Youth justice in context

Youth and adult justice systems in Australia

Contact with police

People first enter the justice system when they are investigated by police for allegedly committing an offence. Police may start legal action against them (proceed against) via court actions or non-court actions. Court actions are those where charges are laid that must be answered in court; non-court actions include cautions, conferences, counselling or infringement notices.

Young people are more likely than adults to be proceeded against for allegedly committing an offence. This is due, in part, to the fact that involvement in crime tends to be highest in adolescence or early adulthood and diminishes with age (Farrington 1986; Rocque et al. 2015; Ulmer and Steffensmeier 2014).

In 2022–23, police proceeded against 185 per 10,000 young people aged 10–17 (the primary group in the youth justice system) and 146 per 10,000 among those aged 18 and over (ABS 2024a).

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) publishes information on the types of principal (most serious) offences among young people who were proceeded against by police.

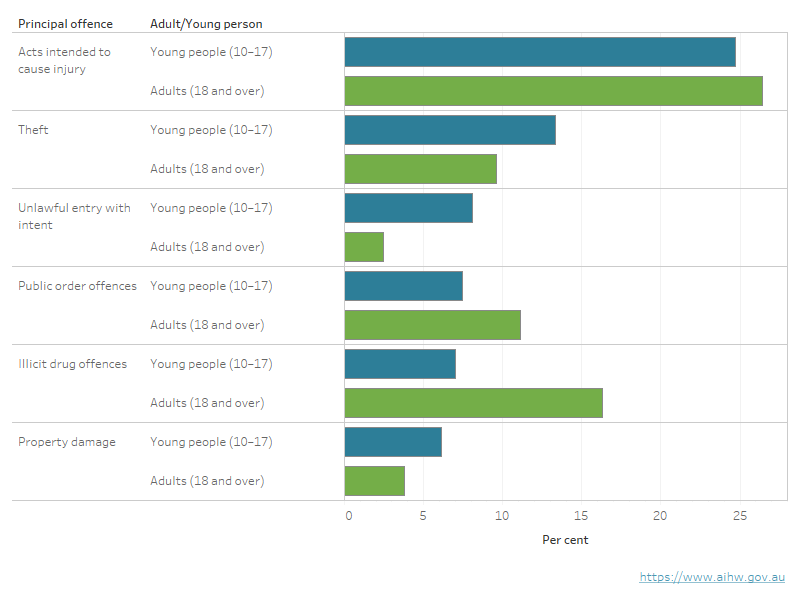

In 2022–23, the most common principal offences among young people aged 10–17 were:

- acts intended to cause injury (25%)

- theft (13%)

- unlawful entry with intent (8.1%) (Figure 9.1).

The most common principal offences among adults aged 18 and over were:

- acts intended to cause injury (26%)

- illicit drug offences (16%)

- public order offences (11%)

The adult category includes a much broader age group than the young people category and this might influence the results.

Figure 9.1: Young people and adults proceeded against by police, by selected principal offence, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart compares the principal offence committed, or alleged to have committed, by young people and adults. Acts intended to cause injury and theft were the most common principal offences for young people. For adults, acts intended to cause injury and illicit drug offences were the most common.

Source: ABS 2024a.

