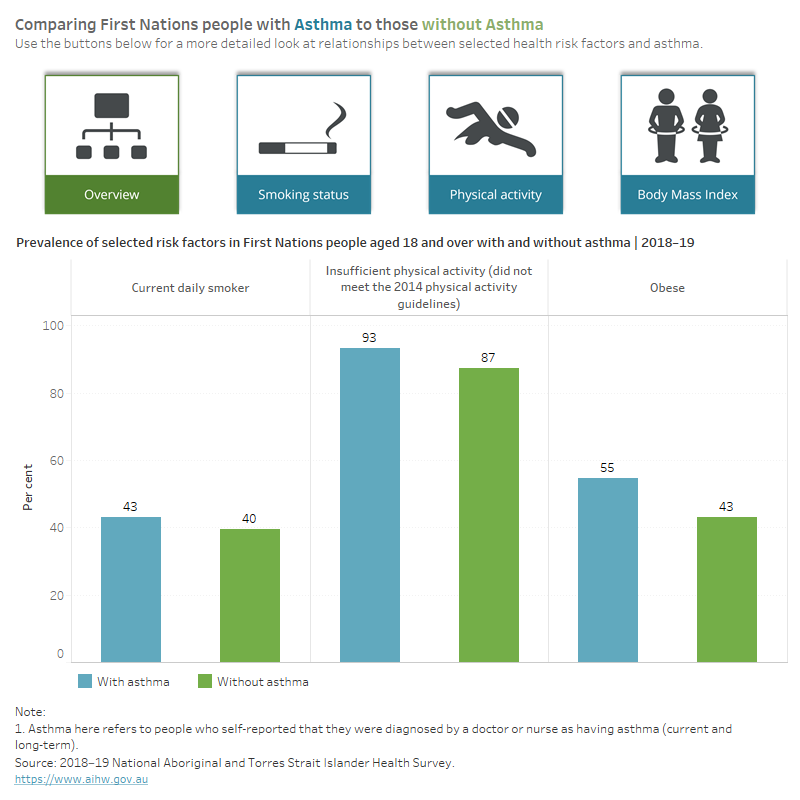

Based on the 2018–19 NATSIHS, First Nations people with asthma were:

- almost as likely to be a current daily smoker compared with people without asthma (43% and 40%, respectively)

- more likely to be insufficiently active (not meeting the 2014 physical activity guidelines) compared with people without asthma (93% and 87%, respectively)

- 1.3 times as likely to live with obesity compared with people without asthma (55% and 43% respectively) (Figure 1).

For support to quit smoking, speak to your GP or call the Quitline (13 7848).

Figure 1: Selected health risk factors reported by First Nations people aged 18 and over with and without asthma, 2018–19

How common is asthma amongst First Nations people?

Around 128,000 (16%) First Nations people reported having asthma, based on the 2018–19 NATSIHS, down from 18% in 2012–13 (ABS 2019).

Prevalence by age and sex

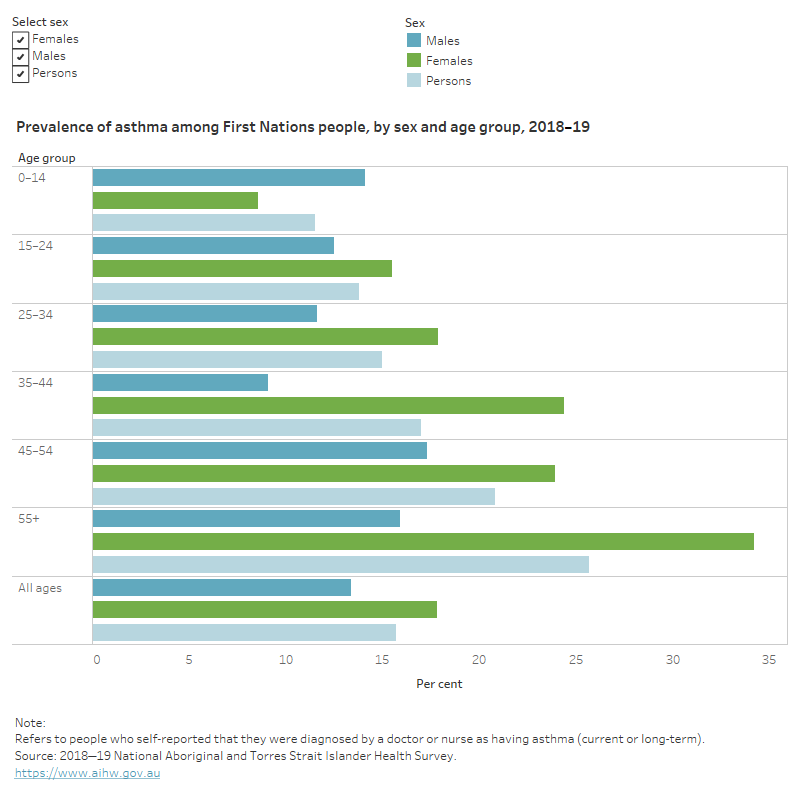

Based on 2018–19 NATSIHS, the prevalence of asthma:

- was higher among females compared with males (18% and 13%, respectively) (ABS 2019)

- increased with age, from 12% in children aged 0–14 to 26% in those aged 55 and over

- was 1.6 times as high for boys compared with girls (aged 0–14) (14% and 8.6%, respectively)

- was 2.1 times as high for females compared with males aged 55 and over (34% and 16%, respectively) (Figure 2).

