Clients leaving care

On this page

People leaving care arrangements, including people transitioning from health care settings (hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, rehabilitation and aged care facilities) and young people transitioning from out-of-home care (foster care and residential care facilities), can find themselves particularly vulnerable to homelessness. This can be due to inadequate transition planning, undertaking discharge assessments in time- or resource-pressured environments and limited options for exit into suitable and secure housing (Brackertz et al. 2018).

People exiting institutions and care into homelessness are a national priority homelessness cohort identified in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement which came into effect on 1 July 2018 (CRRF 2018) (See Policy section for more information).

In 2018–19, around 3,400 young people aged 15–17 were discharged from out-of-home care in Australia (AIHW 2020), corresponding with the end of formal support in the child protection system. One in 3 young people leaving out-of-home care experience homelessness within 12 months of leaving (McDowall 2009). Young people transitioning from out-of-home care face barriers to accessing the same opportunities as their non-care peers who increasingly rely on parental resources in young adulthood (Wilkins et al. 2019). During this accelerated transition to independence, young people leaving care need adequate support to access safe and stable housing, education, employment, financial security, supportive relationships and networks, and life skills (FaHCSIA 2011).

People transitioning from health care settings are also at risk of being discharged into homelessness. In a study of people who have experienced homelessness, 17% had been admitted to hospital for a mental health diagnosis in the previous 2 years (Wood et al. 2016). Discharge from psychiatric hospital in particular has been identified as a key pathway into homelessness among people with mental health issues (Nielssen et al. 2018).

Reporting clients leaving care in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

In the SHSC, a client is identified as transitioning from care arrangements if, in their first support period during the reporting period, either in the week before or at presentation:

- their dwelling type was hospital (excluding psychiatric), psychiatric hospital or unit, disability support, rehabilitation or aged care facility, or

- they identified transition from foster care/child safety residential placements or transition from other care arrangements as a reason for seeking assistance.

Note that these dwelling types are part of the broad housing situation ‘Institutional settings’, which also includes categories relating to custodial arrangements. See the associated section for information specifically relating to Clients exiting custodial arrangements.

For more information see Technical information.

Key findings

- In 2019–20, around 6,700 SHS clients leaving care received assistance from a specialist homelessness services (SHS) agency.

- Over 1 in 4 (28%) stated their dwelling type at the beginning of support was independent housing (house/townhouse/flat). A further 1 in 5 (19%) were staying in a psychiatric hospital/unit and 18% were staying in rehabilitation at the beginning of support.

- Almost 2 in 3 (64%) clients leaving care had received assistance from a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12.

- More than half (55%) of clients leaving care were male.

- The largest age groups were clients aged 35–44 (20%), 25–34 (19%) and 18–24 (19%). A further 1 in 5 clients leaving care were under 18 (19%).

- There was an increase in the proportion of clients who were homeless at the end of support from 26% to 36%.

Client characteristics

In 2019–20 (Table LCARE.1):

- SHS agencies assisted over 6,700 clients leaving care, equating to 2% of all SHS clients in 2019–20.

- There were around 100 fewer SHS clients leaving care compared with 2018–19. The number of SHS clients leaving care has steadily decreased since reaching a peak of 7,100 clients in 2016–17.

- The rate of SHS clients leaving care was 2.7 per 10,000 population, decreasing from 2.9 in 2015–16.

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of clients | 6,869 | 7,104 | 6,917 | 6,834 | 6,728 |

Proportion of all clients | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Rate (per 10,000 population) | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

Notes

- Rates are crude rates based on the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June of the reference year. Minor adjustments in rates may occur between publications reflecting revision of the estimated resident population by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Data for 2015–16 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2015–16 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

- In 2017–18, age and age-related variables were derived using a more robust calculation method. Data for previous years have been updated with the improved calculation method for age. As such, data prior to 2017–18 contained in the SHS Annual Report may not match that contained in the SHS Annual Report Historical Tables.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Age and sex

In 2019–20 (Supplementary table LCARE.1):

- More than half of the clients leaving care were male (55% or around 3,700 clients).

- Almost 3 in 5 (58% or almost 3,900) clients leaving care were aged between 18 and 44; 20% (over 1,300 clients) were aged 35–44, 19% (around 1,300 clients) were aged 25–34 and a further 19% (more than 1,200 clients) were aged 18–24.

- 1 in 5 (19% or almost 1,300) clients leaving care were under 18 and 1 in 10 (9% or almost 590) were under 15.

- A higher proportion of female clients were under 18 (23%, compared with 16% males) while a greater proportion of male clients were over 55 (11%, compared with 8% females).

