Asthma

Page highlights

- Asthma is a long-term lung condition caused by narrowing of the airways when they become inflamed.

- Health risk factors for asthma include smoking, being obese or insufficiently active.

- An estimated 2.7 million (11%) people in Australia reported having asthma in 2017–18.

- In 2020–21, people with asthma had higher rates of ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health (23%) and ‘high’ to ‘very high’ psychological distress (30%) compared with those without the condition.

- Asthma accounted for 2.5% of total disease burden and 35% of the total burden of disease for all respiratory conditions in 2023.

- Asthma was the leading cause of total burden in children aged 1–9 years.

- In 2020–21, an estimated $851.7 million was spent on the treatment and management of asthma, representing 0.6% of total health system expenditure and 19% of expenditure for all respiratory conditions.

- Asthma was the underlying cause of death for 351 deaths or 1.4 deaths per 100,000 population in 2021, representing 0.2% of all deaths.

Treatment and management of asthma

- 18% of people aged 40 and under met the definition for poorly controlled asthma (dispensed 3 or more reliever prescriptions per year).

- 33% of people aged 50 and under met the threshold for better management of moderate to severe asthma (dispensed 3 or more preventer medicines per year).

- There were 25,500 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of asthma in 2021–22 (99 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).

- The hospitalisation rate among children aged 0–14 was markedly higher compared with people aged over 15 (225 and 70 per 100,000 population, respectively).

- In 2020–21, there were 56,600 emergency department (ED) presentations for asthma, about 230 presentations per 100,000 population.

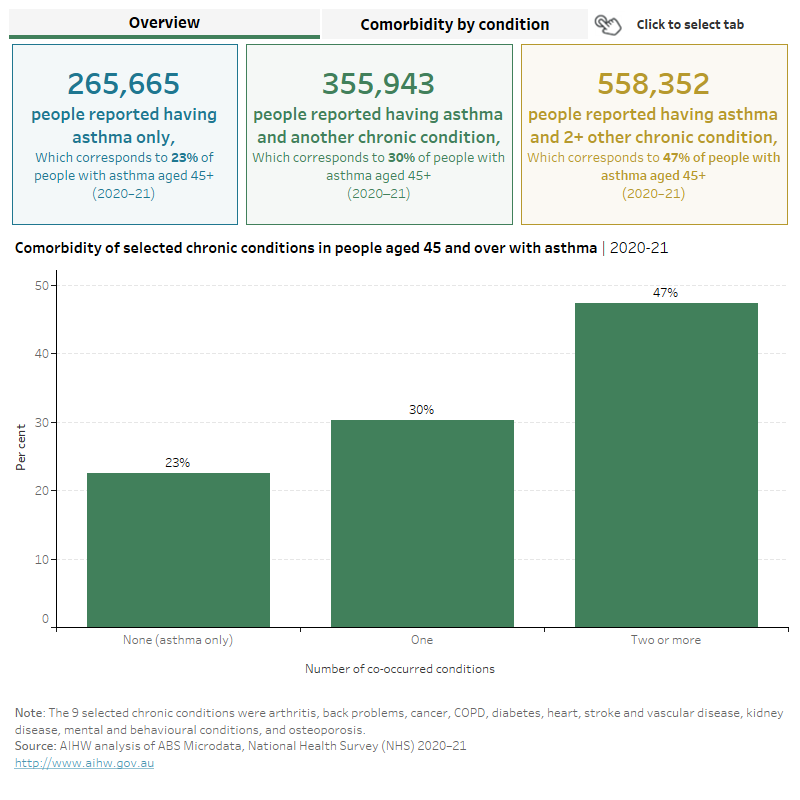

In 2020–21, 78% of people with asthma aged 45 and over, had at least one other chronic condition – of the 9 conditions analysed, the top 3 comorbidities for asthma were arthritis (42%), back problems (33%) and heart, stroke and vascular disease (31%).

What is asthma?

Asthma is a common chronic condition that affects the airways (the breathing passage that carries air into our lungs). People with asthma experience episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing, chest tightness and fatigue due to widespread narrowing of the airways (NACA 2022).

It is worth noting that while asthma shares similar symptoms and can co-occur or overlap with other respiratory conditions such as Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchiectasis, it remains a distinct condition for diagnosis and treatment.

The National Asthma Indicators

In 2018, the National Asthma Strategy (the Strategy) was released. It outlines Australia’s national response to asthma and informs how existing limited health care resources can be better coordinated and targeted across all levels of government (NACA 2018).

The Strategy includes 10 national asthma indicators designed to provide valuable information for policymakers about the status of asthma in Australia.

The National Asthma Indicators – an interactive overview (PDF 2.9MB) was published in 2019. These indicators have been updated and are included throughout this report where relevant and a summary is also published, see Chronic respiratory conditions: National asthma indicators.

What causes asthma?

The fundamental causes of asthma are not completely understood. The strongest risk factors for developing asthma are a combination of genetic predisposition with environmental exposure to inhaled substances and particles that may provoke allergic reactions or irritate the airways. Asthma triggers can include:

- viral respiratory infections

- allergens (indoor or outdoor)

- tobacco smoke and air pollution

- chemical irritants, including in the workplace

- strong odours, such as perfume.

Other triggers can include cold air, change in temperature, thunderstorms, extreme emotional arousal such as anger or fear, hormonal changes, pregnancy, and physical exercise. Certain medications can also trigger asthma: aspirin and other non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, and beta-blockers (used to treat high blood pressure, heart conditions and migraine) (WHO 2017).

Impact of natural events on asthma

Natural disasters or extreme weather changes can affect human health drastically, and events that affect air quality can have a direct impact on asthma. Two natural events that have affected asthma in recent times are thunderstorm asthma and the bushfires of 2019–20.

Thunderstorm asthma

Thunderstorm asthma can occur suddenly in spring or summer when there is a lot of pollen in the air and the weather is hot, dry, windy and stormy. People with asthma and/or hay fever need to be extra cautious to avoid flare-ups induced by thunderstorm asthma between September and January in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland because it can be very serious (NACA 2019).

In 2016, a serious thunderstorm asthma epidemic was triggered in Melbourne when very high pollen counts coincided with adverse meteorological conditions, resulting in 3,365 people presenting at hospital emergency departments over 30 hours, and 10 deaths (Thien et al. 2018). Following this event, a thunderstorm asthma forecasting system has been developed to give Victorians early warning of possible epidemic thunderstorm asthma events in pollen season (Victoria State Government 2022). See Natural environment and health.

Australian bushfires of 2019–20

The bushfires that swept across Australia in 2019–20 resulted in 33 deaths, destruction of over 3,000 houses and millions of hectares of land (Parliament of Australia 2020). Bushfire smoke exposure was significantly associated with an increased risk of respiratory morbidity (Liu et al. 2015).

Nationally, hospitalisation rates increased for asthma and COPD coinciding with increased bushfire activity during the 2019–20 bushfire season (AIHW 2021a). For asthma, the highest increase of 36% was observed in the week beginning 12 January 2020, compared with the previous 5-year average (2.4 and 1.7 per 100,000 population).

For emergency department presentations for asthma, the highest increase of 44% was observed in the week beginning 12 January 2020 compared with the previous bushfire season (4.7 and 3.3 per 100,000 population). See Natural environment and health.

Heath risk factors associated with asthma

Asthma shares several modifiable risk factors with other chronic conditions, such as:

- tobacco use (smoking or exposure to cigarette smoke)

- exposure to environmental hazards (for example, exposure to air pollutants)

- overweight/obesity

- sedentary lifestyle.

These risk factors may increase the chance of developing asthma in the first place (either in childhood or as an adult) or may increase the chance that a person with asthma will develop additional health problems. Risk factors vary according to the person's age, and according to the type of asthma that they have. In people with asthma, risk factors associated with an increased risk of flare-ups include:

- having frequent episodes of coughing, shortness of breath, and wheezing (for example, more than 2 days/week)

- not taking preventer treatment regularly

- frequent reliever inhaler use

- comorbidities (for example, mental illness, obesity, chronic rhino sinusitis)

- exposure to smoking, allergens or air pollution (GINA 2019).

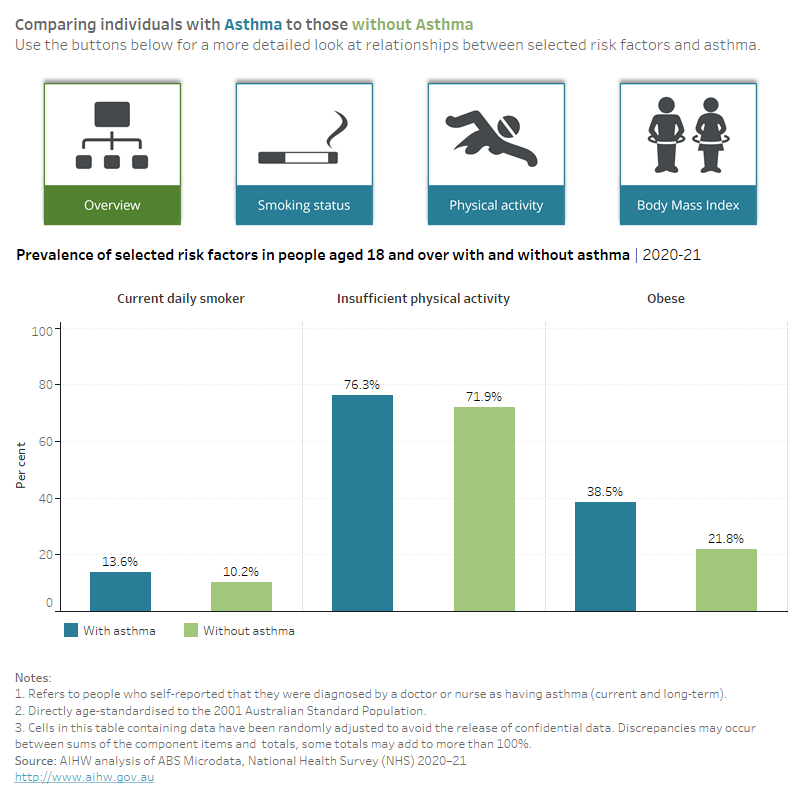

Based on the 2020–21 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS), people with asthma were:

- more likely to be current daily smokers compared with people without asthma (14% and 10%, respectively)

- less likely to have never smoked compared with people without asthma (58% and 63%, respectively).