This change in prevalence for males and females in adulthood is likely due to a complex interaction between changing airway size and hormonal changes that occur during adolescent development, as well as differences in environmental exposures (Dharmage et al. 2019; Zein et al. 2019).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 population groups, First Nations people were 1.6 times as likely to report having asthma as non‑Indigenous Australians (18% and 11%, respectively).

Figure 2: Prevalence of asthma among First Nations people, by age and sex, 2018–19

This figure shows that females aged over 55 years had the highest prevalence of asthma, while females aged 0–14 and males aged 35–44 had the least.

Prevalence by remoteness area

Remoteness structure

Remoteness is classified according to the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure, July 2016 (ABS 2018). Remoteness Areas divide Australia into five classes of remoteness on the basis of a measure of relative access to services. The five remoteness classes are: Major Cities, Inner Regional, Outer Regional, Remote and Very Remote.

These remoteness areas are centred on the Accessibility Remoteness Index of Australia, which is based on the road distances people have to travel for services (ABS 2018).

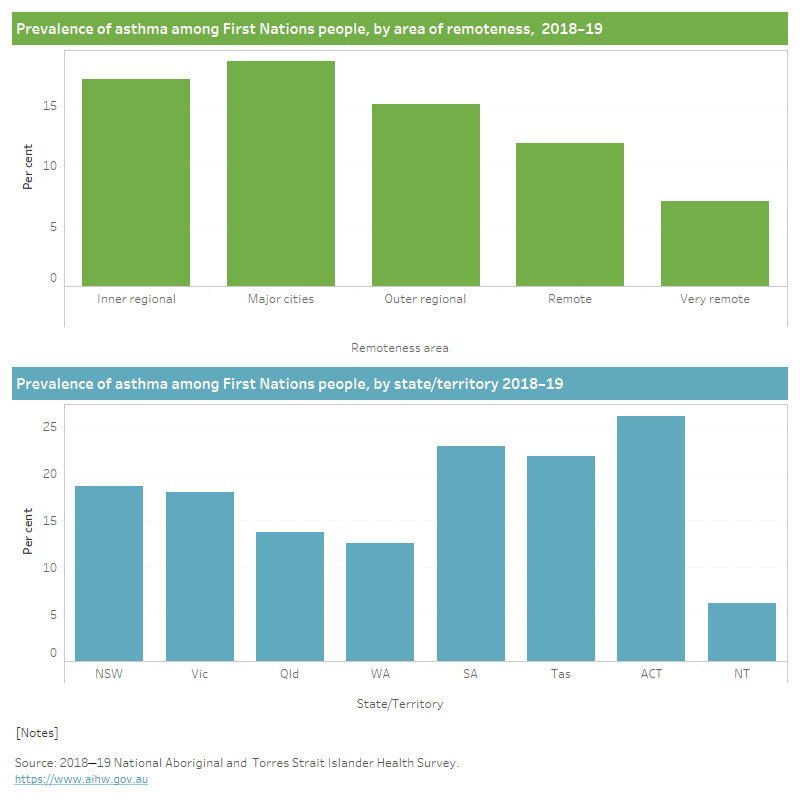

Based on 2018–19 NATSIHS, First Nations people living in Major cities were most likely to have asthma (19%). Asthma prevalence decreased with increasing remoteness overall, with those living in Remote (12%) and very remote (7%) areas the least likely to report having asthma (Figure 3).

This finding is consistent with evidence suggesting that the burden of current asthma is higher among First Nations people living in non-remote communities compared with those living in remote communities (Brock and McGuane 2018).

Prevalence by state and territory

In 2018–19, First Nations people living in the Australian Capital Territory reported the highest rates of asthma (25%), followed by those in South Australia (23%) and Tasmania (22%). First Nations people in the Northern Territory were the least likely to have asthma (6%) (Figure 3).

For more information on respiratory conditions in First Nations people, see the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Measure 1.04 (AIHW 2023a).

Figure 3: Prevalence of asthma among First Nations people, by remoteness, state and territory, 2018–19

This figure shows that the prevalence of asthma did not vary between those living in Inner and Outer regional areas and those living in NSW and Vic.

What is the impact of asthma on First Nations people?

Asthma has varying degrees of impact on the physical, psychological, and social wellbeing of people living with the condition, depending on disease severity and their level of control.

Having well-controlled asthma can alleviate the impact of asthma on daily life. Asthma is described as well-controlled when there are few symptoms and little reliever use (for example, less than 2 days/week), and no night waking or limitation of activity (AIHW 2023b).

How does asthma affect quality of life?

Health-related quality of life is a measure used to describe an individual’s perception of how a disease or condition affects their physical, psychological and social wellbeing.

Asthma symptoms can lead to fatigue, exhaustion, poor sleep quality which can in turn be related to discomfort, distress, and functional limitations (Nelson et al. 2017). Functional limitations experienced by people with asthma include decreased ability to complete daily activities, physical activity limitation, loss of productivity at work or study (Vermeulen et al. 2016; Hiles et al. 2018; Toyran et al. 2020). This can often result in withdrawal from social, community and occupational activities (Foster et al. 2017).

