Illicit drug use

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Illicit drug use, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 October 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Illicit drug use. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/illicit-drug-use

MLA

Illicit drug use. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 10 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/illicit-drug-use

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Illicit drug use [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 Oct. 22]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/illicit-drug-use

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2024, Illicit drug use, viewed 22 October 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/illicit-drug-use

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Illicit drug use affects individuals, families and the broader Australian community. These harms are numerous and include:

- health impacts such as burden of disease, injury, overdose and death

- social impacts such as violence, crime and trauma

- economic impacts such as the cost of health care and law enforcement.

Some population groups are at greater risk of experiencing disproportionate harms associated with illicit drug use, including young people, people with mental health conditions and people who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or intersex (Department of Health 2017).

Definition of illicit drug use

Illicit use of drugs covers the use of a broad range of substances, including:

- illegal drugs – drugs prohibited from manufacture, sale or possession in Australia, including cocaine, heroin and amphetamine-type stimulants

- pharmaceuticals – drugs available from a pharmacy, over-the-counter or by prescription, which may be subject to non-medical use (when used for purposes, or in quantities, other than for the medical purposes for which they were prescribed). Examples include opioid-based pain relief medications, opioid substitution therapies, benzodiazepines, steroids, and over-the-counter codeine (not available since 1 February 2018)

- other psychoactive substances – legal or illegal, used in a potentially harmful way – for example, synthetic cannabis and other synthetic drugs; inhalants such as petrol, paint or glue (Department of Health 2021).

Each data collection cited on this page uses a slightly different definition of illicit drug use; see the relevant report for information.

How common is illicit drug use?

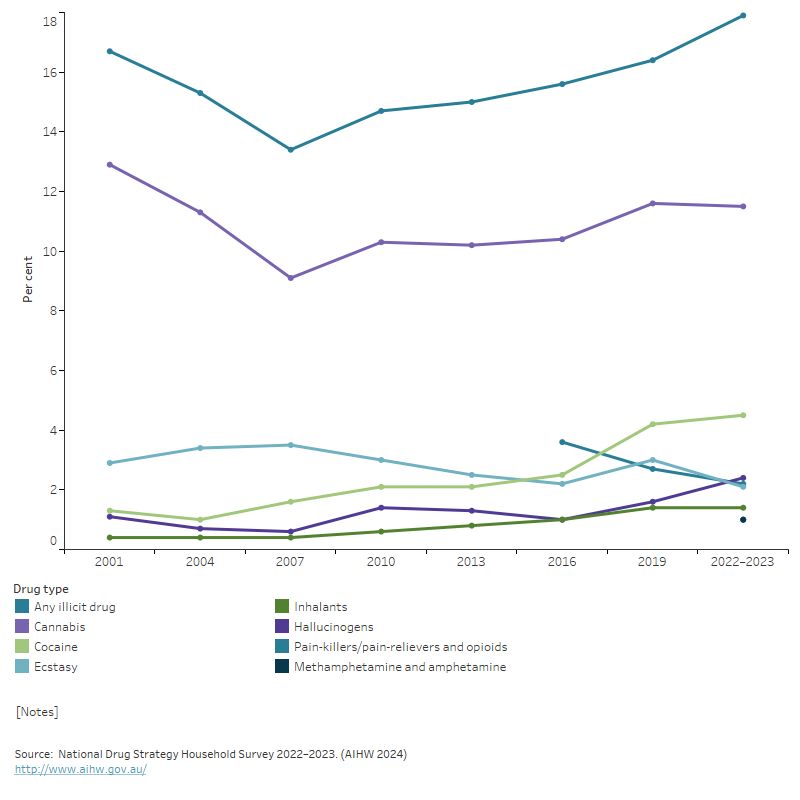

According to the 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS), an estimated 10.2 million (47%) people aged 14 and over in Australia had illicitly used a drug at some point in their lifetime (including the non-medical use of pharmaceuticals), and an estimated 3.9 million (18%) had used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months. This was similar to proportions in 2019 (43% and 16%, respectively) but has increased since 2007 (38% and 13%, respectively) (Figure 1).

In 2022–2023, among people aged 14 and over, the most common illicit drug used recently (in the previous 12 months) continues to be cannabis, 11.5%, similar to use in 2019 (11.6%), followed by cocaine (4.5%) and hallucinogens (2.4%) (Figure 1). A number of changes were reported in the recent use of illicit drugs between 2019 and 2022–2023:

- cocaine (from 4.2% in 2019 to 4.5% in 2022–2023)

- ecstasy (from 3.0% to 2.1%)

- hallucinogens (from 1.6% to 2.4%)

- ketamine (from 0.9% to 1.4%) (Figure 1) (AIHW 2024c).