- less likely to meet the 2014 physical activity guidelines compared with people without asthma (24% and 28%, respectively)

- 1.8 times as likely to live with obesity compared with people without asthma (39% and 22%, respectively), using self-reported body mass index (BMI). Note that self-reported data is likely to underestimate the true prevalence (Figure 1).

For support to quit smoking, speak to your GP or call the Quitline (13 7848).

Figure 1: Prevalence of selected risk factors in people aged 18 and over with and without asthma, 2020–21

This figure shows that people with asthma were more likely to be ex-smokers than those without asthma.

Age differences in risk factors in people with asthma

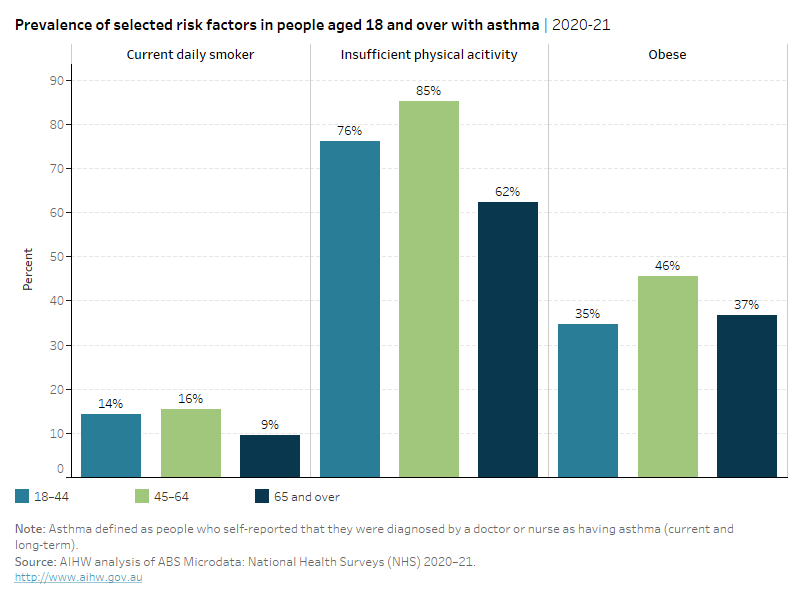

For people with asthma, the prevalence of risk factors varies by age. In 2020–21, people with asthma:

- aged 45–64 had the highest prevalence of each of the selected risk factors (16% were current daily smokers, 85% did not meet the 2014 physical activity guidelines and 46% were living with obesity)

- aged 18–44 had the next highest prevalence of each of the selected risk factors (14% were current daily smokers, 76% did not meet the 2014 physical activity guidelines and 35% were living with obesity)

- aged 65 and over had the lowest prevalence of smoking and physical activity (9% were current daily smokers and 62% did not meet the 2014 physical activity guidelines) but had a slightly higher prevalence for obesity than those aged 18–44 (37% were living with obesity) (Figure 2).

Smoke free laws, tobacco price increases, plain cigarette packaging and greater exposure to mass media campaigns may contribute to lower smoking rates among older Australians (Wakefield et al. 2014).

Figure 2: Prevalence of selected risk factors in people aged 18 and over with asthma, by age group, 2020–21

This figure shows that of the selected risk factors, the prevalence of insufficient physical activity was highest across all age groups.

How common is asthma?

National asthma indicator 1: The proportion of the Australian population who report having current and long-term asthma

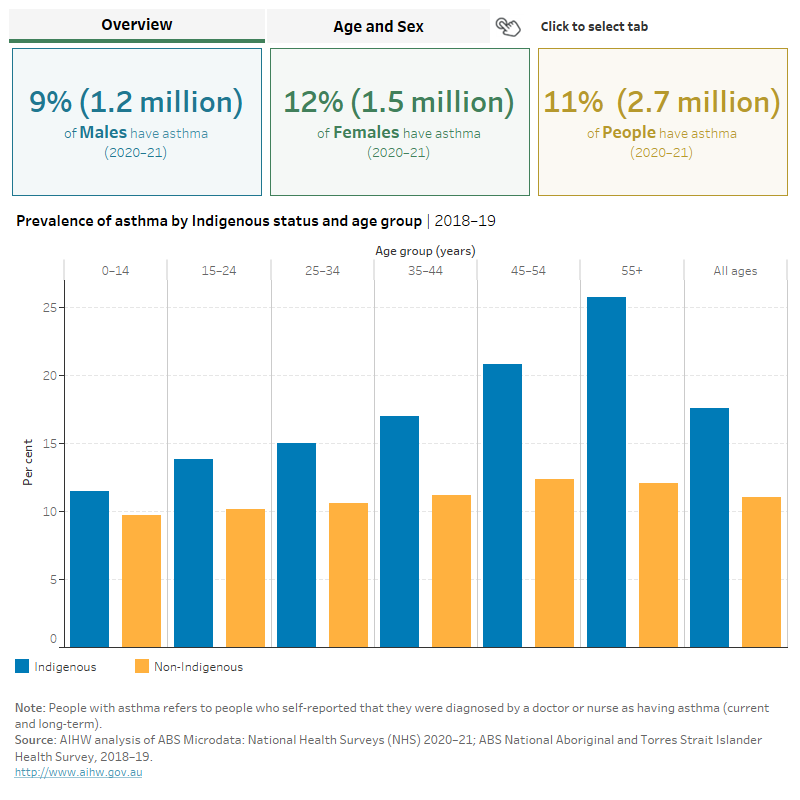

An estimated 2.7 million (11%) people in Australia reported having asthma, according to the 2020–21 NHS (ABS 2022a).

Box 1: Comparability of the ABS National Health Survey 2020–21

The ABS National Health Survey (NHS) 2020–21 was collected online during the COVID-19 pandemic and is a break in time series. Data should be used for point-in-time analysis only and cannot be compared with previous years. Thus, only 2020–21 is reported here.

For more information, see National Health Survey: First Results methodology 2020–21.

Prevalence by age and sex

According to the 2020–21 NHS, the prevalence of asthma was:

- similar for boys and girls aged 0–14 (9.3% and 7.7%, respectively)

- higher for females than males over the age of 15 for all age groups except for those aged 25–34 (Figure 3).

This change in prevalence for males and females in adulthood is likely due to a complex interaction between changing airway size and hormonal changes that occur during adolescent development, as well as differences in environmental exposures (Dharmage et al. 2019).

Prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) uses ‘First Nations people’ to refer to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people in this report.

According to self-reported data from the ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), in 2018–19:

- around 128,000 (16%) First Nations people reported having asthma, down from 18% in 2012–13 (ABS 2019)

- the prevalence of asthma for First Nations people increased with age, from 12% in children aged 0–14 to 26% in those aged 55 and over

- the prevalence of asthma was higher among First Nations females compared with First Nations males (18% and 13%, respectively).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 population groups, First Nations people were 1.6 times as likely to report having asthma as non‑Indigenous Australians (18% and 11%, respectively) (Figure 3).

For more information, see First Nations people with asthma.

For more information on respiratory conditions in First Nations people, see the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Measure 1.04 (AIHW 2023a).

Figure 3: Prevalence of asthma, by Indigenous status, sex and age

This figure shows that the prevalence of asthma is higher in First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians.

Variation between population groups

Based on the 2020–21 NHS, people:

- born in Australia were more than twice as likely as those born overseas to have asthma (13% compared with 6%, respectively)

- living in Inner regional areas were more likely to have asthma compared with those living in Outer Regional and Remote areas (13% and 9%, respectively)

- with a profound or severe core activity limitation were almost 3 times as likely to have asthma as those with no disability (23% and 8%, respectively) (ABS 2022a).

Additional data on asthma prevalence by country of birth and other culturally and linguistically diverse measures are also reported using the ABS 2021 Census in Chronic health conditions among culturally and linguistically diverse Australians, 2021 (AIHW 2021b).

Impact of asthma

Asthma has varying degrees of impact on the physical, psychological, and social wellbeing of people living with the condition, depending on disease severity and the level of control. People with asthma are more likely to report poor quality of life, especially those with severe or poorly controlled asthma (ACAM 2011).

How does asthma affect quality of life?

National asthma indicator 2: Impact of asthma on quality of life

2a: The proportion of people aged 18 and over with and without asthma who rated their health status as excellent or very good.

2b: The proportion of people aged 18 and over with and without asthma who experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress.

2c: The proportion of people aged 18 and over who reported that asthma interfered with daily activities 2 or more times in the last 4 weeks.

