Housing and housing assistance in Australia

Housing trends in Australia

Housing plays a critical role in the health and wellbeing of Australians. It is vital for people’s social and economic security, associated with positive outcomes for education, employment and finances (SCRGSP 2019). The profile of housing in Australia is changing:

- Most Australians are home owners. In 2015–16, the majority of households were home owners (67%); 37% with mortgage, 30% without (ABS 2017a). Home ownership is still the most common tenure type among the OECD nations (OECD 2017).

- Home ownership rates have dropped, with fewer Australians owning their homes at retirement. There has been a decline in home ownership for those 50–54 years from 80% in 1996, to 74% in 2016. Rates are also dropping for 30–34 year olds (from 64% in 1971, to 50% in 2016) with some not transitioning to home ownership (ABS 2016).

- More people are renting, especially young people. Overall, 31% of Australian dwellings were rented in 2016, compared with 27% in 1991 (ABS 2017b). The proportion of people aged under 35 renting increased from 47% in 2006 to 54% in 2016 (ABS 2016).

- Around one-third of households rent, mostly privately. Where tenure was known, 25% of Australian households rented from private landlords and 4% rented from state and territory housing authorities (ABS 2017a).

- Average household size has decreased, meaning greater demand for more dwellings as the overall population increases. Almost 1 in 4 (24%) households was a lone person household in 2016, up from 1 in 5 (20%) households in 1991 (ABS 2017b).

- Types of dwellings have changed with fewer separate houses. There has been a decrease in the number of occupied separate houses, from 79% in 1991 to 72% in 2016. As of 2016, there was one occupied apartment for every five occupied separate houses (ABS 2017b).

- Around 116,400 people were experiencing homelessness on Census night in 2016. People experiencing homelessness increased from 95,300 in 2001 (ABS 2018).

For more detailed information on home ownership and housing tenure in Australia, see Housing assistance in Australia 2018 (AIHW 2018).

Housing affordability

Access to affordable housing is a key issue for all Australians, but particularly for those on low incomes. A lack of affordable housing puts households at an increased risk of experiencing housing stress and can impact upon their health, education and employment. It can also place people at risk of homelessness (CSERC 2015, SCRGSP 2019). Housing affordability is influenced by a number of factors including a household’s financial situation, the supply, cost and demand in the housing market, government policies and demographic trends.

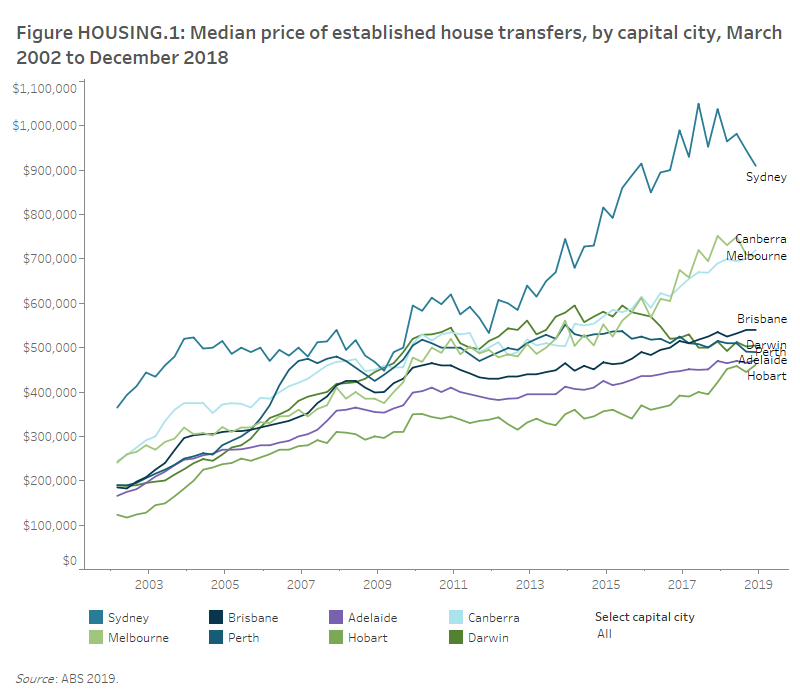

House prices have increased across Australia, however, over the longer term, capital city prices have grown the most. Long-term data shows Sydney and Melbourne have had the steepest rises in the median price of established houses, particularly in the 5 years to 2018, with prices peaking during 2017 and falling more recently (ABS 2019) (Figure HOUSING.1).

This data visualisation displays the median price of established house transfers by capital city over time, March 2002 to December 2018.

