Department of Veterans’ Affairs clients

On this page:

Background

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) is responsible for developing and providing a range of services, programs of care, compensation, income support, and commemoration for the veteran and defence force communities and their families (DVA 2021a). Permanent, reserve and ex-serving ADF members may be eligible to receive a range of entitlements depending on personal circumstances, such as compensation payments, means-tested pensions, and subsidised health treatments.

DVA works with veterans and their families to improve services and support for those who have served in the ADF, and continues to play a part in improving mental health and wellbeing outcomes, and reducing the risk of suicide (DVA 2020). Historically, permanent, reserve and ex-serving ADF members who are DVA clients may have complex physical and mental health care needs leading them to require greater health service use compared with non–DVA clients. Changes and introduction of new DVA policy measures have worked to improve the services and supports available to veterans over time. For example, since mid-2018 permanent ADF members transitioning to civilian life are now issued a Veteran Card (White Card), which entitles them to treatment for all mental health conditions under the Non-Liability Health Care program.

This in-focus chapter presents a profile of the service-related characteristics of Australian Defence Force (ADF) members who have served between 1985 and 2021 and were DVA clients. Rates, numbers and proportions of deaths by suicide between 2002 and 2021 by DVA client status are also reported.

The analysis presented in this section uses data from the current DVA client and National Treatment Account system, and Department of Defence personnel systems. The analysis covers interactions with DVA by ADF members who have served at least one day since 1 January 1985, and who were alive or died between 2002 and 20211 .

Who are DVA clients?

In the general sense, DVA clients include permanent, reserve, or ex-serving ADF members, or their partners/dependants, who receive support from DVA. A DVA client can be a DVA card holder, a benefit or income recipient and/or a user of health or support services funded by DVA. DVA cardholders can access a range of benefits, including health care, pharmaceutical benefits and other concessions. There are several types of cards issued to DVA clients - the Veterans White Card is the most common. The Technical notes sections contain further discussion of DVA client status.

This analysis includes DVA clients who are permanent, reserve or ex-serving ADF members, with a focus on ex-serving ADF members. It does not include family members or dependents.

Permanent, reserve and ex-serving ADF members vary in how actively they engage with DVA for support, how much support they need, and the benefits to which they are eligible. This report considers 2 types of DVA client status, described in Box 3.

Box 3: Definitions of DVA client groups considered in this report

DVA client: Permanent, reserve, or ex-serving ADF members who have had any kind of interaction with DVA as an eligible client. This includes those who have:

- been issued a DVA card, made at least one claim accepted by DVA

- received any kind of payment from DVA

- accessed a DVA funded health or support service.

DVA recent interaction client: Permanent, reserve, or ex-serving ADF members who have received a DVA funded health or support service, or have received regular income or payments from DVA that would be considered a primary source of income, in the 2 years prior to a reference date or death. It is important to note that everyone occupying this category is also a broadly defined DVA client.

The broad definition of DVA client is inclusive of ADF members regardless of the date of contact with DVA, including where the only recorded accepted claim, card issue, benefit, payment or service occurred after death. For example, this definition includes cases where compensation payments are made after the death of the ADF member. The recent interaction definition of DVA client also includes a small number of cases where the only recorded service or payment has occurred after death.

The definition of DVA client used in this report does not include ADF members whose only interaction with DVA was to make one or more claims that have not been accepted. This is to avoid situations where an individual is reported as a DVA client but has not been determined by DVA as eligible for any support or benefits. The number of ADF members over time who have only made claims that have not been accepted can be found in Supplementary tables S9.1 and S9.2. Note that the rate of suicide for ADF members who have only made claims that have not been accepted is not reported here due to the low numbers of deaths by suicide (Supplementary table S9.3).

Demographic characteristics of DVA clients

Between 2002 and 2021, 113,000 ex-serving ADF members who had served at least one day since 1985 were DVA clients (40% of the full ex-serving cohort). This includes both alive and deceased ADF members. Most, 98,000, were males (41% of all ex-serving males) and 14,600 were females (33% of all ex-serving females) 2.