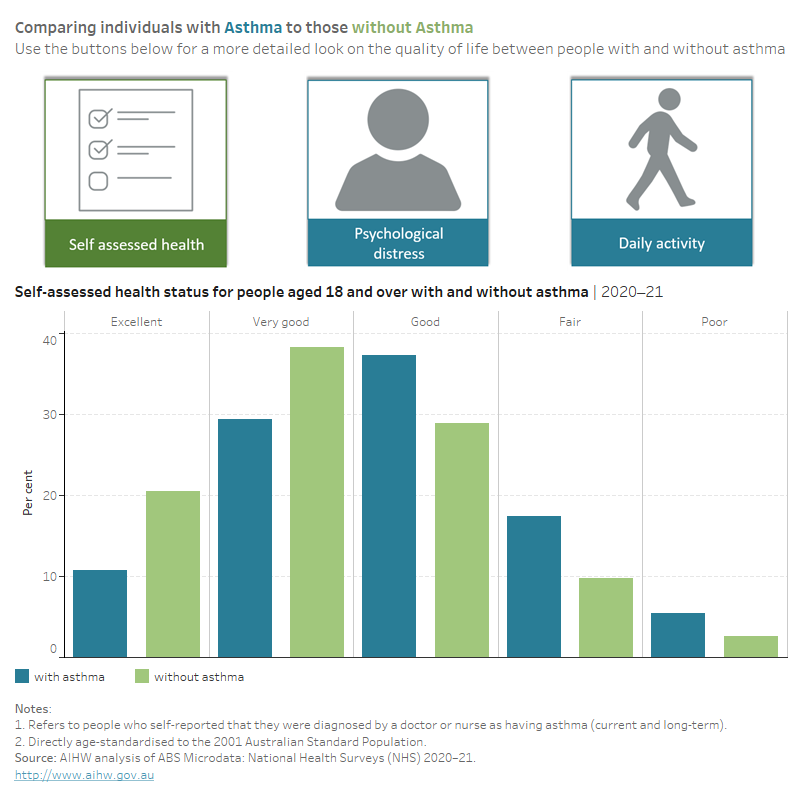

In 2020–21, people with asthma aged 18 and over were:

- 1.9 times as likely to report having ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health compared with people without asthma (23% and 12%, respectively)

- 1.6 times as likely to experience ‘high’ to ‘very high’ levels of psychological distress compared with those without asthma (30% and 19%, respectively) (Figure 4).

Twenty-one per cent of people with asthma reported that asthma interfered with their daily activities 2 or more times in the past 4 weeks. Eight per cent of people reported interference once in the past 4 weeks (daily activities included going to school, playing with friends, going to work, exercising, and getting around places) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Quality of life measures (age standardised) for people aged 18 and over with and without asthma, 2020–21

This figure shows that 11% of those with asthma, compared with 22% of those without, reported having excellent health.

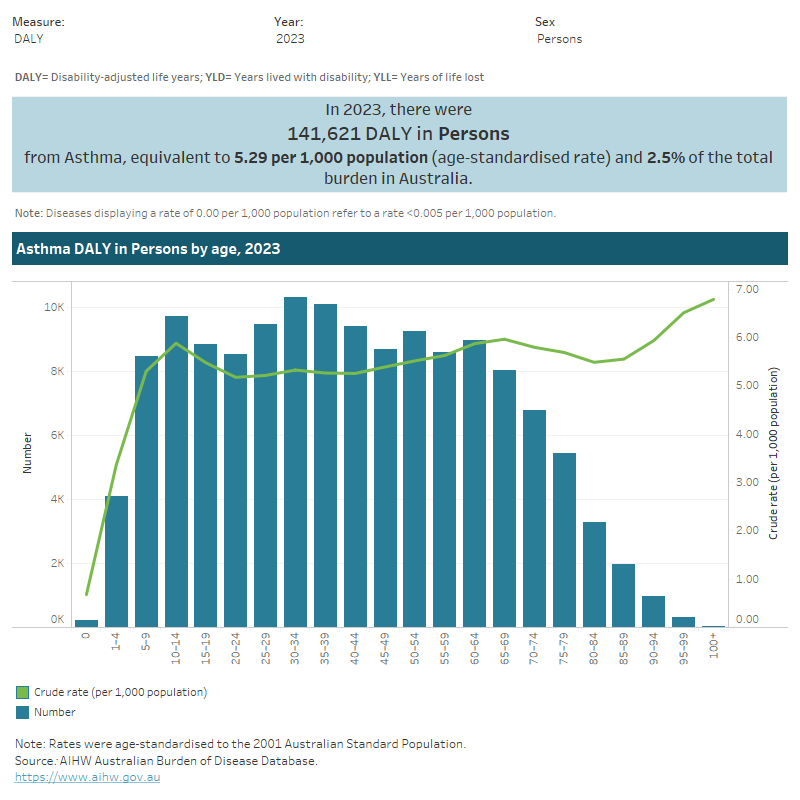

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

In 2023, asthma accounted for 2.5% of total disease burden (DALY); 4.4% of non-fatal burden (YLD), and 0.3% of fatal burden (YLL). Within the respiratory disease group, asthma accounted for 35% of total burden (DALY); 52% of non-fatal burden (YLD); and 5.4% of fatal burden (YLL) (AIHW 2023b).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023:

- the overall rate of burden from asthma was 1.2 times as high for females compared with males (5.8 and 4.9 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- asthma was the leading cause of burden for children aged 1–4 and 5–9 years (11%, and 13% of total burden (DALY), respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Burden of disease due to asthma, by sex, age and year

This figure shows that the burden of disease due to asthma decreases for persons aged 60–64 and over.

Trends over time

Between 2003 and 2023, the age standardised rate of asthma burden increased by 8% (from 4.9 to 5.3 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) – or 0.4% per year on average. This increase was driven by non-fatal burden (YLD).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023.

Variation between population groups

In 2018, the age standardised rate of burden from asthma:

- was highest for people living in Remote and very remote areas and lowest for people living in Major cities (7.3 and 5.0 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- was highest for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) and lowest for people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (6.9 and 3.7 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 6) (AIHW 2021c).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden.

Figure 6: Burden of disease due to asthma for remoteness area and socioeconomic group, by sex and year

This figure shows that the prevalence of asthma was similar for those living in Inner and Outer regional areas in 2018.

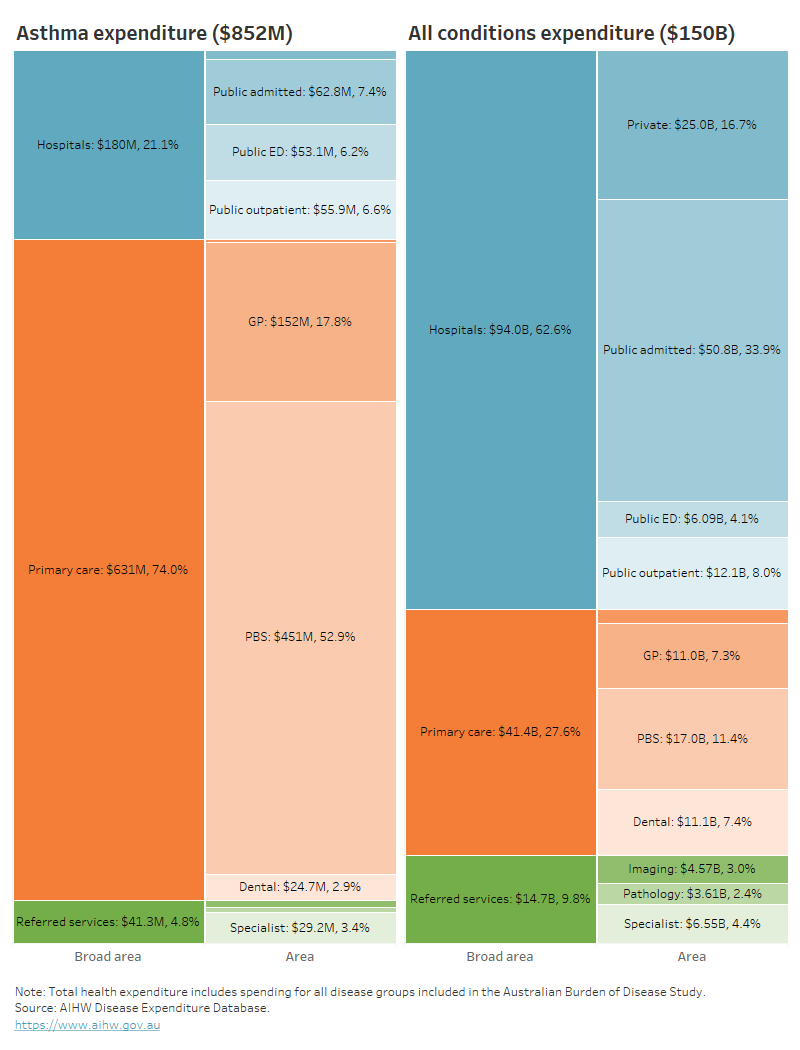

Health system expenditure

Understanding the contribution of asthma to direct health care expenditure helps to explain the economic impact of the disease. Furthermore, knowledge of the relative contribution of the various health care sectors (hospital, out-of-hospital medical care, and pharmaceutical) to overall asthma-related expenditure assists in planning interventions to optimise this expenditure.

It should also be acknowledged that financial costs represent a small part of the overall economic impact caused by asthma. A report on the estimated economic cost of asthma in Australia was published in 2015 and data included in the 2018 National Asthma Strategy (Deloitte Access Economics 2015; NACA 2018).

