Tobacco and e-cigarettes

Key findings

View the Tobacco and e-cigarettes in Australia fact sheet >

Tobacco is made from the dried leaves of the tobacco plant and nicotine is the active ingredient responsible for its addictive properties. Tobacco is usually smoked in a cigarette, cigar or pipe, but it might also be snorted or chewed. Nicotine can now also be inhaled as a vapour through electronic nicotine delivery systems (see electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes)).

Tobacco use in Australia is legal, however, its supply and consumption are subject to strict regulations. The advertising of tobacco is prohibited in Australia. In recent years, the restrictions have expanded to ban advertising at the point of sale and include the introduction of plain packaging.

Smoking is also banned inside restaurants, bars and clubs, in cars with children and around many public places such as near children’s play equipment, swimming pools, public transport, and around public buildings.

Availability

Retailing laws in each jurisdiction regulate the advertising, promotion and display of tobacco products, e-cigarettes and accessories, non-tobacco smoking products and age requirements for purchase.

Latest available industry sales data from Tobacco in Australia indicate that the value of retail sales of tobacco products including cigarettes, cigars and smoking tobacco has increased from 2016 to 2017, despite the quantity of cigarette sticks sold declining (Scollo & Bayly, Table 10.6.1). In 2017, supermarkets contributed to the largest volume of cigarette sales at 7,734 million, followed by tobacconists/tobacco specialists at 2,489 million. Overall, total cigarette sales decreased by 6.7% from 2016 to 2017 (Scollo & Bayly, Table 10.6.2).

Data on the availability of illicit tobacco in Australia are limited. However, the level of illicit trade of tobacco in Australia is considered to be low (Scollo & Bayly 2019). The Australian Tax Office (ATO) estimated that the amount of lost excise revenue from illicit tobacco in 2017–18 ($647 million) was 5% of the amount of collectable tobacco excise (ATO 2019).

Consumption

For related content on tobacco consumption by region, see also:

There has been a long-term downward trend in tobacco smoking in Australia. The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) found:

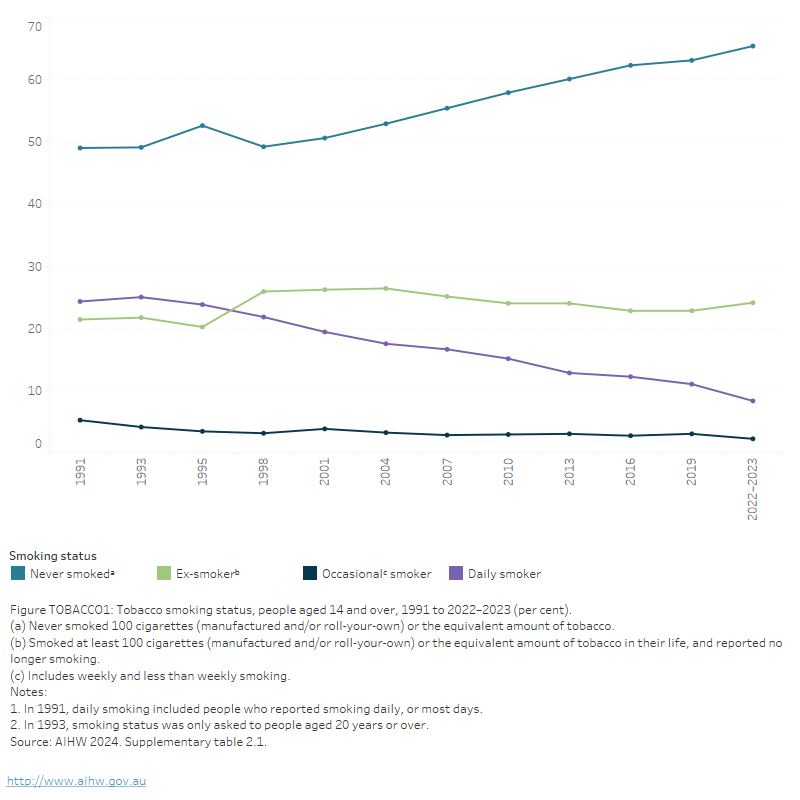

- The proportion of people aged 14 and over smoking daily more than halved from 24% in 1991 to 8.3% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.1).

- The proportion of people aged 14 and over who have never smoked has increased to the highest levels since the survey began (from 49% in 1991 to 65% in 2022–2023) (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.1; Figure TOBACCO 1).

- The long-term decline in daily smoking has largely been driven by people never taking up smoking rather than people quitting smoking (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.1, Figure TOBACCO 1).

When interpreting these findings, it is useful to consider the proportion of people who had ever smoked but no longer smoked (the ‘quit proportion’). This proportion increased from 42% in 1991 to 62% in 2019 (Greenhalgh et al. 2020).

Figure TOBACCO 1: Tobacco smoking status, people aged 14 and over, 1991 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

This line graph shows that the proportion of people aged 14 and over who have never smoked consistently increased between 1998 and 2022–2023, while the proportion of daily smokers decreased consistently between 1993 and 2022–2023. The proportion of ex-smokers has remained stable since 1998 and the proportion of occasional smokers remained stable between 1995 and 2022–2023. The never smoked group has consistently has consistently had the highest proportion while the occasional smoking group has consistently had the lowest.

Data from the National Health Survey (NHS) show a similar pattern to the NDSHS data over time. The proportion of adults who smoke daily (aged 18 or older) declined steadily over the 2 decades to 2022, and after adjusting for age, has halved from 22.3% in 2001 to 10.7% in 2022. Over recent years the proportion of adults who smoke daily declined slightly from 14.7% in 2014–15 (ABS 2023, Table S1.3; age standardised).