Community-based supervision, detention and prison

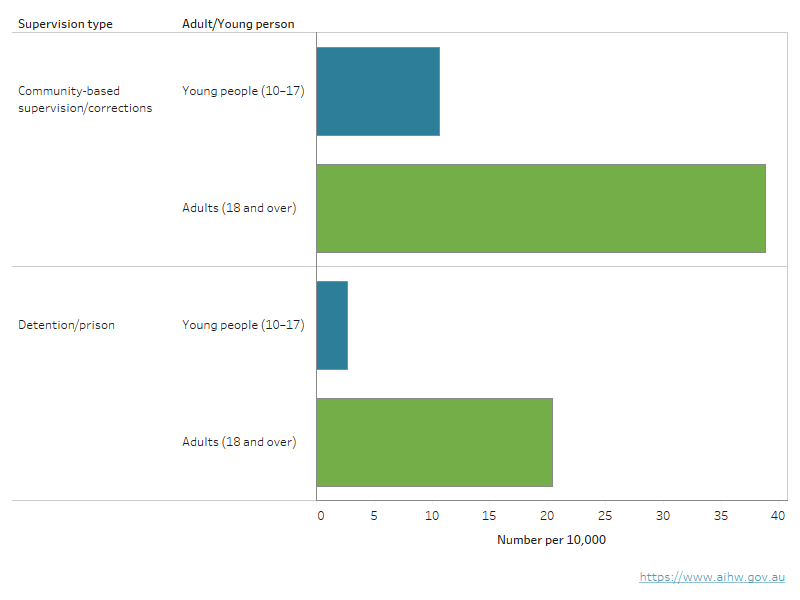

Although young people were more likely than adults to be proceeded against by police, adults were more likely to be placed under formal supervision.

On an average day in 2022–23, 39 per 10,000 adults aged 18 and over were in adult community-based corrections (Figure 9.2).

This compares with 11 per 10,000 young people aged 10–17 under community-based youth justice supervision on an average day in 2022–23.

At the same time, 20 per 10,000 adults were in prison compared with 2.7 per 10,000 young people aged 10–17 in youth justice detention (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2: Young people aged 10–17 and adults under supervision on an average day, by type of supervision, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart compares the rate of young people aged 10–17 and adults by supervision type. The rate of adults is considerably higher than young people in both community-based supervision/corrections and detention/prison.

Note: Data on young people under supervision are for 2022–23; available ABS data on adults under supervision are the average of monthly snapshots taken on the first day of the month from July 2022 to June 2023.

Sources: ABS 2023; tables S37a and S75a.

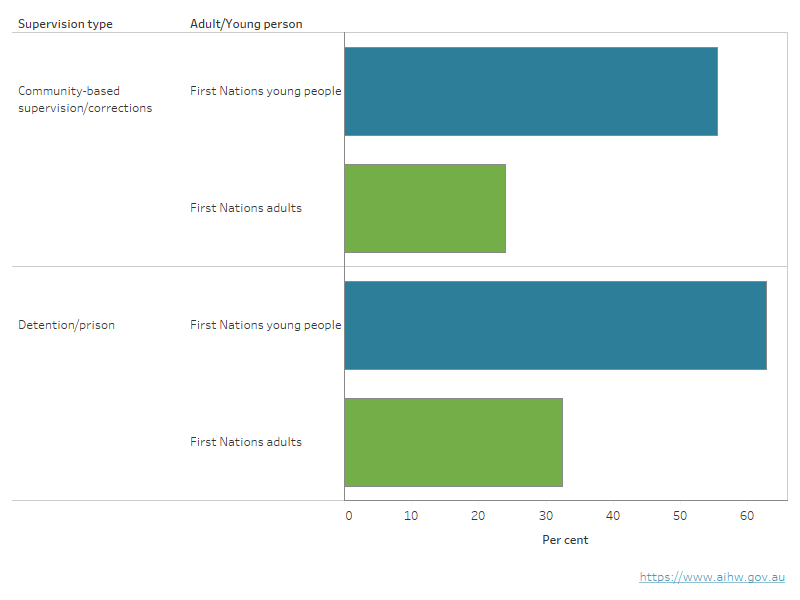

Young people aged 10–17 under youth justice supervision were more likely to identify as First Nations people than adults under supervision. More than half (55%) of young people aged 10–17 supervised in the community and almost 1 in 4 (24%) adults in community corrections were First Nations people (Figure 9.3).

Similarly, on an average day in 2022–23, almost two-thirds (63%) of young people aged 10–17 in detention were First Nations people compared with one-third (33%) of adults in full‑time prison.

As a result, the level of First Nations over-representation was higher among the youth detention population on an average day in 2022–23 than among adults in full-time prison on an average day in the 2023 calendar year (Figure 9.3). Available ABS data for First Nations and non-Indigenous adults are crude rates, by calendar year.

