Maternal medical conditions

Maternal medical conditions

On this page:

The burden of disease – including the prevalence of chronic diseases – is higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (AIHW 2020).

Diabetes and hypertension (high blood pressure) are significant sources of maternal illness and death (Marschner et al. 2023). Pregnant women with pre-existing or gestational diabetes or pre-existing or gestational hypertension disorders have increased risk of developing adverse outcomes in pregnancy.

Diabetes

Diabetes affecting pregnancy can be pre-existing (that is, type 1 or type 2) or may arise because of the pregnancy (gestational diabetes).

Box 1: Types of diabetes in pregnancy

- Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease, which destroys the cells in the pancreas. The pancreas produces insulin, and people need insulin replacement to survive. It is usually diagnosed in childhood or early adulthood.

- Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes at the population level. People with Type 2 diabetes produce insulin, but do not produce enough, and/or cannot use it effectively. It involves a genetic component, but is largely preventable, and associated with a later onset. Modifiable risk factors for type 2 diabetes include physical inactivity, poor diet, being overweight or obese, and tobacco smoking.

- Gestational diabetes is characterised by glucose intolerance of varying severity, which develops or is first recognised during pregnancy, mostly in the second or third trimester. It usually disappears after the baby is born but can recur in later pregnancies (AIHW 2023) (for more information see Gestational diabetes).

The type and severity of complications differs according to the type of diabetes experienced in pregnancy and can have both short-term and long-term implications (AIHW 2023).

In the short-term, diabetes in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of caesarean section birth, induced labour, failed induction of labour, pre-existing hypertension, pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth, stillbirth, low and high birthweight, resuscitation, and special care nursery/ neonatal intensive care unit admission (AIHW 2023; AIHW 2019a). Mothers with gestational diabetes –and their babies – experience complications at a lower rate than mothers with pre-existing diabetes (AIHW 2023).

Long term effects of diabetes in pregnancy include increased future risk of other chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, for both mothers with gestational diabetes during pregnancy and their babies (AIHW 2019a).

Management of diabetes in pregnancy depends on the severity of the disease and can include lifestyle programs, which involve changes to diet and exercise, oral glucose-lowering drugs, non-insulin injectable glucose-lowering medications, insulin injections, or a combination of these methods (AIHW 2019b; Wood et al. 2021).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are at increased risk of developing type 2 and recurrence of gestational diabetes and may face structural and practical barriers in preventing and managing diabetes in pregnancy including socioeconomic disadvantage, food insecurity, lack of opportunities and facilities for participating in physical activity and competing priorities such as caring responsibilities (AIHW 2019; Wood et al. 2021).

A recent survey of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with a history of diabetes in pregnancy, and health professionals, found that women and their care givers preferred diabetes management programs that were co-designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, involved connections with community, culture and Country, promoted healthy food options, and acknowledged and advocated for change at the structural level (Wood et al. 2021).

This report shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and had pre-existing diabetes were more likely than those who had no diabetes to give birth to a baby who was pre-term, had either low birthweight or high birthweight or were large for gestational age.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were diagnosed with gestational diabetes during their pregnancy were also more likely to give birth to a baby who was large for gestational age than mothers who did not have diabetes (for more information on the effect of maternal diabetes see Outcomes for babies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers). In 2020, 0.1% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth had type 1 diabetes, 1.9% had type 2 diabetes and 15% had gestational diabetes (compared with 0.3%, 0.4% and 14%, respectively, of non-Indigenous females).

Between 2014 and 2020 the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers with type 2 diabetes ranged from 1.2% to 1.9%. Over the same period the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers with gestational diabetes has increased (from 9.3% in 2014 to 15% in 2020).

The data visualisation below shows the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by diabetes status, from 2014.

Figure 1: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by diabetes status from 2014 to 2020

Line graph for diabetes type by Indigenous status. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers with gestational diabetes increased.

In 2020, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and lived in the most disadvantaged areas were more likely to have pre-existing diabetes (3.1%) and gestational diabetes (16%) compared with those who lived in the least disadvantaged areas (0.9% and 14%, respectively).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who gave birth and lived in Remote and Very remote areas were more likely to have pre-existing diabetes (4.1% and 5.6%, respectively) than those who lived in Major cities (1.5%) and were also more likely to have gestational diabetes (17% for Remote areas, 21% for Very remote areas and 13% for Major cities).

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers with pre-existing diabetes increased with maternal age, from 0.5% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers under 20 years and 1.2% of those aged 20-24 years, to 5.5% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers aged 35-39 years and 10% of those aged 40 years and over.

This pattern was also seen for gestational diabetes, increasing from 8.0% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers under 20 years and 11.1% of those aged 20-24 years, to 24% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers aged 35-39 years and 26% of those aged 40 years and over.

The proportion Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and had gestational diabetes was lower for first-time mothers (13%) than those with a parity of 3 (19%) and 4 or more (18%).

