Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care

The ATSICPP states the decision to place a child in out-of-home care can only be made after all active efforts to keep a child safely at home have been exhausted.

The nationally consistent definition of out-of-home care includes overnight care for children aged under 18 who are unable to live with their families due to child safety concerns, and where the carer receives a financial payment. It generally excludes children on third-party responsibility orders as the minister or executive no longer has guardianship of children on these orders.

Refer to the Out-of-home care section of CPA 2021–22: Insights for more information on out-of-home care and third-party parental responsibility orders.

How many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were in out-of-home care?

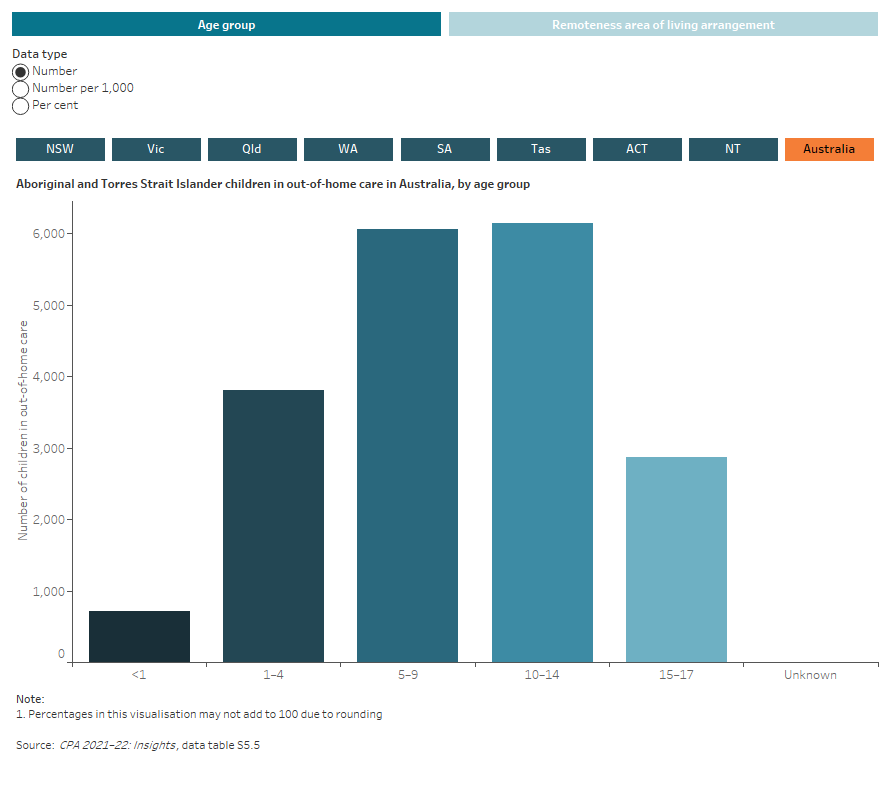

At 30 June 2022, around 19,400 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were in out-of-home care. Of these:

- children aged 10–14 years made up around a third (6,100 children) of the children in out-of-home care

- 44% (8,500) were living in major cities (Figure 5).

Sources: CPA 2021–22: Insights, data tables S5.5 and S5.9.

Figure 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care, by age group and remoteness area

This interactive data visualisation shows the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were in out-of-home care at 30 June 2022, by age group and remoteness area. Data are displayed for each state and territory and Australia.

In 2021–22, 71% (13,900) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care had been continuously in care for 2 years or more, known as long-term care. Of these children:

- 71% (9,800) were aged 5–14 years

- 41% (5,700) were on a long-term guardianship order in a relative/kinship care arrangement, followed by 34% (4,700) who were on a long-term guardianship order in a foster care arrangement.

Sources: CPA 2021–22: Insights, data tables S5.15 and S5.16.

In 2021–22, around 4,100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were admitted to out-of-home care. The admission rate was highest for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under one at 41 per 1,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, compared with 12 per 1,000 or less for other age groups.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Insights, data table S5.1.

Children in care can experience further abuse or neglect, for example, by their carer or another person in the household or care facility. In 2021–22, around 570 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were the subject of a substantiation assessment of abuse in care.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Safety of children in care, data table S9.2.

Refer to the CPA 2021–22: Safety of children in care section for more information.