First nations young people aged 10–17 (30 per 10,000) were about 27 times as likely as non‑Indigenous young people to be in detention (1.1 per 10,000). First nations adults (244 per 10,000) were about 18 times as likely as non-Indigenous adults to be in full-time prison (14 per 10,000) (ABS 2024b; Table S75a).

On an average day, among those under justice supervision, the proportion of young people aged 10–17 who were male was similar to the proportion of adults who were male:

- About 89% of young people in detention and 93% of adults in prison were male

- 77% of young people and 81% of adults supervised in the community were male (ABS 2023; tables S36a and S74a).

Figure 9.3: First nations young people under youth justice supervision and adults under adult criminal justice supervision on an average day, by type of supervision, 2022–23

This horizontal bar chart compares the proportion of young people and the proportion of adults, in community-based supervision/corrections and detention/prison who were First Nations. The figure shows that a higher proportion of young people under both types of supervision were First Nations, compared to adults.

Note: Data on young people under supervision are for 2022–23; available ABS data on adults under supervision are the average of monthly snapshots taken on the first day of the month from July 2022 to June 2023.

Sources: ABS 2023; tables S36 and S74.

Young people in detention were more than twice as likely as adults in prison to be unsentenced (that is, to be awaiting the outcome of their court matter or sentencing).

On an average day in 2022–23, 85% of young people aged 10–17 in detention were unsentenced compared with 38% of adults in prison (ABS 2023; Table S109a).

Australian and international approaches to youth justice

International agreements, standards and guidelines

Many countries have developed or revised their youth justice policies and practices over the last 30 years.

A major influencing factor has been the introduction of international agreements and guidelines by the United Nations. For example, under the United Nations’ 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, member states regularly report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. This convention has influenced youth justice systems in many countries, including the principles underpinning each system, and the decision-making processes. Australia has been a signatory to this convention since 1990.

Three additional influential United Nations agreements that relate specifically to youth justice are the:

- Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice 1985 (also known as the ‘Beijing Rules’)

- Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency 1990 (also known as the ‘Riyadh Guidelines’)

- Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty 1990 (also known as the ‘Havana Rules’).

Within the broad framework of these international agreements, the philosophies, systems and processes for dealing with young people involved in criminal behaviour vary substantially among countries. For instance, the United States of America has not ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, so its youth justice policies and practices are not bound by the Convention’s principles.

Age for treatment as a young person

Article 40 (3) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN 1989) encourages member states to establish a minimum age of criminal responsibility, but previously did not specify a particular age.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2019) recently issued an update to the International Standards for the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility. In paragraph 22 of its ‘General comment no. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in juvenile justice’, the Committee deemed the previously recommended age of criminal responsibility of 12 years to be too low.

The Committee now encourages state parties to ‘take note of recent scientific findings, and to increase their minimum age to at least 14 years’. It commends those that have set higher minimum ages at 15 and 16.

The recommendation to increase the minimum age of criminal responsibility reflects current research in child development and neuroscience which provides evidence that the capacity for abstract reasoning is not fully developed in children aged 12 and 13 (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child 2019).

In Australia, the Meeting of Attorneys-General (MAG) reviewed Australia’s age of criminal responsibility. The MAG noted that the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and the Northern Territory have committed to raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility, and states have supported the development of proposals to raise the age, having regard to any carve outs, timing and discussion of implementation requirements (MAG 2023). This followed on from the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory (Royal Commission and Board of Inquiry 2017) which recommended that Australia:

- raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 12

- keep young people aged 14 and under out of detention unless they have committed a serious crime or pose a serious risk to the community.

Since then, the Northern Territory became the first Australian jurisdiction to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility, in November 2022, from 10 to 12 years. The change was implemented in August 2023 (which is after the reporting period of this report).

The age of criminal responsibility varies considerably across countries. An investigation of 90 countries found that the minimum age of criminal responsibility ranged from 6 to 18; the median age was 13.5 (Hazel 2008).

In Australia, along with New Zealand, England and Wales, young people are deemed to have criminal responsibility if they are aged 10 or over (Table 9.1).

