Health – selected conditions

Today’s older Australians (aged 65 and over) are generally living longer and healthier lives than those in previous generations. However, many older people live with chronic health conditions. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS) estimated that, in 2017–18, 1.1 million (29%) older people had one chronic condition, just over 831,000 (23%) had 2 and 1.0 million (28%) had 3 or more. The minority of older people had no chronic conditions (730,000, 20%) (ABS 2018a).

This page presents key information about selected health conditions and how they affect older Australians. The information is presented by individual condition or group of conditions. As noted above, many older Australians have several different conditions, and the impact on people’s health care use or wellbeing may be compounded by the number of conditions people have, or the interactions between particular conditions (often referred to as comorbidities). More information on chronic conditions can be found in Chronic disease.

Throughout this page, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus is specified. The ‘Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this page, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented.

Chronic conditions generally have long-lasting and persistent effects. The statistics reported here are based on a selected group of chronic conditions that commonly affect older people, and for which robust data are available. The analysis on chronic conditions does not include all possible chronic conditions. The chronic conditions statistics reported above from the NHS include:

- arthritis

- asthma

- back pain and problems

- cancer

- cardiovascular disease (selected heart, stroke and vascular disease, excluding hypertension)

- chronic kidney disease

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- diabetes

- mental and behavioural conditions

- osteoporosis.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is a term used to describe a range of conditions related to heart, stroke and vascular disease. Cardiovascular disease remains a major health concern in Australia, and it generally has a greater impact on older people (AIHW 2020c).

An estimated 717,800 people aged 65 and over had one or more conditions related to heart, stroke or vascular disease, based on self-reported data from the 2017–18 NHS (AIHW 2020c). The proportion increased with age, with an estimated 16% of people aged 65–74 having heart, stroke and vascular disease, compared with 26% of those aged 75 and over.

A higher proportion of men and a higher proportion of people 75 and over had one or more conditions related to cardiovascular disease (Table 3B.1).

|

Age group (years) |

Males (%) |

Females (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

65–74 |

20 |

12 |

|

75 and over |

32 |

20 |

Source: AIHW 2020c.

Common cardiovascular diseases are coronary heart disease (affecting an estimated 380,000 older people in 2017–18) and stroke (affecting an estimated 276,000 older people) (AIHW 2020c). Again, the prevalence of these diseases was higher for older men compared with women, and increased with age for both men and women (AIHW 2020c).

Cardiovascular disease was a major cause of total burden of disease in older Australians. In 2015, coronary heart disease was the leading cause of disease burden for men aged 65 and over, while for women it was the second leading cause for those aged 75 and over (AIHW 2019).

Cardiovascular disease is also a common cause of hospitalisations. In 2017–18, cardiovascular disease was the principal diagnosis in 387,500 hospitalisations for older Australians, accounting for 66% of all cardiovascular hospitalisations. Hospitalisation rates increased with age, with the highest rates among people aged 85 and over (17,900 hospitalisations per 100,000 population) (AIHW 2020c).

Cardiovascular disease is also a common cause of death. In 2018, there were around 37,400 deaths where cardiovascular disease was the underlying cause among older people (aged 65 and over) (89% of all cardiovascular deaths).

Further information on cardiovascular disease is contained in Heart, stroke and vascular diseases.

Arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions

The musculoskeletal system refers to bones, muscles and joints. As people age, conditions such as arthritis, back problems and osteoporosis become increasingly more common; these can have a profound impact on people’s quality of life and wellbeing.

Arthritis is the most common chronic condition among older Australians. In 2017–18, almost half (49% or 1.8 million) of older people (aged 65 and over) reported arthritis, commonly:

- osteoarthritis (1.2 million people)

- rheumatoid arthritis (193,400 people).

Some 955,000 (26%) older Australians reported back problems (AIHW 2020b).

According to 2015 Australian Burden of Disease Study results, musculoskeletal conditions are a leading cause of non-fatal burden for older people (AIHW 2019). More information about this can be found in Health—status and functioning.