National asthma indicator 3: Health expenditure on asthma

In 2020–21, an estimated $851.7 million of expenditure in the Australian health system was for asthma, representing 0.6% of total health expenditure and 19% of expenditure of all respiratory conditions (AIHW 2023c).

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–21:

- primary care represented 74% ($630.5 million) of asthma expenditure, around 2.7 times the primary care portion for all disease groups (28%). The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) proportion of asthma expenditure was especially large in comparison to the average, 4.7 times the proportion for all disease groups (53% and 11%, respectively)

- hospital services accounted for 21% ($179.9 million) of asthma spending, which was 3.0 times lower than the hospital proportion for all disease groups (63%). The public hospital emergency department proportion of asthma expenditure was especially large in comparison to the average, 1.5 times the proportion for all disease groups (6.2% and 4.1%, respectively)

- referred medical services represented 4.8% ($41.3 million) of asthma expenditure, which was less than the proportion for all disease groups (9.8%) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Asthma expenditure attributed to each area of the health system, with comparison to all disease groups, 2020–21

This figure shows that 18% of asthma expenditure was attributed to the general practice services.

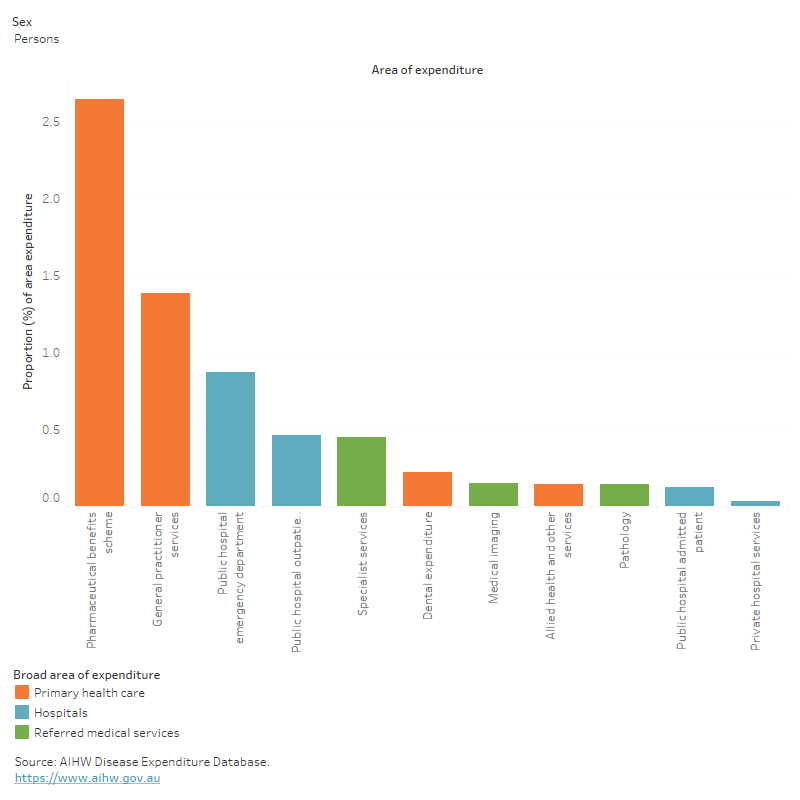

In 2020–21, asthma accounted for:

- 2.6% ($450.6 million) of all PBS expenditure – ranking 11th of all diseases/conditions

- 1.4 % ($152.0 million) of all GP expenditure (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Proportion of expenditure attributed to asthma, for each area of the health system, 2020–21

This figure shows that 0.9% of public hospital emergency department expenditure was attributed to asthma.

Who is the money spent on?

In 2020–21:

- the age distribution of spending on asthma reflects the prevalence distribution, with the majority being spent on older age groups (55% for people aged 45 and over)

- 1.4 times more asthma expenditure was attributed to females compared with males ($477.5 million and $346.7 million, respectively), with the remaining $27.5 million (3.2%) unattributed to any sex.

For more information, see Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21.

In 2018–19, it was estimated that asthma expenditure per case was:

- 1.1 times greater for females compared with males ($290 and $265 per case, respectively)

- 44% lower than respiratory conditions as a group ($285 and $515 per case, respectively) (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors.

Investment in asthma research

Between 2000 and 2022, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) has expended $348 million towards research relevant to asthma.

Between its inception in 2015 and 31 March 2023, the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) has invested $283.8 million in 151 grants with a focus on respiratory health research. Of these, 8 grants ($11.3 million) focus on asthma research. Examples include:

- $2.4 million to the University of Newcastle for the project titled, A comprehensive digital solution to empower asthma and comorbidity self-management

- $1.6 million to the Queensland University of Technology for the project titled, Oral bacterial lysate to prevent persistent wheeze in infants after severe bronchiolitis; a randomised placebo-controlled trial (BLIPA; Bacterial Lysate in Preventing Asthma).

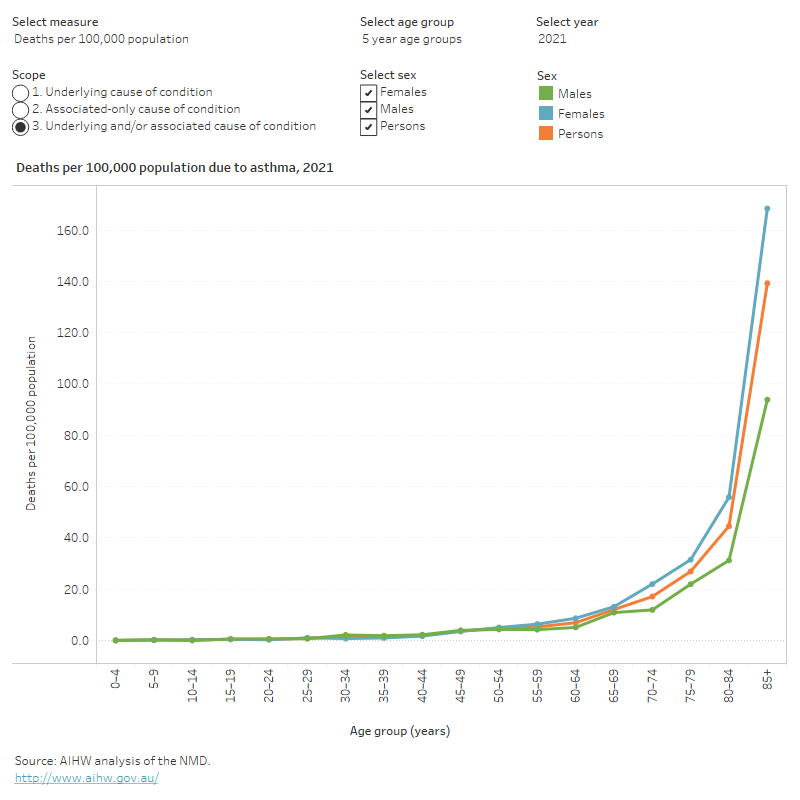

How many deaths were associated with asthma?

Asthma was recorded as an underlying cause of death for 351 deaths or 1.4 deaths per 100,000 population in Australia in 2021, representing 0.2% of all deaths and 2.6% of all respiratory deaths.

Asthma was more likely to be recorded as an associated cause of death. Asthma was recorded as an associated cause of death for an additional 1,641 deaths, resulting in a total of 1,992 deaths in Australian due to, or associated with, asthma. This represented 1.2% of all deaths and 4.3% of respiratory deaths.

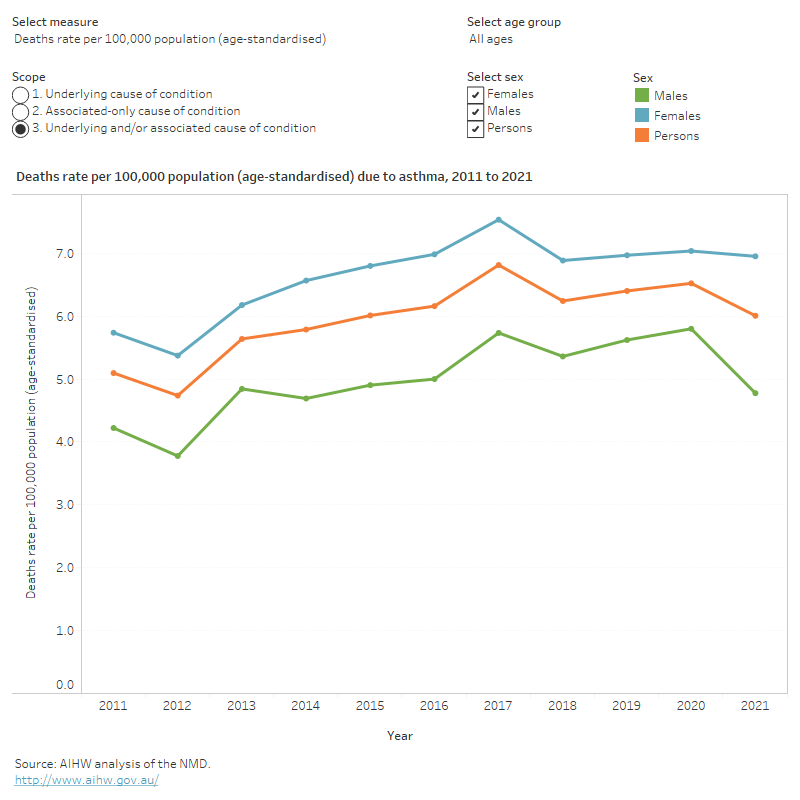

National asthma indicator 4: Deaths due to asthma

4a: The number of deaths (all ages) due to asthma per 100,000 population (age-standardised).