In 2022–2023, an estimated 1.1 million people (5.3%) aged 14 and over used a pharmaceutical drug for non-medical purposes in the previous 12 months. Between 2019 and 2022–2023, the proportion of people using ‘pain-killers/pain-relievers and opioids' for non-medical purposes declined from 2.7% to 2.2%. This decline is most likely due to a reclassification of medications containing codeine that was implemented in 2018. Under the change, drugs with codeine (including some painkillers) can no longer be bought from a pharmacy without a prescription. The proportion of people using codeine for non-medical purposes has more than halved since 2016, from 3.0% to 1.2% in 2022–2023.

In 2022–2023, pain-killers/pain-relievers and opioids used for non-medical purposes were the fourth most commonly used illicit drug in the previous 12 months after cannabis, cocaine and hallucinogens (AIHW 2024c).

The use of hallucinogens and ketamine have both risen. In 2022–2023, 2.4% of people aged 14 and over had used hallucinogens and 1.4% had used ketamine in their lifetime (AIHW 2024c). Use of hallucinogens and ketamine in the last 12 months was most common among people aged 20–29 (6.8% and 4.2% respectively).

Recent use of methamphetamine and amphetamine was low (1.0%) while lifetime use was high (7.5%) in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024c). The 2022–2023 NDSHS asked about recent use of ‘methamphetamine and amphetamine’, whereas prior NDSHS surveys asked about the use of ‘Methamphetamine or amphetamine’. This change represents a break in the time series; for more information, see Methamphetamine and amphetamine in the NDSHS.

Frequency of illicit drug use

To better understand illicit drug use in Australia, it is important to consider the frequency of drug use and not just the proportion of people who have used a drug in the previous 12 months. Some drugs are used more often than others, and the health risks of illicit drug use increase with the frequency, type, and quantity of drugs used (Degenhardt et al. 2013).

While cocaine and ecstasy were used by more people in the previous 12 months, most people used these drugs infrequently with 58% of people who used cocaine and 59% of people who used ecstasy reporting they only used the drug once or twice a year in the 2022–2023 NDSHS (AIHW 2024c). Conversely, monthly or more frequent drug use was more commonly reported among people who had used cannabis (51%) or methamphetamine and amphetamine (37%).

Figure 1: Proportion of people aged 14 and over who recently used selected illicit drugs, 2001 to 2022–2023

The line graph shows that recent use of any illicit drug decreased between 2001 and 2007, then increased to 2022–2023. Cannabis was the main driver of this effect.

Health impact

Deaths

Drug-induced deaths are defined as those that can be directly attributable to drug use and includes both those due to acute toxicity (for example, drug overdose) and those due to chronic use (for example, drug-induced cardiac conditions) as determined by toxicology and pathology reports (see glossary).

The data on causes of death in this release are sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (ABS 2023a), with additional analysis by the AIHW and National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC).

The ABS preliminary data on causes of death show that of the 1,693 drug-induced deaths in 2022:

- The age-standardised rate of 6.5 deaths per 100,000 population continued the decline of drug-induced deaths since 2017, noting that estimates for 2021 and 2022 are expected to rise following standard revision processes.

- 64% were males (1,082 deaths) and 36% were females (611 deaths).

- The median age at death was higher for females than males (50.0 and 45.4 years, respectively).

- Over two-thirds (69%) of drug-induced deaths in 2022 were considered accidental (1,175 deaths) and 24% (402 deaths) were considered intentional (ABS 2023a, Tables 13.2–13.3).

Preliminary analysis of the AIHW National Mortality Database showed that the vast majority of drug-induced deaths in 2022 (97% or 1,640) were due to the acute effects of drugs, while a further 3.1% (53 deaths) were due to the chronic effects of drugs (including drug-induced cardiac conditions). In addition (Figure 2), in 2022:

- Opioids continued to be the most common drug class present in drug-induced deaths over the past decade (4.0 per 100,000 population in 2022). Opioids include the use of a number of drug types, including heroin, opiate-based analgesics (such as codeine and oxycodone) and synthetic opioid prescriptions (such as tramadol and fentanyl).