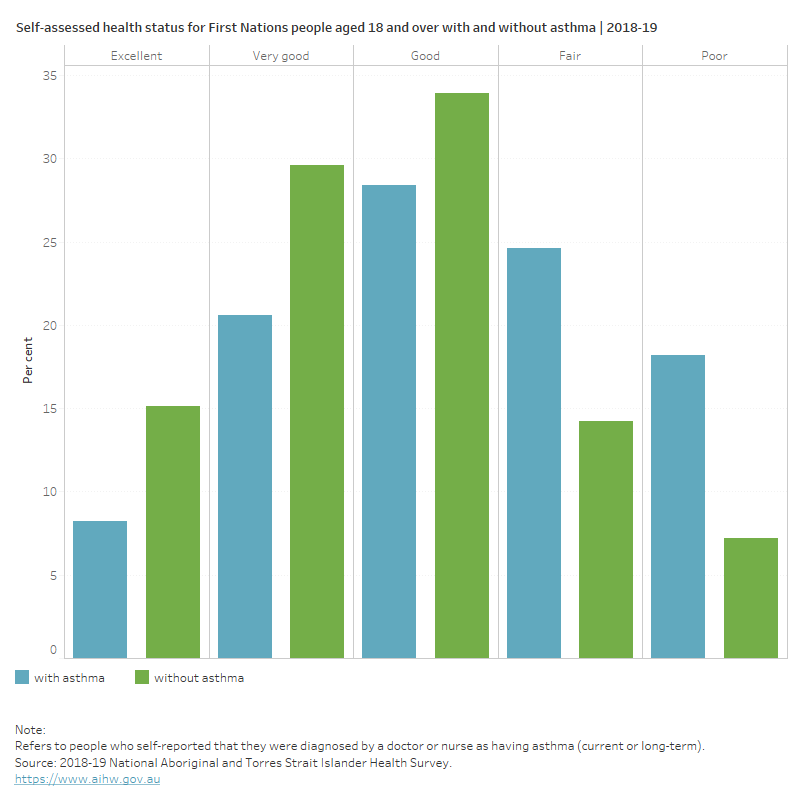

According to 2018–19 NATSIHS, First Nations people aged 18 and over with asthma were:

- 2.5 times as likely to report having poor health compared with people without asthma (18% and 7.2%, respectively) (Figure 4)

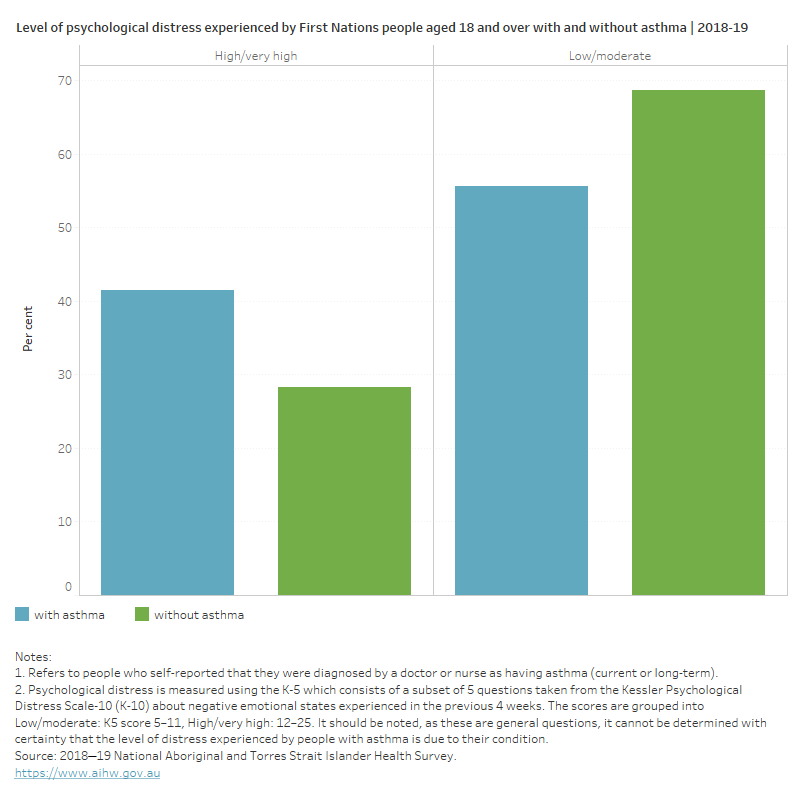

- 1.5 times as likely to experience high and very high levels of psychological distress compared with those without asthma (42% and 28%, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Self-assessed health status for First Nations people aged 18 and over with and without asthma, 2018–19

This figure shows that 8% of those with asthma, compared with 15% of those without, reported having excellent health.

Figure 5: Level of psychological distress experienced by First Nations people aged 18 and over with and without asthma, 2018–19

This figure shows that 56% of those with asthma, compared with 69% of those without, experienced low and moderate levels of psychological distress.

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

According to the Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018 report, asthma was the 7th leading cause of the total disease burden, accounting for 3.4% of total DALY, after:

- coronary heart disease (5.8%)

- anxiety disorders (5.3%)

- suicide and self-inflicted injuries (4.6%)

- alcohol use disorders (4.4%)

- depressive disorders (4.3%)

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (3.4%).

The burden of asthma was greater in females compared with males (4.3% compared with 2.5%, respectively).

The disease burden of asthma was mostly non-fatal burden. In 2018, asthma was the 4th leading cause of non-fatal disease burden (5.7% of total YLD) after:

- anxiety disorders (10%)

- depressive disorders (8.1%)

- alcohol use disorders (7.8%) (AIHW 2022a).

How many deaths were associated with asthma?

First Nations people experience higher mortality from chronic lower respiratory diseases (such as asthma, bronchiectasis, emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) than non-Indigenous people in Australia (AIHW 2023a; Australian Indigenous HealthinfoNet 2018).

