Clients with a current mental health issue

On this page

Mental health is fundamental to the wellbeing of individuals, their families and the population as a whole (ABS 2018). According to the most recent national Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, in 2007, 1 in 5 (20%) Australians (aged 16–85) had a current mental health issue, while 45% of Australians reported having had a mental disorder at some point in their life (ABS 2008). More recent research has indicated that around 1 in 8 (13%) Australians experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress (ABS 2018). The intertwined nature of mental health issues and homelessness is well established (Kalevald et al. 2018). People with mental health issues are a group who are particularly vulnerable to homelessness. Research has shown that experiences of homelessness can trigger, exacerbate and magnify mental health issues (see for example, Kalevald et al. 2018, Brackertz et al 2018, CHP 2018 and Johnson & Chamberlain 2011). People living with a mental illness can be isolated, have disrupted family and social networks and sometimes suffer poor physical health, all of which impact their capacity to find and maintain adequate housing. Further, symptoms such as hallucinations, compulsive behaviours and anxiety can make it difficult to seek and maintain employment, which has financial impacts (Robinson 2003).

People experiencing homelessness with mental health issues need the support of various services including services dedicated to finding housing solutions, but navigating through these services can be particularly challenging. Several studies suggest that when people with mental health issues are supported by homelessness agencies, they are more likely to remain housed rather than become homeless (MHCA 2009, Du et al. 2013, Wood et al. 2016, ABS 2014).

Reporting clients with a mental health issue in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) clients are identified as having a current mental health issue if they are aged 10 years or older and have provided any of the following information:

- They indicated that at the beginning of support they were receiving services or assistance for their mental health issues or had in the last 12 months.

- Their formal referral source to the SHS was a mental health service.

- They reported ‘mental health issues’ as a reason for seeking assistance.

- Their dwelling type either a week before presenting to an agency, or when presenting to an agency, was a psychiatric hospital or unit.

- They had been in a psychiatric hospital or unit in the last 12 months.

- At some stage during their support period, a need was identified for psychological services, psychiatric services or mental health services.

Key findings

- In 2019–20, there were 88,300 SHS clients reporting a current mental health issue, an increase of 1,800 clients from the previous year.

- Clients with a current mental health issue were one of the largest SHS client groups (30% of all SHS clients) as well as one of the fastest growing client groups (increasing from 30.3 per 10,000 population in 2015–16 to 34.8 per 10,000 population in 2019–20).

- Over half of all SHS clients with a current mental health issue were known to be housed, but at risk of homelessness (50%) when they sought SHS support, and most were returning clients (68%), having previously been assisted by a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12.

- It was more common for clients with a current mental health issue to present to SHS agencies alone (80%) than in family units or groups.

- At the end of SHS support, fewer clients with a current mental health issue were homeless (37%, down from 49%); with 3,400 fewer clients sleeping rough (decreasing from 7,500 to almost 4,100 clients).

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is posing significant health, lifestyle and economic challenges for Australians and evidence shows there is likely to be a significant negative mental health impact as a result (NMHC 2020). Common consequences of disease outbreaks include anxiety and panic, depression, anger, confusion and uncertainty, and financial stress (Black Dog Institute 2020).

COVID-19 has led to an increase in many of the risk factors for poor mental health including uncertainty, the risk of ill health, job loss and social isolation (Edwards et al. 2020). People with pre-existing anxiety or other mental health disorders are particularly vulnerable and at risk of experiencing higher anxiety levels during the COVID-19 outbreak, they may require more support or access to mental health treatment during this period (Black Dog Institute 2020). This report presents data for the financial year up to 30 June 2020, which overlaps with the beginning few months of the Australian spread of COVID-19. Therefore, any changes to the proportion of clients receiving SHS support with mental health issues may not be evident in the following data.