Indigenous status

In 2019–20, of the clients leaving care whose Indigenous status was known (Supplementary table LCARE.8):

- 1 in 4 (25% or around 1,600 clients) identified as Indigenous

- Female clients who were leaving care were more likely than male clients to identify as Indigenous (29%, compared with 22% of males).

State and territory

In 2019–20 (Supplementary table LCARE.2):

- The largest number of clients leaving care accessed services in Victoria (36% or almost 2,400 clients), followed by New South Wales (27% or around 1,800 clients).

- Despite having some of the lowest numbers of clients leaving care, the Northern Territory had the highest rate of clients leaving care (11.0 clients per 10,000 population), followed by Tasmania (5.8 per 10,000).

Dwelling type at beginning of support

In 2019–20, of the 6,500 clients who were leaving care and stated their dwelling type at the beginning of support (Supplementary table LCARE.12):

- More than 1 in 4 (28% or over 1,800 clients) were living in independent housing (house/townhouse/flat)

- 1 in 5 (19% or around 1,200 clients) were staying in a psychiatric hospital or unit

- 18% (almost 1,200 clients) were staying in rehabilitation

- 14% (around 940 clients) were staying in a hospital (excluding psychiatric).

New or returning clients

In 2019–20 (Supplementary table LCARE.7):

- Of the 6,700 clients leaving care, 36% (around 2,400 clients) were new to the SHSC in 2019–20 and 64% (around 4,300 clients) were returning clients, having previously been assisted by an SHS agency at some point since the SHSC began in 2011–12.

- Half (51% or almost 660 clients) of the clients leaving care who were under 18 were returning clients while 70% (over 860 clients) of clients leaving care who were aged 18–24 were returning clients. These age groups include young people who may have left foster care or other out-of-home care arrangements.

- The proportion of clients leaving care who had previously been assisted by SHS agencies was similar in males and females (63% males, compared with 65% females).

Selected vulnerabilities

Clients may face challenges that make them more vulnerable to experiencing homelessness. The vulnerabilities presented here include family and domestic violence, a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

In 2019–20, of the more than 6,300 clients leaving care who were aged 10 and over, over 4 in 5 (84%) reported experiencing one or more of these vulnerabilities (Table LCARE.2):

- 7 in 10 (70% or almost 4,400 clients) reported a current mental health issue, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

- over 2 in 5 (44% or over 2,800 clients) reported problematic drug and/or alcohol use, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

- 1 in 4 (25% or almost 1,600 clients) reported both a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

- 1 in 6 clients (16% or more than 1,000 clients) reported experiencing none of these vulnerabilities.

Family and domestic violence | Mental health issue | Problematic drug and | Clients | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Yes | Yes | Yes | 608 | 9.6 |

Yes | Yes | No | 574 | 9.1 |

Yes | No | Yes | 94 | 1.5 |

No | Yes | Yes | 1,552 | 24.5 |

Yes | No | No | 262 | 4.1 |

No | Yes | No | 1,664 | 26.3 |

No | No | Yes | 549 | 8.7 |

No | No | No | 1,034 | 16.3 |

|

|

| 6,337 | 100.0 |

Notes

- Clients are assigned to one category only based on their vulnerability profile.

- Clients are aged 10 and over.

- Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2019–20.

Housing situation on first presentation

At the beginning of their first support period in 2019–20, more than 1 in 4 (27%) clients leaving care were experiencing homelessness when they first presented to a SHS agency while 73% were at risk of homelessness (Supplementary table CLIENTS.12).

Service use patterns

In 2019–20, clients leaving care received (Table LCARE.3):

- a median of 66 days of support, an increase from 60 days in 2015–16

- an average of 2.0 support periods per client

- a median of 49 nights of accommodation, with almost half (45%) of the clients receiving accommodation.

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Length of support (median number of days) | 60 | 62 | 63 | 67 | 66 |

Average number of support periods per client | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

Proportion receiving accommodation | 48 | 46 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

Median number of nights accommodated | 42 | 49 | 48 | 48 | 49 |

Notes

- The denominator for the proportion receiving accommodation is all SHS clients who have left care. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

- Data for 2015–16 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2015–16 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

- In 2017–18, age and age-related variables were derived using a more robust calculation method. Data for previous years have been updated with the improved calculation method for age. As such, data prior to 2017–18 contained in the SHS Annual Report may not match that contained in the SHS Annual Report Historical Tables.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2019–20, the main reasons for seeking assistance among clients leaving care were (Supplementary table LCARE.5):

- housing crisis (16% or almost 1,100 clients)

- transition from other care arrangements (12% or over 810 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (10% or over 660 clients).

