Detention

On an average day in 2022–23, 18% (828) of young people aged 10 and over who were under youth justice supervision were in detention. Almost 2 in 3 (483, or 58%) of whom were First Nations young people (Table S73a).

Of all young people in detention on an average day aged 10 and over, almost 4 in 5 were unsentenced (80%) and 1 in 4 (25%) were in sentenced detention.

A total of 4,605 young people were in detention at some time during the year (Table S108).

In 2022–23, the rate of First Nations young people aged 10–17 in detention on an average day was 30 per 10,000, compared with 1.1 per 10,000 for non-Indigenous young people (Table S75a). This means First Nations young people aged 10–17 were about 28 times as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to be in detention on an average day.

This level of First Nations over-representation (as measured by the rate ratio – see Appendix A) was higher for those in detention than for those under community-based supervision (about 22 times as likely) (Table 3.1). In this section proportions should be interpreted with caution, especially in the smaller jurisdictions as they may represent a very small number of young people.

Unsentenced detention

As with community-based supervision, young people may be detained when they are unsentenced or sentenced. Some young people may also be in unsentenced and sentenced detention on the same day. This can occur when the young person has changed legal status or has both types of legal orders at the same time for different legal matters.

Number and rate

Young people may be referred to unsentenced detention either by the police (pre-court) or by a court (remand). Young people enter remand when they have been either:

- charged with an offence and are awaiting the outcome of their court matter

- found guilty, or have pleaded guilty, and are awaiting sentencing.

Young people enter police-referred pre-court detention before their initial court appearance. Police-referred pre-court detention is not available in all states and territories and most young people in unsentenced detention are on remand.

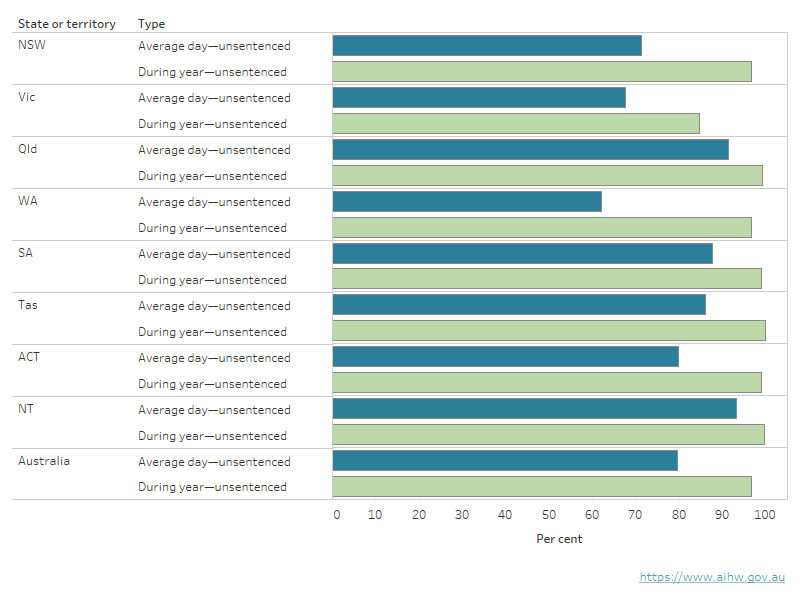

On an average day in 2022–23, of all young people in detention aged 10 and over, 4 in 5 were unsentenced (80%) (Figure 5.1). In all states and territories, a substantial proportion of those in detention on an average day were unsentenced – ranging from 62% in Western Australia to 93% in the Northern Territory.

The low proportion in Victoria (68%) is due, in part, to the state’s ‘dual track’ sentencing system, which allows some young people aged 18–20 to be sentenced to detention in a youth facility rather than in an adult prison if the young person is particularly impressionable, immature or likely to be subject to undesirable influences in an adult prison. When only young people aged 10–17 are considered, a similar proportion of those in detention in Victoria and nationally on an average day were unsentenced (88% and 85%, respectively) (Table S109a).

More than 9 in every 10 (97%) young people who were in detention during 2022–23 had been in unsentenced detention at some time during the year (Figure 5.1). This highlights the typically shorter duration of periods of unsentenced detention compared with sentenced detention.

On an average day in 2022–23, more than 4 in 5 (83%) First Nations young people in detention aged 10 and over were unsentenced. For non-Indigenous young people, this proportion was about 3 in 4 (76%). A similar proportion of First Nations and non-Indigenous young people had been in unsentenced detention at some point during the year (98% and 95%, respectively).