- Benzodiazepines were the most common single drug type present in drug-induced deaths (2.7 per 100,000 population) (benzodiazepines are included in the drug class ‘depressants’).

- Over the past decade there has been a substantial rise in deaths involving psychostimulants (such as amphetamines, including methamphetamine). The rate increased from 0.8 per 100,000 population (170 deaths) in 2013 to 1.8 per 100,000 (459 deaths) in 2022.

Figure 2: Drug-induced deaths, by selected drug type and drug class, number and rate, 1997 to 2022

The line graph shows the rate of drug-induced deaths declined between 1999 and 2002, then rose between 2006 and 2017. The rate of deaths then fell across most drug types to 2022.

Analysis by NDARC of preliminary revised data for 2022 indicated that people living in the most disadvantaged areas accounted for the highest percentage of drug-induced deaths (32% or 575 deaths among residents in quintile 1 of the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas). This has remained relatively stable since 2018 (Chrzanowska et al. 2024). Over 3 in 4 overdose deaths (78% or 1,374 deaths) in 2022 occurred at home, consistent with previous years (Chrzanowska et al. 2024).

Burden of disease

According to the Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018, illicit drug use contributed to 3% of the total burden of disease and injury in 2018 (AIHW 2022). This included the impact of opioids, amphetamines, cocaine, cannabis and other illicit drug use, as well as unsafe injecting practices. The rate of total burden of disease and injury attributable to illicit drug use increased by 35% between 2003 and 2018 (AIHW 2022).

Opioid use accounted for the largest proportion (31%) of the illicit drug use burden, followed by amphetamine use (24%), unsafe injecting practices (18%), cocaine use (11%) and cannabis use (10%). Illicit drug use was responsible for almost all burden due to drug use and disorders (excluding alcohol) (AIHW 2022). For more information, see Burden of disease.

Hospitalisations

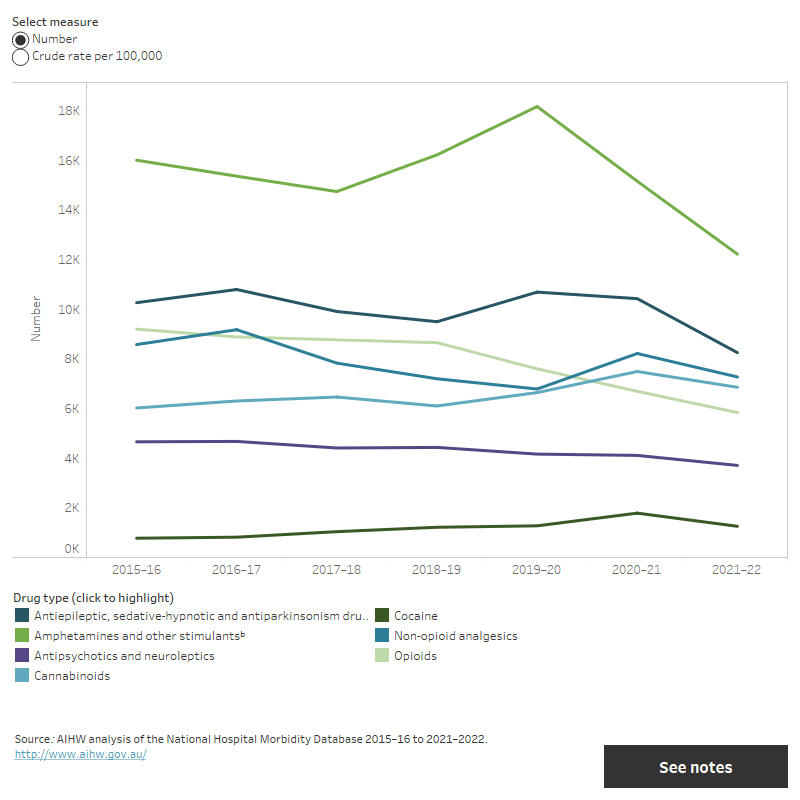

In 2021–22, hospitalisations with a drug-related principal diagnosis accounted for 1.3% of all hospitalisations (135,000). Amphetamines and other stimulants accounted for 9.0% (12,200) of drug-related hospitalisations and most of these related to methamphetamines (82% or 10,100).

In 2021–22, drug-related hospitalisations for:

- Amphetamines and other stimulants decreased to 47 hospitalisations per 100,000 people from 59 hospitalisations per 100,000 people in 2020–21.

- Opioids decreased to 23 hospitalisations per 100,000 people from 26 hospitalisations per 100,000 people in 2020–21 (Figure 3).