Clients leaving care who were at risk of homelessness at first presentation were more likely to identify mental health issues (9% of those at risk, compared with 6% experiencing homelessness) and problematic drug or substance use (7%, compared with less than 4% experiencing homelessness) as their main reason for seeking assistance (Supplementary table LCARE.6).

Clients leaving care who were experiencing homelessness at first presentation were more likely to report transition from other care arrangements (18%, compared with 10% at risk) or transition from foster care and child safety residential placements (10%, compared with 5% at risk) as their main reason for seeking assistance.

Services needed and provided

Similar to the overall SHS population, clients leaving care needed general services which were provided by SHS agencies including advice/information, advocacy/liaison on behalf of client and other basic assistance.

Apart from general services, the most common services needed by clients leaving care were (Supplementary table LCARE.3):

- short-term or emergency accommodation (53% or almost 3,600 clients), with 61% receiving this service and a further 10% referred for this service

- long-term housing (51% or around 3,400 clients), with 5% receiving this service and a further 28% referred

- medium-term/transitional housing (47% or over 3,100 clients), with 31% receiving this service and a further 18% referred.

Clients leaving care were more likely than all SHS clients to need services including:

- living skills/personal development (35%, compared with 19%), with 92% receiving this service

- transport (32%, compared with 18%), with 92% receiving this service

- assistance with challenging social/behavioural problems (25%, compared with 12%), with 89% receiving this service

- health/medical services (19%, compared with 9%), with 60% receiving this service and a further 23% referred

- mental health services (21%, compared with 9%), with 52% receiving this service and a further 19% referred.

Outcomes at the end of support

Outcomes presented here describe the change in clients’ housing situation between the start and end of support. Data is limited to clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year—meaning that their support periods had closed and they did not have ongoing support at the end of the year.

Many clients had long periods of support or even multiple support periods during 2019–20. They may have had a number of changes in their housing situation over the course of their support. These changes within the year are not reflected in the data presented here, rather the client situation at the start of their first support period in 2019–20 is compared with the end of their last support period in 2019–20. A proportion of these clients may have sought assistance prior to 2019–20, and may again in the future.

In 2019–20 (Table LCARE.4):

- The most common housing situation for clients leaving care at both the beginning and end of SHS support was institutional settings; over 2,700 clients (61%) at the beginning and around 1,000 clients (25%) at the end of support. Institutional settings include dwelling types such as hospitals, psychiatric hospital/units, rehabilitation and aged care facilities, and clients in this housing situation are considered to be at risk of homelessness rather than experiencing homelessness.

- Over 1 in 3 (36%) clients leaving care were known to be homeless at the end of support, an increase from 26% at the beginning of support.

- 2 in 3 (64%) clients leaving care were known to be housed at the end of support, a decrease from 74% at the beginning of support.

- Although more clients were known to be homeless at the end of support with clients leaving institutional settings, the proportion living in public or community housing increased from 4% to 16% at the end of support and the proportion of clients living in private or other housing increased from 9% to 23%.

- Clients who were known to be homeless were most likely to be staying in short-term temporary accommodation. The proportion of clients in short-term temporary accommodation increased from 13% to 21% at the end of support.

These trends demonstrate that known housing outcomes at the end of support can be challenging for clients transitioning from institutional settings. While some clients progressed towards more positive housing solutions, many remained in/returned to institutional settings or were in temporary accommodation at the end of support. Some clients might only require short-term accommodation immediately after leaving care, others might need more support to access or maintain housing in the long-term.

Housing situation | Beginning of support | End of | Beginning of support | End of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

No shelter or improvised/inadequate dwelling | 232 | 195 | 5.2 | 4.8 |

Short term temporary accommodation | 565 | 854 | 12.7 | 21.1 |

House, townhouse or flat - couch surfer or with no tenure | 353 | 397 | 7.9 | 9.8 |

Total homeless | 1,150 | 1,446 | 25.9 | 35.8 |

Public or community housing - renter or rent free | 179 | 629 | 4.0 | 15.6 |

Private or other housing - renter, rent free or owner | 391 | 947 | 8.8 | 23.4 |

Institutional settings | 2,726 | 1,022 | 61.3 | 25.3 |

Total at risk | 3,296 | 2,598 | 74.1 | 64.2 |

Total clients with known housing situation | 4,446 | 4,044 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Not stated/other | 242 | 644 |

|

|

Total clients | 4,688 | 4,688 |

|

|

Notes

- Percentages have been calculated using total number of clients as the denominator (less not stated/other).