Estimates using self-reported NHS data show that in 2022:

- 1 in 10 people (10.6%) aged 18 years and over currently smoked daily.

- Men were more likely to smoke daily than women (12.6% compared with 8.7%) (ABS 2023, Table 14.3).

For more information about the differences between the NDSHS and the NHS, refer to Box TOBACCO 1.

The National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (NWDMP) measures the presence of substances in sewerage treatment plants across Australia. Nicotine (including cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and nicotine replacement products such as gums and patches) is typically among the most commonly consumed substances monitored by the program (ACIC 2024).

The most recent data from the NWDMP show that the estimated population-weighted average consumption of nicotine (including tobacco products, e-cigarettes and nicotine replacement products, such as gums and patches) has remained relatively stable since the start of the program in 2016. The most recent reporting period (April and August 2023) showed that the average consumption was higher in regional areas compared with capital cities (ACIC 2024).

For state and territory data, see the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program reports

Box TOBACCO 1: National data sources on smoking and alcohol consumption

A number of nationally representative data sources are available to analyse recent trends in tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. The AIHW National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) and the ABS National Health Survey (NHS) have large sample sizes and collect self-reported data on tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption.

Data from the NDSHS and NHS show variations in estimates, yet comparison of trends over time are consistent between the 2 surveys. Differences in scope, collection methodology and design may account for this variation and comparisons between collections should be made with caution. For example:

Data are collected for people aged 14 years and over for the NDSHS and people aged 18 years and over for the NHS. Estimates are provided for people aged 18 years and over for both surveys.

NDSHS respondents could choose to complete the survey via a self-complete drop and collect questionnaire, online survey or computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI).

The questions asked in the surveys also differ and therefore results from the surveys are not directly comparable (ABS 2023; AIHW 2024c).

For more information on the technical details of these surveys, please see the technical notes and data quality sections for the NDSHS and NHS.

For information about data sources examining tobacco, alcohol and other drug use by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people, see also: Box INDIGENOUS 2.

Types of tobacco products consumed

Trends in the type of tobacco product consumed by people who smoke has changed over the past decades. Data from the 2022–2023 NDSHS found that, of people who currently smoke:

- The proportion of people who smoked manufactured cigarettes exclusively declined from a peak of 74% in 2004 to 56% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024c, Table 2.24).

- The proportion who smoked roll-your-own cigarettes exclusively increased from 5.7% in 2001 to 16% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024c, Table 2.24).

- Over 1 in 5 (22%) people aged 18–24 smoked roll-your-own cigarettes exclusively, the highest of any age group (AIHW 2024c, Table 2.25).

Menthol cigarettes are flavoured tobacco products that contain menthol additive in the cigarette filter or filler. Menthol cigarettes, while smoked less frequently than non-menthol cigarettes, may be more difficult to quit as menthol modifies the effects of nicotine on the brain (Winnall et al. 2023).

According to the 2022–2023 NDSHS almost one quarter of people who smoke daily (23%) reported smoking menthol cigarettes on a daily basis (AIHW 2024c, Table 2.26).

Expenditure on tobacco products

Adjusting for increasing prices of tobacco products (so that all prices are expressed in current-day terms), expenditure estimates for tobacco have declined from $44 billion in 1990 to $32 billion in 2000 and $17.2 billion in 2018 (Bayly & Scollo 2019). ABS National Accounts data have found that estimates of expenditure on tobacco also suggest continuing declines in consumption (ABS 2018).

Tobacco smoking by age and gender

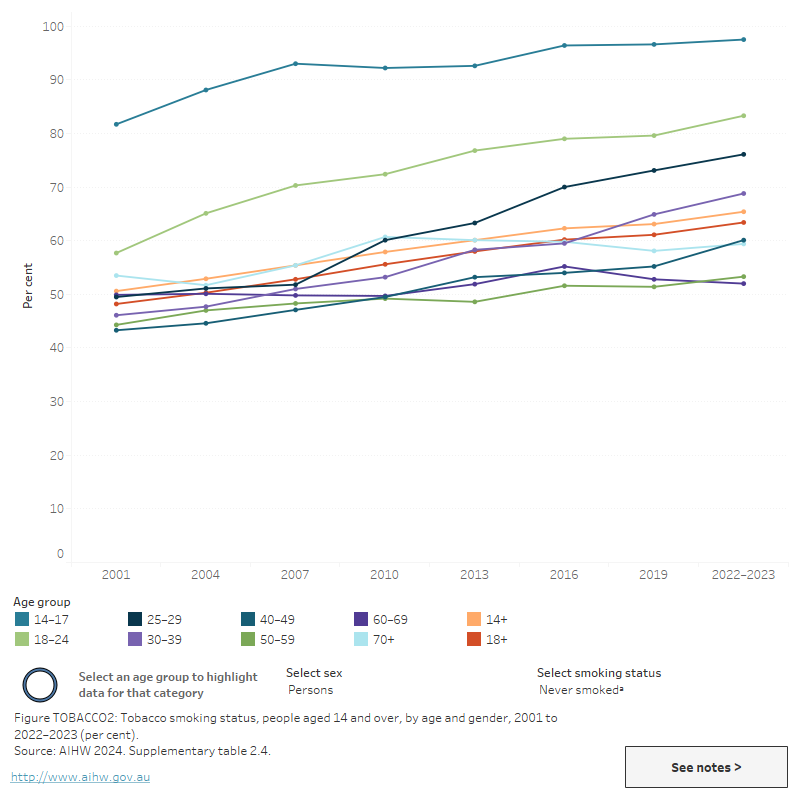

Findings from the 2022–2023 NDSHS (Figure TOBACCO2; AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4) showed that:

- People aged 50–59 (12.1%) were the most likely age group to smoke daily (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4).