Mortality data for First Nations people are reported for 5 jurisdictions for which the quality of First Nations identification in the deaths data is considered to be adequate, namely, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory (AIHW 2023a).

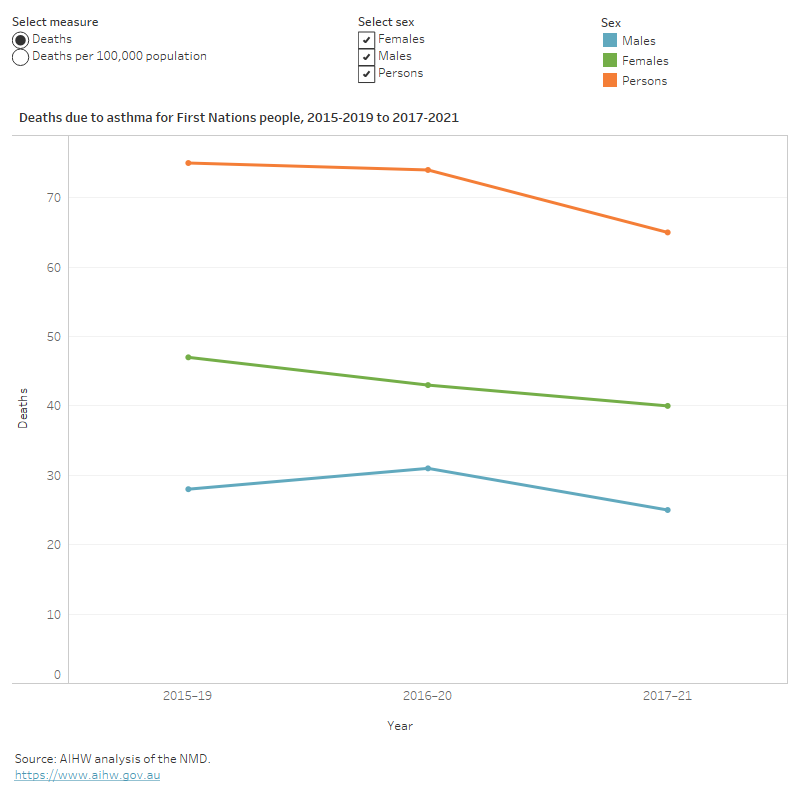

In the 5-year period from 2017–2021, there were 65 deaths reported in 5 jurisdictions (noted above), corresponding to a mortality rate of 1.7 deaths per 100,000 population.

Asthma mortality rates:

- increased with age, from 0.2 deaths per 100,000 population in children aged 0–14 to 6.6 deaths per 100,000 population in those aged 65 and over

- were 1.6 times as high for females compared with males (2.1 and 1.3 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 6).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 population groups, asthma mortality rates for First Nations people were 1.9 times as high as for non‑Indigenous Australians (2.5 and 1.3 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Trends over time

Over the following 5-year periods 2015–2019, 2016–2020 and 2017–2021, asthma mortality rates:

- decreased from 2.1 to 1.7 deaths per 100,000 population

- were consistently higher for females compared with males (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Deaths due to asthma for First Nations people, by sex, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2015–2019 to 2017–2021

This figure shows that between 2015–2019 and 2017–2021, the asthma mortality rate decreased by 19%.

Treatment and management of asthma in First Nations people

There is no cure for asthma, so management of the disease and its symptoms is the primary form of treatment (NACA 2022). To ensure that First Nations people with asthma receive optimal care for their asthma, the Australian Asthma Handbook recommends:

- culturally secure asthma care

- involvement of First Nations health workers and health practitioners in asthma care (NACA 2022).

Use of medications for asthma

Medication is key in managing symptoms of asthma, helping to reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations. The 2 main types of asthma medicines are relievers and preventers. Reliever inhalers are used for the rapid relief of symptoms when they occur. Preventer medicine is the mainstay of asthma management, to minimise symptoms and exacerbations. Inhaled corticosteroids are the most used preventers.

A relatively new class of medications known as biologics are also being increasingly prescribed to those with severe asthma. Biologics act like preventers but are not classified as such (AIHW 2023b).

According to the 2018–19 NATSIHS, of First Nations people with asthma or symptoms in the last 12 months:

- 56% reported using asthma medication within the last 2 weeks

- there was little difference in the use of asthma medications between those living in non-remote areas and remote areas (56% and 55%, respectively) (AIHW 2023b).

For more information about management of asthma, see the Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 2.2: Management for children, adolescents, and adults.

Asthma action plan

National guidelines for the management of asthma recommend a written self-management plan. These should be developed by a health care professional in consultation with the patient to help manage their asthma and reduce the severity of acute flare-ups (NACA 2022). A culturally appropriate written asthma action plan is recommended for First Nations patients.

Templates of specially designed asthma action plans for First Nations people (some written in community languages) are available from National Asthma Council Australia (NACA 2022). These include:

- a Remote Indigenous Australian Asthma Action Plan

- an Every Day Asthma Action Plan (designed for remote Aboriginal Australians who do not use written English).

According to the ABS NATSIHS in 2018–19:

- 32% of First Nations people with asthma had a written asthma action plan

- First Nations people living in non-remote areas were more likely to have a plan compared with those living in remote areas (32% compared with 27%, respectively) (ABS 2019).

What role do hospitals play in treating First Nations people with asthma?

In 2021–22, there were 1,800 hospitalisations with asthma recorded as the principal diagnosis for First Nations people (200 per 100,000 population).