At 31 December 2021, 57,500 male and 13,000 female DVA clients were currently permanent or reserve ADF members, representing around 71% of the permanent and reserve population in 2021. Data for this cohort are in Supplementary tables S9.2 and S9.3, however, the focus of the following analyses is on ex-serving DVA clients.

Supplementary tables S9.4 and S9.6 outline the demographics of the ex-serving DVA client cohorts. Some highlights are presented here.

Among ex-serving members who were alive or had died between 2002 and 2021 and were DVA clients:

- males were on average slightly older (mean age of 54) than the overall ex-serving male cohort (mean age of 52)

- females were on average slightly younger (mean age of 47) than the overall ex-serving female cohort (mean age of 49)

- males and females on average had a longer length of service (17 years for males and 11 years for females) than the overall ex-serving male and female populations (11 years for males and 8 years for females)

- males and females on average had been separated from the ADF for a shorter time (17 years for males and 15 years for females) than the overall ex-serving male and female populations (20 years for both males and females).

At 31 December 2021, of those who separated from 1 January 2003 3:

- 93% of males and 92% of females who separated for involuntary medical reasons were DVA clients

- 40% of males and 34% of females who separated for voluntary reasons were DVA clients

- 41% of males and 34% of females who separated for other involuntary reasons were DVA clients.

This report identifies the involuntary medical separation group as having a higher rate of suicide. The high proportion of ex-serving members who had accessed DVA services among those who separated for involuntary medical reasons may suggest that this cohort are aware of DVA entitlements and choose to access support as a DVA client. In contrast, among those who have separated for voluntary reasons, a cohort who have lower rates of suicide comparatively, a lower proportion were DVA clients. Among those who separated for other involuntary reasons, identified as having a higher rate of suicide, there is also a comparatively lower proportion of DVA clients 4.

Analysis by time since separation demonstrates changes in the proportions of DVA clients over time. As at 31 December 2021, of ex-serving members who were alive or had died and separated

- less than 1 year ago, 71% of males and 74% of females were DVA clients.

- between 1 and <5 years ago, 66% of males and 65% of females were DVA clients.

- between 5 and <10 years ago, 51% of males and 46% of females were DVA clients.

- between 10 and <20 years ago, 41% of males and 35% of females were DVA clients.

- 20 or more years ago, 33% of males and 22% of females were DVA clients.

This suggests that those who have separated in more recent times are more readily interacting with DVA, which is indicative of changes in policies and eligibility over time, as discussed in the following section.

Trends in DVA clients over time

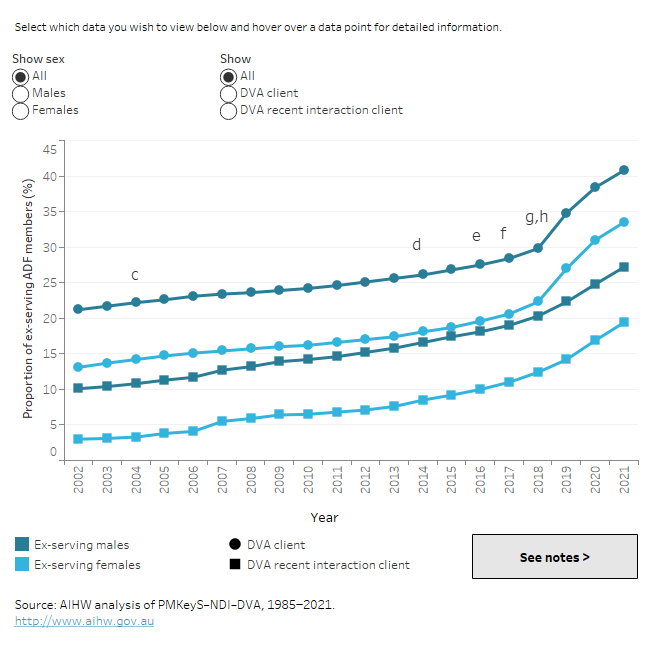

The proportion of ex-serving ADF members who were DVA clients increased between 2002 and 2021 (see Figure 17) from:

