Engagement in education

School students with disability

In 2018, 1 in 10 (10%) school students aged 5–18 had disability.

Type of school attended

In 2018, 9 in 10 (89%) school students aged 5–18 with disability went to a mainstream school and 12% went to a special school.

Studying for non-school qualification

In 2018, 9.1% of people aged 15–64 with disability were studying for a non-school qualification (15% without disability).

On this page:

Introduction

In 2018, an estimated 380,000 children aged 5–18 with disability attended primary or secondary school and 187,000 people aged 15–64 with disability were studying for a non-school qualification (ABS 2019).

While people with disability attend school at a similar rate to those without disability, they are less likely to be studying for a non-school qualification.

Data note

Data on this page are largely sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics' (ABS) 2018 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC). For more information about the SDAC, including the concepts of disability, disability severity, disability groups, and remoteness categories used by the SDAC, see ‘Data sources’.

Unless otherwise indicated, all data on this page refer to 2018.

Early childhood education

In 2022, children with disability made up 6.3% (or 14,000) of children enrolled in a preschool program in the year before full time schooling (children aged 4 and those aged 5 who were not repeating) (SCRGSP 2023).

Australia's Disability Strategy reporting

Preschool enrolment is one of the measures reported under the Australia's Disability Strategy Outcomes Framework. For more information, including trends and comparisons by state and territory, please see Preschool enrolment on Reporting on Australia's Disability Strategy 2021–2031 website.

In 2021, children with disability aged 0–5 made up 5.4% of children attending child care services approved by the Australian Government [children with disability in child care services are those who the service provider identifies as having continuing disability including intellectual, sensory or physical impairment] (SCRGSP 2023).

School (primary and secondary)

In 2018, an estimated 1 in 10 (10% or 380,000) school students in Australia had disability, and almost 1 in 18 (5.4% or 206,000) had severe or profound disability:

- 12% (or 227,000) of male students had disability, compared with 8.2% (or 154,000) of female students

- 12% (or 85,000) of students living in Inner regional areas had disability, compared with 9.3% (or 256,000) of students living in Major cities

- 2 in 3 (65% or 148,000) male school students with disability had intellectual disability, 40% (or 91,000) had psychosocial disability and 36% (or 81,000) had sensory and speech disability. This compares with 54% (or 84,000), 38% (or 58,000), and 26% (or 40,000) of female students respectively (ABS 2019).

What is meant by school, school-age and school student?

In this section:

- ‘School’ refers to primary and secondary school. School is compulsory in Australia between ages 6 and 16 (Services Australia 2023).

- ‘School-age children’ refers to people aged 5–18 living in households.

- ‘School students’ refers to people aged 5–18 living in households who attend primary or secondary school.

Almost all (89% or 380,000) school-age children with disability go to school, similar to children without disability (89% or 3.4 million) (Table ENGAGEMENT.1, ABS 2019).

There is no difference in school attendance between boys and girls with disability (both 90%, or 227,000 and 154,000 respectively) (ABS 2019). A small difference is evident by severity of disability (91% or 206,000 of those with severe or profound disability go to school, and 87% or 174,000 of those with other disability). There has been little change in this during 2003–2018 (Table ENGAGEMENT.1).

School-age children with psychosocial disability (13% or 23,000) are slightly more likely not to attend school than those with intellectual disability (8.7% or 22,000) (ABS 2019).

Disability status | 2003 | 2009 | 2012 | 2015 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

All with disability | 90.3 | 90.7 | 87.3 | 90.0 | 89.0 |

Severe or profound disability | 93.7 | 93.2 | 88.6 | 89.7 | 90.9 |

Other disability status | 87.7 | 88.2 | 86.1 | 89.7 | 87.4 |

Without disability | 88.3 | 88.4 | 88.2 | 90.4 | 89.2 |

Notes:

- Data are for people aged 5–18 living in households.

- ‘School’ includes primary and secondary school.

Source: ABS 2004, 2010, 2013, 2016b and 2019; see also Table ENGT2, Data tables – Engagement in education. View data tables

School sector

Data note

Data in this section are sourced from the 2021 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. For more information about HILDA, including the concepts of disability, disability severity, disability groups, and remoteness categories used by the HILDA Survey, see ‘Data sources’.