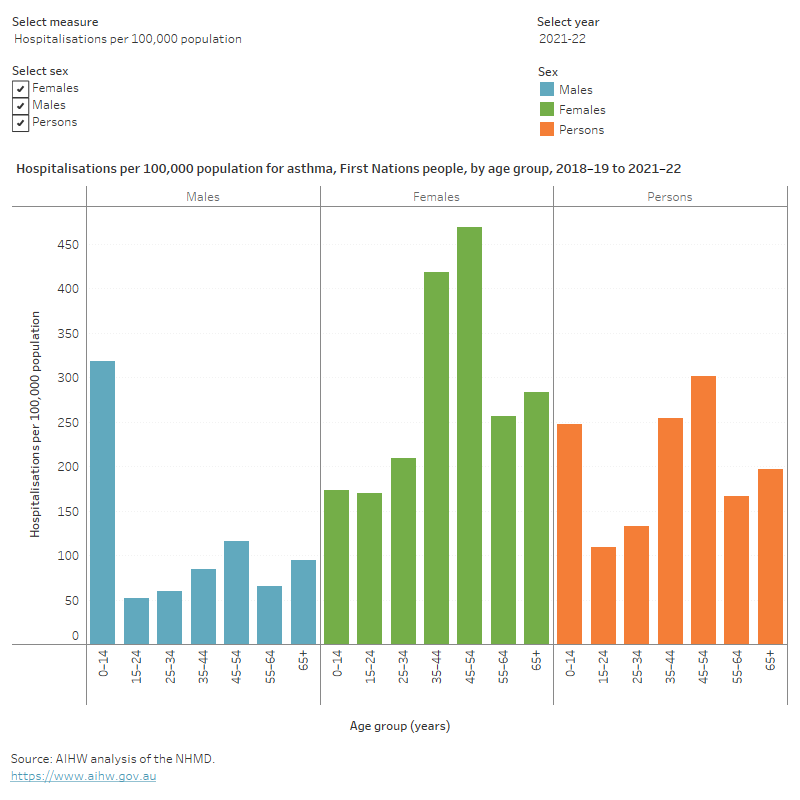

Variation by age and sex

Hospitalisation rates were:

- highest for males aged between 0–14 and for females aged 45–54 (470 and 210 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- 1.8 times as high for boys compared with girls aged 0–14 (320 and 175 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- higher for females compared with males overall (250 and 155 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 7).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 population groups, asthma hospitalisations rates for First Nations people were 2.1 times as high as for non‑Indigenous Australians (205 and 100 per 100,000 population respectively).

The peak observed for women aged 35–54 is also observed for emergency department presentations and is likely to be due to menopause and associated hormonal changes. These changes have been linked to significant consequences on respiratory function (Zein et al. 2019; Asthma+Lung UK 2022).

Figure 7: Hospitalisation rates for asthma in First Nations people, by age and sex, 2021–22

This figure shows that asthma hospitalisation rates were highest for people aged 45–54 and lowest for people aged 15–24.

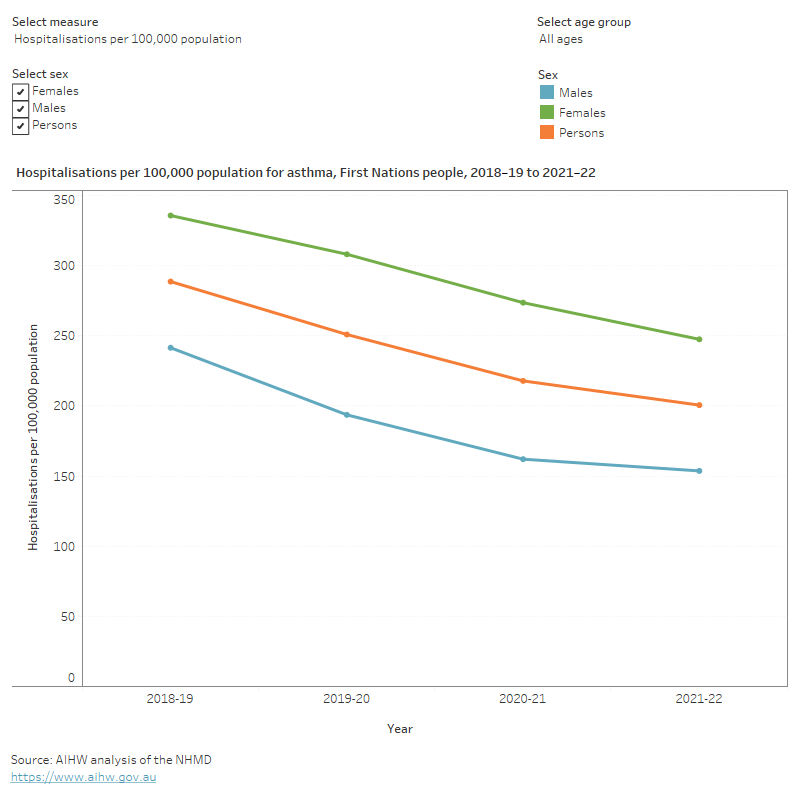

Trends over time

Between 2018–19 and 2021–22, the asthma hospitalisation rates:

- decreased by 30% (from 290 to 200 per 100,000 population)

- were consistently higher among females compared with males, ranging between 1.4 and 1.7 times as high in females (Figure 8).

The rate of hospitalisations over the past few years has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information on this, see the Chronic respiratory conditions COVID-19 impact section.