- In people aged 14 and over, males (9.0%) were more likely to smoke daily than females (7.7%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4).

- Young adults aged 18–24 years were more likely to have never smoked than any other adult age group (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4).

- The average age at which younger people (aged 14–24 years) had their first full cigarette decreased from 16.6 years in 2019 to 16.3 years in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.18).

For more information from the NDSHS on smoking rates and trends over time, see Tobacco and e-cigarettes/vapes.

Data from the 2022 NHS showed that:

- People aged 55–64 years (14.9%) had the highest proportion for daily smoking (ABS 2023, Table 14.3)

- Of people aged 18 and over, a higher proportion of men (12.6%) than women (8.7%) currently smoked daily (ABS 2023, Table 14.3)

- 79% of 18–24-year-olds reported never smoking in 2022, up from 75% in 2017–18 (ABS 2023, ABS 2019)

- The number of cigarettes smoked per day increased with age – 8.2% of people who smoked aged 18–24 years smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day, compared with 26.5% of those aged 65 years and over (ABS 2023, Table 14.3).

Recent estimates from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey show declines in daily smoking for both males (from 21.4% to 12.4%) and females (from 15.8% to 9.5%) between 2003 and 2021 (Wilkins et al. 2024). Declines in daily smoking were noted across most age groups, with greater declines for those in younger age groups.

Figure TOBACCO 2: Tobacco smoking status, people aged 14 and over, by age and gender, 2001 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

This line graph shows the proportion of people aged 14 and over who smoked daily, occasionally, in the past or never, by age group, from 2001 to 2022–2023. Daily smoking declined for all age groups between 2001 and 2022–2023, the largest declines were for the following age groups, 14–17, 18–24, 25–29 and 30–39. In 2007, the age group with the highest proportion of people who smoke daily was 20–29 years, while 14–17 years was the group with the lowest. However in 2022–2023, the age group of 50–59 had the highest proportion of people who smoke daily while the 14–17 year age group had the lowest. People under 24 have consistently had the highest proportion of people who never smoke. The figure includes a filter to view data by gender.

Geographic trends

Since 2001, the proportion of people aged 14 and over who smoked daily has declined across all jurisdictions and socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2024b).

For more information on State and Territory tobacco trends see Data by region – Tobacco.

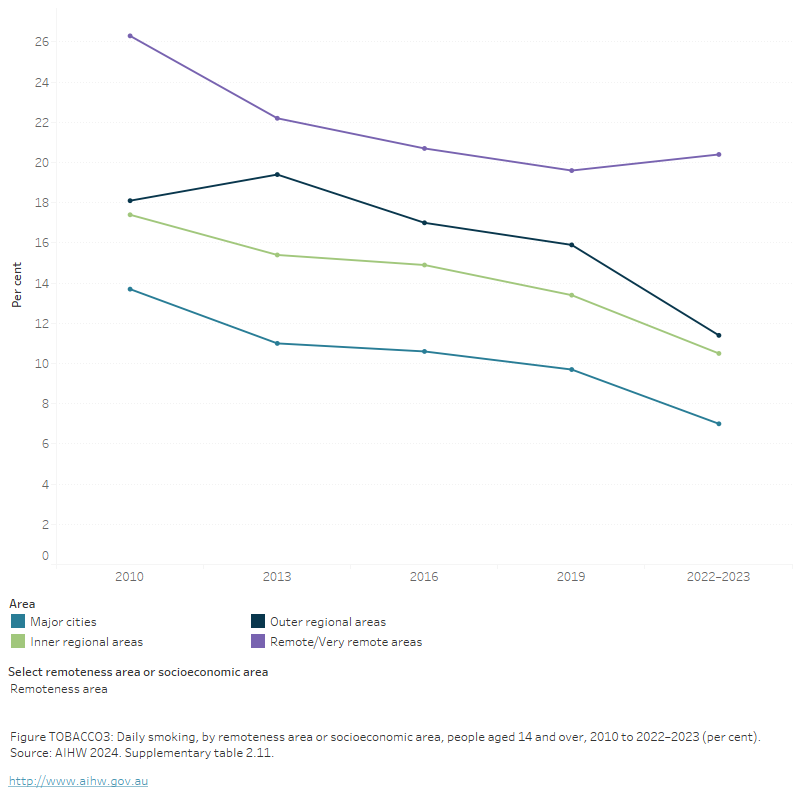

The 2022–2023 NDSHS found a decrease in the proportion of people (aged 14 and over) who smoked daily in most areas, with the exception of Remote and very remote areas, where daily smoking rates remained stable. Specifically, the proportion of people who smoked daily and resided in:

- Major cities decreased (from 9.7% in 2019 to 7.0% in 2022–2023)

- Inner regional areas decreased (13.4% to 10.5% in 2022–2023)

- Remote and very remote areas (20%) were more likely to smoke daily than those in Major cities (7%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 9a.12; Figure TOBACCO 3).

Similarly, results from the 2022 NHS found adults (aged 18 or older):

- living in Outer regional and Remote areas were around 1.5 times as likely to smoke daily as those in Major cities (16.7% compared with 9.4%) (ABS 2023, Table 6.3).

In general, people who live in disadvantaged areas of Australia were around 3 times as likely to smoke daily than those living in the most advantaged areas. Specifically:

- The 2022–2023 NDSHS found 13.4% of people aged 14 and over living in the most disadvantaged areas smoked daily, compared with 4.1% of people living in the most advantaged areas (AIHW 2024b, Table 9a.14).