Schools in Australia belong to one of three sectors: government schools (also known as public or state schools), non-government Catholic schools, and other non-government (private, or independent) schools.

In 2021, more than three-quarters (76%) of people with disability aged 15–64 who went to school reported they attend, or have attended, government schools; 14% Catholic non-government schools; and 10% other non-government schools (DSS and MIAESR 2022). People with disability aged 15–64 (76%) were more likely to attend, or have attended, a government school than people without disability (67%). For people with disability, this varied by remoteness with government school being attended, or having been attended, by:

- 73% of people with disability living in Major cities

- 79% living in Inner regional areas

- 86% living in Outer regional, remote and very remote areas (DSS and MIAESR 2022).

This also varied by disability group. People aged 15–64 with intellectual disability (85%) were most likely to attend, or have attended, a government school while people with psychosocial disability (76%) were least likely. At the same time, people with severe or profound disability were about as likely (78%) to attend, or have attended, a government school as those with other disability status (75%) (DSS and MIAESR 2022).

Type of school or class

School students with disability generally attend either:

- special schools, which enrol only students who have disability or impairment, learning or socio-emotional difficulties, or are in custody, on remand or in hospital (ABS 2022)

- special classes within a mainstream school

- regular classes within a mainstream school, where students with disability may or may not receive additional assistance.

In 2018, most (89% or 338,000) school students with disability went to a mainstream school:

- 71% (or 269,000) attended only regular classes in a mainstream school

- 18% (or 67,000) attended special classes within a mainstream school (Table ENGAGEMENT.2).

The rest (12% or 45,000) went to a special school (Table ENGAGEMENT.2).

Type of school or class | Severe or profound disability | Other disability status | All with disability |

|---|---|---|---|

Special school | 19.7 | *2.3 | 11.9 |

Mainstream school only | 80.4 | 98.8 | 89.0 |

Special classes in a mainstream school | 21.4 | 13.4 | 17.7 |

Regular classes in a mainstream school only | 59.4 | 85.6 | 70.8 |

Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes:

* Relative standard error of 25–50% and should be used with caution.

- Data are for people with disability aged 5–18 living in households who attend primary or secondary school.

- Figures are rounded and components may not add to total because of ABS confidentiality and perturbation processes.

Source: ABS 2019; see also tables ENGT7 and ENGT8, Data tables – Engagement in education. View data tables

School students with severe or profound disability are less likely than other students with disability to go to a mainstream school and far more likely to go to a special school (Table ENGAGEMENT.2):

- 59% (or 122,000) attend regular classes in a mainstream school only, compared with 86% (or 149,000) with other disability status

- 21% (or 44,000) attend special classes within a mainstream school, compared with 13% (or 23,000) (ABS 2019).