Figure 8: Hospitalisation rates for asthma in First Nations people, by sex and year, 2018–19 to 2021–22

This figure shows that the decrease in asthma hospitalisation rates were constant at 13% between 2018–19 and 2020–21, followed by a 7% drop in 2021–22.

Emergency department presentations for asthma

Data from the National Non-Admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database (NNAPEDC) show that in 2021–22, there were 5,400 emergency department (ED) presentations for First Nations people with asthma, about 600 per 100,000 population.

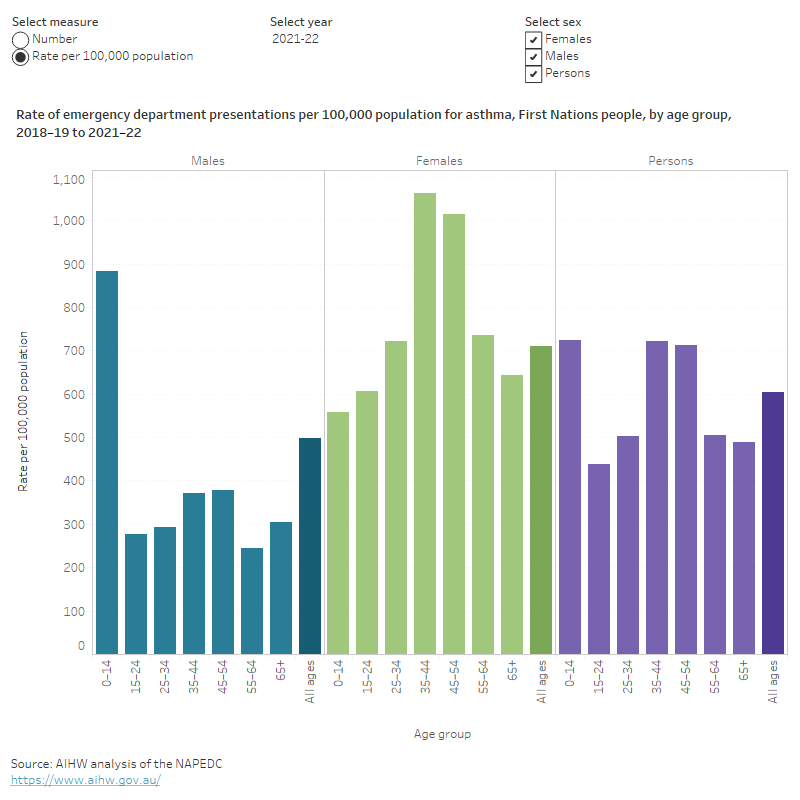

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, ED presentation rates for asthma were:

- highest for males aged between 0–14 and for females aged 35–44 (880 and 1100 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- 1.6 times as high for boys compared with girls aged 0–14 (880 and 560 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- 1.4 times as high for females compared with males for all ages (710 and 500 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 9).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 population groups, emergency department presentations for asthma for First Nations people were 2.6 times as high as for non‑Indigenous Australians (600 and 230 per 100,000 population respectively).

Figure 9: Emergency department presentations due to asthma for First Nations people, by age and sex, 2021–22

This figure shows that the emergency department presentation rates due to asthma were highest for people aged 0–14 and lowest for people aged 15–24.

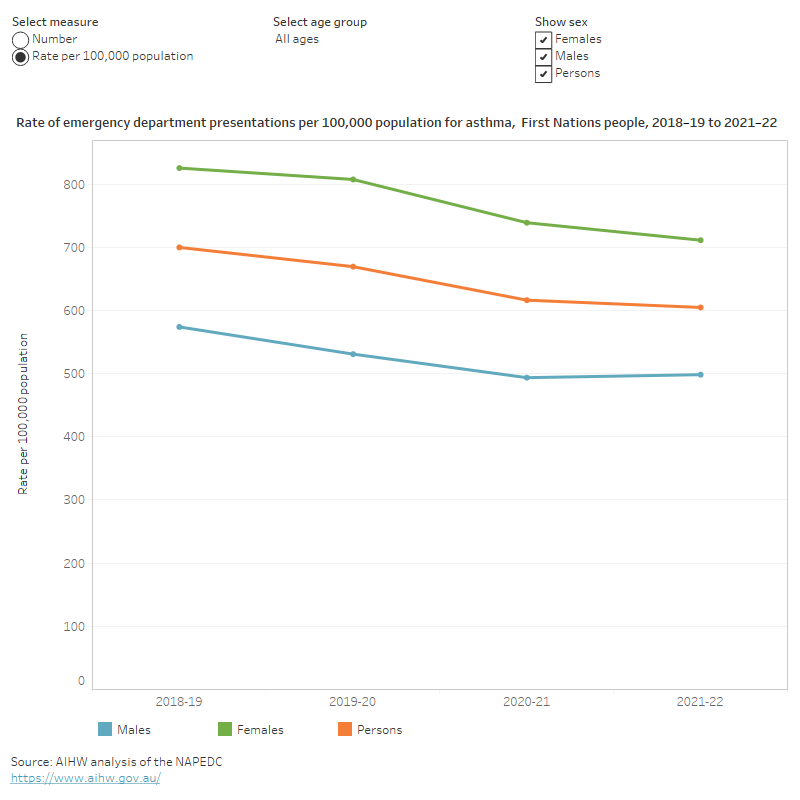

Trends over time

Between 2018–19 and 2021–22, ED presentation rates:

- decreased by 14% (700 to 605 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- decreased for children aged 0–14, from 890 to 720 per 100,000 population

- were consistently higher for females compared with males across all years (Figure 10).

