Changing patterns of work

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Changing patterns of work, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Changing patterns of work. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/changing-patterns-of-work

MLA

Changing patterns of work. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/changing-patterns-of-work

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Changing patterns of work [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/changing-patterns-of-work

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Changing patterns of work, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/changing-patterns-of-work

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

The public health measures implemented to contain the spread of COVID-19 (such as widespread social distancing, national lockdowns, and activity/business-related restrictions) had a considerable impact on the working arrangements of many Australians. Many of these changes to working arrangements that were accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic show no signs of reverting to pre-pandemic levels. This page examines changes in working patterns in Australia, including working from home, internal migration, and job mobility.

Data are drawn from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) as well as other sources as described in the Data sources used on this page box below.

The Household, Income, and Labour Market Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey

The HILDA Survey commenced in 2001 and is managed by The Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (University of Melbourne) and funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). HILDA is Australia’s first nationally representative longitudinal household-based panel study following more than 17,000 working age members (over 15 years) of randomly selected Australian households over the course of their lifetime.

HILDA collects information on household and family relationships, family dynamics, economic and subjective wellbeing, labour market measures, income, employment, health, and education. Australian households are interviewed annually, providing a picture of longer-term trends and the recurrence of specific life circumstances, for example, poverty, unemployment, or welfare reliance (DSS 2022). This page uses data covering the period 2019–2021.

ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey

The ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey commenced in April 2020, with surveys covering differing topics related to the impacts of COVID, including questions on working from home arrangements. The survey was initially administered on a weekly basis and became less frequent from August 2020, with the latest available data from April 2022 (ABS 2022b).

Taking the Pulse of the Nation Survey

The Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey (TTPN), which began in April 2020, is administered by the Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research and, since 2022, in partnership with Roy Morgan. The survey was conducted bi-weekly until 2022, at which point it became monthly. It asks questions concerning current and emerging issues facing Australians. It is a representative sample of Australia, stratified to reflect the Australian adult population in terms of age, gender, and location (Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research 2022a).

The data presented on this page is based on survey responses across a number of waves from April 2021 to May 2022, on around 2,900 respondents who were working and had tasks they could perform at home.

Recruitment Experiences and Outlook survey

The National Skills Commission conducts the Recruitment Experiences and Outlook survey to monitor recruitment activity and conditions. Up to 14,000 businesses around Australia are invited to respond to the survey each year (Jobs and Skills Australia 2023).

Additional questions were added to the survey to better understand the impact of COVID-19 on businesses. Between 16 November 2020 and 5 February 2021, around 2,000 employers from 19 industries responded to these additional questions; it is these data that are reported on this page (National Skills Commission 2021).

Working from home

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced several changes to working arrangements, many of which are still in place and will likely remain into the future in some capacity; working from home is one example.

Prior to the pandemic (before 1 March 2020), 13% of people aged 18 and over with a job reported working from home all or most days according to the ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey. Following the lockdowns and restrictions in the early months of the pandemic to contain the spread of COVID-19, the proportion working from home all or most days more than doubled to around 26–31% between September 2020 and February 2021. It then declined to around 22–23% in April–May 2021, presumably reflecting fewer lockdowns in place around the country at this time, before increasing again to 30% by April 2022 – over twice as high as prior to the pandemic.

Results from this survey also highlighted that the proportion of people working from home at least one day per week also increased in the 2 years to April 2022, from 24% before 1 March 2020, increasing to 39–41% from September 2020 to February 2021, and dropping slightly to 36% in April and May 2021. By April 2022, 46% of people had worked from home at least once per week (in the last 4 weeks), the highest level recorded since the pandemic began in March 2020 (ABS 2021a; ABS 2022a).