Client characteristics

Of the 290,500 SHS clients accessing services in 2019–20, 88,300 (30%) clients reported a current mental health issue. The number and proportion of clients with a current mental health issue has been increasing since the beginning of the SHSC in 2011–12. Various factors, including increased identification, community awareness and reduced stigma, may have had an impact on the increase in self-identification and reporting of mental illness among SHS clients. In 2019–20 (Table MH.1):

- Clients with a current mental health issue were one of the fastest growing client groups within the SHSC, growing by 22% since 2015–16. Between 2018–19 and 2019–20 the increase was 2%, a smaller increase than in the previous period (7% between 2017–18 and 2018–19).

- The rate of clients with a current mental health issue has remained stable between 2018–19 and 2019–20 at 35 clients per 10,000 population but has increased from 30.3 in 2015–16.

|

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of clients |

72,120 |

77,286 |

81,004 |

86,499 |

88,338 |

|

Proportion of all clients |

26 |

27 |

28 |

30 |

30 |

|

Rate (per 10,000 population) |

30.3 |

31.9 |

32.9 |

34.6 |

34.8 |

Notes:

- Rates are crude rates based on the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June of the reference year. Minor adjustments in rates may occur between publications reflecting revision of the estimated resident population by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Data for 2015–16 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2015–16 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Age and sex

In 2019–20, of those clients presenting with a current mental health issue (Supplementary table MH.1):

- There were more female (more than 53,900 clients or 61%) than male SHS clients (almost 34,400 or 39%), similar to the proportions in 2018–19 (60% and 40% respectively).

- Almost half (45% or 24,100 clients) of females were aged between 18 and 34 years, higher than the proportion of males in the same age group, 37% or almost 12,700 clients.

- Clients aged 18–24 increased 5% (or almost 900 clients) between 2018–19 and 2019–20 with females as the largest contributor to this increase.

Indigenous clients

In 2019–20, around 85,400 SHS clients with a current mental health issue reported their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status (Supplementary table MH.8). Key findings for this group include:

- 1 in 5 (20% or 17,200 clients) were Indigenous.

- Almost 2 in 3 (65% or 11,100) Indigenous clients with a current mental health issue were female, and 35% (6,100 clients) were male.

- Around 4 in 10 (38% or 6,500) Indigenous SHS clients with a current mental health issue were aged 10–24 years, a further 45% (7,700 clients) were aged 25–44 and 17% (almost 3,000 clients) were aged over 45.

State and territory

There were differences across the states and territories in the rates of SHS clients with a current mental health issue. In 2019–20:

- SHS agencies based in Victoria had the greatest number of clients (35,200 clients) and the second highest rate of clients with a current mental health issue (53 clients per 10,000 population). Tasmania had the highest rate, with 61 clients per 10,000 population (Supplementary table MH.2).

- Over half (51% or 3,300) of Tasmania’s SHS clients reported a current mental health issue, along with 42% (over 1,700) of clients in the Australian Capital Territory and 36% (almost 25,400) in New South Wales. By contrast, 10% (1,100) of the SHS clients in the Northern Territory reported a current mental health issue (Supplementary tables MH.2 and CLIENTS.1).

Living arrangements and presenting unit type

In 2019–20 at the beginning of support, clients with a current mental health issue (aged over 10) were more likely be living alone (39,800 clients or 46%) or as a lone parent with child(ren) (19,700 clients or 23%) rather than in a group (6,900 clients or 8%) or as a couple without child(ren) (4,600 or 5%) (Supplementary table MH.10).

SHS clients with a current mental health issue were also more likely to present to a SHS agency alone (80% or 70,500 clients) compared with all SHS clients (61% or 178,500) (Supplementary table MH.9 and CLIENTS.9).

Selected vulnerabilities

In 2019–20, of the 88,300 SHS clients who had a current mental health issue, over half (55% or 48,200 clients) were experiencing additional selected vulnerabilities (Table MH.2):

- 4 in 10 clients (41% or 35,800 clients) also experienced family and domestic violence.

- 24% (21,100 clients) of clients also reported problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

- A further 1 in 10 (10% or almost 8,700 clients) experienced all 3 selected vulnerabilities: family and domestic violence, problematic drug and/or alcohol use and a current mental health issue.