4b: The number of deaths (for those aged 5–34, 35–55 and 55 and over) due to asthma, per 100,000 population (age-standardised).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021, asthma mortality (as the underlying cause of death), in comparison to all deaths, was relatively concentrated amongst:

- older people (63% of asthma deaths were among people aged 75 and over, compared with 67% for total deaths)

- females (70% of asthma deaths were among females, compared with 48% of total deaths).

Asthma mortality rates by age and sex were similar as the underlying cause of death and any cause of death (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Age distribution for asthma mortality, by sex, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows the rate of asthma deaths (as underlying cause) in 2021 is highest for those aged 85 years and over (29 deaths per 100,000 population).

Trends over time

Age standardised mortality rates for asthma (as the underlying cause of death) between 2011 and 2021 were:

- relatively stable between 2011 and 2017, averaging 1.5 per 100,000 population, and then decreased to 1.1 per 100,000 population in 2021. The opposite trend is observed for asthma as any cause of death, which increased from 5.1 to 6.0 per 100,000 population

- consistently higher for females compared with males across all years. This pattern remains true for asthma as an underlying or associated cause of death (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Trends over time for asthma mortality, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows the rate of asthma deaths (as underlying cause) was lowest in 2021 with 1.1 deaths per 100,000 population.

Variation between population groups

In 2021, age standardised mortality rates for asthma (as the underlying cause of death) were:

- 1.6 times higher for people living in Outer regional areas, compared with people living in Major cities (1.4 and 0.9 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively)

- 2.3 times higher for people living in lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage), compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (1.4 and 0.6 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively).

First Nations people experience higher mortality from chronic lower respiratory diseases (such as asthma, bronchiectasis, emphysema, and other chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) than non-Indigenous people in Australia (AIHW 2023a; Australian Indigenous HealthinfoNet 2018).

In the 5-year period from 2017–2021, across Australia, there were 74 deaths of First Nations people due to asthma (AIHW 2023d).

Asthma mortality rates among First Nations people:

- increased with age, from 0.2 deaths per 100,000 population in children aged 0–14, to 6.6 deaths per 100,000 population in those aged 65 and over

- were 1.6 times as high for females compared with males (2.1 and 1.3 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 population groups, asthma mortality rates for First Nations people were 1.9 times as high as for non‑Indigenous Australians (2.5 and 1.3 per 100,000 population, respectively).

The asthma mortality rate differences between these population subgroups may be due to differences in smoking rates, access to health services, or other social and environmental factors. In Australia, smoking prevalence is higher among people living in more remote areas, among people living in areas of higher disadvantage, and among First Nations people (AIHW 2018).

For more information, see First Nations people with asthma.

For more information on mortality data, see Chronic respiratory condition mortality data tables 2023.

Treatment and management of asthma

In general, symptoms of asthma are easily controlled in most people by making lifestyle changes and using medications, so they can have normal lives. The main aims of asthma treatments are:

- to stop asthma from interfering with school, work, or play

- to prevent flare-ups or ‘attacks’

- to keep symptoms under control

- to keep lungs as healthy as possible (NACA 2022).

What medicines are used to treat asthma?

There are several medicines available to treat asthma. Different asthma medicines are used to achieve different goals, as follows:

- Relievers are used for the rapid relief of asthma symptoms. They can also be used before exercise to prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (constriction of the airways). Short-acting beta agonist medications (SABA) are the most used relievers (NACA 2022).

- Preventers are used every day in asthma control to minimise symptoms and reduce the likelihood of episodes or flare-ups. Inhaled corticosteroids are the most used preventers.

- Other medicines such as long-acting bronchodilators and biologics are used for management of difficult-to-treat asthma or as add-on options for management of severe asthma flare-ups.

Biologics are a relatively new class of medications which are increasingly being prescribed to those with severe asthma. They act like preventers but are not classified as such. They can only be prescribed by a respiratory specialist, and some are not yet covered by the PBS. Therefore, not all biologics are included in reporting on medications in this section.

A key focus of the National Asthma Strategy is to improve outcomes for those with severe or poorly controlled asthma (NACA 2018). Assessing the overall level of asthma control in the population can provide insight into the effectiveness of the management of asthma in the community and the need for further efforts in improving asthma management.

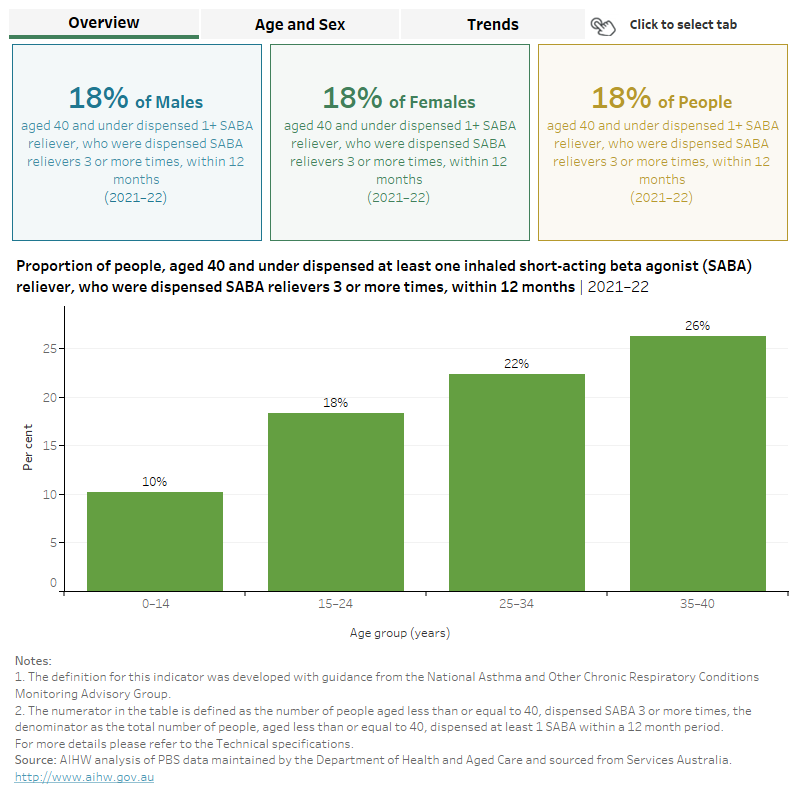

Reliever medication use for asthma control

Frequent use of relievers is an indicator of poor asthma control, with dispensing frequency used as a proxy for reliever use. In line with advice from the AIHW’s Chronic Respiratory Conditions Expert Advisory Group, the dispensing of reliever medicines 3 or more times in 12 months has been selected as the threshold for poor asthma control.

National asthma indicator 5: The proportion of people, aged 40 and under, dispensed at least one reliever, who were dispensed relievers 3 or more times, within 12 months

Analysis of 2021–22 PBS data shows that:

- of all people aged 40 and under who were dispensed at least one reliever, 18% were dispensed relievers 3 or more times within 12 months (Figure 11)

- the rate of dispensing relievers 3 or more times in 12 months was the same (18%) for males and females aged 0–40

- Twenty-six per cent of people aged 35–40 dispensed at least one reliever, were dispensed relievers 3 or more times in 12 months – higher than for all other age groups (Figure 11).

Rates have changed little since 2017–18 but for all age groups apart from 0–14, a spike can be seen in 2020–21 (Figure 8). The corresponding spike for those aged 0–14 is observed earlier, in 2019–20. This same trend is noted for preventer medications (Indicator 6) and may be related to anecdotal evidence that many people started to panic buy respiratory medication in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic where they had an existing condition. Bushfires in 2019–20 may also have contributed to this increase in dispensing of asthma medication.

From the end of March 2020 pharmacists were strongly encouraged to limit dispensing and sales of all therapeutic goods (especially salbutamol inhalers) generally to a one-month supply or one unit in response to the stockpiling occurring (DoHAC: TGA 2020). In October 2020, changes in legislation were enacted to limit dispensing of some asthma medication (mainly salbutamol) to a maximum of one pack per person (PSA 2022).

Figure 11: Proportion of people aged 40 and under dispensed at least one reliever, who were dispensed relievers 3 or more times within 12 months, by age and sex, 2017–18 to 2021–22

This figure shows that 22% of people aged 25–34 dispensed at least one reliever, were dispensed relievers 3 or more times within 12 months.