- Non-opioid analgesics saw a decrease from 32 hospitalisations per 100,000 people in 2020–21 to 28 hospitalisations per 100,000 people in 2021–22.

For information on drug-related hospitalisations where alcohol was the drug, see Alcohol.

Figure 3: Hospitalisations by selected drug-related principal diagnosis, number and crude rate, 2015–16 to 2021–22

The line graph shows the rate of drug-related hospitalisations for amphetamines and other stimulants has fallen since 2015–16, while for other drugs the rate was fairly stable.

Ambulance attendances

Data on alcohol and other drug-related ambulance attendances are sourced from the National Ambulance Surveillance System (NASS). Monthly data are available from 2021 for people aged 15 years and over for New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory.

Across reporting jurisdictions:

- The highest number and rate of ambulance attendances for illicit drugs were for cannabis, amphetamines (any) and heroin.

- 'Any type of pharmaceutical drug’ required a higher rate of transport to hospital than other drugs, ranging from 85% of attendances in the Australian Capital Territory to 92% of attendances in Queensland.

- The highest proportion of ambulance attendances where police co-attended involved Amphetamines (any). This was less likely where a pharmaceutical drug was involved.

- Over half (55%) of any pharmaceutical drug-related attendances involved at least one other drug (excluding alcohol) (AIHW 2024b).

Non-fatal overdose

Data from the 2023 Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) and Ecstasy and related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) include rates of self-reported overdose. In 2023:

- 1 in 10 (11%) IDRS participants reported a non-fatal opioid overdose in the past 12 months (Sutherland et al. 2023b).

- 1 in 7 (15%) EDRS participants reported experiencing a non-fatal stimulant overdose in the past 12 months; this was stable relative to 2020 (18%) (Sutherland et al. 2023a).

Treatment

The Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report shows amphetamines have consistently been the most common illicit principal drug of concern since 2015–16. In 2022–23, amphetamines accounted for 24% of treatment episodes, followed by cannabis at 17% then heroin at 4.5% (AIHW 2024a).

Treatment episodes for amphetamines as the principal drug of concern almost doubled between 2013–14 and 2019–20 (from 29,000 to 61,000), before falling to 52,000 in 2022–23. Between 2013–14 and 2022–23, treatment episodes for heroin declined from 12,000 to 9,700 and fluctuated for cannabis, peaking at 45,000 in 2015–16 (AIHW 2024a).

For more information, see Alcohol and other drug treatment services.

Social impact

The social impacts of illicit drug use are pervasive and include criminal activity, engagement with the criminal justice system and victimisation. For example:

- Just under 2 in 5 participants of the 2023 IDRS (38%) and 2023 EDRS (35%) reported participating in criminal activities. The most common criminal activities were property crime and selling drugs for cash profit (Sutherland et al. 2023a, 2023b).

- In 2022–2023, 1 in 10 (10.1%) people aged 14 and over had been a victim of an illicit drug-related incident (experiencing verbal abuse, physical abuse or being put in fear) in the previous 12 months, remaining stable since 2019 (10.5%) (AIHW 2024c).

- In 2020–21, almost one-quarter of victims (23%) and 9% of offenders had consumed illicit drugs or non-therapeutic levels of pharmaceutical drugs before a homicide incident (Bricknell 2023).

Priority populations

The National Drug Strategy 2017–2026 specifies priority populations who have a high risk of experiencing direct and indirect harm as a result of drug use, including young people, people with mental health conditions and people who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or intersex (Department of Health 2017).

Young people

Young people are susceptible to permanent damage from alcohol and other drug use as their brains are still developing, which makes them a vulnerable population (Department of Health 2017).

As a group, young people aged 14–29 in 2022–2023 were less likely to have used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months than people of the same age in 2001. Drug use and trends in young people however, vary considerably within this age range. For example:

- In 2001, 28% of 14–19 year olds had used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months, but by 2022–2023, this had decreased to 19% (AIHW 2024c).

- In 2022–2023, people aged 20–29 were the most likely to have used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months (33%), a similar proportion to 2019 (31%).