These figures provide an insight into the multiple disadvantages clients experiencing mental health issues face and highlight the value of an integrated service response to homelessness for these clients (Flatau et al. 2013).

|

Family and domestic violence |

Mental health issue |

Problematic drug and |

Clients |

Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8,684 |

9.8 |

|

Yes |

Yes |

No |

27,099 |

30.7 |

|

No |

Yes |

Yes |

12,435 |

14.1 |

|

No |

Yes |

No |

40,120 |

45.4 |

|

|

|

|

88,338 |

100.0 |

Notes:

-

Clients are assigned to one category only based on their vulnerability profile.

-

Clients are aged 10 and over.

-

Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2019–20.

Housing situation on first presentation

At the beginning of their first support period in 2019–20, 1 in 2 (50%) SHS clients who had a current mental health issue were experiencing homelessness when they first presented to a SHS agency while 50% were at risk of homelessness (Supplementary table CLIENTS.12).

Service use patterns

Service use patterns for clients with a current mental health issue have changed between 2015–16 and 2019–20 (Table MH.3).

- There was an increase in the median number of days of support, from 64 days in 2015–16 to 75 days in 2019–20.

- The proportion of clients receiving accommodation decreased (from 39% to 37%), along with the median number of nights accommodated (from 44 to 39 nights per client).

|

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Length of support (median number of days) |

64 |

68 |

72 |

75 |

75 |

|

Average number of support periods per client |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

|

Proportion receiving accommodation |

39 |

37 |

37 |

36 |

37 |

|

Median number of nights accommodated |

44 |

45 |

43 |

39 |

39 |

Notes:

- The denominator for the proportion receiving accommodation is all SHS clients who have a current mental health issue. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

- Data for 2015–16 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2015–16 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2015–16 to 2019–20.

New or returning clients

In 2019–20, of those SHS clients with a current mental health issue (Supplementary table MH.7):

- Most (68% or nearly 59,700 clients) were returning clients, that is, they had previously received assistance from a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12.

- One-third (32% or almost 28,700 clients) of those with a current mental health issue were new to SHS agencies, having not previously received services.

Main reason for seeking assistance

In 2019–20, the most common main reasons for seeking SHS assistance for clients with a current mental health issue were (Supplementary tables MH.5 and MH.6):

- family and domestic violence (20% or 17,600 clients)

- housing crisis (20% or more than 17,400 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (13% or almost 11,600 clients).

There were differences in the main reasons for those clients with a current mental health issue presenting at risk of, or experiencing homelessness:

- For clients at risk of homelessness, family and domestic violence (25% or 10,600 clients) was the most common main reason, followed by housing crisis (17% or 7,200 clients).

- For clients experiencing homelessness, housing crisis (24% or almost 10,000) was the most common main reason, followed by inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (19% or 8,100 clients).

Services needed and provided

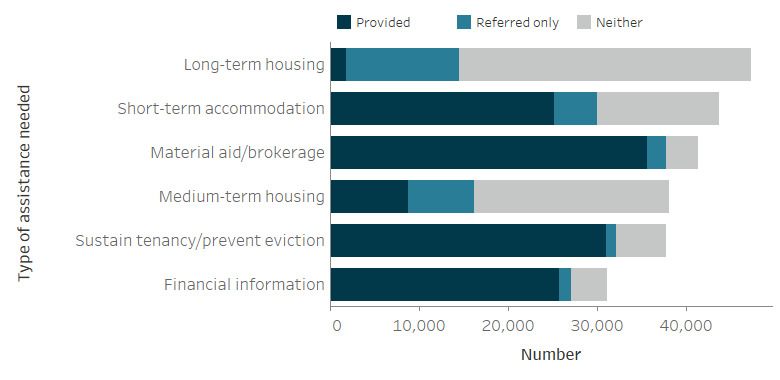

Figure MH.1 illustrates the top 6 most-needed services (excluding advice/information, other basic assistance or advocacy/liaison) for clients with a current mental health issue in 2019–20. Four of these were related to accommodation:

- long-term housing was the most needed service (47,300 clients or 54%) yet least provided (4% of these clients were provided this assistance). A further 12,700 clients (27%) in need of long-term housing were referred to another agency and over 32,800 (69%) clients in need were neither provided nor referred long-term housing.