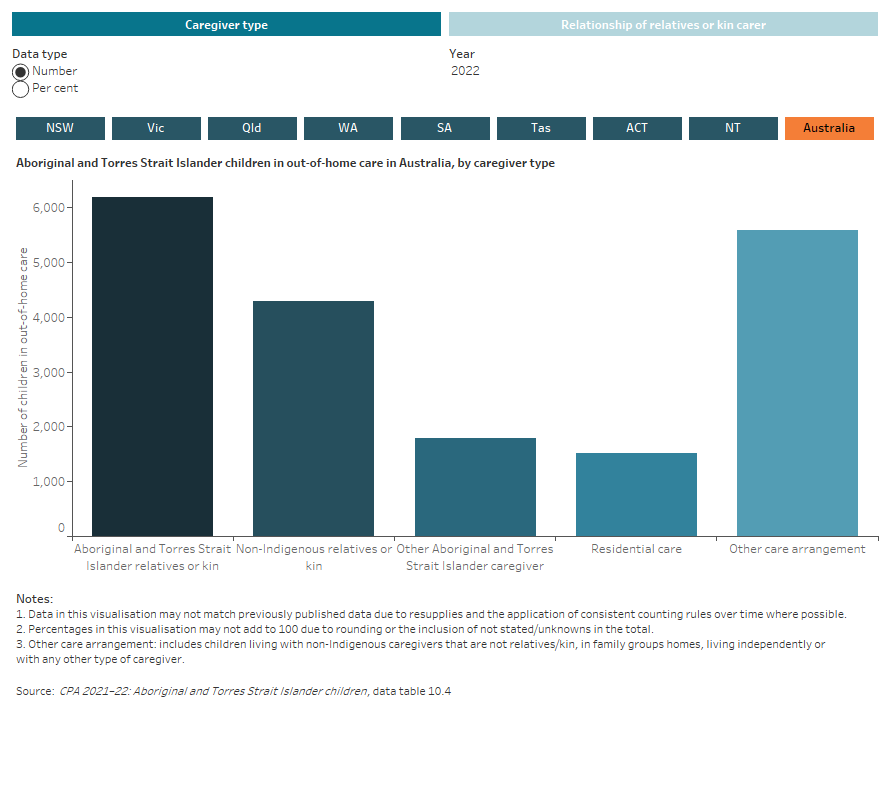

Placement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care

Where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are placed in out-of-home care, the ATSICPP identifies a placement hierarchy that seeks to maintain as high a level of connection as possible to family and culture (SNAICC 2017). Children should be placed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or extended family members, or other relatives and family members.

- Of the 19,400 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care, around 10,500 (54%) were placed with their relatives or kin. Of these, children were most frequently placed with a grandparent, aunt, uncle or sibling as their carer (53% or 5,600).

- Around 1,800 (9.2%) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were placed with a non-relative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander caregiver.

- Around 7,200 (37%) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were not placed with either relative or kin, or non-relative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander caregivers (Figure 6).

More information on the specific placement hierarchy can be found in Understanding and applying the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle.

Sources: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data tables 10.4 and 10.7.

Figure 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care, by caregiver type

This interactive data visualisation shows the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were in out-of-home care at 30 June 2017 to 2022, by caregiver type, and where children are placed with relatives/kin, relationship of relative or kin carer. Data are displayed for each state and territory and Australia.

According to the ATSICPP, it is important that children be placed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives as soon as possible when placed in out-of-home care (SNAICC 2017). In 2021–22, 1,100 (26% of 4,100 children) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were placed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin in their first out-of-home care placement.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data table 10.6.

Reconnection to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives and kin through placement change

Where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were unable to initially be placed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin, the Placement Principle states that efforts should be made to reconnect the children with their family, community, culture and country through a placement change. In 2021–22, around 5,100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children had more than one placement in an out-of-home care episode. Of these:

- around 730 (16%) children were reconnected with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin through their last placement change in 2021–22 (for example, a child is placed with a non-Indigenous carer and has a placement change to reside with their Aboriginal grandmother)

- 1,300 (26%) children were reconnected or stay connected to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin through their last placement change in 2021–22 (for example, a child is placed with their Torres Strait Islander aunt and has a placement change to reside with their Torres Strait Islander grandfather).

Source: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data table 10.9.

Around 540 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 0–16 years were reconnected to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin through a placement change in 2020–21 and remained in out-of-home care for at least 12 months. Of these:

- 450 (83%) remained with the same Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin for at least 12 months

- 470 (87%) remained with any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin for at least 12 months.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data table 10.10.

Of the 2,100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 0–16 years whose first placement was not with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin and who remained in out-of-home care for at least 12 months, 315 (15%) were reconnected with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or kin within 12 months.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data table 10.11.

Placement with siblings in out-of-home care

As well as having carers who are relatives or kin, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children should be placed with their siblings where possible to keep strong relationships and support connection to family (SNAICC, 2019). Factors such as safety and carer availability may impact the ability for child protection agencies to place children with their siblings. In 2021–22, of the 12,700 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who have at least one known sibling in out-of-home care, 8,900 (70%) were placed with at least one of their siblings.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data table 10.8.

Maintaining and supporting connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care

The connection element of the ATSICPP relates to support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care to maintain or re-establish connections to their family, community, culture and country (SNAICC 2017). Cultural plans include details such as a child’s cultural background and actions taken to maintain their connection to culture. It should be noted that the data do not provide information on the quality of the plan, or whether it was implemented.

At 30 June 2022, of the 17,700 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care who were required to have a cultural support plan, 78% (13,800) had a current cultural support plan. Since 2017 there has been an increase of around 5,300 children with a current cultural support plan.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, data table 10.5.

Has the number of children in out-of-home care changed over time?

Between 30 June 2018 and 30 June 2022, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care increased from around 17,200 to around 19,400 children.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Insights, data table T2.

From 2017–18 to 2021–22, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children admitted to out-of-home care each year fluctuated from around 3,800 to around 4,000 children.

Source: CPA 2021–22: Insights, data table S5.17.