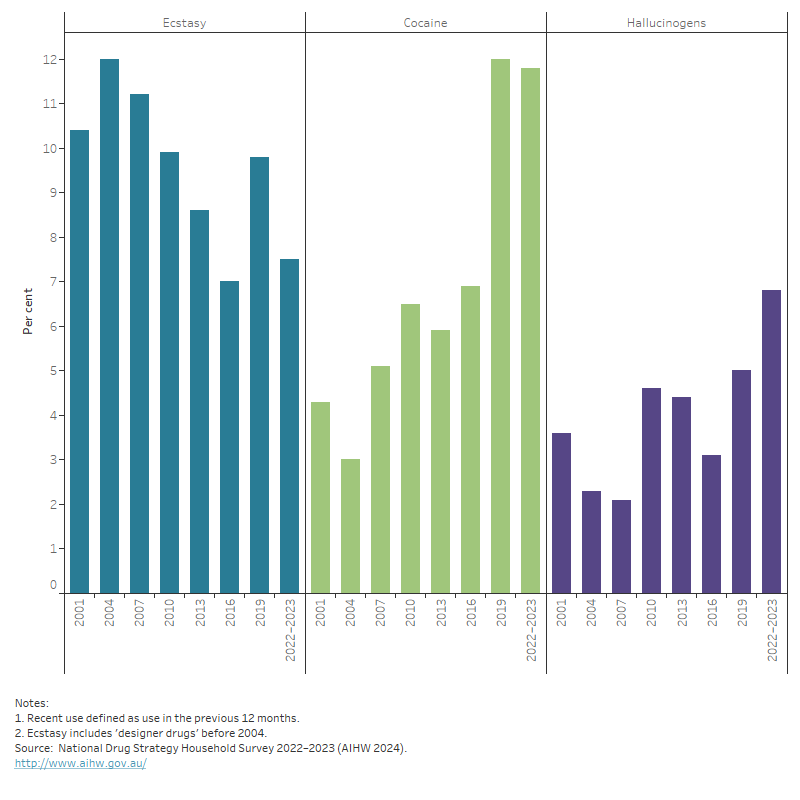

- There have been significant changes in the types of drugs used by people in their 20s (Figure 4):

- Ecstasy use among people in their 20s declined from 9.8% in 2019 to 7.5% in 2022–2023. This was likely driven by a reduction in supply and opportunities to use ecstasy following COVID-19 related public health measures and event restrictions.

- Cocaine use among people in their 20s has increased steadily since 2001. Much of the rise in cocaine use among people in this age group occurred between 2016 and 2019 – from 6.9% in 2016 to 12% in 2019 where it remained stable in 2022–2023.

- Hallucinogen use among people in their 20s has increased steadily since 2001. Between 2016 and 2022–2023, hallucinogen use in this age group more than doubled – from 3.1% in 2016 to 6.8% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024c).

See also Health of young people.

Figure 4: Proportion of people aged 20–29 who recently used ecstasy, cocaine or hallucinogens, 2001 to 2022–2023

The bar graph shows that ecstasy use was higher than cocaine use until around 2019, when cocaine became more common. Use of hallucinogens is lower but has been rising since 2016.

People with mental health conditions

The presence of a mental health condition may lead to a drug use disorder, or vice versa. In some cases where there is a comorbidity, the person who uses drugs can develop a drug use disorder as a consequence of repeated use to relieve or cope with mental health symptoms (Marel et al. 2016).

The ABS National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing reports prevalence estimates of 12-month mental disorders as the number of people who met the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder at some time in their life and had sufficient symptoms of that disorder in the previous 12 months. The 2020–2022 study found:

- 3.3% of Australians (647,900 people) aged 16–85 years had symptoms of a 12-month Substance Use disorder.

- 4.4% of males reported a 12-month Substance Use disorder, compared with 2.1% of females (ABS 2023b).

In 2022–2023, the NDSHS showed that the proportion of people self-reporting a mental health condition was higher among people aged 18 and over who reported the use of illicit drugs in the previous 12 months (29%) than those who had not used an illicit drug over this period (16%) (AIHW 2024c). For example, mental health conditions were reported by:

- 44% of people who recently used methamphetamine and amphetamine (compared with 18% of non-users)

- 27% of people who recently used hallucinogens ( 18% of non-users)

- 30% of people who recently used cannabis (16% of non-users)

- 25% of people who recently used ecstasy (18% of non-users)

- 26% of people who recently used cocaine (18% of non-users) (AIHW 2024c).