Figure 5.1: Young people aged 10 and over in unsentenced detention on an average day and during the year as a proportion of all young people in detention, by State or territory, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart shows that the Northern Territory (93%) had the highest proportion of unsentenced young people on an average day, while Western Australia (62%) had the lowest. During the year, Tasmania and the Northern Territory had the highest proportion of unsentenced young people (both 100%), while Victoria (85%) had the lowest.

Notes

- Numerators are the number of young people in unsentenced detention on an average day or during the year for each state and territory. Denominators are the total number of young people in detention on an average day or during the year for each state and territory.

- In the Northern Territory, sentenced periods were backdated to take into account time spent in unsentenced detention. This resulted in a large number of young people reported as being in sentenced and unsentenced detention at the same time and an over-count of young people in sentenced detention.

Sources: tables S108a and S108b.

Nationally, on an average day in 2022–23, most (98%) young people aged 10 and over in unsentenced detention were on remand, awaiting the outcome of their court matters (Table S108a). The remainder were in police-referred pre-court detention (see Glossary) awaiting their initial court appearance, which was available in some jurisdictions (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory).

In those states and territories where the data were available, the proportion of young people in police-referred pre-court detention ranged from 20% of those who had been in unsentenced detention during the year in Queensland to 93% of those in the Australian Capital Territory (Table S108b).

Almost 3 in 5 (60%) young people in unsentenced detention aged 10 and over on an average day identified as being First Nations people (Table S108a). This proportion varied substantially among the states and territories, from 13% in Victoria to 95% in the Northern Territory.

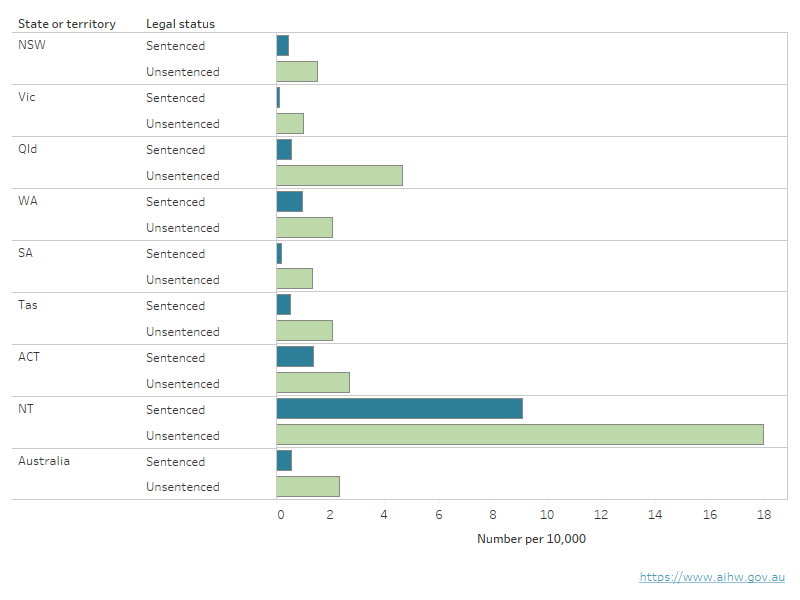

The rate of young people aged 10–17 in unsentenced detention on an average day in 2022–23 was 2.3 per 10,000 (Figure 5.2). Among the states and territories, this rate was lowest in Victoria (1.0 per 10,000) and highest in the Northern Territory (18 per 10,000).

Rates of unsentenced detention on an average day were higher than sentenced detention in all states and territories.

Figure 5.2: Young people aged 10–17 in detention on an average day, by legal status and State or territory, 2022–23 (rate)

This horizontal bar chart shows the rate of young people in unsentenced detention was higher than the rate of those in sentenced detention in every state and territory. The rates of young people aged 10–17 in sentenced and unsentenced detention on an average day were highest in the Northern Territory (9.1 and 18 per 10,000, respectively) and lowest in Victoria (0.1 and 1.0 per 10,000, respectively).

Notes

- The sentenced rates in South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory are not presented in this figure, as there were fewer than 5 young people in the numerator.

- In the Northern Territory, sentenced periods were backdated to take into account time spent in unsentenced detention. This resulted in a large number of young people reported as being in sentenced and unsentenced detention at the same time and an over-count of young people in sentenced detention.

- Age on an average day is calculated based on the age a young person is each day that they are under supervision. If the age of a young person changes during a period of supervision, the average daily number under supervision will reflect this. Average daily data broken down by age will not be comparable with data in Youth justice in Australia releases before 2019–20.

Source: Table S110a.