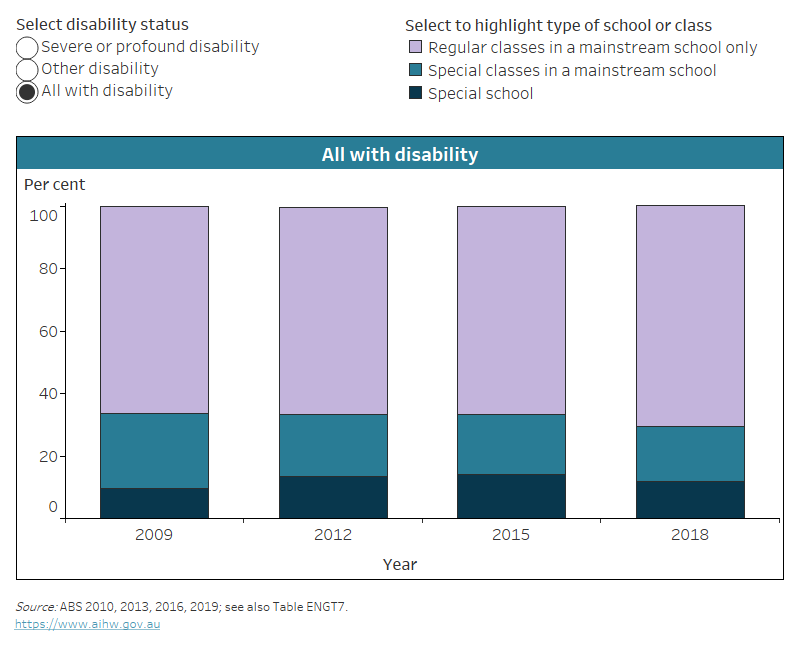

Recent years have seen little change in the proportion of students with disability attending special schools rather than mainstream schools (Figure ENGAGEMENT.1).

Figure ENGAGEMENT.1: Type of school or class attended by school students with disability, by severity of disability, 2009, 2012, 2015 and 2018

The chart shows that 71% of school students with disability in 2018 attended only regular classes in a mainstream school, compared with 66% in 2009.

Notes:

* Relative standard error of 25–50% and should be used with caution.

- Data are for people with disability aged 5–18 living in households who attend primary or secondary school.

- Figures are rounded and components may not add to total because of ABS confidentiality and perturbation processes.

Source data tables: Data tables – Engagement in education. View data tables

Interpreting changes in school attendance

Changing patterns in the type of school people with disability attend might reflect a mix of positive and negative experiences at student level.

Attendance at a special school might, for example, provide the most appropriate support for some students, but might also result in, or be the result of, increased segregation.

Likewise, attendance at mainstream schools could indicate that the education system has become better at integrating students with disability, fostering inclusion, and providing additional, tailored supports. Or it could be that resources are directing the placement of students into mainstream schools even if an appropriate level of support is not provided.

In addition, the increased number of students attending school with additional supports – such as through part-time attendance – might be a positive change if this reflects the most appropriate support (rather than lack of support), or if it enables attendance for someone who previously did not attend school.

Disability supports received by school students

Data note

Data in this section are sourced from the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability (NCCD). The NCCD includes information provided annually to the Australian Government Department of Education by both government and non-government schools.

The NCCD is primarily designed to collect information on the supports received by students with disability to help them participate in education. As such, it produces a support-based estimate of students with disability and is not intended to provide estimates of prevalence.

For more information, see NCCD.

In 2022, around 911,000 students received educational adjustments because of disability, or around 1 in 4 (23%) students (ACARA 2022).

Among students who received adjustments due to disability:

- most had cognitive disability (55% of students with disability who received adjustments), followed by social-emotional disability (32%), physical disability (10%) and sensory disability (2.9%)

- the levels of required adjustments were different, including

- adjustments of support within quality differentiated teaching practice (32%) – made infrequently or as low-level action. These may include minor adjustments to teaching and monitoring to meet safety requirements through usual school processes

- supplementary adjustments (43%) – for particular activities at specific times throughout the week. These may include adjustments to teaching, the provision of course materials in accessible forms, and programs to address the student's social/emotional needs

- substantial adjustments (17%) – made at most times on most days. These may include individualised instruction for most activities, and closely monitored playground supervision

- extensive adjustments (8.5%) – made at all times. These may include intensive instruction in a highly specialised manner for all activities, highly modified classroom environments, and extensive support from specialist staff (ACARA 2022).

Proportion of students receiving adjustments due to disability was higher for government schools (24% of students) compared with independent schools (22%) and Catholic schools (20%). Government schools also had a higher proportion of students who received ‘extensive’ or ‘substantial’ levels of adjustment than Catholic or independent schools – this was the case for 28% of students with disability at government schools who received adjustments, compared with 23% at Catholic schools and 18% at independent schools (ACARA 2022).

Non-school education

What is non-school education?

‘Non-school education’ refers to education other than pre-primary, primary or secondary education. It includes studying for qualifications at postgraduate degree level, master's degree level, graduate diploma and graduate certificate level, bachelor's degree level, advanced diploma and diploma level, and certificates I, II, III and IV levels. A student may study for a non-school qualification at the same time as a school qualification.

‘Non-school student’ is used in this section to refer to people aged 15–64 living in households who are studying for a non-school qualification.

