Housing assistance: why do we need it and what support exists?

International human rights law recognises everyone’s right to adequate housing where they live in security, peace and dignity [12]. Stable housing further supports maintained employment, proper health and nutrition, and improvements in education [4]. Home ownership continues to be a widely held aspiration in Australia providing security of tenure and long-term social and economic benefits to homeowners, though exposing them to some financial risk.

Quick facts

- In 2016–17, one in three (37%) specialist homelessness services (SHS) clients reported accommodation issues as the main reason they sought assistance.

- Two-fifths (40%) of clients seeking SHS assistance had experienced domestic and family violence.

- In 2016–17, the Australian Government provided $1.7 billion to state and territory governments to support the delivery of housing and homelessness assistance.

- In 2015–16, lower income households were spending 21% of their income directly on housing costs, above the average of 14% for all households.

Drivers for households seeking housing assistance

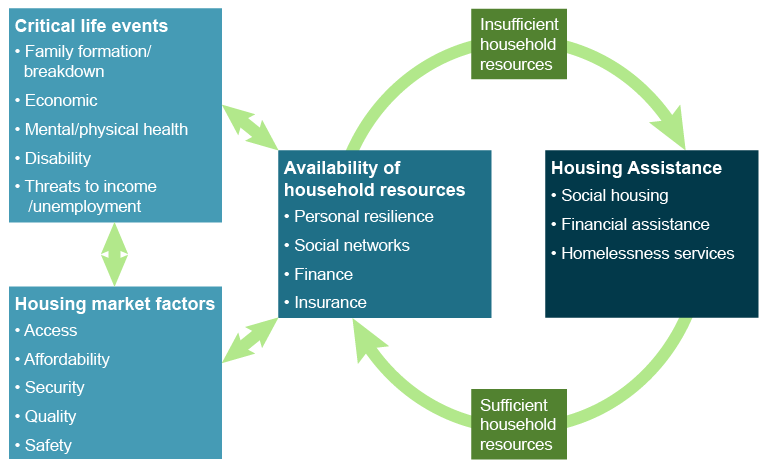

There are many factors that can lead households to seek housing assistance, including critical life events as well as housing market factors, potentially leaving households with limited capacity to manage or avoid the negative impacts of such events (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Drivers of requests for housing assistance

Source: Adapted from Stone et al. 2015 [18]

Critical life events

Critical life events relate to significant developmental milestones that can occur across the lifespan. Positive critical life events, such as the formation of a family or new job opportunities, may lead households to seek housing assistance in their transition to a larger dwelling or a more secure form of housing tenure. Housing assistance also provides support following adverse critical life events such as family breakdown, loss of employment or reduction of income, ill health or loss of loved ones. Research shows that households that experience a number of adverse critical life events, affecting their social and economic circumstances, are more likely to need assistance in accessing or maintaining their housing [17].

Family breakdown

Family dissolution and breakdown can often have a negative impact on home ownership or the ability to sustain a tenancy. Changes in the family structure, particularly separations, often increase the costs of housing by increasing housing mobility due to housing unaffordability or insecurity.

This situation can result in transitions from home ownership or private rental to precarious housing situations and even homelessness. For example, of all clients seeking specialist homelessness services in 2016–17, over half (52%) identified seeking assistance because of the breakdown of interpersonal relationships (including domestic and family violence and/or relationship/family breakdown) [5]. This is an increase from 51% in 2011–12 [6].

Experiencing domestic and family violence

Family, domestic and sexual violence is a major health and welfare issue. It occurs across all ages, and all socioeconomic and demographic groups, but predominantly affects women and children [3]. Housing insecurity can arise when ongoing housing tenure is threatened by experiences of domestic and family violence. Priority groups for social housing allocation include greatest need households under which people can seek housing due to their life or safety being at risk in their accommodation. Applicants falling into this category would include people whose current situation has them experiencing:

- domestic violence,

- sexual/emotional abuse,

- child abuse, or

- the risk of violence or fearing for their safety in their home environment.

Women, particularly single parents, have been found to be more vulnerable to having their housing situation threatened by experiencing domestic and family violence. Two-fifths (40%) or around 114,800 clients of Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) in 2016–17 experienced domestic and family violence, a 7.6 percentage point increase since the Collection began in 2011–12. Of these clients, the majority were female (77%); and more than one-fifth (22%) were children aged under 10 years [5].