- 21% in 2002 to 41% in 2021 among males

- 13% in 2002 to 34% in 2021 among females

The proportion of ex-serving ADF members who were recent interaction clients increased between 2002 and 2021 as follows:

- 10% in 2002 to 27% in 2021 for males

- 3.0% in 2002 to 19% in 2021 for females

The increase in proportion of ex-serving ADF members who are DVA clients is largely due to the introduction of new programs and policy reforms that focus on the health and well-being of veterans. These have included changes to Non-Liability Health Care (NLHC) arrangement in July 2017, to provide eligible veterans with access to fully funded treatment of all mental health conditions without the need to prove that ADF service caused the conditions. Previously NLHC had been limited to select mental health conditions (see Technical notes for further information).

Figure 17: Percentage of ex-serving males and females who were a DVA client or recent interaction DVA client by sex 2002 to 2021(a)

This time series line graph shows the yearly proportions of ex-serving males and females who were a DVA client or recent interaction DVA client over time from 2002 to 2021.

The proportion of ex-serving ADF members who had only made claims that had not been accepted by DVA decreased from 2.2% in 2002 to 1.2% in 2021 among males and from 1.7% in 2002 to 1.2% in 2021 among females.

The proportion of ex-serving ADF members who had served at least one day since 1985, who were cardholders has increased since 20025:

- Veteran White Card holders rose from 11% to 27% in 2021 for ex-serving males and 4.6% to 25% for ex-serving females

- Veteran Gold Card holders rose from 4.3% to 11% in 2021 for ex-serving males, and from 0.7% to 3.8% for ex-serving females

Among ADF members who were permanent or reserve at 31 December 2021, 67% of females and males had a Veteran White Card, and 1.3% of females and males had a Veteran Gold Card.

The proportion of ex-serving ADF members who were Veteran Orange Card holders is not presented due to small numbers (see Supplementary table S9.1). For more information and definitions of the DVA client cardholder types, see Technical notes.

DVA clients who died by suicide

This section presents suicide rates, numbers and proportions of deaths by suicide between 2002 and 2021 broken down by the DVA client status (DVA client and DVA recent interaction client).

It is important to note that ADF members who are eligible for DVA support – and who access services funded by DVA – are more likely to have physical and mental health needs that would have led them to DVA. In particular, at 31 December 2021, 93% of the involuntary medical separation cohort was a DVA client compared with 39% of the voluntary separation cohort. The key findings of this report show that the involuntary medical separation group have a higher rate of suicide. These data importantly suggest that DVA support is appropriately provided to this group.

The number and proportion of DVA clients who died by suicide can be found in Table 11. While reading these data it should be remembered that, for the purposes of this report, all recent interaction clients are also part of the DVA client group.

DVA client category | Number of males who died by suicide | % of ex-serving ADF males who died by suicide | Number of females who died by suicide | % of ex-serving ADF females who died by suicide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

DVA client(b) | 306 | 29.1% | 25 | 24.8% |

DVA recent interaction client(c) | 197 | 18.7% | 16 | 15.8% |

Non-DVA client | 747 | 70.9% | 76 | 75.2% |

Total suicides | 1,053 | 100% | 101 | 100% |

Notes

a. Note that the Total suicides numbers do not agree with Table 1 because this count runs from 2002-2021 rather than 1997-2021.

b. Includes ex-serving members who met one of the following conditions: had a White or Gold card or received a health service or support service (National Treatment Account or MBS or Hospital separation or ED attendance) or received an income or other payment or had at least one accepted claim. See Technical notes: DVA client definitions for more information.

c. Includes ex-serving members who met one of the following conditions: received a health service or support service through DVA (National Treatment Account or MBS or Hospital separation or Emergency Department (ED) attendance) or received an income payment from DVA in the past 2 years. See Technical notes: DVA client definitions for more information.