The sustained increase in working from home suggests there may not be a return to pre-pandemic levels. Indeed, the results from the TTPN survey from July 2022 suggest that 88% of Australian workers would like to work from home at least partially, and 60% would prefer a hybrid work arrangement with days in both the office and at home (Melbourne Institute Applied Economic and Social Research 2022a). Many workers under the age of 54 have reported that they would leave their job or seek alternative employment if they were not able to access flexible work options (Ruppanner et al. 2023).

It is worth noting that some population groups in particular, such as caregivers or people living with chronic illnesses, may stand to benefit from more flexible work arrangements (Ruppanner et al. 2023).

Labour productivity

Working from home may affect productivity (that is, the measure of output per unit of labour) of employees in different ways. For example, it may have hindered productivity due to the physical distance between colleagues and challenges in collaborating and exchanging information. On the other hand, many employees have an improved work-life balance due to the elimination of their daily commute and being better rested for work as a result (Productivity Commission 2021).

Most people in paid employment who had increased the amount of time they spent working from home at the start of the pandemic reported little change in productivity. According to self-reported data from HILDA, almost 3 in 5 (58%) respondents indicated that productivity was the same or better following an increase in hours worked from home – 24% reported positive impacts, 33% no change in productivity, and 42% reported negative impacts. It is worth noting that this reporting is from the earlier months of the pandemic (in 2020), when many employees were forced to work from home at short notice, potentially with inadequate workstations, and with many families required to supervise children undertaking remote learning (Melbourne Institute Applied Economic and Social Research 2022b). It is also important to note that productivity as it is reported in HILDA is self-reported, and not an objective or economy-wide measure; employers may have a different view than those reported by individual employees in the survey.

This finding that working from home has a minimal impact on productivity is consistent with other studies. One such study conducted a randomised control trial to investigate the effects of hybrid work arrangements on the attrition, job satisfaction and productivity of both managerial and non-managerial knowledge workers. This study found that – despite a drop in productivity being one of the more commonly touted criticisms of working from home – there was no evidence to suggest a substantial positive or negative impact of hybrid working on productivity (Bloom et al. 2023).

Job satisfaction

In terms of job satisfaction, there are advantages and disadvantages in working from home. It may provide employees with a greater sense of autonomy and control. On the other hand, if employees are excessively monitored it may decrease organisational attachment (Productivity Commission 2021). This relationship may depend to some extent on the amount of time spent working from home (or away from the office) (Allen et al. 2015).

Research from the Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research found a positive association between working from home and job satisfaction for women, but not for men (Laß et al. 2023). This analysis used a linear fixed effects model to examine job satisfaction of people employed in both 2019 and 2021 (but who only worked from home in 2021) and controls for the characteristics of workers – including, for example, age, partnership status, employment type, supervisory responsibilities, employer size and industry. Mothers who worked at home for 3 days per week and in the workplace for 2 days had a 12% increase in average job satisfaction. This may be related to increased opportunities to undertake both work and family responsibilities (Laß et al. 2023).

Technology enabling working from home

The increase in regularly working from home in a job or business relied on employers making the most out of available technologies, such as digital collaboration tools and cloud-based project planning tools (National Skills Commission 2021).

The National Skills Commission’s Recruitment Experiences and Outlook survey of around 2,000 employers between 16 November 2020 and 5 February 2021 collected information on the impact of COVID-19 on businesses, including the implementation of automation and new technologies. This survey found that 33% of employers had implemented automation or new technology during the pandemic, which was a major factor enabling remote work (National Skills Commission 2021).

Internal migration

The option to work from home can shift how people make decisions about the physical location of their home and workplace. For example, with employees working from home, the distance, time, and cost of a commute may no longer feature so heavily when deciding where to work or live (Doling and Arundel 2020). This may create opportunities for people to move further away from central business districts.