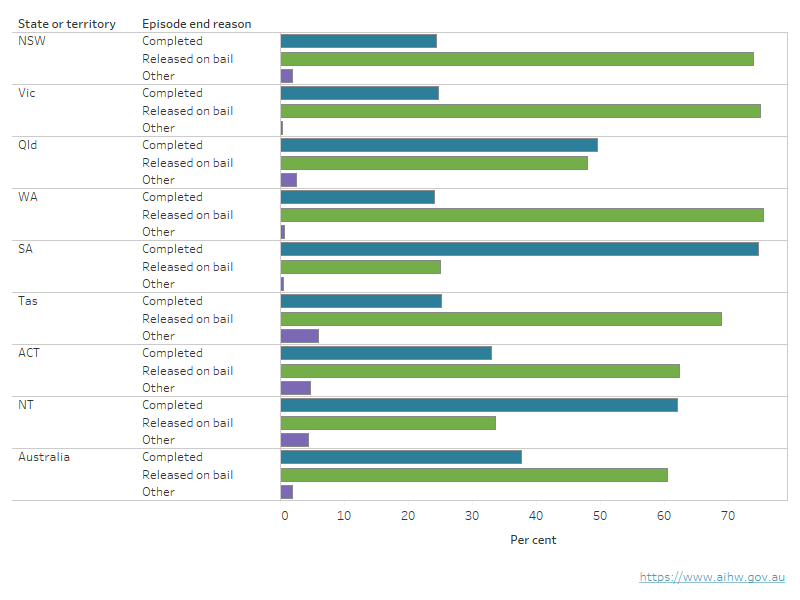

Completion of periods

Of remand periods (unsentenced detention) that ended in 2022–23, 3 in 5 (60%) ended because the young person was released on bail (Figure 5.3). This proportion was lower for First Nations young people than non-Indigenous young people (57% and 67%, respectively).

The proportion of remand periods that ended with release on bail was lowest in South Australia (25%) and highest in Victoria and Western Australia (75%) (Table S118).

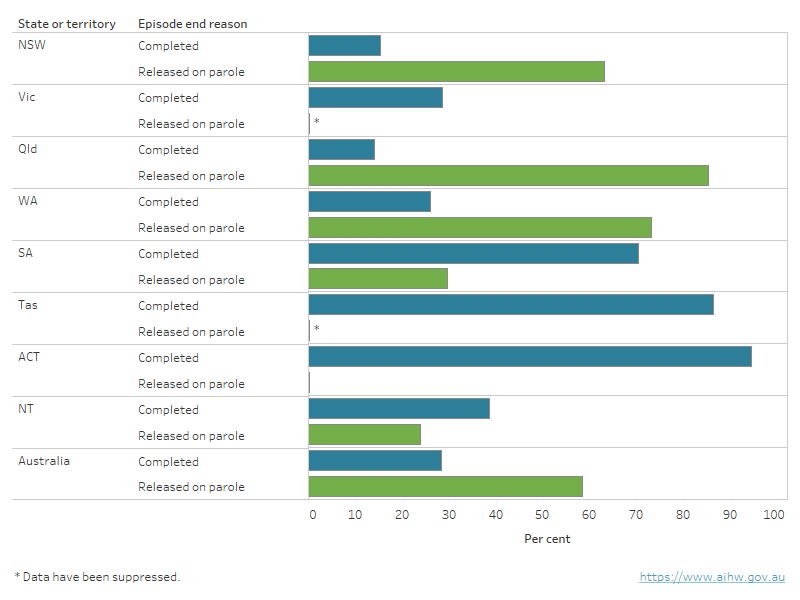

Figure 5.3: Periods of remand, by episode end reason and State or territory, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart shows that periods of remand were more likely to end because a young person was released on bail across all jurisdictions except for Queensland, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. In these states and territories, young people were most likely to end a period of remand because it was completed.

Notes

- These data should be interpreted with caution due to potential issues with recording and updating of custodial order details in Tasmania.

- Periods of remand may be slightly understated for Tasmania for 2022–23.

Source: Table S118.

Almost 2 in 5 (38%) remand (see Glossary) periods ended because they were completed. This episode end reason was higher for First Nations young people than non-Indigenous young people (41% and 32%, respectively). The remaining periods ended for other reasons, including transfer (which can include transfer to another youth detention centre, the adult system or interstate).

Sentenced detention

Young people may be sentenced to detention if they are judged to be guilty, or have pleaded guilty, in court. Young people sentenced to detention are those who have received control orders or youth residential orders or who have had their parole revoked (which can be due to re‑offending or non-compliance with parole conditions).