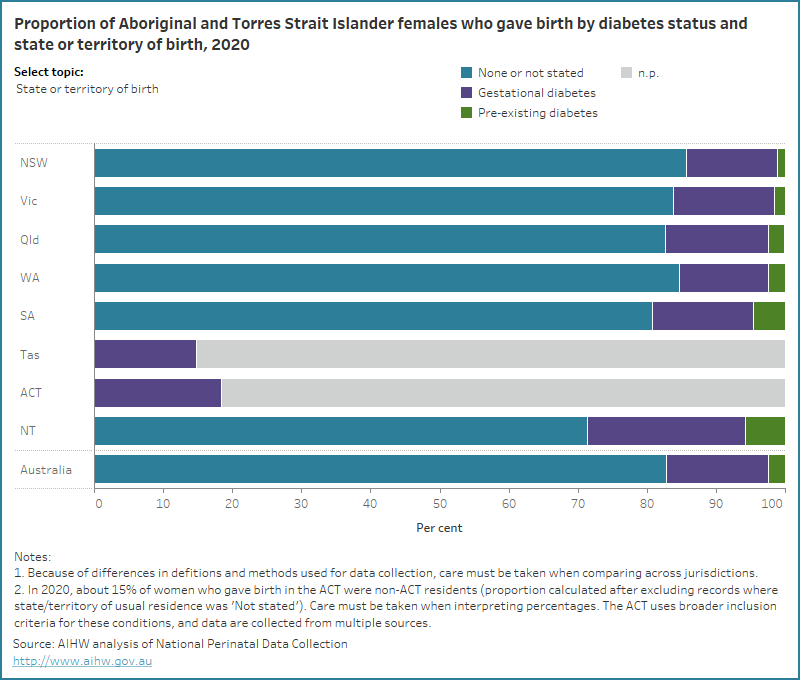

The data visualisation below presents data on the diabetes status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics for 2020.

Figure 2: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth by diabetes status and selected topic for 2020

Bar chart for diabetes status by selected topics. 15% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers had gestational diabetes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who lived in some geographical locations were more likely to have gestational diabetes. Explore the map below to view data on the number and proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who had gestational diabetes, by IREG and PHN for 2020 and SA3 for 2017-2020.

Figure 3: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and had gestational diabetes by various geographies

Map of proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who had gestational diabetes across Australia grouped by various geographies.

Hypertension

Hypertension affecting pregnancy can be pre-existing (that is, chronic) or may arise or worsen because of the pregnancy (gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia).

Box 2: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

- Chronic hypertension: a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more or a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or more (DoHAC 2020). In pregnancy, chronic hypertension is confirmed prior to conception or prior to 20 weeks gestation (Queensland Health, 2021).

- Gestational hypertension: a form of hypertension that is first diagnosed after 20 weeks gestation. Blood pressure returns to normal after the baby is born (DoHAC 2020).

- Pre-eclampsia: a multi-system disorder characterised by hypertension diagnosed after 20 weeks of pregnancy, increased protein in the urine and involvement of one or more other organ systems and/or the fetus (DoHAC 2020).

Complications of hypertension that can affect the mother include cerebral injury, liver and kidney failure, increased risk of maternal mortality and recurrence of gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies (Queensland Health 2021). Complications which can affect the baby include being born pre-term, being small for gestational age, being admitted to the special care nursery and increased risk of stillbirth (Queensland Health 2021).

A study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women found they had higher risk factors associated with hypertension, including pre-pregnancy obesity and features of the metabolic syndrome (waist circumference of 80cm or more, plus two or more of the following: high triglycerides, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and low high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol levels (Campbell et al. 2013).

In 2020, 1.2% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth had chronic hypertension, 3.4% had pre-eclampsia and 3.2% had gestational hypertension (compared with 0.9%, 2.3% and 3.4%, respectively, of non-Indigenous females).

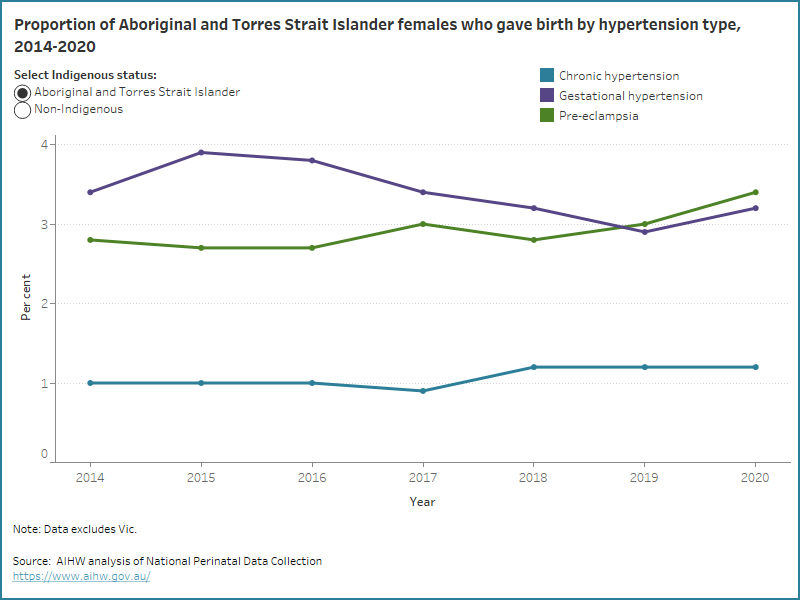

Between 2014 and 2020, the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers with chronic hypertension ranged from 0.9% to 1.2%, with pre-eclampsia ranged from 2.7% to 3.4% and with gestational hypertension ranged from 2.9% to 3.9%.