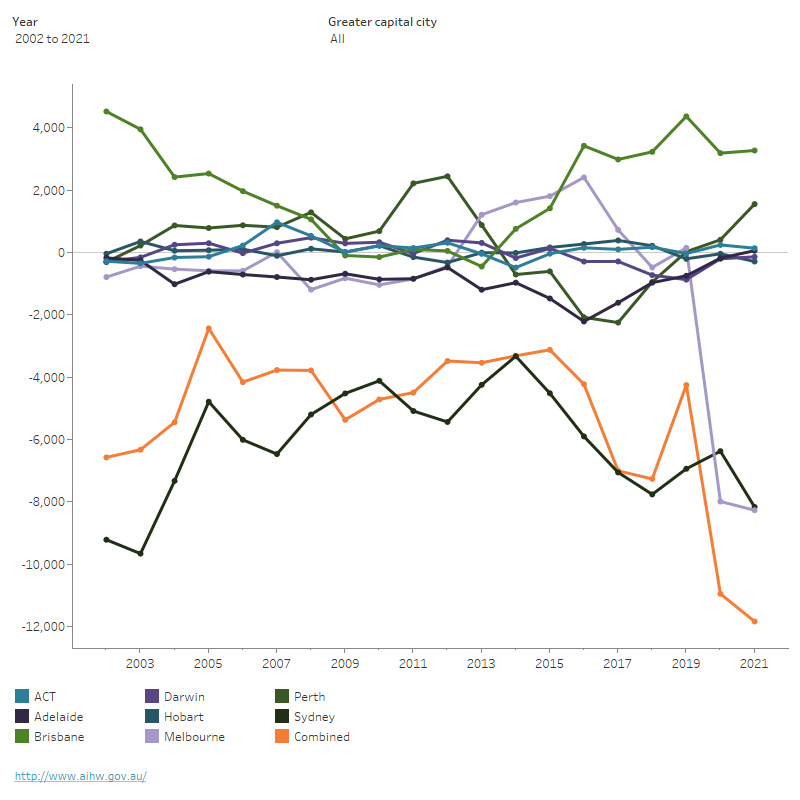

While Australian capital cities have had net losses from internal migration since 2001, this was accelerated at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. From June 2002 to June 2019, the net loss in the population of all Australian capital cities ranged from 2,400 to 8,600 people each quarter. In March 2020, this rose to a net loss of 10,100.

By March 2021 (the latest available data), the net loss for capital cities from internal migration had increased slightly again to 11,800 (Figure 1). Over this quarter, Brisbane gained the most people (3,300), while Melbourne and Sydney lost the most people (8,300 and 8,200, respectively) (ABS 2021b). This steep decline was the result of both fewer arrivals in capital cities from, and an increased number of departures to, non-capital city areas.

Figure 1: Net internal migration in Australian capital cities, 2002–2021

The line chart shows the number of net internal migration across all Australian capital cities between June 2002 and March 2021. All Australian capital cities have had net losses from internal migration since 2002. Net loss from internal migration ranged from 2,400 to 7,300 in all Australian capital cities from June 2002 to June 2019 (before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic), but increased steeply at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. As at March 2021, Brisbane showed the largest number of net internal migrants, whereas Melbourne showed a steep decline in the number of net internal migrants between 2020 and 2021.

Notes

- ‘Combined’ is the net internal migration across all Greater capital cities.

- Net internal migration is the number of arrivals minus the number of departures and can be either positive or negative.

- The figure presents data from the June quarter in each corresponding year.

Source: ABS 2021b Table 1.

Job mobility

The pandemic has had a large impact on the job mobility of many Australians. Job mobility on this page refers to employed people who have changed jobs, left jobs or lost their jobs in the 12 previous months.