But there are some allowances for children in younger age brackets. For example, young people in New Zealand aged 10 or 11 can only be prosecuted for murder and manslaughter (Child Rights International Network 2024).

In Australia, young people aged between 10 and 14 are given the presumption of doli incapax, meaning that they cannot be held criminally responsible unless it can be proved beyond reasonable doubt that the young person knew that their conduct was wrong. In England and Wales, young people aged under 12 cannot be prosecuted for an offence, though the offence may be included on a child’s criminal record (Child Rights International Network 2024).

In other countries, minimum ages of criminal responsibility include 11 in Japan; 12 in Canada; 13 in Greece; 14 in Germany, Italy and Spain; and 15 in Scandinavian countries (Table 9.1).

Some countries have alternative programs to avoid sentencing young people of a certain age to penalties such as deprivation of liberty. For example, in Greece, where the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 13, young people aged 13–15 may be required only to undertake reformatory or therapeutic measures, rather than receive a penalty of detainment.

Similarly, in Japan, where the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 11, young people aged 11–14 may be required to attend Juvenile Training Schools administered by the Ministry of Justice Correction Bureau rather than receive detention.

Table 9.1: Minimum age of criminal responsibility, by selected countries

Age (years) | Country |

|---|---|

10 | Australia(a), England, New Zealand, Wales |

11 | Japan |

12 | Belgium, Canada, Israel, Netherlands |

13 | Greece |

14 | Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain |

15 | Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden |

16 | Portugal |

(a) In Australia, 2 territories have raised the age of criminal responsibility: the Northern Territory raised it to 12 in August 2023; the Australian Capital Territory raised it to 12 in November 2023 and will raise it to 14 in mid-2025. Neither of these changes affect the 2022–23 reporting year.

Source: Child Rights International Network 2024.

Almost all countries have separate criminal justice systems for young people and adults, each with their own legislation.

The age at which individuals are processed as adults in the justice system is referred to as ‘criminal majority’. In Australia, the age of criminal majority is 18 in all jurisdictions. In Queensland, legislation to increase the age of criminal majority to 18 was enacted on 12 February 2018; before then, it was 17.

This is consistent with the typical age of criminal majority internationally (18), though it does vary between countries. Countries with a higher minimum age of criminal responsibility tend to have a higher age of criminal majority (Hazel 2008).

Principles, services and outcomes

Key principles established in the United Nations’ agreements and guidelines include:

- the ability to divert young people away from further involvement with the youth justice system, where appropriate

- the notion that young people should be detained only as a last resort, and for the shortest appropriate time (UN 1985, 1989).

The principle of detention as a last resort can be found in youth justice legislation in each state and territory in Australia.

Diversion is also a key principle of youth justice systems in all jurisdictions in Australia. This takes various forms, including:

- complete diversion from the system (such as an informal warning by police)

- referral to services outside the system (such as drug and alcohol treatment programs)

- diversion from continued contact with the system by the police or courts (through mechanisms such as conferencing – a facilitated meeting to discuss the offence and its impact, and to make a plan for action).

Again, there are wide variations between countries, and various diversionary approaches have emerged since the 1960s (Hazel 2008).

The police often play a key role in diversionary action, as they are generally the first point of contact a young person has with the justice system. In a 1998 United Nations survey, 19 of 51 countries surveyed allowed diversion to be instituted by the police (Hazel 2008).

The types of outcomes and sentences available for young offenders vary among countries. For example, young people in custody in the Netherlands can be released to take part in training courses or treatment during their sentences. Other outcomes include intermittent custody (such as night or weekend detention) and training in various forms, such as in Austria where trainees receive a wage throughout their vocational training (Hazel 2008).

Rates of young people in detention in various countries generally reflect the principles and operation of their respective youth justice systems. High rates are commonly seen in countries that operate under what is often termed a ‘justice model’, which emphasises accountability and punishment. Lower rates are seen in countries that operate under a ‘welfare model’, which focuses on rehabilitation and meeting the needs of the young person (Noetic Solutions 2010).

Countries with lower rates of young people in detention tend to adopt the principle of custody as a last resort (Hazel 2008).