- short-term or emergency accommodation was needed by nearly 43,700 clients (49%), with 6 in 10 (58% or 25,100) of these clients receiving this assistance.

- medium-term/transitional housing was needed by 38,100 clients (43%) and 23% (8,800) of these clients were provided this assistance. Similar to long-term housing, this type of accommodation was commonly referred (20% or over 7,400 clients).

- assistance to sustain tenancy/prevent eviction was needed by over 37,700 clients (43%) with a current mental health issue, and a comparatively high proportion were provided with this service (82% or 31,000 clients).

Over 1 in 4 (28% or 25,000) clients with a current mental health issue identified a need for mental health-based services (Supplementary tables MH.3). Specifically:

- 25% (22,000 clients) identified a need for mental health services with 44% (9,700 clients) of these requests met.

- 10% (over 9,100 clients) identified a need for psychological services with 32% (2,900 clients) of these requests met.

- 6% (5,400 clients) identified a need for psychiatric services with 35% (1,900 clients) of these requests met.

Figure MH.1: Clients with a current mental health issue, by most needed services and service provision status (top 6), 2019–20

Notes:

- Excludes 'Other basic assistance', 'Advice/information' and 'Advocacy/liaison on behalf of client'.

- 'Short-term accommodation' includes temporary and emergency accommodation and sustain tenancy/prevent eviction includes assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction.

- 'Neither' indicates a service was neither provided nor referred.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2019–20, Supplementary table MH.3.

The proportion of SHS clients with a current mental health issue with a case management plan has remained comparatively high over time (72% in 2019–20, up from 70% in 2015–16); however those achieving all case management goals has remained low (16% in 2019–20, down from 19% in 2018–19) (Supplementary table CLIENTS.35).

Outcomes at the end of support

Outcomes presented here describe the change in client’s housing situation between the start and end of support. Data is limited to clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year—meaning that their support periods had closed and they did not have ongoing support at the end of the year.

Many clients had long periods of support or even multiple support periods during 2019–20. They may have had a number of changes in their housing situation over the course of their support. These changes within the year are not reflected in the data presented here, rather the client situation at the start of their first support period in 2019–20 is compared with the end of their last support period in 2019–20. A proportion of these clients may have sought assistance prior to 2019–20, and may again in the future.

In 2019–20, for clients with a current mental health issue (Table MH.4):

- The proportion of clients known to be experiencing homelessness decreased from just under half (49%) at the start of support to 37% at the end of support; this equates to almost 7,700 fewer clients experiencing homelessness.

- While there was little change in the proportion of clients in short term temporary accommodation (around 17% at both the start and end), considerably fewer clients were ‘rough sleeping’ (from 13% to 8%) and ‘couch surfing’ (from 18% to 13%) following SHS support.

- One of the largest changes was the increase in the number of clients living in public or community housing (renter or rent free); increasing by over 3,600 clients (from 6,100 to 9,800 clients or 11% to 18%) from the start to the end of SHS support.

These trends demonstrate that by the end of SHS support, fewer clients with a current mental health issue were known to be experiencing homelessness, and most (63%) were living in stable accommodation, be it public or community, private or other housing or an institutional setting.

|

Housing situation |

Beginning of support |

End of |

Beginning of support |

End of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No shelter or improvised/inadequate dwelling |