- Similar results were reported in the 2022 NHS, where 18.1% of adults aged 18 and over living in the most disadvantaged area smoked daily, compared with 5.4% of those living in the least disadvantaged group (ABS 2023, Table 6.3).

Figure TOBACCO 3: Daily smoking, by remoteness area or socioeconomic area, people aged 14 and over, 2010 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows the proportion of daily smoking status for people aged 14 and over by socioeconomic area for 2010, 2013, 2016 and 2019, for the National Drug Strategy Household Survey. Daily smoking has declined across all 5 socioeconomic areas between 2010 and 2019. In 2019, people living in the most disadvantaged areas of Australia were more likely to smoke daily than those who live in the most advantaged areas (18.1% compared with 5.0%).

The most recent data from the NWDMP show that the estimated population-weighted average consumption of nicotine (including tobacco products, e-cigarettes, and nicotine replacement products, such as patches and gum) is typically higher in regional areas than capital cities (ACIC 2024).

Smoking cessation

The addictive nature of nicotine means that successful cessation may take many attempts over several years. Data from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that:

- 62% of people who currently smoked had future intentions to quit (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.39).

Of those who had changed their smoking behaviour:

- 53% did so because it was costing too much

- 45% did so because it was affecting their health or fitness (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.35)

For more data from the NDSHS on smoking cessation, see Did people who smoke try to quit or reduce their smoking?.

Data from the HILDA Survey indicate that between 2.1% and 3.5% of people quit smoking in any given year between 2003 and 2021. However, 3 in 5 (61.5%) people who quit smoking between 2003 and 2018 started smoking again within 3 years (Wilkins et al. 2024). Males were more likely than females to start smoking again after quitting (63.6% and 59%, respectively). These data are likely an underestimate as people who quit and start smoking again between annual survey waves will not be counted in these estimates (Wilkins et al. 2024).

Illicit tobacco

Illicit tobacco includes both unbranded tobacco and branded tobacco products on which no excise, customs duty or Goods and Services Tax (GST) was paid.

Unbranded illicit tobacco includes finely cut, unprocessed loose tobacco that has been grown, distributed, and sold without government intervention or taxation (AIHW 2024c). According to the NDSHS, in 2022–2023:

- Over 2 in 5 (43%) people who smoke were aware of unbranded tobacco – an increase from 34% in 2019.

- Almost one quarter (23%) of all people who smoke had smoked unbranded tobacco in their lifetime (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.30).

Illicit branded tobacco includes tobacco products that are sold in Australia without the plain packaging/graphic health warnings that are required by law. The 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that:

- More people who currently smoke had seen tobacco products without plain packaging/graphic health warnings in the previous 3 months (20% compared with 15.2% in 2019).

- Of the 10% of people who currently smoke who purchased these products, 40% said they purchased them from a tobacconist and 26% said they bought them from a supermarket, convenience or grocery store (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.31).

Data on the availability of illicit tobacco in Australia are limited. However, the level of illicit trade of tobacco in Australia is considered to be low (Scollo & Bayly 2019). The Australian Tax Office (ATO) estimated that the amount of lost excise revenue from illicit tobacco in 2021–22 ($2.3 billion) was 13% of the amount of collectable tobacco excise (ATO 2023).

Harms

Burden of disease and injury

Tobacco is the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in Australia. The Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018, found that tobacco smoking was responsible for 8.6% of the total burden of disease and injury. Estimates of the burden of disease attributable to tobacco use showed that cancers accounted for 44% of this burden (AIHW 2021).

Tobacco use contributed to the burden for 8 disease groups including 39% of respiratory diseases, 22% of cancers, 11% of cardiovascular diseases, 6.2% of infections and 3.2% of endocrine disorders (AIHW 2021, Table 6.3).

The total burden attributable to tobacco use has been declining since 2003. There was a 32% decline in the age-standardised rate (from 2003 to 2018), and the proportion of total burden due to tobacco use fell from 10.4% in 2003, to 9.0% in 2015, to 8.6% in 2018 (AIHW 2021).

Tobacco smoking in pregnancy

Tobacco smoking during pregnancy is a preventable risk factor for pregnancy complications, and support to stop smoking is widely available through antenatal clinics. Smoking is associated with poorer perinatal outcomes, including low birth weight, being small for gestational age, pre-term birth and perinatal death (AIHW 2023b).

The AIHW’s National Perinatal Data Collection indicates that the proportion of mothers who smoke during pregnancy has fallen over time in Australia. In 2021, 8.7% (or 26,433) of all mothers who gave birth smoked at some time during their pregnancy, down from 13.2% in 2011. The proportion of mothers who smoked during pregnancy declined for both First Nations mothers and non-Indigenous mothers (AIHW 2023b).

Exposure to second-hand smoke

The inhalation of other people’s tobacco smoke can be harmful to health. Second-hand smoke causes coronary heart disease and lung cancer in non-smoking adults, and induces and exacerbates a range of mild to severe respiratory effects in infants, children and adults. Second-hand smoke is a cause of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and a range of other serious health outcomes in young children. There is increasing evidence that second-hand smoke exposure is associated with psychological distress (Campbell, Ford & Winstanley 2017).

Results from the 2022–2023 NDSHS show that parents and guardians are choosing to reduce their children’s exposure to tobacco smoke at home. The proportion of households with children aged under 14 where someone smoked inside the home on a daily basis has fallen from 31% in 1995 to 2.1% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.14).

In 2022–2023, 2.6% of adults who did not smoke were exposed to tobacco inside the home on a daily basis (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.16).