There are various ways to measure housing affordability, the simplest is based on the proportion of gross household income spent on housing costs. In Australia in 2015–16, 12% of households spent 30 to 50% of gross income on housing costs with a further 6% spending 50% or more. These proportions have increased from 9% and 5% respectively since 1994–95 (ABS 2017a). This relatively crude measure does not take into account income levels, that is, people earning substantial income may choose to spend more than 30% of their household income on housing, and will have sufficient income to avoid financial stress. For this reason, housing affordability is often focused on households with lower income levels, most commonly households in the lowest two quintiles (or the lowest 40% of income earners). The ‘30/40 rule’ is defined as households in the lowest two quintiles of earners that spend more than 30% of their gross household income on housing costs (Yates 2007). Using this measure, nationally, in 2015–16, nearly 1.0 million low income households were considered to be in financial housing stress. Households with low income in the private rental market were more likely to be in financial housing stress spending on average 32% of income on housing costs, compared with home owners with/without a mortgage (28% and 6% respectively) (ABS 2017a). These figures provide an insight into the number of households potentially at risk of experiencing homelessness due to financial issues, and who therefore may seek government housing assistance.

Drivers for people seeking assistance with housing

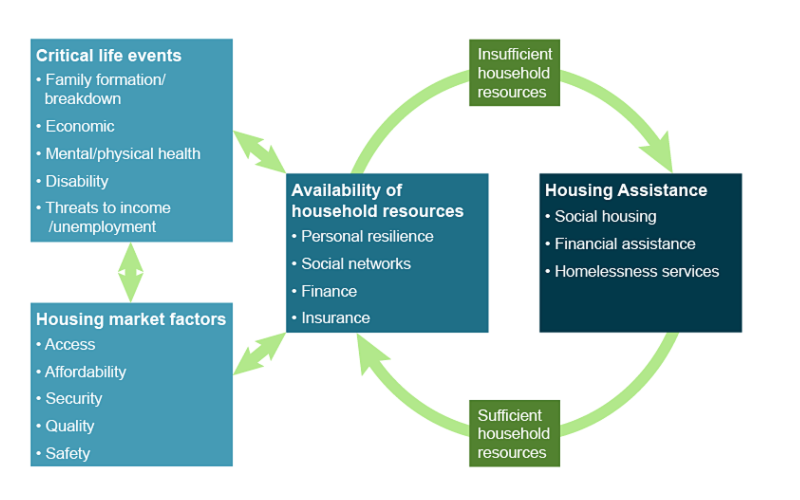

There are many factors that can lead households to seek assistance with housing. Often it is when there are insufficient household resources to manage the impact of critical life events and/or housing market factors (Figure HOUSING.2).

Figure HOUSING.2: Drivers of requests for housing assistance

Critical life events relate to significant life cycle milestones that lead to transitions, for example, the formation/breakdown of a family, ill health (mental or physical) or changes in working arrangements. A critical life event may also be experiencing domestic and family violence. These transitions may involve a need for a larger dwelling, a need for a dwelling in a different location or a more secure form of housing tenure; and in turn, may lead households to seek housing assistance. Research shows that households that experience a number of adverse critical life events, affecting their social and economic circumstances, are more likely to need assistance in accessing or maintaining their housing (Stone et al 2016).

Housing market factors such as limited access, unaffordability, insecure tenure, poor housing quality and limited safety that cannot be mitigated by household resources can be a driver for seeking housing assistance. They include access, affordability, security, quality and safety. These factors are influenced by critical life events, for example some people with severe disability may face limited housing options as a result of increased costs of living, fewer resources and greater need for access to services in close proximity and a secure tenancy. The confluence of these factors can lead people to seeking housing assistance.

Households that experience a critical life event or are affected by housing market factors, rely on the household resources (such as savings, assets, family or social networks) to ensure that they are able to access or sustain appropriate housing (Stone et al 2015). Households with low incomes often lack the resources to insure against any negative impacts arising from critical life events and/or housing market factors leading them to require housing assistance.

For more information on drivers for seeking assistance, see Housing assistance: why do we need it and what support exists?

Types of housing assistance

Housing assistance is important for many Australians who, for a variety of reasons, experience difficulty in securing or sustaining affordable and appropriate housing in the private market. There are a range of programs and these are provided by Commonwealth and state and territory governments as well as community based organisations.

Housing assistance explored throughout this report includes:

- the provision of social housing, owned and managed by government and non-government organisations, including:

- public housing (PH)

- state owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH)

- community housing (CH)

- Indigenous community housing (ICH)

- financial assistance with rental costs for those in the private market, including:

- Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA)

- Private Rent Assistance (PRA)

- financial assistance with home purchase, including:

- First Home Owners Grant (FHOG)

- Home Purchase Assistance (HPA)

- the provision of services to assist in obtaining accommodation or sustaining tenancies, including:

- Specialist Homelessness Services. For information relating to homelessness services, see Specialist homelessness services annual report 2017–18

Other forms of housing assistance

The Indigenous Home Ownership Program (IHOP) helps to facilitate Indigenous Australians into home ownership through providing access to affordable home loan finance. The program aims to address barriers such as loan affordability, low savings, impaired credit histories and limited experience with long-term loan commitments. The IHOP supports the Australian Government’s initiative to provide strong incentives to Indigenous Australians living in remote areas to relocate and take up work in locations where there are stronger labour markets or pursue educational opportunities (IBA 2019).