Australia's Disability Strategy reporting

Participation in tertiary education is one of the priorities reported on under the Australia's Disability Strategy Outcomes Framework. Data on participation in Vocational Education and Training (VET) and on undergraduate participation are reported. For more information, including trends and comparisons by population groups, please see VET participation and Undergraduate participation on Reporting on Australia's Disability Strategy 2021–2031 website.

In 2018, around 1 in 12 (8.3% or 187,000) people aged 15–64 studying for a non-school qualification had disability. Very few (1.5% or 34,000) had severe or profound disability. This varied by type of educational institution. Of people aged 15–64:

- 6.3% (or 89,000) attending university or other higher education had disability; 1.2% (or 18,000) have severe or profound disability

- 11% (or 52,000) attending technical and further education (TAFE) or technical college had disability

- 13% (or 46,000) attending other educational institutions (such as business colleges or industry skills centres) had disability; 3.1% (or 11,000) have severe or profound disability (ABS 2019).

Overall, 1 in 11 (9.1% or 187,000) people with disability aged 15–64 are studying for a non-school qualification (ABS 2019). This is a lower proportion than for those without disability (15% or 2.1 million). Participation in non-school education by people with disability varies by remoteness, disability group, age and sex:

- 10% (or 138,000) of people with disability living in Major cities are studying for a non-school qualification compared with 6.6% (or 33,000) living in Inner regional areas

- people with psychosocial disability (9.8% or 63,000) are more likely to be studying for a non-school qualification than people with sensory and speech disability (5.5% or 23,000)

- females with disability (11% or 114,000) are more likely to be studying for a non-school qualification than males (7.5% or 76,000)

- people with disability aged 15–24 are nearly 4 times as likely (25% or 72,000) to be studying for a non-school qualification as people aged 25–64 (6.5% or 115,000) (ABS 2019).

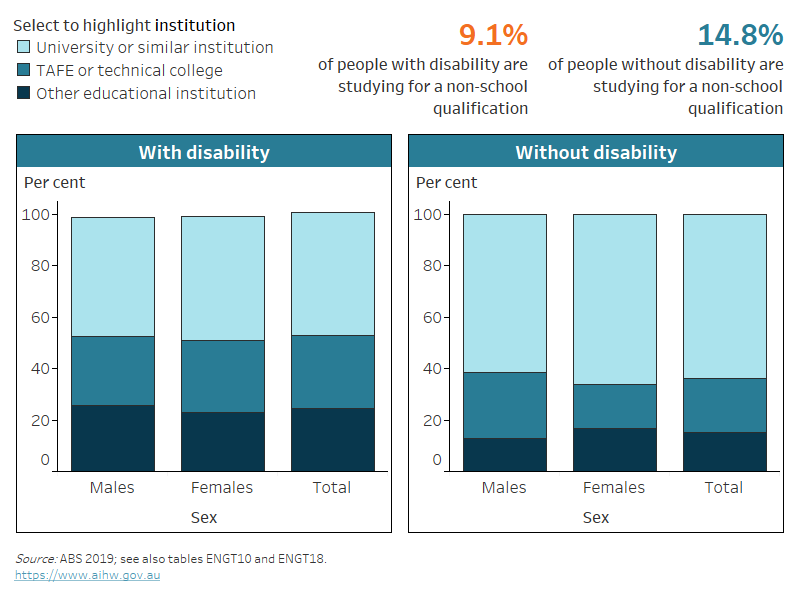

When people with disability study for a non-school qualification, they are more likely to do so at a university or other higher education institution (48%) than at a TAFE or technical college (28%) or at other types of educational institutions (25%) (ABS 2019).

However, non-school students with disability are less likely to study at a university than those without disability – 48% attend a university or other higher education institution, compared with 64% without disability (Figure ENGAGEMENT.2). Non-school students with disability are more likely than those without disability to attend a TAFE or technical college (28% compared with 21%); and to attend other educational institutions (25% compared with 15%) (Figure ENGAGEMENT.2).

Recent years have seen little change in the proportions of students with disability among those attending non-school educational institutions (Table ENGAGEMENT.3).