For more data from the NDSHS about household exposure see “How many people were exposed to tobacco smoke at home?”

Results from the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) found over half (63% or 85,768) of young Indigenous people aged 15–24 reported someone in their household smoked daily (AIHW 2018). Less than one-fifth (15% or 21,155) of young Indigenous people resided in a household where someone smoked indoors (AIHW 2018).

Treatment

The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set (AODTS NMDS) provides information on treatment provided to clients by publicly funded AOD treatment services, including government and non-government organisations. Data collected for the AODTS NMDS are released twice each year, via an early insights report in April and a detailed annual report mid-year.

The latest Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report shows that nicotine accounts for only a small proportion of treatment episodes provided to clients each year. In 2022–23, nicotine was the principal drug of concern in 1.1% of treatment episodes for clients’ own drug use (AIHW 2024a, Table Drg.5; Figure TOBACCO 4).

In 2022–23, where nicotine was the principal drug of concern:

- over half of clients (53%) were male and around 1 in 6 (18%) were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people (AIHW 2024a, tables SC.9 and SC.11)

- almost 2 in 3 clients were aged 10–19 (30%), 20–29 (16%), or 30–39 (18%) (AIHW 2024a, Table SC.10)

- the most common source of referral into treatment was health services (32% of episodes), followed by self or family (21%) (AIHW 2024a, Table Drg.13)

- the most common treatment types were counselling (34% of episodes) and assessment only (29%) (AIHW 2024a, Table Drg.45; Figure TOBACCO 4).

The low proportion of treatment episodes for nicotine likely relates to the widespread availability of support and treatment for nicotine use in the community. This includes general practitioners, pharmacies, helplines, and web services (AIHW 2024a).

Figure TOBACCO 4: Treatment provided for client's own nicotine use, 2022–23

Nicotine was the principal drug of concern in 1.1% of treatment episodes

Around 1 in 6 clients were First Nations people

Counselling was the most common main treatment type (almost 1 in 3 episodes)

Source: AIHW 2024, tables Drg.1, SC.11 and Drg.45.

Smoking cessation medicines

Data from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) provide information on the number of prescriptions dispensed and the number of patients supplied at least one script under the PBS within a given financial year. The PBS database includes information about medicines that are used to help people stop their smoking (smoking cessation medicines).

Some smoking cessation medicines, such as Nicotine Replacement Therapies (NRT; for example, nicotine patches and gums), are available over-the-counter (OTC) as well as via a prescription. OTC NRT data are not captured in the PBS data as OTC medicines are not subsidised under the PBS. For more information, refer to the Technical notes and Box PHARMS 2.

Data from the PBS indicate that around 323,600 scripts for prescription smoking cessation medicines were dispensed to 160,000 patients in 2021–22, a rate of 1,300 scripts and 620 patients per 100,000 population (Supplementary data tables PBS61–64). Between 2012–13 and 2021–22, dispensing rates fluctuated but overall fell from 2,200 scripts dispensed and 1,400 patients to 1,300 scripts and 620 patients per 100,000 population (tables PBS62 and PBS64).

In 2021, global distribution of Varenicline (marketed in Australia as Champix), a prescription medicine that assists adults to stop smoking, was paused due to manufacturing issues causing a long-term shortage (TGA 2021). This should be taken into consideration when comparing data with previous years.

In 2021–22:

- Rates of smoking cessation medicine dispensing were higher for males than females.

- Males aged 60–69 had the highest rates of scripts dispensed (around 2,600 scripts per 100,000) and males aged 50–59 had the highest rates of patients who were dispensed smoking cessation of any group (1,300 patients per 100,000 population) (Tables PBS66 and PBS68).

- People aged 40–49, 50–59 and 60–69 had the highest rates of dispensing (Tables PBS66 and PBS68). For more information on PBS dispensing by age group, see Older people: Treatment.

- Rates of dispensing were highest in Outer regional areas and dispensing varied between states and territories (tables PBS69–76). For more information, see Data by region.

At-risk groups

For related content on at-risk groups, see:

Despite large reductions in tobacco smoking over time, there are challenges associated with addressing the inequality of smoking rates between some populations and the broader community.

- The proportion of people who currently smoke is disproportionately high among First Nations people.

- People aged 50–59 were one of the age groups most likely to smoke daily in 2019. The highest proportion of people who smoke who were not planning to quit smoking were aged 70 and over.

- People with mental health conditions or high psychological distress are twice as likely to smoke daily as people without mental health conditions and those with low distress.

Electronic cigarettes (vapes)

Electronic cigarettes (also known as e-cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems, personal vaporisers or vapes) are devices designed to deliver nicotine and/or other chemicals via inhalation of an aerosol vapour (Department of Health and aged Care 2021). Most e-cigarettes contain a battery, a liquid cartridge and a vaporisation system and are used in a manner that simulates smoking (ACT Health 2021). The solution used in e-cigarettes varies. Common e-liquids include propylene glycol, vegetable glycerol, and flavourings, and may contain nicotine in freebase or salt form (Banks et al. 2022).

The 2022–2023 NDSHS showed both lifetime and current use of e-cigarettes increased between 2016 to 2019, and again to 2022–23. Specifically:

- Lifetime use of e-cigarettes increased from 11.3% in 2019 to 19.8% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.1).

- Current use of e-cigarettes increased from 2.5% in 2019 to 7.0% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.3).

For people who currently use e-cigarettes:

- Around 1 in 2 (49%) used them daily, an increase from 2019 (42%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.8).

- Almost 3 in 4 (73%) reported the last one they used contained nicotine (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.16).