Disability

In 2015, around 1 in 5 Australians reported living with disability and 1.4 million Australians reported a ‘severe or profound core activity limitation’ [2]. The demand for housing and support services for persons living with disability is expected to increase as Australia’s population continues to age [2]. This trend has been observed in specialist homelessness services assisting people homeless or at risk of homelessness. In 2016–17, 28,800 people with one or more limitations with a core activity (self-care, mobility, and/or communication) presented to an SHS agency for assistance. Of these, 11,000 reported a severe or profound limitation with a core activity. Appropriate housing and support services in Australia for people living with disability can often be difficult to access or maintain without additional financial assistance [19].

Unemployment

The ability to maintain or gain access to housing is closely linked to households having access to stable, regular employment that provides sufficient resources to cover housing related costs (mortgage or rental payments) [17]. Without this stable regular employment, households may find themselves unable to meet rent and mortgage repayments and in urgent need of housing assistance and services.

Housing market factors

Housing market factors that adversely affect households can lead them to seeking housing assistance. Adverse housing market factors include the inability to maintain current housing costs or limited access to affordable housing. Conflict with landlords, inappropriate housing conditions, difficulty securing new tenancies, and unwanted or frequent housing mobility can also contribute to adverse housing market factors and are strongly related to homelessness [18]. In 2016–17, one in three clients (37%) of specialist homelessness services reported accommodation issues (e.g. housing crisis, inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions, previous accommodation ended) as their main reason for seeking assistance [5].

Housing affordability and stress

Housing affordability refers to a person's ability to meet costs associated with housing, based on their income. A lack of affordable housing puts households at an increased risk of experiencing housing stress, and could force them into decisions that would adversely affect them. Housing stress does not only have financial impacts. It can further result in an exacerbation of stress-related physical and mental health conditions such as:

- Respiratory and psychological conditions aggravated by substandard housing.

- Emotional housing stress due to overcrowding, lack of control, housing tenure, housing costs and residential instability.

- Parental housing stress affecting child wellbeing and health [14].

A common measure of housing stress is where a household's housing costs, primarily mortgage repayments or rents, exceed 30% of their gross income [1]. Both purchasers and renters can be in housing stress. As households on higher incomes may choose to spend a higher proportion of their income on housing, and have more disposable income left over after housing costs, the 30% measure is a better indicator of affordability for low-income households (the bottom 40%), who are more likely to be struggling with housing costs that exceed this benchmark [1].

The latest data from 2015–16 show that on average lower income households were spending 21% of their gross income directly on housing costs (up from 19% in 2009–10), placing them above the average of 14% for all households (also 14% in 2009–10) (Figure 2.2) [1]. Housing costs as a proportion of income were the highest for lower income households renting with a private landlord (32%). However, between 2009–10 and 2015–16, lower income households renting with a state or territory housing authority had the largest change in household costs: from 18% to 24%.

Figure 2.2: Housing costs as a proportion of gross household income, by household type, by tenure type, 2007–08 to 2015–16

Lack of household resources

Households that experience a critical life event or are affected by housing market factors, rely on the household resources (such as savings, assets, family or social networks) to ensure that they are able to access or sustain appropriate housing [18]. Households with low incomes often lack the resources to insure against any negative impacts arising from critical life events and/or housing market factors leading them to require housing assistance.

Additional vulnerabilities

Evidence indicates that vulnerable households, whose insecurity and wellbeing are compounded by their housing situation, are prevalent across all tenure groups, including social and private rental, marginal housing/homelessness sectors and lower income home ownership [17]. Vulnerable groups of policy interest include lower income households with the following characteristics and associated vulnerabilities:

- Older persons (65 years and over)—reduced earning capacity, income restricted by retirement, potential onset of health conditions and the consequential need for particular types of housing and/or housing stability or security.

- Single persons—young singles will tend to have variable incomes and income support profiles which can negatively impact their ability to support stable housing. Older singles usually have their housing security determined by their established tenure type with variability around savings or property wealth in retirement years.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people—financial wellbeing is determined by family/household status, income/employment, and income support and housing similar to other vulnerable groupings however this is coupled with the existent disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

- Lone parents with dependent children—pressures of housing related costs in a single income household when compared to a dual income household during child rearing years. Low income single parent households are found to experience considerable financial disadvantage as they have very little financial reserve once living and housing costs are taken into account.

Noting the policy implications of vulnerable households that may seek housing assistance can strengthen the efficacy of programs implemented in Australia [17].