The data visualisation below shows the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by hypertension type, from 2014.

Figure 4: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by hypertension type from 2014 to 2020

Line graph by hypertension type by Indigenous status. Around 3% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers had pre-eclampsia.

In 2020 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth were more likely to be living with pre-existing hypertension if they lived in the most disadvantaged areas (1.3%), lived in Remote areas (1.9%), were aged 35-39 years (3.6%) and had a parity of 3 or 4 or more (both 1.8%).

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers with gestational hypertension ranged from:

- 2.3% for those who lived the most disadvantaged areas to 3.2% in the second and third areas of disadvantage (3.2% for both quintile 2 and quintile 3)

- 1.8% for those who lived in Very remote areas to 4.0% of those who lived in Inner regional areas

- 2.5% for those aged 20-24 years to 6.0% aged 40 years and over

- 3.9% for first-time mothers to 2.0% for those with a parity of 2.

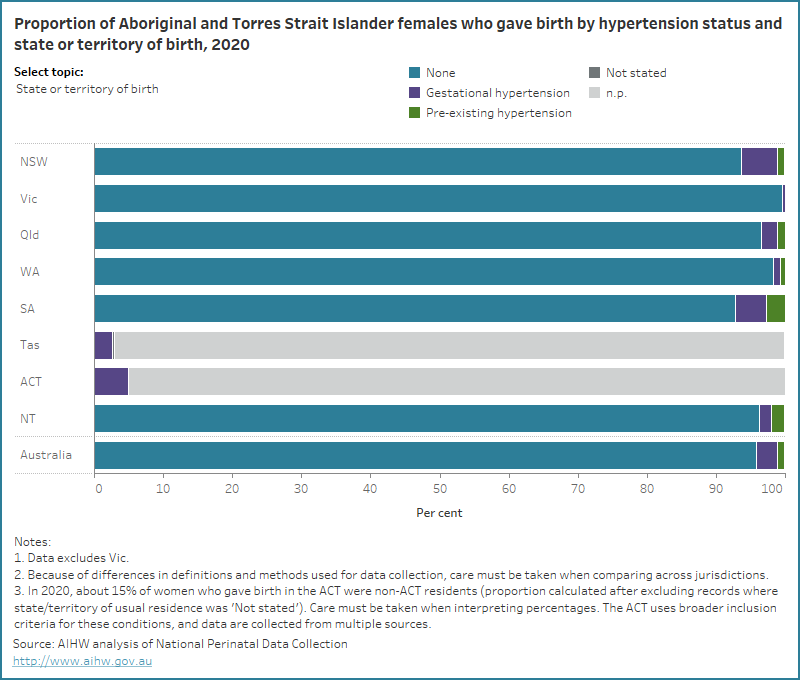

The data visualisation below presents data on the hypertension status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics for 2020.

Figure 5: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander female who gave birth by hypertension status and selected topic for 2020

Bar chart for hypertension type by selected topics. The majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers had no hypertension disorders

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2023), Diabetes: Australian facts, Cat no. CVD 96, Canberra: AIHW.AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2023) Diabetes: Australian facts, Cat no. CVD 96, Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2020), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2020 summary report, Cat. no. IHPF 2, Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2019a), Improving national reporting on diabetes in pregnancy, Cat. no. CDK 13, Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2019b), Incidence of gestational diabetes in Australia, Cat. no. CVD 85, Canberra: AIHW.

Campbell SK, Lynch J, Esterman A & McDermott R (2013) ‘Pre-pregnancy predictors of hypertension in pregnancy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in north Queensland, Australia; a prospective cohort study’, BMC Public Health, 13:138, doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-138.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2020) Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care. Canberra: Australian

Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

Marschner S, Pant A, Henry A, Maple-Brown L, Moran L, Cheung N, Chow C and Zaman S (2023). ‘Cardiovascular risk management following gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a narrative review’, Medical Journal of Australia, doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51932.

Queensland Clinical Guidelines (2021) Hypertension and pregnancy: Guideline no. MN21.13-V9-R26. Queensland Health, Brisbane, accessed 13 October 2022.

Wood A, Graham S, Boyle JA, Marcussuon-Rababi B, Anderson S, Connors C, McIntyre HD, Maple-Brown L and Kirkam R (2021) ‘Incorporating Aboriginal women’s voices in improving care and reducing risk for women with diabetes in pregnancy - A phenomenological study’, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(624), doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04055-2.