Wildlife and venomous animals

Wildlife

-

In 2021-22, wildlife (excluding marine animals) caused 4,980 injury hospitalisations (21%or 19.3 per 100,000)

-

2,394 (48%) were related to reptiles, 539 (11%) being venomous snakes or lizards

-

Insects and arthropods were associated with 1,504 (30%), including 474 (10%) from spiders

-

Males were injured more than females (24 and 15 per 100,000 respectively)

-

Homes were the most frequently recorded place of injury (1,009 cases, 20%)

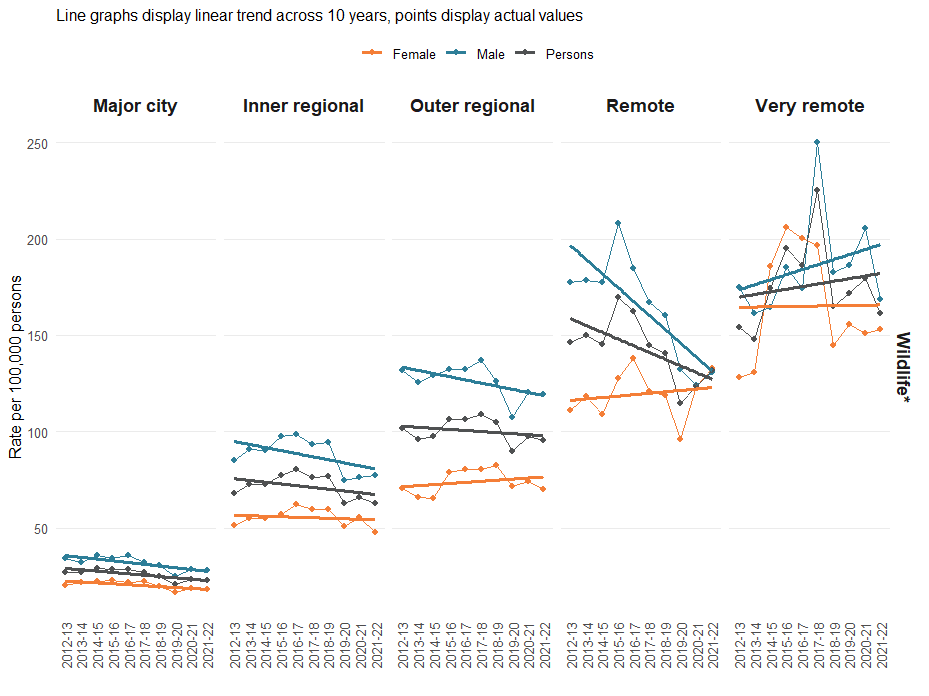

Wildlife-related injury hospitalisations have been decreasing since 2012 across all ages, and sexes and regions (Figure 15). Rates of these injuries are highest among males and in very remote regions (Table 4). Injuries frequently occur at home and during work activity (Figure 8). For more information, please refer to supplementary data table 3.

Figure 15: Crude rates of injury hospitalisations related to wildlife, by region, Australia, 2012-22

Notes:

* Excluding marine animals, including venomous wildlife

For each region, crude rates along the y-axis are calculated using the total estimated regional population as denominators.

Source: National Hospital Morbidity Database

Venomous animals

In 2021-22 venomous animals contributed to less than 1% of all cause injury hospitalisations across Australia. The number of injury hospitalisations due to venomous animals decreased to 2,867 in 2021-22 from 3,520 in 2017-18. Published research indicated 39,619 hospitalised injuries due to venomous animals over the 11 years between August 2001 and May 2013, an average of about 3,600 cases a year (Welton, Williams et al. 2017).

In 2021-22, the crude rate of injury hospitalisations due to venomous animals was 11.1 per 100,000, as compared to 72.8 per 100,000 for non-venomous animals. In 2017-18 this rate was 14.2 per 100,000 people (AIHW 2021). For more information, please refer to supplementary data tables 6 and 7.

Figure 16: The top 5 ranked causes of the 2,867 injury hospitalisations caused by venomous animals, 2021-22

-

Bee allergies caused 1,072 cases (4.1 per 100,00 or 37%). A further 201 cases were hospitalised due to contact with hornets, wasps or bees.

-

Venomous snakes and lizards caused 539 hospitalisations (201 per 100,000 or 19%). Brown snakes were most commonly identified (200 cases) while the snake was unspecified in 190 cases.

-

Spiders caused 455 injury hospitalisations (1.8 per 100,00 or 16%). Most were unspecified (277 cases), followed by redbacks (111 cases) and funnel web spiders (39 cases).

-

280 injury hospitalisations (1.1 per 10,000 or 10%) were due to venomous arthropods, the majority being ticks (116 cases) and venomous ants (84 cases).

-

121 hospitalisations were due to contact with jellyfish (0.5 per 100,000 or 4%) of which 91 were due to irukandji.

Of the 2,867 injuries from venomous animals, more than 60% of hospitalised cases were males (1,782 cases, 13.9 per 100,000). Most cases were adults with the highest rate being 14.4 per 100,000 among 45–64-year-olds. For more information, please refer to supplementary data table 6.