Figure ENGAGEMENT.2: Type of educational institution attended by people studying for a non-school qualification, by disability status and sex, 2018

The chart shows that lower proportions of both males and females with disability attend a university or similar than among those without disability.

Note: Data are for people aged 15–64 living in households who currently study for a non-school qualification.

Source data tables: Data tables – Engagement in education. View data tables

Type of educational institution | 2003 | 2009 | 2012 | 2015 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

University or other higher education | 8.1 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 6.3 |

TAFE or technical college | 11.9 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 11.9 | 10.8 |

Other educational institution | 11.8 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 12.9 | 12.9 |

Notes:

- Data are for people aged 15–64 living in households who currently study for a non-school qualification.

- ‘Other educational institution’ includes non-school qualifications completed through a secondary school, business college, industry skills centre or other educational institution.

Source: ABS 2019; see also Table ENGT20, Data tables – Engagement in education. View data tables

Experiences of people with disability studying for a non-school qualification

Data note

Data in this section are sourced from the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) Total Vocational Education and Training (VET) Students and Courses Collection, and the Department of Education's Higher Education Student Data Collection, Student Experience Survey, and Graduate Outcomes Survey.

These sources define disability differently from each other and from the ABS SDAC. They also rely on self-disclosure of disability. Because of this, figures vary between sources.

This section uses the most recent data available at the time of writing this report. More recent data has become available shortly before release of this report, however publication timelines did not permit its inclusion.

Vocational education and training

VET participation

In 2022, 4.1% of domestic VET students aged 15–64 self-identified as ‘having a disability, impairment or long-term condition’. For more information, including trends and comparisons by population groups, please see VET participation on Reporting on Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021–2031 website.

The Total VET Students and Courses 2022 collection indicates that 3.9% (or 172,000) of VET students aged 15–64 self-identified as having disability, impairment or long-term health condition; 85% (or 3.7 million) identified as not having disability and for 11% (or 497,000) disability status was recorded as not known (NCVER 2023).

Private training providers were the most common provider type for VET students with and without disability. However, in 2022, VET students with disability aged 15–64 were:

- less likely to attend a private training provider (60% or 102,000) than those without disability (78% or 2.9 million)

- more likely to attend a government-funded Technical and Further Education (TAFE) provider (31% or 53,800 compared with 16% or 601,000) (NCVER 2023).

VET students with disability were also:

- about as likely to be full-time students (13% or 21,500) as those without disability (11% or 403,000)

- more likely to be attending school while completing their VET course (14% or 22,600) than those without disability (8.6% or 301,000) (for those with known school status)

- slightly less likely to have successfully completed some post-secondary education before their VET studies (57% or 93,800) than those without disability (61% or 2.2 million) (for those with known prior education status)

- less likely to have attained a bachelor’s degree (12% or 19,500) as their prior highest level of educational attainment than those without disability (23% or 805,000) (for those with known educational attainment)

- more likely to have left school after Year 10 and not yet pursued further study before their VET studies (16% or 26,000) than those without disability (8.9% or 311,000)

- less likely to be in the labour force (employed or unemployed) (84% or 132,000) than those without disability (94% or 3.1 million) (for those with known labour force status)

- less likely to be employed (57% or 89,900) than those without disability (83% or 2.7 million) (NCVER 2023).

Higher education

Undergraduate participation

In 2021, 10% of domestic undergraduate higher education students aged 15 and over self-identified as ‘having a disability, impairment or long-term condition’. For more information, including trends and comparisons by population groups, please see Undergraduate participation on Reporting on Australia's Disability Strategy 2021–2031.

In the Higher Education Student Data Collection (HESC), students self-identify as having disability by indicating that they have ‘disability, impairment or long-term medical condition which may affect their studies’. In 2021, 9.4% (or 108,000) of domestic higher education students (both undergraduate and graduate) self-identified as having disability:

- students who identified as having disability were more likely (3.6% or 3,940) to also identify as First Nations (Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander) people than those who did not identify as having disability (1.9% or 20,000)

- the proportion of students who identified as having disability has steadily increased from 4.0% in 2006 to 5.5% in 2014 and 9.4% in 2021 (Department of Education 2023).