Source: AIHW analysis of PMKeyS–NDI–DVA, 1985−2021.

Among permanent and reserve male ADF members who died by suicide, 41% were DVA clients. Among permanent and reserve male ADF members who died by suicide, 16% were recent interaction clients indicating they were in receipt of DVA funded health care or income support in the two years prior to death. DVA clients and recent interaction clients include cases where interactions only occurred after death, for example where compensation has been provided after the death of an ADF member.

Among a small proportion of ADF members who died by suicide, the only interaction recorded with DVA was claims that had not been accepted – 3.9% of permanent and reserve ADF males who died by suicide had only made claims that had not been accepted, and 3.4% of ex-serving ADF males who died by suicide had only made claims that had not been accepted. Non-liability health care and other services such as employment support may still be provided to ADF members without accepted claims.

Of the ADF members who died by suicide between 2003 and 20216,

- 65 were males who separated for involuntary medical reasons and were also DVA clients (81% of all suicide deaths among males who separated for involuntary medical reasons)

- 32 were males who separated for other involuntary reasons and were also DVA clients (29% of all suicide deaths among males who separated for other involuntary reasons)

- 25 were males who separated voluntarily and were also DVA clients (30% of all suicide deaths among males who separated voluntarily).

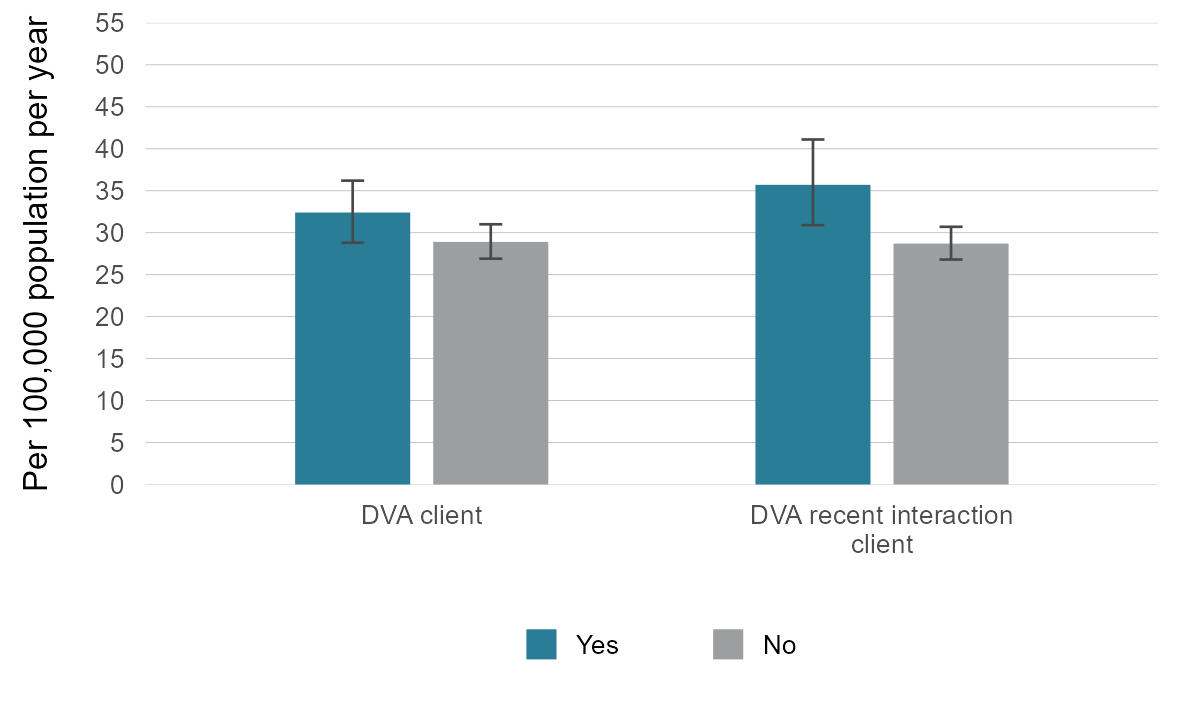

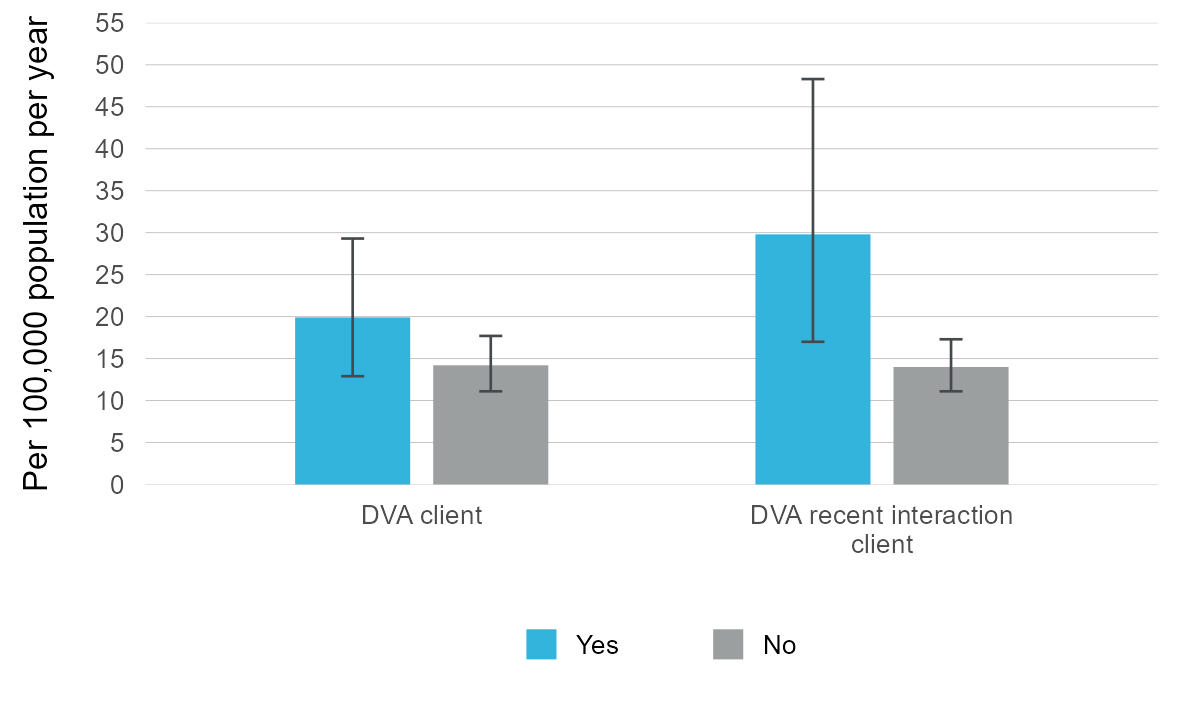

The suicide rates for the DVA client groups and all other ex-serving members are in Table 12 below. As Figures 18 and 19 show, none of these differences are statistically significant, and do not demonstrate a difference between the two groups, largely due to low numbers especially among the female ex-serving cohort.

DVA client category | Ex-serving males: Suicide rate per 100,000 population per year | Ex-serving females: Suicide rate per 100,000 population per year |

|---|---|---|

DVA client |

|

|

Yes | 32.4 | 19.9 |

No(a) | 28.9 | 14.2 |

DVA recent-interaction client |

|

|

Yes | 35.7 | 29.8* |

No(b) | 28.7 | 14.0 |

a. This group is composed of every member of the ex-serving cohort that is not a DVA client.

b. This group is composed of every member of the ex-serving cohort that is not a DVA recent interaction client. DVA clients with no recent interaction are a part of this group.

* Suicide rates in this Table denoted with a '*' should be interpreted with caution as the number of suicides is fewer than 20. These rates are considered potentially volatile.