Housing assistance funding and policy framework

Housing assistance provides a safety net for those experiencing homelessness or who face barriers to sustaining a tenancy in the private rental market [13]. It can further financially support first homeowners entering the housing market avoid significant debt.

Commonwealth funding for social and affordable housing programs within Australia is provided via the National Affordable Housing Special Purpose Payment (NAH SPP) and associated National Agreements between the Commonwealth Government and state and territory governments. In 2016–17, funding was under the National Affordable Housing Agreement (NAHA), which provided a broad framework for the Australian and state and territory governments to improve housing outcomes in all tenure types, as well as to reduce homelessness [15].

As a part of the 2017 Federal Budget, the government is introducing a new National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA) with state and territory governments to increase the supply of new homes and improve outcomes for all Australians across the housing spectrum, particularly those most in need. This new national agreement will:

- include the requirement for concrete outcomes to build more homes and ensure improved housing outcomes across the housing spectrum

- include specific funding for homelessness and provide greater certainty to providers of front line homelessness services [7].

Bilateral schedules with clear targets will help ensure that each state and territory is accountable for better outcomes that recognise their respective different housing markets. These agreements will be underpinned by improved transparency and reporting and are currently being negotiated between the Commonwealth and each state and territory [7].

National agreements, such as the NAHA and NHHA, provide frameworks for all levels of government to work together into the future to improve housing affordability and homelessness outcomes for low and moderate income households [8].

In 2016–17, the Australian Government provided $1.7 billion to state and territory governments to support the delivery of housing and homelessness assistance through the NAHA SPP and related National Partnership Agreements, and $4.4 billion for Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) [15].

State and territory governments also contribute significant funding to support the delivery of housing and homelessness services.

Governments are also trialling new forms of investment approaches, including Social Impact Investment (SII), to drive improved responses to challenging social issues such as homelessness. SIIs are those that intentionally target specific social objectives coupled with a financial return, and measure the achievement of both [16]. In Australia, SII in social and affordable housing supply is a function of government investment in social and affordable housing provision.

The partnerships between private sector, non-government agencies and governments can generate new sources of funding, provide longer-term funding outlooks and, through outcome-based arrangements, offer flexibility in service delivery.

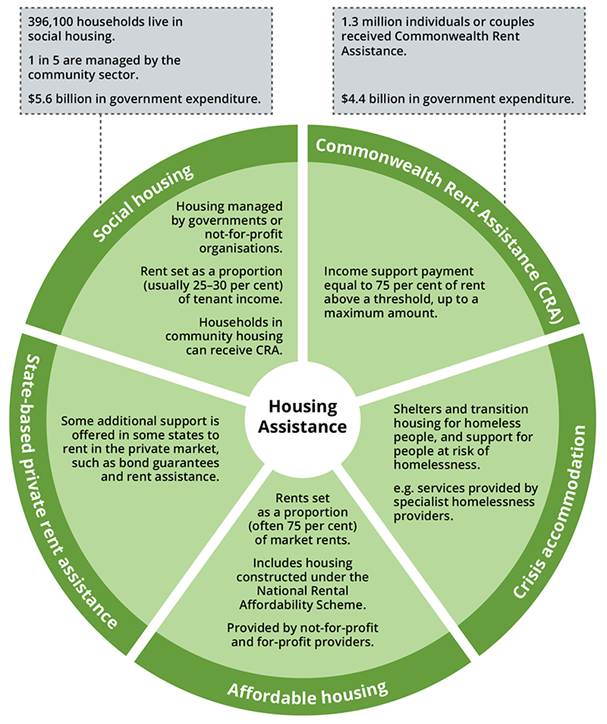

Housing and homelessness assistance programs

Housing assistance can provide vital support when costs associated with accessing or maintaining housing are not able to be met by the household. Housing assistance can be short term or long term and can vary depending on the needs of the individual and/or household. Housing assistance is generally provided through provision of subsidised rental housing (social housing), financial payments (e.g. CRA) and other support for private renters, and through specialist homelessness services. Housing assistance in Australia is provided in many forms (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Primary forms of housing assistance in Australia, 2016–17

Source: Adapted from PC 2016 and SCRGSP 2018 [13,15]

Apart from the primary housing assistance programs, other state and territory-based housing assistance is provided including:

- First Home Owner Grant (FHOG)—a one-off grant payable to low-income first home owners who satisfy eligibility criteria. This was introduced on 1 July 2000 and is funded by the states and territories and administered under their own legislation.