Some countries have alternated between the justice and welfare models, and aspects of both approaches are increasingly used in many countries. The Australian youth justice system has typically used elements of both the welfare and justice models (Richards 2011).

International information on numbers of young people involved in youth justice systems as a whole is limited, but some data are available on numbers and rates of young people in detention in selected countries.

On an average day in 2022–23, the rate of young people in youth detention in Australia (2.7 per 10,000 young people) was higher than in England and Wales (0.9 per 10,000) and Canada (2.4 per 10,000), but lower than in the United States of America (6.3 per 10,000) (Table 9.2, see footnotes for the differences in measurement).

Rates of young people in detention are similar to or lower than those for the previous reporting periods for Australia (2.7 per 10,000), England and Wales (0.8), the United States (9.4) and Canada (2.5).

Table 9.2: Young people aged 10–17 in detention on an average day, by selected countries, 2022–23

Number/rate | Australia(a) | England and Wales | Canada(b) | United States of America |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Number | 707 | 441(c) | 459 | 20,955(d) |

Number per 10,000 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 6.3 |

(a) Data for 2022–23.

(b) Data for young people aged 12–17 in detention on an average day during 2021–22.

(c) Average monthly population of young people in custody April 2022 and March 2023 (remand and sentenced).

(d) Number in youth detention in 2021.

Sources: Office for National Statistics 2022; Puzzanchera et al. 2023; Sickmund et al. 2022; Statistics Canada 2024; Youth Custody Service 2024; YJ NMDS: tables S74a and S75a.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023) Corrective services, Australia, June quarter 2023, ABS, Australian Government.

ABS (2024a) Recorded crime – offenders, 2022–23, ABS, Australian Government.

ABS (2024b) Prisoners in Australia, 2023, ABS, Australian Government.

Child Rights International Network (2024) Minimum ages of criminal responsibility around the world, CRIN.

Farrington D (1986), ‘Age and crime’, In: Tonry M and Morris N (eds), Crime and justice: an annual review of research, Volume 7, The University of Chicago Press.

Hazel N (2008) Cross-national comparison of youth justice, Youth Justice Board for England and Wales.

MAG (Meeting of Attorneys-General) (2023) Council of Attorneys-General communique. Canberra: Age of Criminal Responsibility Working Group Report 2023.

Noetic Solutions (2010) Review of effective practice in juvenile justice: report for the Minister for Juvenile Justice, New South Wales Department of Human Services.

Office for National Statistics (2022) Population estimates for England and Wales, mid-2021, [data set], Office for National Statistics.

Puzzanchera C, Sladky A and Kang W (2022) Easy access to juvenile populations: 1990–2020, National Centre for Juvenile Justice.

Richards K (2011) Technical and background paper: measuring juvenile recidivism in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology.

Rocque M, Posick C and Hoyle J (2015), ‘Age and crime’, In: The Encyclopedia of Crime and Punishment, Jennings WG (ed.), doi.org/10.1002/9781118519639.wbecpx275.

Royal Commission and Board of Inquiry (2017) Final report - Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, report to the Northern Territory Government and the Australian Government, Royal Commission and Board of Inquiry, Darwin.

Sickmund M, Sladky TJ, Puzzanchera C and Kang W (2022) Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement, (EZACJRP).

Statistics Canada (2023) Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2021–2022, Statistics Canada, accessed 22 February 2024.

Ulmer J and Steffensmeier D (2014) ‘The age and crime relationship: social variation, social explanations’, In: Beaver KM, Barnes J and Boutwell BB (eds), The nurture versus biosocial debate in criminology: on the origins of criminal behavior and criminality, doi.org/10.4135

/9781483349114.n24.

United Nations (1985) United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (‘Beijing Rules’), adopted by General Assembly resolution 40/33 on 29 November 1985, United Nations General Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland

United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by General Assembly resolution 44/25 on 20 November 1989, United Nations General Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland.

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2019) General comment No. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in the child justice system, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Youth Custody Service (2024) Youth Justice Statistic 2022/23, UK Ministry of Justice.