7,483 |

4,070 |

13.2 |

7.5 |

|

Short term temporary accommodation |

9,826 |

9,151 |

17.4 |

17.0 |

|

House, townhouse or flat - couch surfer or with no tenure |

10,361 |

6,772 |

18.3 |

12.6 |

|

Total homeless |

27,670 |

19,993 |

49.0 |

37.1 |

|

Public or community housing - renter or rent free |

6,148 |

9,779 |

10.9 |

18.1 |

|

Private or other housing - renter, rent free or owner |

19,045 |

21,727 |

33.7 |

40.3 |

|

Institutional settings |

3,617 |

2,429 |

6.4 |

4.5 |

|

Total at risk |

28,810 |

33,935 |

51.0 |

62.9 |

|

Total clients with known housing situation |

56,480 |

53,928 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Not stated/other |

4,179 |

6,731 |

|

|

|

Total clients |

60,659 |

60,659 |

|

|

Notes:

- Percentages have been calculated using total number of clients as the denominator (less not stated/other).

- It is important to note that individual clients beginning support in one housing type need not necessarily be the same individuals ending support in that housing type.

- Not stated/other includes those clients whose housing situation at either the beginning or end of support was unknown.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection. Supplementary table MH.4.

Housing outcomes for homeless versus at risk clients

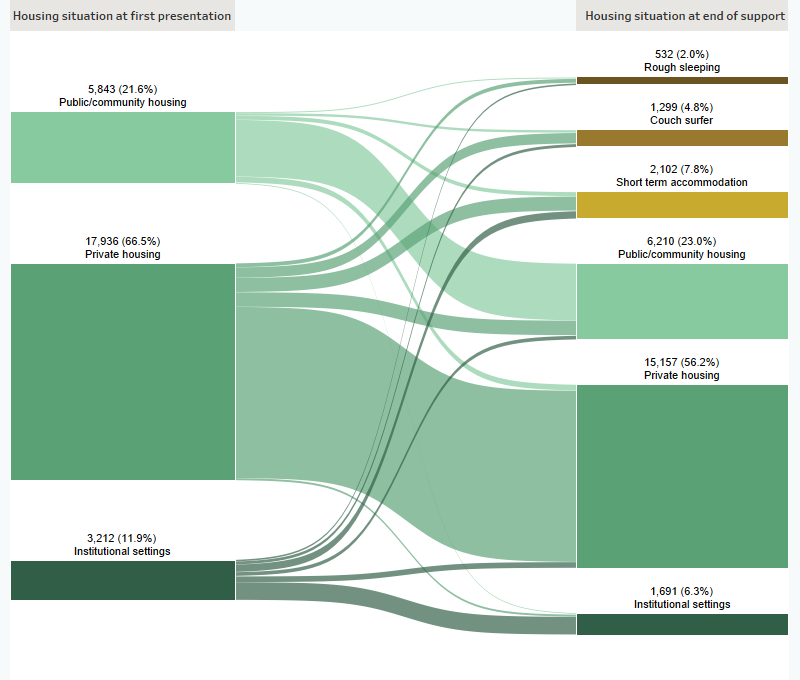

In 2019–20, 51,800 clients had a known housing status at both the start and end of support. Of these clients, almost 27,000 were at risk of homelessness at the start of support, by the end of support (Figure MH.2):

- Most (15,200 clients or 56%) were in private housing

- Around 6,200 clients (23%) were in public or community housing.

A smaller number were experiencing homelessness at the end of support (around 3,900 clients or 15% of those who started support at risk).

Figure MH.2: Housing situation for clients with closed support who began support at risk of homelessness, 2019–20

Notes:

- Excludes clients with unknown housing situation.

- Includes only those clients who ceased support during the financial year (meaning that their support period(s) had closed and they were not in ongoing support at the end of the year).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, 2019–20.