- Home Purchase Assistance (HPA)—a range of financial assistance to eligible households to improve their access to, and maintain, home ownership. This is administered by each jurisdiction.

Governments across Australia also fund a range of services to support people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. These services are provided by government-funded organisations that specialise in delivering accommodation-related and personal support services to people who are homeless or at-risk of homelessness. In 2016–17, around 288,000 people were supported by SHS agencies [5]. Support included social housing tenants seeking assistance from SHS providers to maintain their social housing tenancy. In 2016–17, 1 in 8 (12%) of all SHS clients were in public or community housing when they sought assistance from a SHS agency [5]. The type of support offered to those in social housing is generally through case management and support services, compared to financial assistance for those in private rental. Social housing was provided to 11,000 homeless people assisted through specialist homelessness services in 2016–17. Of these people who were homeless, the most common homeless group assisted into social housing was from short-term/temporary accommodation; 19%, or 5,300 clients in short term/temporary housing were assisted into social housing. This was followed by couch surfers (couch surfing/living in a house with no tenure) (13%), and one in ten (11%) rough sleepers (no shelter or living in improvised or inadequate dwellings) were assisted into social housing. Of all clients who had ended support, over 1 in 5 (22%, or 38,800) were living in public or community housing (38,800 clients), up from 15% at the beginning of support.

For Australians living with disability, a range of options for those who require housing support is available. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has the capacity to provide access to services supporting those with disability to live independently including home modifications, and support with personal and domestic care [11].

For Indigenous Australians, the Indigenous Home Ownership Program (IHOP) helps to facilitate Indigenous Australians into home ownership through providing access to affordable home loan finance. The program aims to address barriers such as loan affordability, low savings, impaired credit histories and limited experience with long-term loan commitments. The IHOP supports the Australian Government’s initiative to provide strong incentives to Indigenous Australians living in remote areas to relocate and take up work in locations where there are stronger labour markets or pursue educational opportunities [10].

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2017. Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2015-16. ABS cat. no. 4130.0, Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2016. Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings 2015. ABS cat. no. 4430.0, Canberra: ABS.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2018. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia, 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2017a. Housing Assistance in Australia 2017. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2017b. Specialist homelessness services report 2016–17. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2012. Specialist homelessness services report 2011–12. Canberra: AIHW.

- COA (Commonwealth of Australia) 2017. Budget 2017–18. Fact Sheet 1.7 A new National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Canberra: CoA.

- COAG (Council of Australian Governments) 2009. National Affordable Housing Agreement: Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations Canberra: COAG.

- Jacobs K, Atkinson R, Spinney A, Colic-Peisker V, Berry M & Dalton T 2010. What future for public housing? A critical analysis. Melbourne: AHURI.

- IBA (Indigenous Business Australia) 2018. Indigenous Home Ownership Program Policy. Canberra: IBA

- NDIS (National Disability Insurance Scheme), 2014. Mainstream interface: Housing and independent living. Fact Sheet. Canberra: NDIS.

- OHCHR (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights) 2014. The right to adequate housing. Human Rights Fact Sheet. Geneva: UN.

- PC (Productivity Commission) 2016. Introducing Competition and Informed User Choice into Human Services: Identifying Sectors for Reform. Study Report. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Rowley S & Ong R 2012. Housing affordability, housing stress and household wellbeing in Australia. AHURI Final Report No. 192. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2018. Report on government services 2018. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Sharam A, Moran M, Mason C, Stone W, & Findlay S 2018. Understanding opportunities for social impact investment in the development of affordable housing - Inquiry into social impact investment for housing and homelessness outcomes. DOI: 10.18408/ahuri-5310202. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Stone W, Parkinson S, Sharam A and Ralston L 2016. Housing assistance need and provision in Australia: a household-based policy analysis. AHURI Final Report 262. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Stone W, Sharam A, Wiesel I, Ralston L, Markkanen S, James A 2015. Accessing and sustaining private rental tenancies: critical life events, housing shocks and insurances. AHURI Final Report No.259. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Wiesel I, Laragy C, Gendera S, Fisher KR, Jenkinson S, Hill T, Finch K, Shaw W & Bridge C 2015. Moving to my home: housing aspirations, transitions and outcomes of people with disability. AHURI Final Report No.246. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.