Changing jobs

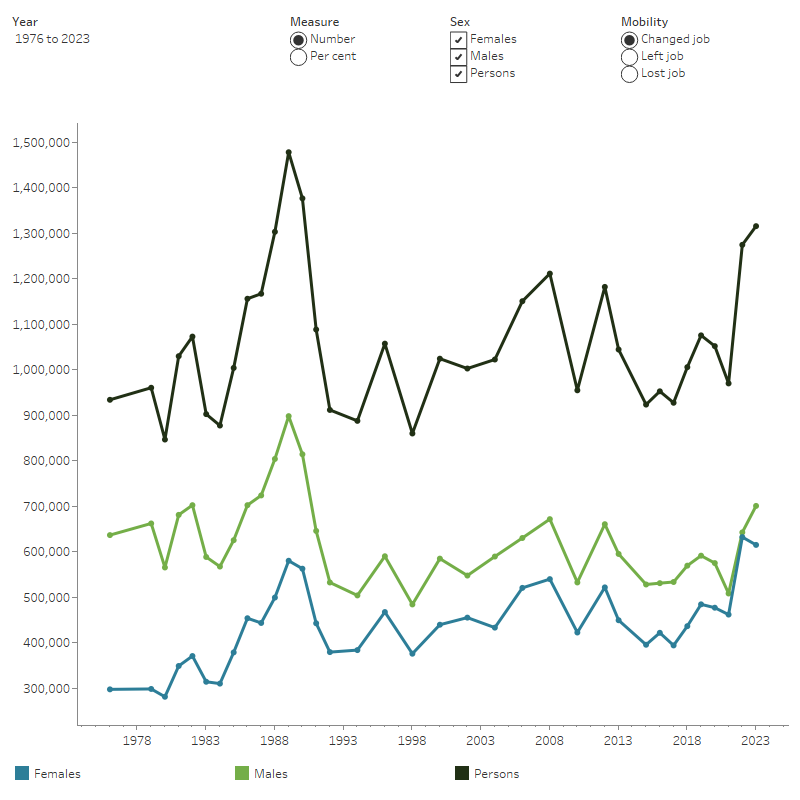

The proportion of employed people who change employer or business in the previous 12 months has been gradually declining since the 1990’s – from 20% of employed people in the 12 months to February 1989, to 8.5% by February 2019, declining further to 7.5% by February 2021. By February 2022 this had increased to the highest level in a decade (9.5%; Figure 2), which equates to 1.3 million people changing jobs in the 12 months to February 2022. This was around 215,600 more people than in the 12 months to February 2020. Between February 2022 and February 2023 the proportion of employed people who changed jobs remained steady at 9.5%.

This increase in job mobility since February 2021 may be due to workers following up on plans to change jobs following a pause during the pandemic, or taking advantage of the strong labour market (Black and Chow 2022).

Figure 2: Persons who changed jobs or left or lost a job in the 12 months to February of each year 1976–2023

The line chart shows the number and proportion of employed people who changed jobs or left or lost a job in the 12 months to February of each year from 1976 to 2023. In the 12 months to February 2021, there was a decline in the number of employees leaving their jobs (from 1.3 million in 2019–20 to 1.1 million in 2020–21). Over the same period, there was a slight increase in the number of people who lost their jobs, from 670,500 in 2019–20 to 718,300 in the 12 months to 2020–21. In the 12 months to February 2022, however, these patterns had reversed with an increasing number of people leaving jobs (up to 1.6 million people) and a decreasing number of people losing their jobs (down to 522,500 people), as compared with the previous year.

Note: The figure presents the number of people who changed jobs in the 12 months to February of each year as a proportion of all employed people, and the number of people who left or lost jobs in the 12 months to February each year as a proportion of the population aged 15 and over.

Sources: ABS 2018: Table 17, 2023: Table 1.

Leaving or losing jobs

In the early months of the pandemic (the 12 months to February 2021), employees were less likely to leave their jobs, and slightly more likely to lose their jobs, as compared with the previous year.

In the 12 months to February 2021, there was a decline in the number of employees leaving their jobs (from 1.3 million in 2019–20 to 1.1 million in 2020–21; Figure 2). This period covers the early months of the pandemic, during which time many employees were reluctant to change jobs due to economic uncertainty, fewer advertised roles, and the JobKeeper program introduced in March 2020 which assisted people in maintaining employment with their current employer (Black and Chow 2022).