Number and rate

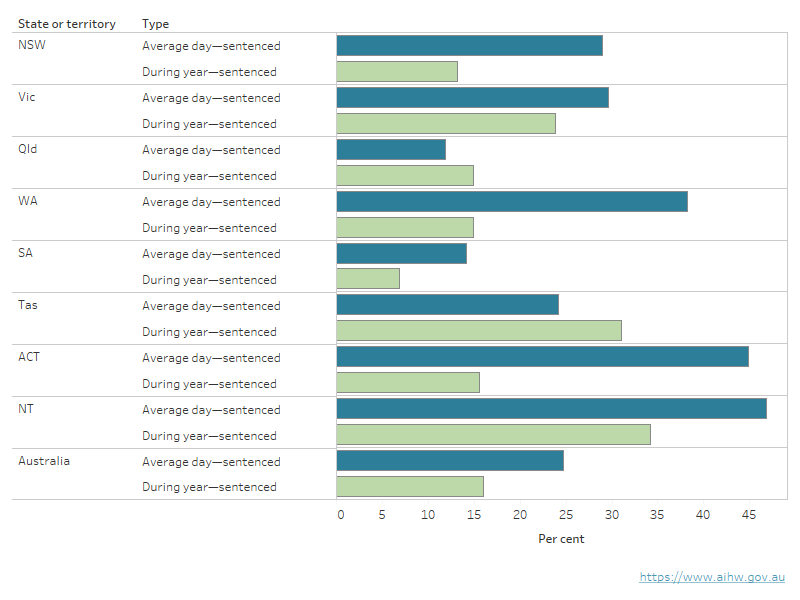

On an average day in 2022–23, 1 in 4 young people in detention (25%) were in sentenced detention (Figure 5.4). Among the states and territories, this ranged from 12% in Queensland to 47% in the Northern Territory.

Figure 5.4: Young people aged 10 and over in sentenced detention on an average day and during the year as a proportion of all young people in detention, by State or territory, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart shows that the highest proportion of all young people in detention on an average day that were sentenced occurred in the Northern Territory (47%) and Queensland (12%) had the lowest proportion.

Notes

- Numerators are the number of young people in sentenced detention on an average day or during the year by state and territory. Denominators are the number of young people in detention on an average day or during the year by state and territory.

- In the Northern Territory, sentenced periods were backdated to take into account time spent in unsentenced detention. This resulted in a large number of young people reported as being in sentenced and unsentenced detention at the same time and an over-count of young people in sentenced detention.

Source: Table S108.

Nationally, over half (57%) of all young people in sentenced detention on an average day identified as being First Nations (Table S108a). This proportion varied considerably among the states and territories.

On an average day in 2022–23, the rate of young people aged 10–17 in sentenced detention was 0.5 per 10,000 (Table S110a). Among the states and territories for which rates could be calculated, rates were lowest in Victoria (0.1 per 10,000) and highest in the Northern Territory (9.1 per 10,000).

Completion of periods

Nearly two-thirds (58%) of sentenced detention periods that ended in 2022–23 ended because the young person was released on parole (also known as supervised release). This was similar for First Nations young people and for non-Indigenous young people (60% and 58%, respectively).

Just over 1 in 5 (28%) sentenced detention periods ended with the period being completed (see Glossary). This was similar for First Nations young people and for non-Indigenous young people (27% and 29%, respectively).

The remaining periods (13%) ended for other reasons, including transfer (which can include transfer to another youth detention centre, the adult system or interstate).

The states and territories varied:

- In New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia, more than half (63–85%) of sentenced detention periods ended with the young person being released on parole.

- In South Australia, 30% of sentenced detention periods ended with the young person being released on parole, with the majority (70%) ending with the period being completed (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5: Sentenced detention ending with either sentence completion or release on parole (supervised release), by State or territory, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart shows that Queensland (85%) had the highest proportion of sentenced detention periods ending due to release on parole. The Australian Capital Territory (94%) had the highest proportion of young people ending their sentenced detention due to completion of sentence.

Notes

- Numerators are the number of sentenced detention periods that were completed or ended because the young person was released on parole, by state and territory.

- Denominators are the number of periods of sentenced detention, by state and territory. In some states and territories, a minimum duration of sentenced detention applies before a young person may be considered eligible for supervised release or parole. This affects the results and comparability.

- These data should be interpreted with caution due to potential issues with recording and updating of custodial order details in Tasmania.

- Periods of sentenced detention may be slightly understated for Tasmania for 2022–23.

Source: Table S123.