The rate of emergency department presentations over the past few years has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information on this, see the Chronic respiratory conditions COVID-19 impact section.

Figure 10: Asthma emergency department presentations for First Nations people, by sex and year, 2018–19 to 2021–22

This figure shows an 8% decrease in the emergency department presentations due to asthma between 2018–19 and 2020–21 followed by 2% in 2021–22.

Comorbidities of asthma in First Nations people

People with asthma often have other long-term conditions, known as ‘comorbidity’. These other conditions often contribute to severe and difficult-to-treat asthma (GINA 2023; Israel and Reddel 2017).

In First Nations people, the high burden of chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, ear disease, and mental health problems may also affect asthma control and management (AIHW 2023a).

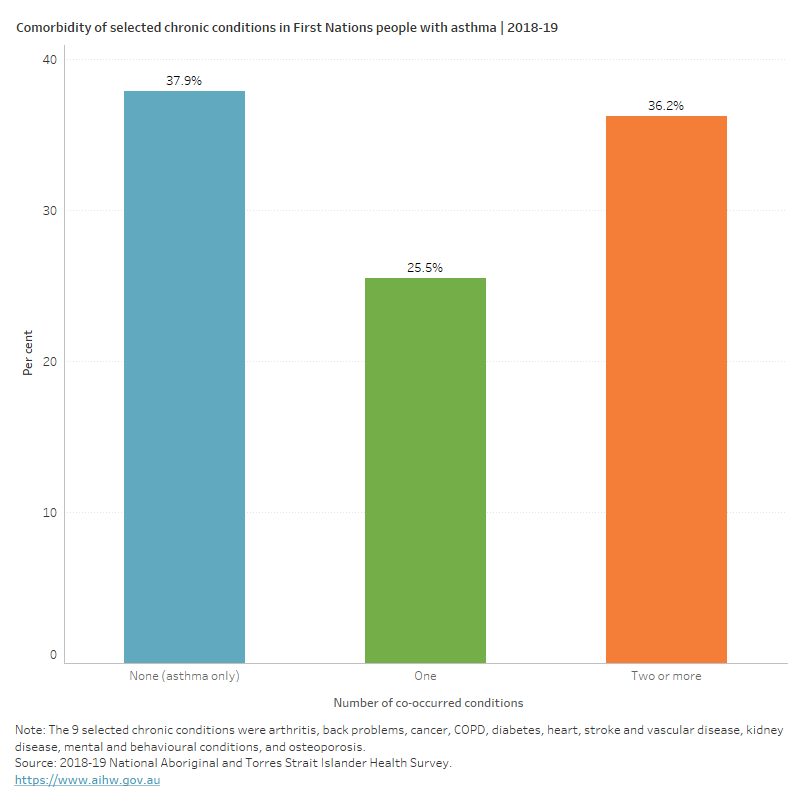

This asthma comorbidity analysis included arthritis, back problems, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart, stroke and vascular disease, kidney disease, mental and behavioural conditions and osteoporosis or osteopenia. These 9 chronic conditions have been selected because they are common in the general community, pose significant health problems, have been the focus of ongoing national surveillance efforts, and action can be taken to prevent their occurrence (ABS 2022).

Based on the 2018–19 NATSIHS, around 79,000 (62%) First Nations people who currently have asthma, also reported having one or more of the selected chronic conditions noted above. Of First Nations people with asthma:

- 26% had one other selected condition

- 36% had 2 or more other selected chronic conditions (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Number of comorbid chronic conditions in First Nations people with asthma, 2018–19

This figure shows that 38% of people who currently have asthma reported not having any other selected chronic condition.

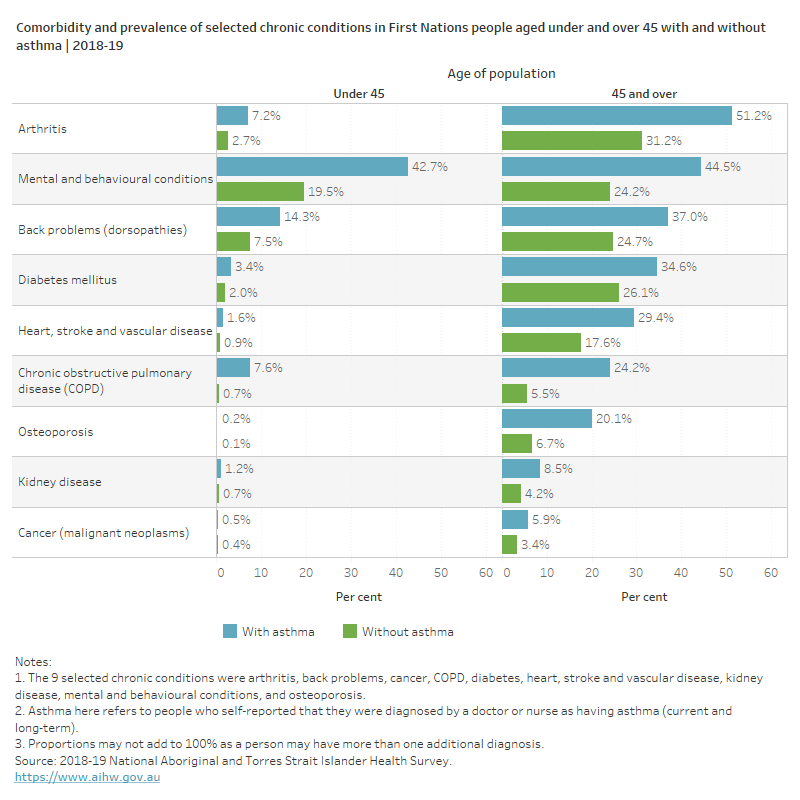

Types of comorbid chronic conditions in people with asthma

Asthma affects people of all ages; however, the prevalence of comorbid chronic conditions differs between people aged under 45 and those over 45.