Social and economic factors shape people’s behaviours of vaping or smoking. Generally, people living in the lowest socio-economic areas were the most likely to currently smoke but not vape, (13.2% in 2022–2023). By contrast, people living in the highest socio-economic areas were the most likely to vape but not smoke (6.6%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.43).

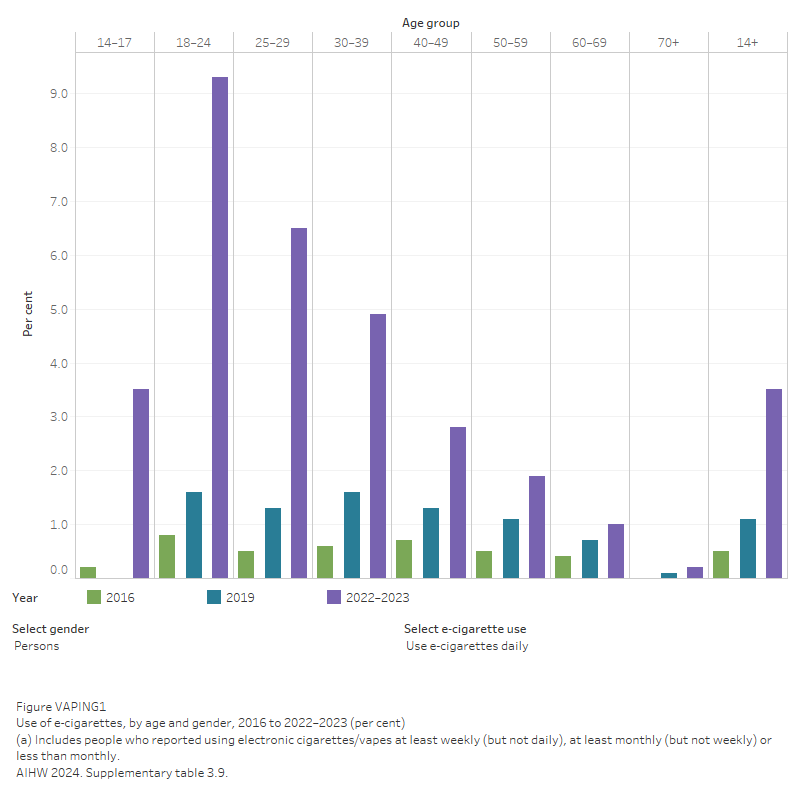

Daily use of e-cigarettes was more common among younger people than people of older age groups (Figure VAPING 1). Data from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that:

- People aged 18–24 had the highest rate of daily vaping (9.3%). Daily vaping was slightly more common among females in this age group (10.3%) than males (8.5%).

- People aged 25–34 were the most likely to report they used to use e-cigarettes but no longer use them (6.0%).

In 2022–2023, the average age of initiation for e-cigarette use was:

- 19.4 years for those who had never smoked a cigarette, a decrease from 20.2 years in 2019

- 25.8 years for people who smoke socially

- 33.0 years for people who smoke regularly, a decrease from 38.1 years in 2019 (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.33).

Figure VAPING 1: Use of e-cigarettes, by age and gender, 2016 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

This bar chart shows that the proportion of people who currently vaped in 2022–2023 was highest in the 18–24-year age group, and decreased among each subsequent age group.

The report Current vaping and current smoking in the Australian population age 14+ years: February 2018 – March 2023 found a marked increase in the 6 monthly population prevalence of current vaping that began in late 2020 and continued to early 2023. In early 2023:

- 18–24 year olds had the highest 6 monthly prevalence of current vaping (19.8%), followed by those aged 25–34 (17.4%) and 14–17 (14.5%).

Annual prevalence estimates of exclusive smoking gradually trended downwards, while the prevalence of exclusive vaping and dual use both trended upwards. In early 2023:

- Exclusive vaping was most common amongst 18–24 years old (12.5%), dual use was most common amongst those aged 14–17 (10.7%), and exclusive smoking was highest amongst those aged 35–49 (11.1%).

- For those aged 14–17, there were more people who currently vape (14.5%) than currently smoke (12.8%), whilst among those aged 35 and older, more people smoke than vape (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b).

The National Health Survey 2022 reported:

- About 1 in 7 (14%) people aged 18 years and over had used an e-cigarette or vaping device at least once. 4.0% reported currently using a device.

- Almost 1 in 5 (18%) young people aged between 15 and 17 had used an e-cigarette or vaping device at least once.

- Men were more likely than women to have used an e-cigarette or vaping device at least once (17% compared to 11%) (ABS 2023).

Questions on vaping were included in the HILDA Survey for the first time in 2021. These data indicate that 14.1% of people aged 15 and over had tried vaping or e-cigarettes in 2021 (Wilkins et al. 2024).

- Around 16% of people who had tried vaping reported using vapes daily.

- People who currently smoke were the most likely to use e-cigarettes at least monthly (13.4% for both males and females), while those who had never smoked were the least likely (1.1% for males and 1.0% for females) (Wilkins et al. 2024).