According to the 2022 Student Experience Survey (SES), students with disability currently undertaking studies in Australian higher education institutions were:

- less likely than those without disability to give a positive rating to the quality of their entire educational experience

- 74% compared with 76%, for students in undergraduate courses

- 71% compared with 77%, for students in postgraduate coursework courses

- more likely than those without disability to consider early departure from their course

- 26% compared with 18%, for students in undergraduate courses

- 30% compared with 17%, for students in postgraduate coursework courses (QILT 2023a).

In 2022, 9.7% (or 16,000) of the undergraduate students who completed the SES reported having disability, as did 6.3% (or 4,400) of the postgraduate coursework students (QILT 2023a).

The 2022 Graduate Outcomes Survey data show that recent graduates of Australian higher education institutions who reported they had disability were less likely than those without disability to be satisfied with various aspects of their studies, including:

- for undergraduate courses – their course overall (74% of graduates who reported disability compared with 78% of those without disability)

- for postgraduate coursework courses – their course overall (77% compared with 80%)

- for postgraduate research courses – their course overall (80% compared with 87%), and with specific aspects such as intellectual climate (53% compared with 64%), skills development (90% compared with 94%), infrastructure (69% compared with 79%), thesis examination (78% compared with 84%), and industry engagement (49% compared with 58%) (QILT 2023b).

Non-disclosure of disability

Not all students with disability choose to disclose their disability.

One survey of 1,100 students (including 253 students with disability) on non-disclosure of equity group status in Australian universities estimated that 11% did not disclose their equity status to their university. Of students who did not disclose their equity status, 11% of students with disability did not disclose their disability to their university (Clark et al. 2018).

Students with disability may trust in the university and believe that disclosure is of benefit to them. Students with disability may also fear prejudice at the university, such as being labelled as less competent or deserving of their academic success. Students with disability also may not believe the university needs the information or do not know why they should disclose.

The survey also found that students with disability are more likely to disclose to a support service than to an admissions centre or on enrolment. The survey suggested that students are motivated to disclose if they feel they need to access supports, and may not know if they need such support until after they have started studying.

Where can I find out more?

- Data tables for this report.

- ABS Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018.

- Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability (NCCD).

- Department of Education – Higher Education Statistics.

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching.

- National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2004) Microdata: disability, ageing and carers, Australia, 2003, ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder data, accessed 14 September 2020.

ABS (2010) Microdata: disability, ageing and carers, Australia, 2009, ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder data, accessed 14 September 2020.

ABS (2013) Microdata: disability, ageing and carers, Australia, 2012, ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder data, accessed 14 September 2020.

ABS (2016) Microdata: disability, ageing and carers, Australia, 2015, ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder data, accessed 23 November 2021.

ABS (2019) Microdata: disability, ageing and carers, Australia, 2018, ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder data, accessed 14 September 2020.

ABS (2022) Schools methodology, ABS, accessed 27 October 2023.

ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) (2022) National report on schooling in Australia: School students with disability, ACARA website, accessed 18 July 2023.

Clark C, Wilkinson M and Kusevskis-Hayes R (2018) Enhancing self-disclosure of equity group membership, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Department of Education (2023) Selected higher education statistics – 2021 student data: section 11 – equity groups [data set], Department of Education, Australian Government, accessed 18 July 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) and MIAESR (Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic & Social Research) (2022) The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, General Release 21, wave 21, doi:10.26193/KXNEBO, ADA Dataverse, V3, AIHW analysis of unit record data, accessed 7 December 2022.

NCVER (National Centre for Vocational Education Research) (2023) Total VET students and courses 2022: students, AIHW analysis of DataBuilder data, accessed 21 August 2023.

QILT (Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching) (2023a) 2022 Student Experience Survey, QILT, accessed 18 July 2023.

QILT (2023b) 2022 Graduate Outcomes Survey, QILT, accessed 19 July 2023.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) (2023) Report on Government Services 2023: vol B, Child care, education and training, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 27 June 2023.

Services Australia (2023) School years, Services Australia website, accessed 1 August 2023.