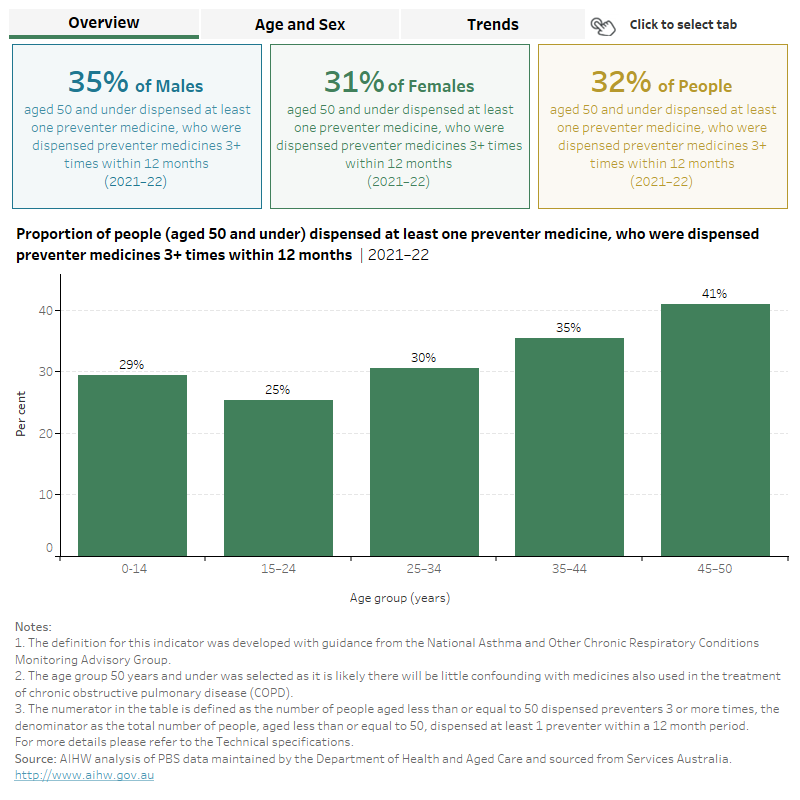

Preventer medication use for asthma control

Preventer medicine is the mainstay of asthma management, to minimise symptoms and exacerbations. National guidelines for the management of asthma recommend preventers to be taken regularly (either daily or twice daily) rather than intermittently (NACA 2022).

In line with advice from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's (AIHW) Chronic Respiratory Conditions Expert Advisory Group, the dispensing of these medicines 3 or more times in 12 months has been selected as the threshold for reflecting better management of moderate to severe asthma.

National asthma indicator 6: The proportion of people, aged 50 and under, dispensed at least one preventer medicine, who were dispensed preventer medicines 3 or more times, within 12 months

Analysis of 2021–22 PBS data shows that, of people aged 50 and under who were dispensed at least one preventer medicine, 33% were dispensed preventer medicines 3 or more times within 12 months. The rate of dispensing preventers 3 or more times in 12 months:

- increased with age from 25% for those aged 15–24, up to 41% for those aged 45–50

- was slightly higher for males compared with females (35% and 31%, respectively).

Males dispensed at least one preventer had higher rates of being dispensed preventers 3 or more times in 12 months compared with females irrespective of age (Figure 12).

Rates have changed little since 2017–18 but for all age groups apart from 0–14, a spike can be seen in 2020–21 (Figure 9). The corresponding spike for those aged 0–14 is observed earlier, in 2019–20. This same trend is noted for asthma control medications (Indicator 5), and as covered in detail in that section, may be due to stockpiling of medication during the COVID-19 pandemic and a subsequent restriction in dispensing of some medications to combat this. Bushfires in 2019–20 may also have contributed to this increase in dispensing of asthma medication.

For more information on medicines used to treat asthma and the national guidelines for asthma management, see the Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 2.2.

Figure 12: Proportion of people aged 50 and under dispensed at least one preventer medicine, who were dispensed preventer medicines 3 or more times within 12 months, by age and sex, 2017–18 to 2021–22

This figure shows that 29% of those aged 0–14 dispensed at least one preventer medicine, were dispensed preventer medicine 3 or more times within 12 months.

What role do GPs play in managing asthma?

General practitioners (GPs) play an important role in the management of asthma in the community. This role includes assessment, diagnosis, prescription of regular medications, education, provision of written action plans, and regular review as well as managing asthma flare-ups (Stanford Children’s Health 2020).

Until 2017, the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) survey was the most detailed source of data about general practice activity in Australia (Britt et al. 2016). In the decade up to 2015–16, according to this survey:

- asthma was one of the most frequently managed chronic problems

- the estimated rate of asthma management in general practice declined from 2.3 in 100 encounters to 2.0 in 100 encounters.

It is worth noting that there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection to monitor provision of care by GPs. See General practice, allied health and other primary care services.

For more information about management of asthma, see the Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 2.2: Management for children, adolescents, and adults.

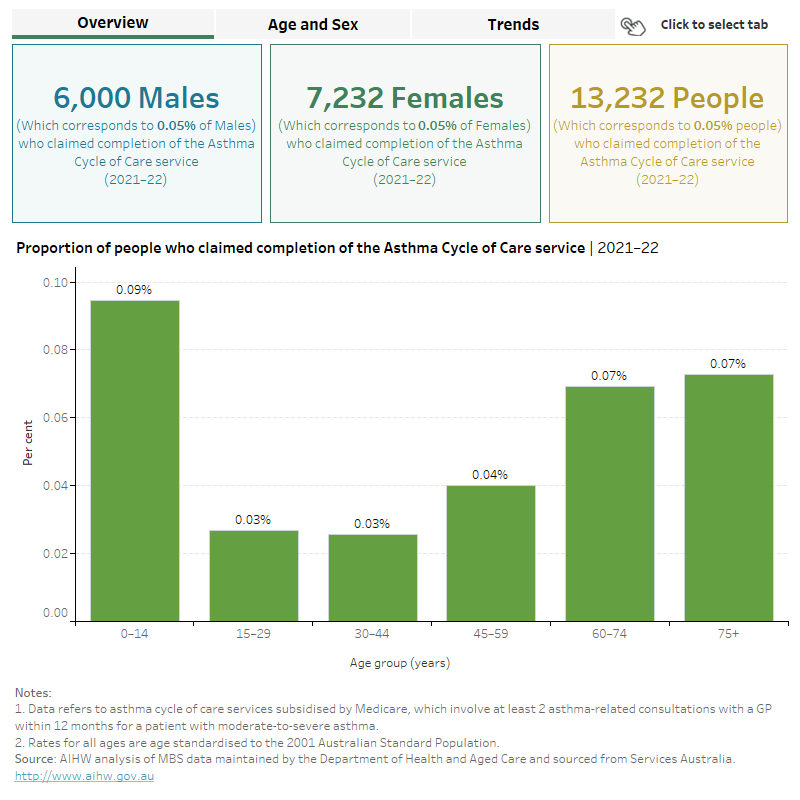

Asthma cycle of care

Asthma cycle of care claims are used as a proxy for GP care for asthma since no other data source is available. It involves at least 2 asthma-related consultations with a GP within 12 months for a patient with moderate-to-severe asthma. There are 12 MBS items for GP consultations that relate to the completion of an asthma cycle of care.

Asthma cycle of care data has been included for this update, but it should be noted that these items were removed from the Medicare Benefits Scheme as of 1 November 2022 and thus will not be used for reporting on GP encounters for asthma in future (RACGP 2022).

Data development work is being progressed to identify a suitable alternative to this data. Limitations of the asthma cycle of care data include that:

- patients may also use other forms of health care to manage their asthma, which are not covered by this cycle of care measure

- the denominator for this indicator includes all people in Australia not just those diagnosed with asthma.

National asthma indicator 7: The proportion of people who claimed the completion of the asthma cycle of care service

Analysis of Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) data shows that around 13,000 (0.1%) people claimed the completion of the asthma cycle of care in 2021–22, with little difference observed by sex after adjusting for age structure (Figure 13).

From 2017–18 to 2021–22, the proportion of people claiming the asthma cycle of care decreased from 0.3% to 0.1%. This decrease was noted for all age groups and was slightly greater for females compared with males (0.3% to 0.1% and 0.2% to 0.1%, respectively) (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Proportion of people who claimed the completion of the asthma cycle of care service, by age and sex, 2017–18 to 2021–22

This figure shows that around 4,500 children aged 0–14 claimed the completion of the asthma cycle of care service in 2021–22.

Asthma action plans

An asthma action plan is a written self-management plan which is prepared for patients with asthma by a health care professional to help them manage their condition and reduce the severity of acute asthma flare-ups. A patient’s individualised plan is developed to deal with their personal triggers, signs and symptoms, and medication (NACA 2022).

National asthma indicator 8: The proportion of people with asthma who have a written asthma action plan

According to the 2020–21 NHS:

- an estimated 34% of people with self-reported asthma across all ages had a written asthma action plan

- 69% of children aged under 14 had a written action plan compared with 23% of people aged 75 and over (ABS 2022a)

- across all ages, females were more likely than males to have a written asthma action plan (Figure 14).

It is likely that the age differences are due to schools and childcare facilities requiring that children with asthma have a health care provider issued asthma action plan (Asthma Australia 2022).

According to the 2018–19 NATSIHS, 32% of First Nations people had a written asthma action plan with those living in non-remote areas more likely to have a plan compared with those living in Remote areas (32% and 27%, respectively) (Figure 14).

For more information, see First Nations people with asthma.

Figure 14: Proportion of people with asthma who have a written asthma action plan, by age and sex, and for Indigenous Australians by remoteness area, 2020–21

This figure shows that 20% of people aged 25–34 with self-reported asthma had a written action plan.

What role do hospitals play in treating asthma?

People with asthma require admission to hospital when flare ups or ‘attacks’ are potentially life-threatening or when they cannot be managed at home or by a GP.

National asthma indicator 9: The number of hospital admissions where asthma was the principal diagnosis, per 100,000 population (age-standardised)

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that in 2020–21, there were 38,000 hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of asthma, representing 0.3% of all hospitalisations.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of asthma, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of asthma.

In 2020–21:

- there were 25,500 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of asthma, representing 0.2% of all hospitalisations in Australia, and 99 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- asthma accounted for 51,000 bed days, representing 0.2% of all bed days

- 63% of asthma hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 2.6 days.