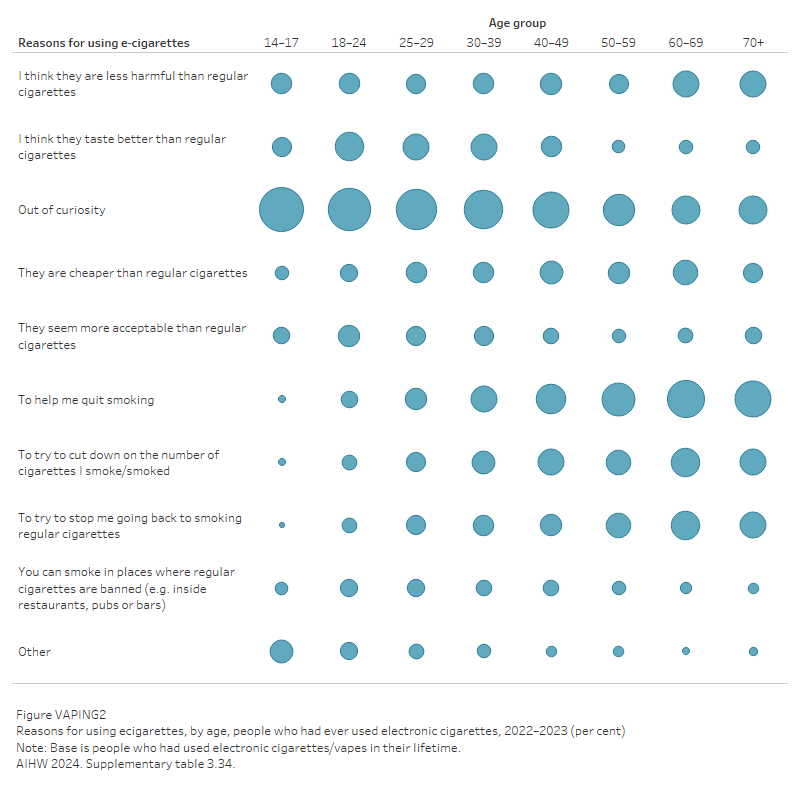

Reasons for using e-cigarettes (Vapes)

While use of e-cigarettes is more common among younger age groups in Australia, their reasons for using e-cigarettes are different to that of older people. According to the 2022–2023 NDSHS, the most common reason for trying e-cigarettes was curiosity (57%), but this varied by age. Specifically:

- Curiosity was the most common reason for vaping among people aged 14–17 (74%) and 18–24 (68%).

- To help them quit smoking was the most common reason for vaping among people aged 60–69 (53%) and 70+ (49%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.34, Figure VAPING 2).

Figure VAPING 2: Reasons for using e-cigarettes, by age, people who had ever used electronic cigarettes, 2022–2023 (per cent)

This circle chart shows that across all age groups, it was uncommon for people to vape because they can vape in places where regular cigarettes are banned.

For more data from the NDSHS on e-cigarette use see Tobacco and e-cigarettes/vapes.

The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 will develop and implement measures to restrict marketing, availability, consumption and the environmental impact of e-cigarettes (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a).

All Australian governments have agreed to the policy and regulatory approach to e-cigarettes in Australia.

Further information about e-cigarettes can be found on the Department of Health and Aged Care’s website and health advice from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Policy-context

There has been a long-term commitment to addressing the harms associated with tobacco smoking in Australia, through a range of measures such as taxation on tobacco products, restrictions on advertising, and the prohibition of smoking in certain locations.

There is a high level of support among the general population in Australia for measures aimed at reducing tobacco-related harm. According to the 2022–2023 NDSHS, of people aged 14 and over:

- 81% supported banning the advertising of tobacco products on social media.

- 78% supported banning additives (flavouring) in cigarettes and other tobacco products to make them less attractive to young people (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.46).

Support for measures to reduce the problems associated with e-cigarettes and vaping was also high, specifically:

- 86% of people supported prohibiting the sale of e-cigarettes/vapes, including those without nicotine, to people under 18 years of age.

- 80% of people supported restricting the use of e-cigarettes in public places (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.44).

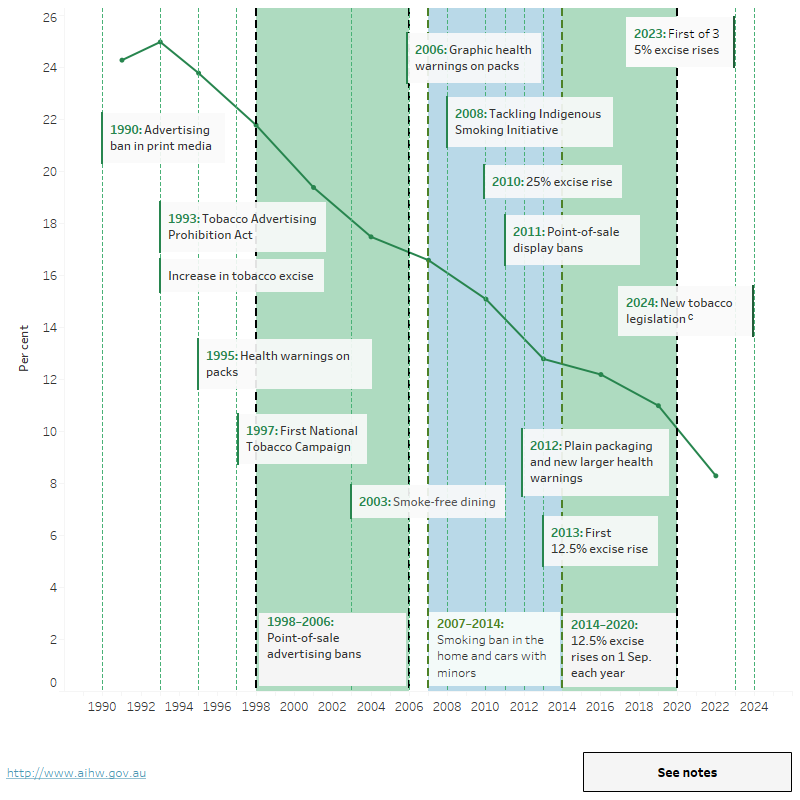

Figure TOBACCO 5 shows the daily smoking rate and key national tobacco policy implementation points over time. In 1991, 24% of the population aged 14 years and over smoked daily, this rate fell to 8.3% in 2022–2023.