- It is important to note that individual clients beginning support in one housing type need not necessarily be the same individuals ending support in that housing type.

- Not stated/other includes those clients whose housing situation at either the beginning or end of support was unknown.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection. Supplementary table LCARE.4.

Housing outcomes for homeless versus at risk clients

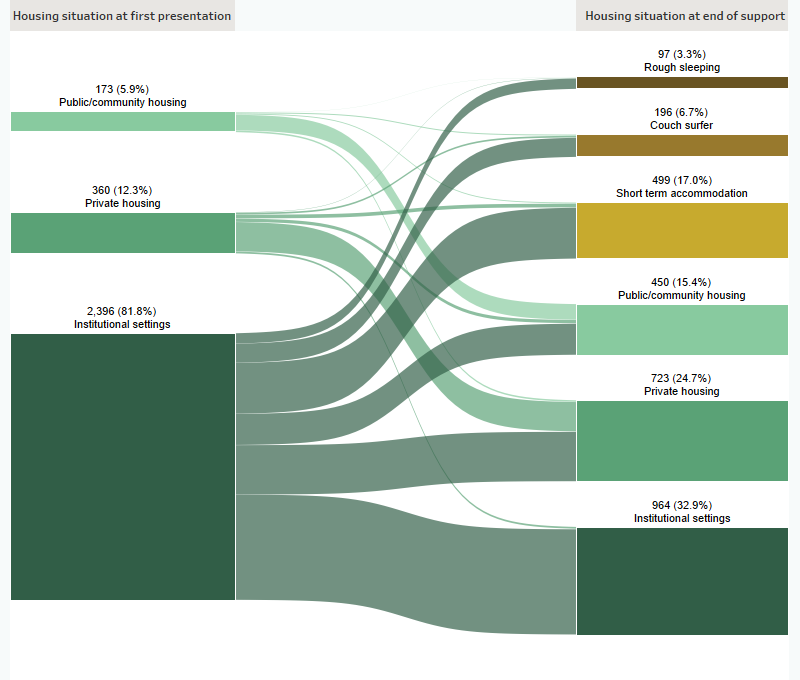

For clients who were at risk of homelessness at the beginning of support and with known housing status at the end of support (around 2,900 clients), by the end of support (Figure LCARE.1):

- One-third (33% or around 960 clients) remained in institutional settings

- 1 in 4 (25% or over 720 clients) were in private housing

- 450 clients (15%) were in public or community housing.

- A further 1 in 4 were experiencing homelessness at the end of support (27% or around 790 clients), many of whom were in institutional settings at the beginning of support (over 720 clients).

Figure LCARE.1: Housing situation for clients leaving care with closed support who began support at risk of homelessness, 2019–20

Notes

- Excludes clients with unknown housing situations.

- Includes only those clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year (meaning that their support period(s) had closed and they were not in ongoing support at the end of the year).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, 2019–20

For clients who were known to be homeless at the beginning of support and with known housing status at the end of support (around 1,000 clients), by the end of support, SHS agencies assisted (Interactive Tableau visualisation):

- One-third (33% or almost 340 clients) into short-term accommodation

- 1 in 5 (20% or around 200 clients) into private housing

- 160 clients (16%) into public or community housing.

50 clients (5%) who were known to be homeless at the beginning of support were staying in institutional settings at the end of support.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2020. Child protection Australia 2018–19. Cat. no. CWS 74. Canberra: AIHW.

Brackertz N, Wilkinson A & Davison J 2018. Housing, homelessness and mental health: towards systems change. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

CFFR (Council on Federal Financial Relations) 2018. National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Viewed 7 August 2020, .

FaHCSIA (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs) 2011. An outline of National Standards for out-of-home care: a priority project under the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020. Canberra: FaHCSIA.

McDowall JJ 2009. CREATE report card 2009 – Transitioning from care: tracking progress. Sydney: CREATE Foundation.

Nielssen OB, Stone W, Jones NM, Challis S, Nielssen A, Elliott G, Burns N, Rogoz A, Cooper LE & Large MM 2018. Characteristics of people attending psychiatric clinics in inner Sydney homeless hostels, The Medical Journal of Australia 208(4): 169-173.

Wilkins R, Laß I, Butterworth P & Vera-Toscano E 2019. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: selected findings from waves 1 to 17. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute.

Wood L, Flatau P, Zaretzky K, Foster S, Vallesi S & Miscenko, D 2016. What are the health, social and economic benefits of providing public housing and support to formerly homeless people? AHURI Final Report No. 265. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.