Just over half of the participants in the 2023 IDRS (53%) and 2023 EDRS (58%) self-reported mental health conditions in the previous 6 months. The IDRS saw an increase from 2022 (47%) and the EDRS was stable relative to 2022 (62%) (Sutherland et al. 2023a, 2023b). For more information, see Physical health of people with mental illness.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, gender diverse, and queer people

People who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, gender diverse or queer can be at an increased risk of licit and illicit drug use. These risks can be increased by a number of issues such as stigma and discrimination, familial issues, fear of discrimination and fear of identification (Department of Health 2017). The NDSHS provides substance use estimates by sexual orientation for people who are lesbian, gay or bisexual, as well as estimates for people who are transgender or gender diverse (AIHW 2024c).

The NDSHS has consistently shown that the proportion of people reporting illicit drug use has been higher among people who are lesbian, gay or bisexual than among heterosexual people – 47% compared with 16%, had used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months in 2022–2023. After adjusting for differences in age, in comparison to heterosexual people, lesbian, gay or bisexual people were:

- 12.2 times as likely to have used inhalants in the previous 12 months

- 3.8 times as likely to have used hallucinogens in the previous 12 months

- 6.5 times as likely to have used methamphetamine and amphetamine in the previous 12 months

- 5.6 times as likely to have used ecstasy in the previous 12 months (AIHW 2024c).

The types of illicit drugs people had used in the last 12 months varied quite considerably by a person’s sexual orientation and it is important to note that there are differences in substance use between people who are gay or lesbian and people who are bisexual (AIHW 2024c).

The Writing Themselves In National Report describes findings from the national survey of health and wellbeing among lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, asexual (LBGTQA+) young people in Australia. The survey was conducted from September to October 2019 and participants needed to be aged between 14 and 21 years. The survey shows that in the previous 6 months:

- 27% of participants aged 14 to 17 years and 43% of participants aged 18 to 21 years reported using any drug for non-medical purposes

- 28% of participants reported using cannabis

- 7.0% of participants reported using ecstasy/MDMA (Hill et al. 2022a).

The Private Lives survey is Australia’s largest national survey of the health and wellbeing of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) people, with the age of participants ranging from 18 to 88 years. The survey showed that 44% of participants reported using one or more drugs for non-medical purposes in the previous 6 months. Of this, cannabis was the highest at 30%, followed by ecstasy/MDMA at 13.9%.

Within the past 6 months, 14.0% of participants reported experiencing a time when they had struggled to manage their drug use or where it negatively impacted their everyday life (Hill et al. 2022b).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on illicit drug use, see:

- Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia

- National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023

- Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report

- Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: interactive data on risk factor burden

- National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre

For more on this topic, see Illicit use of drugs.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023a) Causes of Death, Australia, 2022, ABS cat. no. 3303.0, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 31 October 2023.

ABS (2023b) National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2020–22, ABS cat no. 4326.0, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 28 November 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 28 September 2021.

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 June 2024.

AIHW (2024b) Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 April 2024.

AIHW (2024c) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 February 2024.

Bricknell S (2023) Homicide in Australia 2020–21 Statistical Report no. 42. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 31 March 2023.

Chrzanowska A, Man N, Sutherland R, Degenhardt L and Peacock A (2024) Trends in overdose and other drug-induced deaths in Australia, 2003–2023, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, accessed 28 May 2024.

Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Baxter AJ, Charlson FJ et al. (2013) Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, The Lancet 382(9904):1564–74, accessed 5 April 2022.

Department of Health (2017) National Drug Strategy 2017–2026, Department of Health and Aged Care website, accessed 24 January 2024.

Department of Health (2021) Types of drugs, Department of Health and Aged Care website, accessed 24 January 2024.

Hill AO, Lyons A, Jones J, McGowan I, Carman M, Parsons M, Power J and Bourne A (2022a) Writing Themselves In 4: The health and wellbeing of LGBTQA+ young people in Australia, National report, monograph series number 124. Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, accessed 22 March 2022.

Hill AO, Bourne A, McNair R, Carman M and Lyons A (2022b) Private Lives 3: The health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ people in Australia, ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 122. Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, accessed 22 March 2022.

Marel C, Mills KL, Kingston R, Gournay K, Deady M, Kay-Lambkin F, Baker A and Teesson M (2016) Guidelines on the management of co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings (2nd edition), Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health and Substance Use, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, accessed 5 April 2022.

Sutherland R, Karlsson A, King C, Uporova J, Chandrasena U, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Grigg J, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, and Peacock A (2023a) Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, accessed 25 October 2023.

Sutherland R, Uporova J, King C, Chandrasena U, Karlsson A, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Agramunt S, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M and Peacock A (2023b) Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) Interviews, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, accessed 25 October 2023.