Detention entries and exits

In this report:

- a ‘reception’ is when a young person enters detention (either sentenced or unsentenced), having not been detained immediately before

- a ‘release’ is when a young person leaves detention and is not detained immediately afterwards.

To account for young people transported to court who return to detention after their court hearing, and young people transferred between detention centres, the start of a detention period is considered a reception only when it starts at least 2 full days after the end of the previous detention period.

Similarly, the end of a detention period is considered a release only when it ends at least 2 full days before the start of the next detention period. A change in legal status – for example, from unsentenced to sentenced detention within 2 days – is not counted as a new reception.

A release from detention comprises young people who have either been released to community-based supervision (such as on parole or supervised release) or left youth justice supervision altogether (on sentence completion).

There may be a small number of young people who are counted as having a reception or release if their travel time is longer than 2 full days when travelling to and from remote locations.

Receptions

In 2022–23, 4,265 young people experienced 8,965 receptions into detention (tables S103a and S103b). Among all young people in detention in 2022–23, 93% were received at some point during the year, with an average of about 2 receptions per young person, reflecting the short durations of detention periods. The rest were received in a previous year (tables S72b and S103b).

Almost half (48%) of young people who were received into detention during the year were received more than once (Table S105). First Nations young people (54%) were more likely than non-Indigenous young people (42%) to have been received into detention more than once.

Most receptions (98%) were for young people entering unsentenced detention, which consists of police-referred pre-court detention and remand (Table S103a).

Two-thirds of receptions (70%) were for remand, just under one-third (28%) were for police‑referred pre-court detention and 1.6% were for sentenced detention.

Nearly 1 in 5 (17%) young people in sentenced detention during 2022–23 were received during the year (tables S103b and S108b). This indicates that the rest were either received into sentenced detention in a previous year, or were in unsentenced detention immediately before they began their period of sentenced detention (and their sentenced period started within 2 days of their non-sentenced period ending).

Releases

In 2022–23, 4,417 young people experienced 9,066 releases from detention. The vast majority of young people (96%) who were detained during the year were released at least once, with an average of 2 releases per young person (tables S72b, S104a and S104b). Similar to receptions, 92% of releases were from unsentenced detention. About 3 in 4 releases (74%) were from remand and 18% were from police-referred pre-court detention. The proportion of releases from sentenced detention (8.1%) was higher than the proportion of receptions to sentenced detention (1.6%) (tables S103a and S104a).

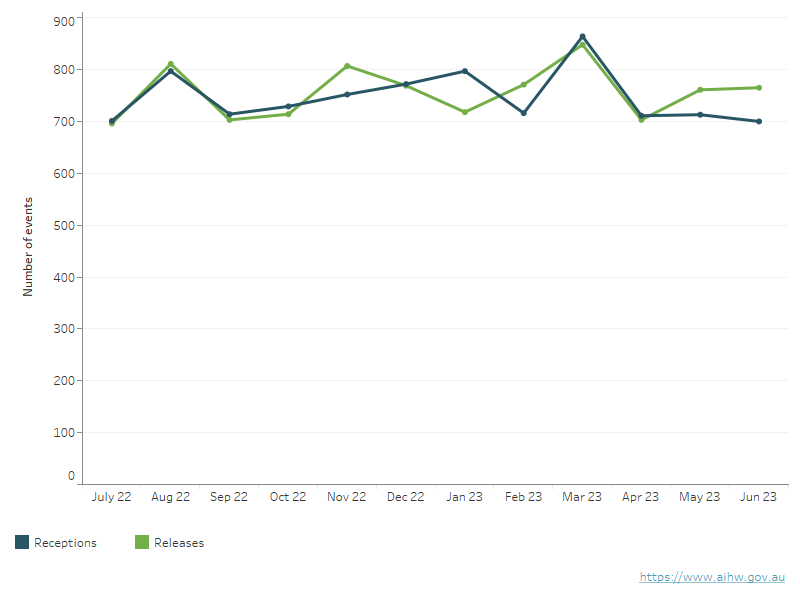

In 2022–23, the numbers of receptions and releases were closely aligned each month, despite some fluctuations (Figure 5.6. The highest number of receptions (864) and the highest number for releases (848) occurred in March 2023.

Figure 5.6: Monthly trends in youth detention receptions and releases, Australia, 2022–23

This line graph shows the monthly number of detention receptions and releases throughout the course of the year. For receptions, the monthly number fluctuated between 700 and 864 with a peak in March 2023 and a low in June 2023. Releases ranged from 696 to 848 with a high point in March 2023 and a low point in July 2022.

Source: Table S107.