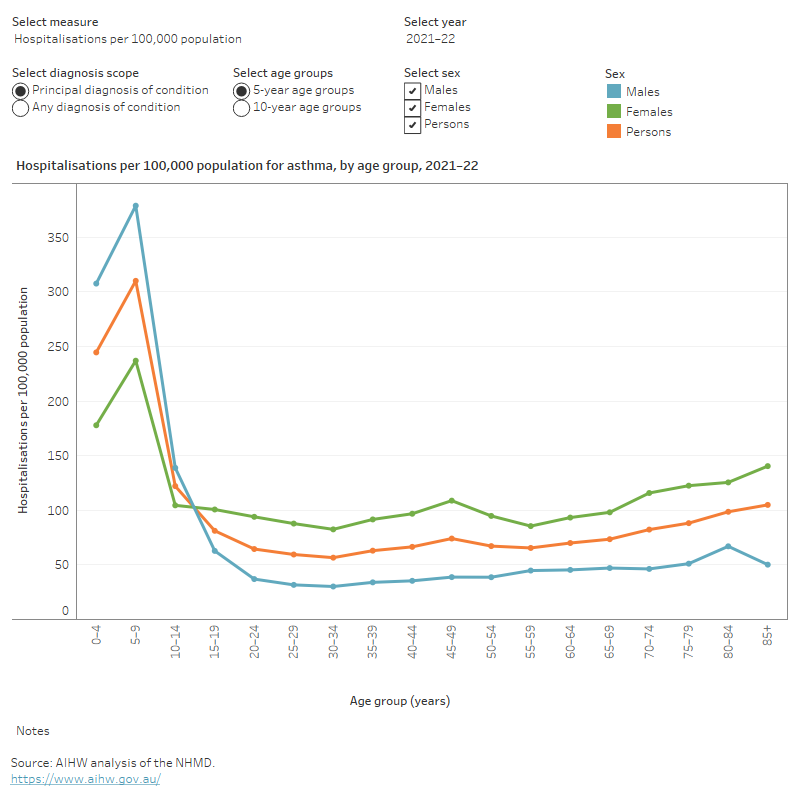

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, most of the 25,500 hospitalisations for a principal diagnosis of asthma in Australia were for children and young people aged 0–19 (Figure 15). The age profile of hospitalisations for asthma was much younger compared with hospitalisations for all causes in the same year. In 2021–22:

- the hospitalisation rate among children aged 0–14 was markedly higher than the rate among people aged 15 and over (225 and 70 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- boys aged 0–14 were 1.6 times as likely as girls of the same age to be admitted to hospital for asthma

- conversely, of those aged 15 and over, females were 2.4 times as likely as males to be admitted to hospital for asthma (Figure 15).

These differences in hospitalisation by age and sex reflect in part the difference in the prevalence of asthma—which tends to be more common in boys compared with girls for those aged under 15, and generally more common in females compared with males for those aged over 25.

Figure 15: Age distribution for asthma hospitalisations, by sex, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that asthma hospitalisation rates were highest for children aged 5–9 and lowest for people aged 30–34.

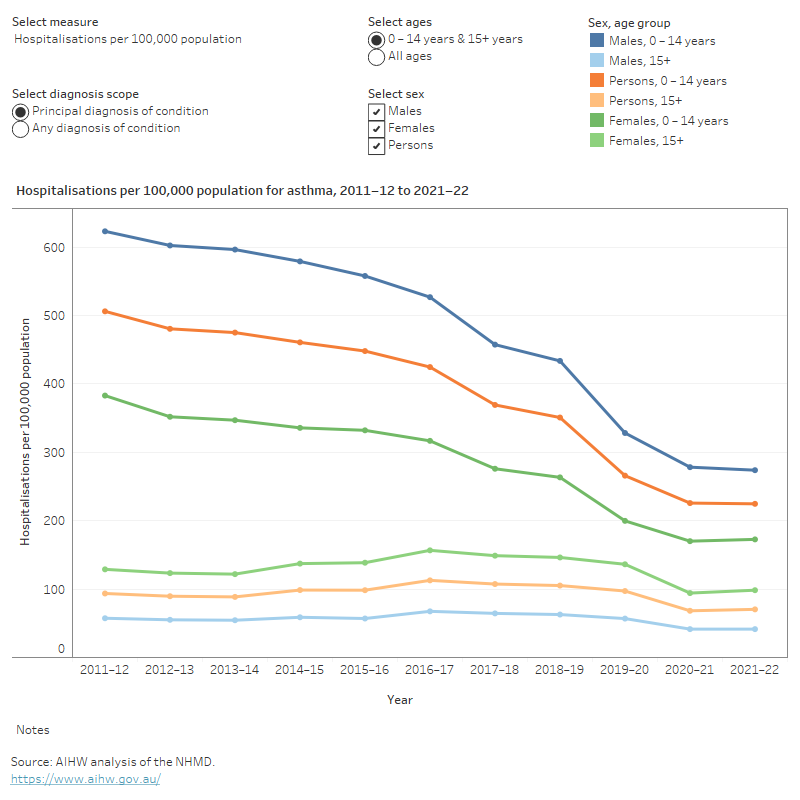

Trends over time

From 2011–12 to 2021–22:

- the rate of hospitalisations for children aged 0–14 decreased overall, from 510 to 225 per 100,000 population

- the proportion of overnight hospitalisations for children aged 0–14 decreased from 77% to 62%, while the average length of overnight stays remained relatively stable over the period, and was 1.6 days in 2021–22

- for those aged 15 and over, the rate of hospitalisations for asthma was relatively stable (between 68 and 115 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- for those aged 15 and over, the proportion of overnight stays trended down from 77% to 63%, and the average length of overnight stays remained stable (3.5 to 3.3 bed days) (Figure 16).

The rate of hospitalisations over the past few years has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information on this, see the Chronic respiratory conditions COVID-19 impact section.

Figure 16: Trends over time for asthma hospitalisations, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that asthma hospitalisations for males aged 0–14 were higher compared with females of the same age between 2011–12 to 2021–22.

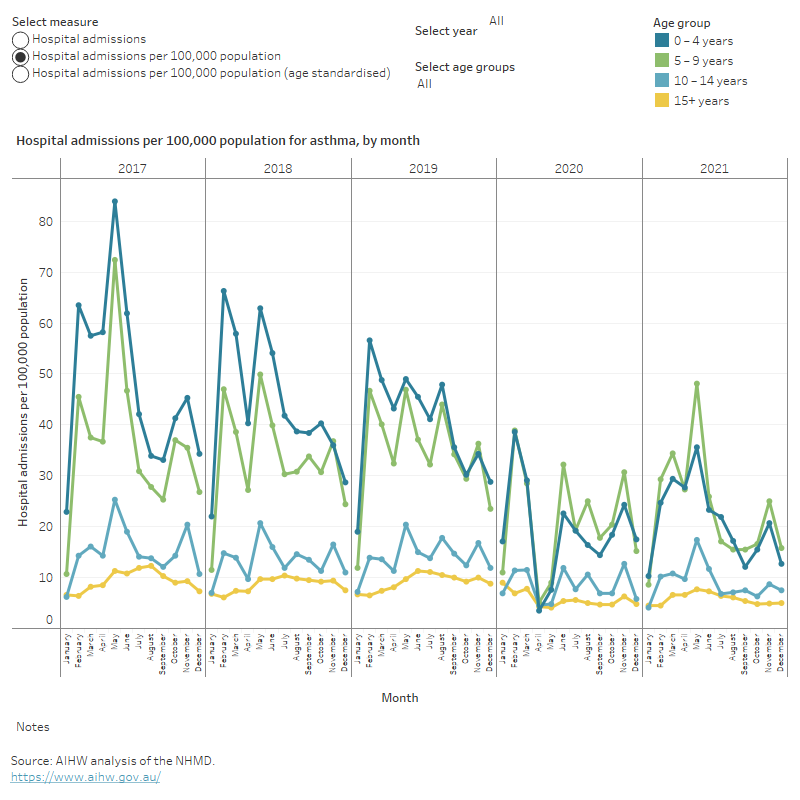

Seasonal variation in hospitalisations for asthma

Among children, the peaks for asthma hospitalisations occur in late summer (February) and autumn (May) (Figure 17). The peak in February is likely related to respiratory infections associated with returns to school and childcare after the summer break. Similar peaks are observed in September in Northern Hemisphere countries; lower use of preventer medication during holidays may also contribute.

2020 was an exception to this general trend, and there was a large dip in hospitalisations in April and May for all age groups (Figure 17). This is likely due to lockdown mandates across the nation related to COVID-19. For more on the impact of COVID-19 see the Chronic respiratory conditions COVID-19 impact section.

Asthma hospitalisations can also be impacted by one-off natural events which occur on a seasonal basis, such as thunderstorms and bushfires (See section on ‘Impact of natural events on asthma’ in ‘What causes asthma section’ for more details).

Figure 17: Monthly variation in hospitalisations due to asthma, by age group, 2017 to 2021

This figure shows that asthma hospitalisations increased most in children aged 0–4 from January to May 2017 (23 to 84 per 100,000 population).

Hospitalisations by Primary Health Care Network

In 2020–21, the 3 PHN areas with the highest rates of hospitalisations were: Western Queensland (QLD), Northern Territory (NT), and Darling Downs and West Moreton (QLD) (245, 200 and 170 per 100,000 population, respectively), after adjusting for age.