More than 50% of incidents (1,468 cases) did not have place of occurrence specified, but where it was, most venomous injuries occurred in homes (796 cases or 27%, of which 788 cases were caused by wildlife). Likewise, most incidents did not have a specific activity noted (2,041 cases or 71%) but where it was, work was the most frequent activity being undertaken during these incidents (414 cases or 14%). In two thirds of these cases (281 cases) the affected person was engaged in work that may not be associated with an income (for example, caring roles at home) (Figure 8). For more information, please refer to supplementary data table 8.

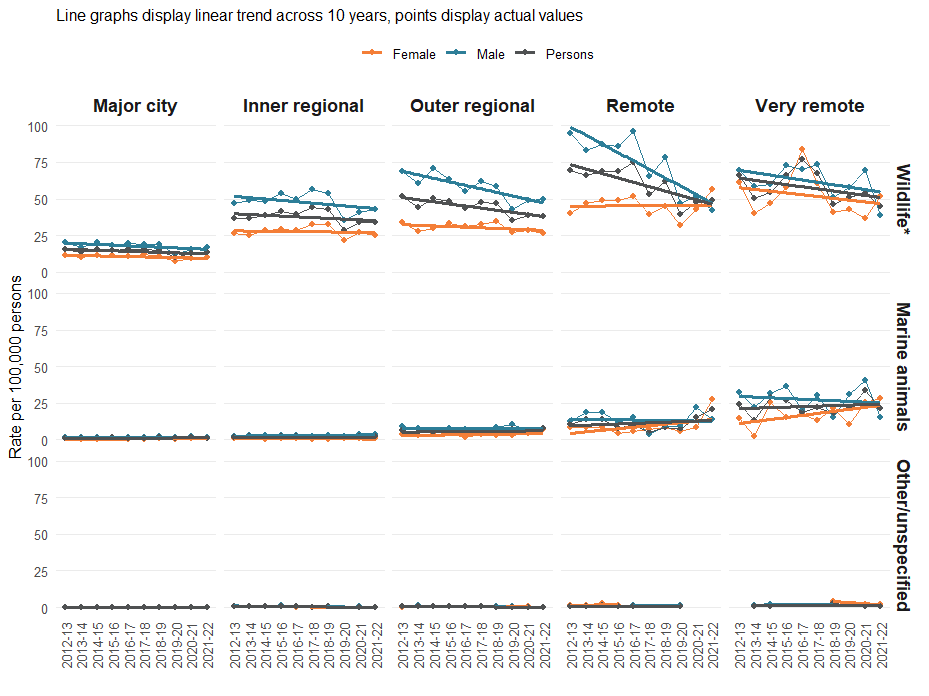

Trends

Injury hospitalisations associated with all venomous animals have remained relatively stable across Australia since 2012-13. 45–64-year-olds remain the most likely age group to be hospitalised for these injuries (Figure 17). Rates of hospitalisation increased with remoteness (Figure 18). Those associated with venomous wildlife have decreased across all age groups and regions (Figure 18). For more information, please refer to supplementary data table 2.

Figure 17: Heatmap of crude rate (per 100,000) of injury hospitalisations due to contact with venomous animals by age, Australia, 2012–13 to 2021–22

Source: National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 18: Venomous animal related rates of injury hospitalisations, by region and venomous animal type, Australia, 2012-22

Notes:

* Excluding marine animals. Wildlife here represents only venomous wildlife.

For each region, crude rates along the y-axis are calculated using the total estimated regional population as denominators.

Source: National Hospital Morbidity Database

Envenomation is described further under Types of injuries and Envenomation and antivenom.

Snake bite envenomation (where exposure to a poison or toxin is from an animal’s bite) is uncommon (Braitberg, Nimorakiotakis et al. 2021), with a total of 535 hospitalisations during 2021-22 of which 165 had a primary diagnosis of toxic effect of snake venom (T63.0) recorded. The relationship between cases, species and whether toxic effects of venom occur is complex, with the commonest species causing the most injuries having the lowest recorded proportions of hospitalisation due to toxic effects of venom (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Snake bite injury hospitalisations by species and whether a principal diagnosis of toxic effect of venom (T63.0) was recorded, 2021-22

Source: National Hospital Morbidity Database

For more information, please refer to supplementary data table 7.

Data from the Australian Snakebite Project 2005-2015 indicates nearly half of snake bites occurred when people were unknowingly active around a snake with a further 15% occurring when people attempt to catch or kill snakes (Johnston, Ryan et al. 2017).

AIHW (2021). Venomous bites and stings 2017–18. AIHW. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Braitberg, G., V. Nimorakiotakis, C. Y. L. Yap, V. Mukaro, R. Welton, A. Parker, J. Knott and D. Story (2021). "The Snake Study: Survey of National Attitudes and Knowledge in Envenomation." Toxins (Basel) 13(7).

Johnston, C. I., N. M. Ryan, C. B. Page, N. A. Buckley, S. G. Brown, M. A. O'Leary and G. K. Isbister (2017). 'The Australian Snakebite Project, 2005–2015 (ASP-20).' Medical Journal of Australia 207(3): 119-125.

Welton, R. E., D. J. Williams and D. Liew (2017). 'Injury trends from envenoming in Australia, 2000–2013.' Internal Medicine Journal 47(2): 170-176.