Figure TOBACCO 5: People aged 14 and over who smoke dailyab and key tobacco control measures in Australia, 1990 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows the daily smoking proportion for people aged 14 and over and key national tobacco policy implementation points (such as tobacco tax increases and health campaigns) over time. In 1991, 24% of the population aged 14 years and over smoked daily, this rate more than halved to 11% in 2019.

National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030

The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 is a sub-strategy of the National Drug Strategy 2017–2026 and aims to improve the health of all Australians by reducing tobacco use and the associated health, social, environmental and economic costs. Objectives of the strategy include:

- Prevent the uptake of tobacco use.

- Prevent and reduce the use of tobacco among First Nations people.

- Denormalise and limit the marketing and use of e-cigarettes.

- Ensure tobacco control is guided by focused research, monitoring and evaluation.

- Setting targets to:

- Reduce the national daily smoking prevalence to less than 10% by 2025 and less than 5% by 2030.

- Reduce the daily smoking rate among First Nations people to 27% or less by 2030 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a).

National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030

Tobacco control is also a key component of the Australian Government’s 10-year National Preventive Health Strategy and includes a range of policy achievements that aim to reduce tobacco use and nicotine addiction. The 4 overarching aims of the National Preventive Health Strategy are:

- All Australians have the best start in life.

- All Australians live in good health and wellbeing for as long as possible.

- Health equity is achieved for priority populations.

- Investment in prevention is increased (Department of Health 2021).

Prescribing for nicotine vaping products

From 1 October 2021, a prescription is required to import and/or purchase nicotine vaping products (including nicotine e-cigarettes, nicotine pods and liquid nicotine) from Australia or overseas. From 1 January 2024 the importation of all disposable vapes was banned unless the importer holds a licence and permit, and from 1 March 2024 the importation of other vaping goods including devices, accessories and substances will require a licence and permit.

For more information, see the Nicotine vaping products hub.

Resources and further information

- National Preventive Health Strategy 2021 - 2030

- National Tobacco Strategy 2023 – 2030

- Department of Health and Aged Care - Tobacco control

- Comprehensive resource on tobacco smoking in Australia – Cancer Council

- Department of Health - About e-cigarettes

- Department of Health - Illicit tobacco

- Inquiry to illicit tobacco

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2012) Australian Health Survey: First Results, 2011–12. ABS cat. no. 4364.0. Canberra: ABS.

ABS (2017) Household expenditure survey, Australia: summary of results, 2015–16. ABS cat. no. 6530.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 4 January 2018.

ABS (2018) Australian System of National Accounts, 2017-18. ABS cat. no. 5204.0. Canberra: ABS.

ABS (2019a) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017-18, expanded confidentialised unit record file, DataLab. ABS cat no. 4324.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

ABS (2019b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19. ABS cat. no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 8 January 2020.

ABS (2023) National Health Survey, ABS Website, accessed 3 January 2024.

ACIC (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission) (2024) National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program Report 21. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 14 March 2024.

ACT Health (2021) Electronic cigarettes. ACT Health. accessed 3 March 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2018) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth health and wellbeing 2018. Cat. no. IHW 202. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government.

AIHW (2023a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report. Cat. No. HSE 250. Canberra: AIHW. accessed 21 June 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Australia's mothers and babies, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 June 2023.

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report. Cat. No. HSE 250. Canberra: AIHW. Accessed 14 June 2024.

AIHW (2024b) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 04 March 2024.

ATO (Australian Taxation Office) (2019) Illicit tobacco. ATO website. Viewed 18 May 2020.

ATO (2024). Excise duty rates for tobacco. ATO website, accessed 19 April 2024.

Banks E, Yazidjoglou A, Brown S, Nguyen M, Martin M, Beckwith K, Daluwatta A, Campbell S, Joshy G (2022) Electronic cigarettes and health outcomes: systematic review of global evidence. Report for the Australian Department of Health. National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Canberra: April 2022, accessed 3 March 2023.

Campbell MA, Ford C & Winstanley MH (2017) The health effects of secondhand smoke, 4.0 background. In Scollo MM & Winstanley MH (eds). Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. Viewed 19 February 2019.

Department of Health (2017) Tobacco control timeline. Department of Health website, accessed 20 April 2018.

Department of Health (2021) National Preventive Health Strategy 2021-2030. Department of Health website, accessed 4 August 2022.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) About e-cigarettes, Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed 3 March 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023a) National Tobacco Strategy 2023-2030. Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed 3 May 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023b) Current vaping and smoking in the Australian population aged 14 years or older – February 2018 to March 2023. Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed 8 September 2023.

Greenhalgh EM, Jenkins S, Stillman S & Ford C (2020) 7.2 Quitting activity. In Greenhalgh, EM, Scollo, MM and Winstanley, MH [editors]. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. Viewed 3 June 2021.

Scollo M (2019) Dutiable tobacco products as an estimate of tobacco consumption. In Scollo MM and Winstanley MH (eds). Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. Viewed 12 June 2019.

Scollo M & Bayly M (2021) Retail value and volume of the Australian tobacco market. In Scollo MM & Winstanley MH (eds). Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. Accessed 6 July 2022.

TGA (2021) Varenicline | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Therapeutic Goods administration Website. Viewed 1 September 2023.

Wilkins R, Vera-Toscano E and Botha F (2024) The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 21, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, the University of Melbourne. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Winnal, WR, Jenkins S, and Scollo MM (2023) 12.7 Menthol. In Greenhalgh EM, Scollo MM and Winstanley MH [editors]. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2023. Accessed 27 February 2024.