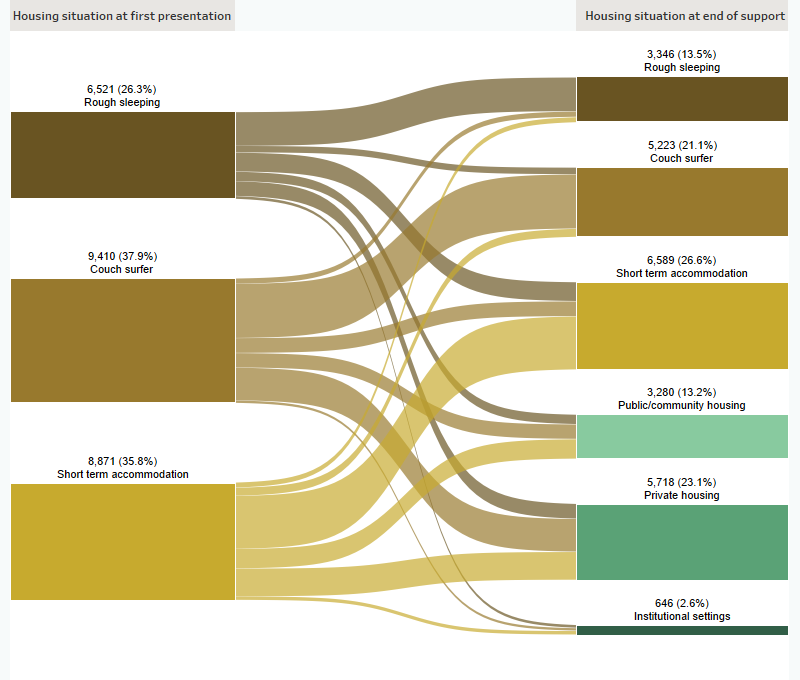

In 2019–20, there were 24,800 SHS clients with a mental health issue who were known to be homeless at the start of support. By the end of support (Figure MH.3):

- 6,600 clients (27%) were in short term accommodation

- 5,700 (23%) were in private housing.

A further 5,200 clients (21%) were couch surfing at the end of support.

Figure MH.3: Housing situation for clients with closed support who were experiencing homelessness at the start of support, 2019–20

Notes:

- Excludes clients with unknown housing situation.

- Includes only those clients who ceased support during the financial year (meaning that their support period(s) had closed and they were not in ongoing support at the end of the year).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, 2019–20.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2008. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007. ABS cat. no. 4326.0 Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2014. Mental Health and Experiences of Homelessness, Australia, 2014. ABS cat. no. 4329.0.00.005. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2018. National Health Survey: First Results 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS

Biddle N, Edwards B, Gray M & Sollis K 2020. Hardship, distress, and resilience: The initial impacts of COVID-19 in Australia, COVID-19 Briefing Paper. ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University, Canberra.

Brackertz N, Wilkinson A & Davison J 2018. Housing, homelessness and mental health: towards systems change. AHURI Research Paper, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Black Dog Institute 2020. Mental Health Ramifications of COVID-19: The Australian context. Viewed 3/08/2020.

CHP (Council to Homeless Persons) 2018. Housing Security, Disability and Mental Health.

Duff C, Jacobs K, Loo S & Murray S 2013. The role of informal community resources in supporting stable housing for young people recovering from mental illness: key issues for housing policy-makers and practitioners. AHURI Final Report No. 199. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Flatau P, Conroy E, Thielking M, Clear A, Hall S, Bauskis A, Farrugia M & Burns L 2013. How integrated are homelessness, mental health and drug and alcohol services in Australia?. AHURI Final Report No.206. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Johnson G & Chamberlain C 2011. Are the Homeless Mentally Ill? Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 46, no. 1: 29–48.

Kaleveld L, Seivwright A, Box E, Callis Z & Flatau P 2018. Homelessness in Western Australia: A review of the research and statistical evidence. Perth: Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities.

MHCA (Mental Health Council of Australia) 2009. Home Truths: Mental Health, Housing and Homelessness in Australia.

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) 2020. National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan. Sydney: NMHC. Viewed 3/08/2020.

Robinson C 2003. Understanding interactive homelessness: the case of people with mental disorders. AHURI report. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Wood L, Flatau P, Zaretzky K, Foster S, Vallesi S & Miscenko, D 2016. What are the health, social and economic benefits of providing public housing and support to formerly homeless people? AHURI Final Report No. 265. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.