Over the same period, there was a slight increase in the number of people who lost their jobs, from 667,600 in 2019–20 to 715,700 in 2020–21 (or from 3.3% to 3.5% of the population aged 15 and over; Figure 2). Over half (55%) of these job losses were due to people being retrenched (the termination of an employee when their position is no longer required). It is likely that the number of people recorded as losing their jobs would have been substantially higher without the introduction of the JobKeeper payment (see ‘Chapter 4 The impacts of COVID-19 on employment and income support in Australia’ in Australia’s welfare 2021: data insights for further details).

In the 12 months to February 2022, however, these patterns had reversed with an increasing number of people leaving jobs and a decreasing number of people losing their jobs, as compared with the previous year – 7.7% of the population aged 15 and over left their jobs in 2021–22, which is the highest since 2011–12 (7.5%), and 2.4 percentage points higher than the previous year (5.3%). The most common reason for people leaving their jobs was to get a better job or just wanting a change – 53% of all people who left their jobs, compared with 39–47% each year since 2015.

In the 12 months to February 2022, 2.5% of the population aged 15 and over lost their jobs, compared with 3.5% in 2020–21. Of all the job losses, 38% were due to people being retrenched. While retrenchment rates increased at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (from 1.1% to 4.4% between February and May 2020 quarters), retrenchment rates remained lower than previous recessions (AIHW 2021). For example, during the recessions of the early 1990s, the annual retrenchment rate reached 7.2% in 1991.

In the year to February 2023, the proportion of the population aged 15 and over who left their jobs continued to grow to 8.4%, while the proportion who lost their jobs remained steady at 2.5%.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on changing patterns of work, see:

- University of Melbourne HILDA Survey publications

- Jobs and Skills Australia Recruitment Experiences and Outlook Survey.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) Participation, Job Search and Mobility, Australia, February 2018, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

ABS (2021a) Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey May 2021, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

ABS (2021b) Regional internal migration estimates, provisional, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

ABS (2022a) Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey April 2022, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

ABS (2022b) Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey methodology, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

ABS (2023) Job mobility, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 30 January 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Chapter 4: The impacts of COVID-19 on employment and income support in Australia in Australia’s Welfare 2021: data insights, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

Allen TD, Golden TD and Shockley KM (2015) ‘How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings’, Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 16(2):40–68.

Black S and Chow E (2022) Job Mobility in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Reserve Bank of Australia, accessed 31 May 2023.

Bloom N, Han R and Liang J (2023) How hybrid working from home works out, National Bureau of Economic Research working paper series, National Bureau of Economic Research, accessed 31 May 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) Longitudinal Studies, Living in Australia: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey fact sheet, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

Doling J and Arundel R (2020) The Home as Workplace, Centre for Urban Studies, Working Paper Series No. 43. May 2020, accessed 5 July 2023.

Laß I, Vera-Toscano E and Wooden M (2023) Working from home, COVID-19 and job satisfaction, Working Paper No. 04/23 March 2023, Melbourne Institute, accessed 29 March 2023.

Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research (2022a) Taking the Pulse of the Nation, 11 July 2022, Melbourne Institute, accessed 20 February 2023.

Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research (2022b) The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey: Selected findings from Waves 1 to 20, Melbourne Institute, accessed 20 February 2023.

National Skills Commission (2021) State of Australia’s Skills 2021: now and into the future, National Skills Commission, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

Productivity Commission (2021) Working from home: research paper, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

Ruppanner L, Churchill B, Bissell D, Ghin P, Hydelund C, Ainsworth S, Blackhman A, Borland J, Cheong M, Evans M, Frermann L, King T and Vetere F (2023) 2023 State of the Future of Work, The University of Melbourne, accessed 28 April 2023.