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) funds Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) for eligible participants with extreme functional impairment or very high support needs when deemed necessary and reasonable. These homes must be built to specific design standards and may be purpose built apartments or free standing dwellings. It is estimated that SDA funding will support 28,000 people across Australia. Prior to the introduction of the NDIS, the Productivity Commission estimated there to be a 12,300 person supply gap. Since the approach was introduced, 817 new SDA places in 381 dwellings have been enrolled for use under the scheme (NDIS 2019).

Housing assistance policy framework

Government policies and funding provide support for people whether they are homeless, at risk of homelessness or need support to secure/sustain housing. The government is involved in housing assistance in three main areas: social housing services, financial assistance (private housing) and specialist homelessness services. Policies and programs operate at both national and state/territory levels.

The National Housing and Homelessness Agreement provides frameworks for all levels of government to work together into the future to improve housing affordability and homelessness outcomes for low and moderate income households (CFFR 2019).

National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA)

The National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA) commenced on 1 July 2018 to improve housing and homelessness outcomes for Australians. This Agreement between the Commonwealth and State and Territory governments replaced the National Affordable Housing Agreement (NAHA) and the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness (NPAH). The NHHA combines funding for these previous separate housing and homelessness agreements, with dedicated homelessness funding to be matched by States and Territories.

The bilateral schedules negotiated between the Commonwealth and each State and Territory are intended to reflect the mutual interest and shared responsibility in improving housing outcomes for Australians. They provide clear targets to help ensure that each state and territory is accountable for better outcomes that recognise their different housing markets as well as facilitating sector-wide performance monitoring (COA 2017). The NHHA focuses on specific priorities such as supply targets, planning and zoning reforms and renewal of public housing stock. It will also focus on supporting the delivery of frontline homelessness services and requires homelessness strategies to be developed for several national priority cohorts. Funding will be ongoing and indexed annually (DSS 2019).

The objective of the NHHA is to improve access to affordable, safe and sustainable housing across the housing spectrum from crisis housing to home ownership. The specific goals are to achieve:

- a well-functioning social housing system

- affordable housing options for those on low to moderate incomes

- an effective homelessness service system for those at risk of homelessness or homeless

- improved housing outcomes for Indigenous Australians

- a well-functioning housing market

- improved transparency and accountability for housing and homelessness strategies, spending and outcomes (CFFR 2019).

Housing assistance funding

In 2017–18, the Australian and State and Territory government total recurrent expenditure for social housing and specialist homelessness services was $5.0 billion. Of this, social housing-related costs accounted for $4.1 billion and $0.9 billion for specialist homelessness services. (SCRGSP 2019)

Social Impact Investment (SII)

Governments are also trialling new forms of investment approaches, including Social Impact Investment (SII), to drive improved responses to challenging social issues such as homelessness and housing. SIIs are those intended to generate measurable social and/or environmental benefits coupled with a financial return (Sharam et al 2018). The 2017–18 Australian Government budget included $30 million in funding over 10 years for SII initiatives (Treasury 2019).

The partnerships between private sector, non-government agencies and governments can generate new sources of funding, provide longer-term funding outlooks and, through outcome-based arrangements, offer flexibility in service delivery.

Glossary

References

- SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2019. Report on Government Services 2018 – Housing (Part G, Chapter 18). Viewed 4 April 2019.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2017a. Housing Occupancy and Costs, Australia, 2015–16. ABS cat. No. 4130.0, Canberra: ABS.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) 2017. Affordability Housing Database. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- ABS 2016. 2016 Census of Population and Housing, TableBuilder Pro. Findings based on use of ABS TableBuilder Pro data.

- ABS 2017b. 2071.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the Census, 2016, Jun. 2017. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2018. 2049.0 Census of Population and Housing: Estimating homelessness, 2016, Mar. 2018 Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2019. Residential property price indexes: eight capital cities, Dec. 2018. ABS cat. no. 6416.0. Canberra: ABS.

- Yates J 2007. Housing affordability and financial stress, NRV3 Research paper 6, Melbourne: AHURI.

- Commonwealth Senate Economic References Committee 2015. Out of reach? The Australian housing affordability challenge, Canberra.

- Stone W, Parkinson S, Sharam A and Ralston L 2016. Housing assistance need and provision in Australia: a household-based policy analysis. AHURI Final Report 262. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Stone W, Sharam A, Wiesel I, Ralston L, Markkanen S, & James A 2015. Accessing and sustaining private rental tenancies: critical life events, housing shocks and insurances. AHURI Final Report No.259. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- IBA (Indigenous Business Australia) 2019. Indigenous Home Ownership Program Policy. Canberra: IBA.

- NDIS 2019 COAG Disability Reform Council Quarterly Report 31 March 2019. Viewed 03 June 2019.

- SGS Economics and Planning 2018. Specialist disability accommodation: market insights. Viewed 12 December 2018.

- Council on Federal Financial Relations (CFFR) National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Viewed 23 January 2019.

- Sharam A, Moran M, Mason C, Stone W, & Findlay S 2018. Understanding opportunities for social impact investment in the development of affordable housing - Inquiry into social impact investment for housing and homelessness outcomes. DOI: 10.18408/ahuri-5310202. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Commonwealth Treasury website. Viewed 26 February 2019.