Source: AIHW analysis of PMKeyS–NDI–DVA, 1985−2021.

Figure 18: Rate of suicide among ex-serving males who were DVA clients and non-DVA clients, 2002 to 2021

Notes:

a. DVA recent interaction clients are a subset of DVA clients. Therefore, comparisons for statistical significance of the suicide rate between DVA clients and DVA recent interaction clients should not be made.

b. Ex-serving members who are non-DVA recent interaction clients include those who are not DVA clients and DVA clients who are not DVA recent interaction clients.

c. This Figure shows that the differences in the rate of suicide between DVA clients and non DVA clients, and between DVA recent interaction clients and non DVA recent interaction clients, were not statistically significant.

Source: AIHW analysis of PMKeyS–NDI–DVA, 1985−2021.

Figure 19: Rate of suicide among ex-serving females who were DVA clients and non-DVA clients, 2002 to 2021

Notes:

a. DVA recent interaction clients are a subset of DVA clients. Therefore, comparisons for statistical significance of the suicide rate between DVA clients and DVA recent interaction clients should not be made.

b. Ex-serving members who are non-DVA recent interaction clients include those who are not DVA clients and DVA clients who are not DVA recent interaction clients.

c. This Figure shows that the differences in the rate of suicide between DVA clients and non DVA clients, and between DVA recent interaction clients and non DVA recent interaction clients, were not statistically significant.

Source: AIHW analysis of PMKeyS–NDI–DVA, 1985−2021.

Data underlying this section are available in Supplementary tables S9.8 and S9.9. These Tables include suicide rates among ex-serving ADF members by DVA client status and service-related characteristics including separation reason.

Continued research into the 2 DVA client groups, incorporating additional factors such as health conditions related to claims made to DVA, may provide further insight into the health and wellbeing outcomes for ex-serving ADF members.

Help or support

If you need help or support, please contact:

- Open Arms – Veterans and Families Counselling – Phone: 1800 011 046

- Open Arms Suicide Intervention

- Defence All-hours Support Line (ASL) – Phone: 1800 628 036

- Defence Member and Family Helpline – Phone: 1800 624 608

- Defence Chaplaincy Support

- ADF Mental Health Services

- Lifeline – Phone: 13 11 14

- Suicide Call Back Service – Phone: 1300 659 467

- Beyond Blue Support Service – Phone: 1300 22 4636

For information on support provided by DVA, see:

- As this analysis relies on Defence personnel data, it covers interactions with DVA by ADF members who have served at least one day since 1 January 1985, it does not include ex-serving ADF members who separated from the ADF prior to 1985. For example, the analysis does not include DVA clients who served in the Vietnam War, Korean War and World War II, and who separated from the ADF prior before 1985.

- Note, as this analysis covers interactions with DVA by ex-serving ADF members who have served at least one day since 1 January 1985, it does not include the cohort of DVA clients who served in the Vietnam War, Korean War and World War II, and who separated from the ADF prior to 1985.

- Due to a change in the way the reason for separating from the ADF was recorded in 2002, analysis by reason for separation is only reported for ADF members who separated from 1 January 2003 onwards. These members comprise 43% of the ex-serving cohort.

- The lower proportion of DVA clients among those separating voluntarily or due to other involuntary reasons may be indicative of historical eligibility requirements for DVA support, in particular prior to recent policy changes which entitle all ADF members transitioning from permanent service to receive a Veteran White Card.

- It is important to note that this analysis covers interactions with DVA by ex-serving ADF members who have served at least one day since 1 January 1985, it does not include the ex-serving cohort who separated from the ADF prior to 1985 and may also hold Veteran cards. Due to the scope of data included, these Figures may differ from Figures published by DVA or AIHW which include ex-serving ADF members who separated prior to 1985 and/or dependents.

- Due to a change in the way the reason for separating from the ADF was recorded in 2002, analysis by reason for separation is only reported for ADF members who separated from 1 January 2003 onwards. These members comprise 43% of the ex-serving cohort.