According to the 2018–19 NATSIHS, among younger First Nations people (aged under 45) with asthma:

- 43% had mental and behavioural conditions (compared with 20% of those without asthma)

- 14% had back problems (compared with 8% of those without asthma)

- 8% had COPD (compared with 1% of those without asthma) (Figure 12).

Among First Nations people aged 45 and over with asthma:

- 51% had arthritis (compared with 31% of those without asthma)

- 46% had mental and behavioural conditions (compared with 24% of those without asthma)

- 37% had back problems (compared with 25% of those without asthma)

- 29% had heart, stroke, and vascular disease (compared with 18% of those without asthma)

- 24% had COPD (compared with 5.5% of those without asthma)

- 20% had osteoporosis (compared with 6.7% of those without asthma) (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Prevalence of selected chronic conditions in First Nations people aged under and over 45 with and without asthma, 2018–19

This figure shows that the reporting of selected chronic conditions was more common in people with asthma aged under 45 than those aged 45 and over.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure, July 2016, ABS Cat. no. 1270.0.55.005. Canberra: ABS, accessed 30 October 2023.

ABS (2019) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19 financial year, ABS Cat. no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS, accessed 9 March 2023.

ABS (2022) Health Conditions Prevalence, 2020-21, accessed 9 February 2023.

Australian Indigenous HealthinfoNet (2018) Summary of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health status 2017, accessed 11 July 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018, Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2023a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: Summary report 2023, Canberra: AIHW, accessed 14 June 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Chronic respiratory conditions, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 June 2023.

Asthma+Lung UK (2022) Asthma is worse for women report, accessed 20 September 2023.

Brock C and McGuanne J (2018) Determinants of asthma in Indigenous Australians: insights from epidemiology – HealthBulletin, Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 18(2), accessed 14 June 2023.

Campbell MA, Winnall WR, Ford C, Winstanley MH (2021) Health effects of secondhand smoke for infants and children, In Greenhalgh, EM, Scollo, MM and Winstanley, MH [editors]. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, accessed 1 November 2023.

Dharmage SC, Perret JL and Custovic A (2019) Epidemiology and asthma in children and adults, Frontiers in Pediatrics 7:246, accessed 7 March 2023.

Foster JM, McDonald VM, Guo M and Reddel HK (2017) “I have lost in every facet of my life”: the hidden burden of severe asthma, European Respiratory Journal, 50: 1700765; doi:10.1183/13993003.00765-2017, accessed 7 August 2023.

GINA (Global Initiative for Asthma) (2023) GINA Main Report 2023, accessed 10 August 2023.

Hiles SA, Harvey ES, McDonald VM, Peters M, Bardin P, Reynolds PN, Upham JW, Baraket M, Bhikoo Z, Bowden J, Brockway B, Chung LP, Cochrane B, Foxley G and Garrett J (2018) Working while unwell: Workplace impairment in people with severe asthma, Clinical and Experimental Allergy, 48: 650–662, accessed 7 August 2023.

Israel E and Reddel HK (2017) Severe and Difficult-to-Treat Asthma in Adults, New England Journal of Medicine, 377: 965–976, accessed 22 August 2023.

McGeache MJ (2018) Childhood asthma is a risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 17(2): 104–109, accessed 10 August 2023.

NACA (National Asthma Council Australia) (2022) Australian Asthma Handbook, Melbourne: National Asthma Council Australia, accessed 3 March 2023.

Nelson LM, Kimel M, Murray LT, Ortega H, Cockle SM, Yancey SW, Brusselle G, Albers FC, Jones PW (2017) Qualitative evaluation of the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with severe asthma, Respiratory Medicine, 126:32–38, accessed 7 August 2023.

Skinner A, Falster K, Gunasekera H, Burgess L, Sherriff S, Deuis M, Thorn A, Banks E (2020) Asthma in urban Aboriginal children: A cross-sectional study of socio-demographic patterns and associations with pre-natal and current carer smoking, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 56(9): 1448-1457. 10.1111/jpc.14991, accessed 10 July 2023.

Toyran M, Yagmur IT, Guvenir H, Haci IA, Bahceci S, Batmaz SB, Topal OY, Celik IK, Karaatmaca B, Misirlioglu ED, Civelek E, Can D, Kocabas CN (2020) Asthma control affects school absence, achievement and quality of school life: a multicenter study, Allergologia et Immunopathologia, 48(6): 545–552, accessed 23 August 2023.

Vermeulen F, Garcia G, Ninane V and Laveneziana P (2016) Activity limitation and exertional dyspnea in adult asthmatic patients: What do we know?, Respiratory Medicine, doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.003, accessed 7 August 2023.

Yayan J and Rasche K (2016) Asthma and COPD: Similarities and Differences in the Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Therapy, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 910:31–38, accessed 23 August 2023.

Zein J, Denson J and Wechsler M (2019) Asthma over the Adult Life Course: Gender and Hormonal Influences, Clin Chest Med, 2019 Mar;40(1):149-161. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2018.10.009, accessed 20 September 2023.