The 3 PHN areas with the lowest hospitalisation rates were: Perth North (WA), Perth South (WA), and South Eastern NSW (NSW) (54, 54, and 59 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Hospitalisations for asthma per 100,000 population by Primary Health Network areas, age standardised rate, 2020–21

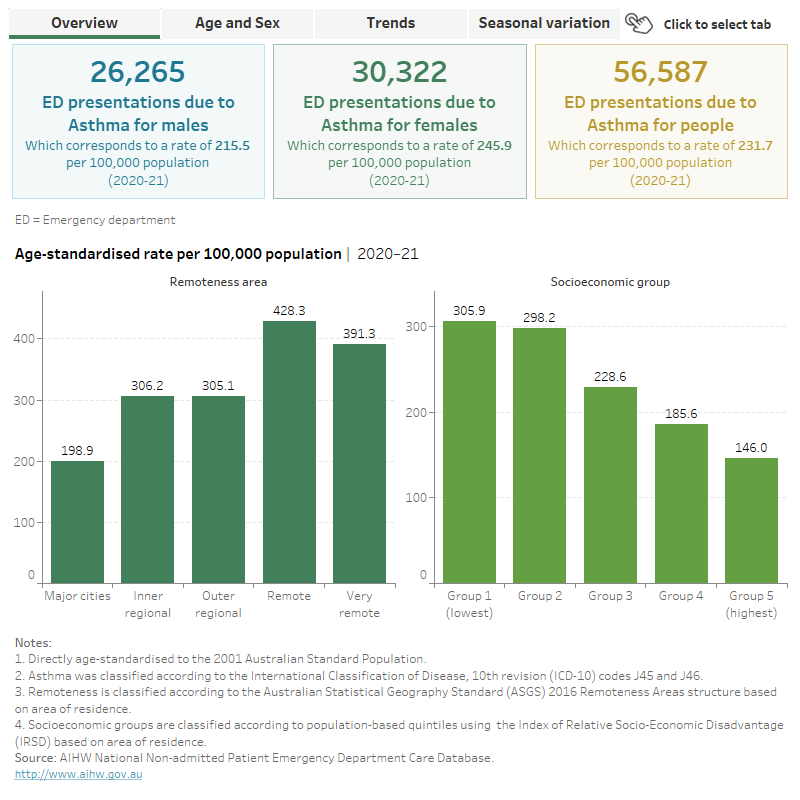

Emergency department presentations for asthma

National asthma indicator 10: The number of emergency department presentations where asthma was the principal diagnosis, per 100,000 population (age-standardised)

Data from the National Non-Admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database (NAPEDC) show that in 2020–21:

- there were 56,600 emergency department (ED) presentations for asthma, about 230 presentations per 100,000 population

- ED presentation rates were higher for females compared with males overall (245 and 215 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- boys aged 0–14 were 1.6 times as likely as girls of the same age to present to the emergency department for asthma (Figure 19).

Between 2018–19 and 2020–21, ED presentation rates decreased from 300 to 230 per 100,000 population and were higher for females compared with males.

Seasonal variation was also noted for asthma ED presentation rates though this has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020 (for COVID-19 pandemic timelines see ABS 2021):

- In 2019, rates were relatively high between March and August (24 to 29 per 100,000 population per month).

- From March to May 2020 ED presentation rates more than halved (from 26 to 11 per 100,000 population, respectively). This decrease is likely due to the nationwide lockdown which began on 23 March related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- ED presentations rose slightly from May 2020, when COVID-19 restrictions began to ease (Figure 19).

In 2020–21, ED presentations rates were:

- highest for people living in Remote areas and the lowest was reported for those living in Major cities (430 and 200 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (305 and 145 per 100,000 population) (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Emergency department presentations due to asthma, by age and sex, remoteness area and socioeconomic group, by month, 2018–19 to 2020–21

This figure shows that in 2020–21, asthma emergency department presentation rates were highest for children aged 0–14 and lowest for people aged 65–74.

Comorbidities of asthma

Some people with asthma have other long-term conditions, known as ‘comorbidity’. For people with asthma, having a comorbid chronic condition can have important implications for their health outcomes, quality of life and treatment choices.

This asthma comorbidity analysis included arthritis, back problems, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart, stroke and vascular disease, kidney disease, mental and behavioural conditions and osteoporosis or osteopenia. These 9 chronic conditions have been selected because they are common in the general community, pose significant health problems, have been the focus of ongoing national surveillance efforts, and action can be taken to prevent their occurrence (ABS 2022b).

According to the NHS, in 2020–21, around 914,000 (78%) people aged 45 and over, who currently have asthma, also reported having one or more of the 9 selected chronic conditions (Figure 20).

Types of comorbid chronic conditions in people with asthma

In 2020–21, among people aged 45 and over with asthma:

- 42% had arthritis (compared with 26% among people without asthma)

- 33% had back problems (compared with 23% among people without asthma)

- 31% had heart, stroke, and vascular disease (compared with 22% among people without asthma)

- 20% had mental and behavioural conditions (compared with 11% among people without asthma)

- 14% had COPD (compared with 1.9% among people without asthma)

- 13% had osteoporosis or osteopenia (compared with 7.6% among people without asthma) (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Comorbidity and prevalence of selected chronic conditions in people aged 45 and over with and without asthma, 2020–21

This figure shows that 47% of people aged 45 and over with asthma had 2 or more other chronic conditions.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19, ABS Cat. no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS, accessed 9 March 2023.

ABS (2021) Impact of lockdowns on household consumption – insights from alternative data sources, accessed 28 February 2023.

ABS (2022a) Asthma 2020–2021, accessed 9 February 2023.

ABS (2022b) 2020–21 NHS: First Results methodology, accessed 10 March 2023.

ACAM (Australian Centre for Asthma Monitoring) (2011) Asthma in Australia 2011, AIHW Asthma Series no. 4. Cat. no. ACM 22, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 3 February 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2018) Australia's health 2018, Chapter 4 Determinants of Health,Australia's health series no. 16. Cat. no. AUS 221, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 3 February 2023.

AIHW (2021a) Data update: Short-term health impacts of the 2019–20 Australian bushfires, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 15 March 2022.

AIHW (2021b) Chronic health conditions among culturally and linguistically diverse Australians, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 9 March 2023.

AIHW (2021c) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 May 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023. doi:10.25816/e2v0-gp02.

AIHW (2022b) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, Indicator 1.04 Respiratory disease (data table D1.04.1)/ Data – AIHW Indigenous HPF, accessed 17 February 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023c) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023d) First Nations people with asthma, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 17 October 2023.

Asthma Australia (2022) Asthma Guidelines for Australian Schools, accessed 27 April 2023.

Australian Indigenous HealthinfoNet (2018) Summary of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health Status, accessed 11 July 2023.

Britt H, Miller GC, Bayram C, Henderson J, Valenti L, Harrison C, Pan Y, Charles J, Pollack AJ, Wong C and Gordon J (2016) ‘General practice activity in Australia 2015–16’, General practice series no. 40. Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Deloitte Access Economics (2015) The Hidden Cost of Asthma: Asthma Australia and National Asthma Council Australia, accessed 27 April 2023.

Dharmage SC, Perret JL and Custovic A (2019) ‘Epidemiology and asthma in children and adults’, Frontiers in Pediatrics, 7:246.

DoHAC:TGA (Department of Health and Aged Care: Therapeutic Goods Administration) (2020), COVID-19 limits on dispensing and sales at pharmacies, accessed 9 March 2023.

GINA (Global Initiative for Asthma) (2019), Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention (for adults and children older than 5 years), accessed 9 March 2023.

Liu JC, Pereira G, Uhl SA, Bravo MA and Bell ML (2015) ‘A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke’, Environmental Research, 136:120–132, doi:10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.015.

NACA (National Asthma Council Australia) (2018) National Asthma Strategy, National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne, accessed 9 March 2023.

NACA (2019) Thunderstorm asthma, National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne, accessed 9 February 2023.

NACA (2022) Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 2.2. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne, accessed 3 March 2023.

Parliament of Australia (2020) 2019–20 bushfires—frequently asked questions: a quick guide, Parliament of Australia, Australian Government, accessed 9 March 2023.

PSA (Pharmaceutical Society of Australia) (2022) COVID-19 information for pharmacists, accessed 9 March 2023.

RACGP (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) (2022), Upcoming MBS changes GPs need to know, accessed 27 April 2023.

Stanford Children’s Health (2020) Management and Treatment of Asthma: Stanford Children’s Health, California, accessed 10 February 2023.

Thien F, Beggs PJ, Csutoros D, Darvall J, Hew M, Davies JM, Bardin PG, Bannister T, Barnes S, Bellomo R, Byrne T, Casamento A, Conron M, Cross A, Crosswell A, Douglass JA, Durie M, Dyett J, Ebert E, Erbas B and French C (2018) ‘The Melbourne epidemic thunderstorm asthma event 2016: an investigation of environmental triggers, effect on health services, and patient risk factors’, Lancet Planet Health, 2(6):e255–e263, doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30120-7.

Victoria State Government (2022) Epidemic thunderstorm asthma forecast, Victoria State Government, accessed 9 March 2023.

Wakefield MA, Coomber K, Durkin SJ, Scollo M, Bayly M, Spittal MJ, Simpson JA and Hill D (2014) ‘Time series analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence among Australian adults, 2001–2011’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92:413-22.

WHO (World Health Organisation) (2017) Asthma, WHO, Geneva, accessed 5 February 2023.