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) refers to dysfunctional or damaged kidneys. At the earlier stages of the disease, people may not feel ill, but in the end stages of the disease, people require dialysis or transplants to stay alive. For various reasons, not all people with end-stage kidney disease receive dialysis or transplant, particularly in the older age groups (AIHW 2020a).

Measured data from the 2011–12 Australian Health Survey – which takes into account biomedical signs as well as self-reporting – showed that the prevalence of biomedical signs of CKD increased rapidly in older ages. The prevalence of CKD was twice as high for people aged 75 and over as for those aged 65–74 (42% and 21%, respectively) and around 7 times as high as for those aged 18–44 (5.5%) and 45–54 (5.6%) (AIHW 2020d). The incidence rate (meaning newly diagnosed cases) similarly increased with age.

In 2017–18, 7 in 10 (70%) of hospitalisations where kidney disease was identified as the principal or additional diagnosis were for people aged 65 and over (AIHW 2020d). The rates of hospitalisations also increased with age. This can reflect the repeated nature of dialysis treatment: older people are more likely to have kidney disease, and people with kidney disease may visit hospital very regularly. The rates of CKD-related hospitalisations for both men and women were highest in those aged 85 and over (19,100 and 11,000 per 100,000 population, respectively) – at least 1.6 times as high as for those aged 75–84 (11,100 and 6,900 per 100,000, respectively) (AIHW 2020d).

Respiratory conditions

Older people are often more vulnerable to respiratory conditions. This broad umbrella term includes both chronic conditions and acute infections (see section on COVID-19 in box below).

A chronic respiratory condition common among older Australians is COPD. This lung disease develops over many years and therefore affects mainly people from middle age onwards. It is characterised by the chronic obstruction of airflow. People with COPD may experience coughing, sputum production, or difficult or laboured breathing. The disease can interrupt daily activities, sleep patterns and the ability to exercise (AIHW 2020f).

According to 2017–18 NHS estimates, 252,000 older Australians reported COPD (including emphysema) as a long-term health condition, representing 7.0% of all older people (7.5% of older men and 6.4% of older women) (ABS 2018b).

The proportion of people with COPD across older age groups was:

- 7.1% of those aged 65–74 (153,000 people)

- 6.6% of those aged 75–84 (74,400 people)

- 6.6% of those aged 85 and over (22,000 people).

Asthma is another common chronic respiratory condition, and its symptoms can overlap with those seen in COPD. According to the 2017–18 NHS, asthma was reported as a long-term health condition by around 1 in 8 (12%, 433,700) older people (9.5% of older men and 14% of older women) (ABS 2018b).

The proportion of older people with asthma across older age groups was:

- 12.6% of those aged 65–74 (274,000 people)

- 12.0% of those aged 75–84 (129,000 people)

- 9.5% of those aged 85 and over (31,600 people) (ABS 2018b).

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

COVID-19 can have a considerable impact on the health of older people because of their weaker immune systems and greater likelihood of having a chronic condition such as dementia, heart disease, diabetes, lung disease and cancer (Wu 2020).

To 14 October 2021, there were just under 15,700 confirmed cases of COVID-19 among people aged 60 and over and just under 1,400 deaths (Department of Health 2021a). From 1 January to 26 September 2021, age groups 60 and over had the lowest rates of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population:

- 60–69 – 132

- 70–79 – 89

- 80–89 – 96

- 90 and over – 99 (Department of Health 2021b).

For information on the use of health services during COVID-19, see Health—service use. For information on how the COVID-19 pandemic affected older Australia’s social engagement, see Social support. For further information on COVID-19 in Australia, see The first year of COVID-19 in Australia: direct and indirect health effects.

Influenza and pneumonia

Influenza and pneumonia also commonly affect older people more than those at younger ages – particularly those who live in permanent residential aged care and who may have dementia. For more information, see Interfaces between the aged care and health systems in Australia – where do older Australians die?.

Dementia

As a term, dementia describes a group of conditions characterised by the gradual impairment of brain function. It is commonly associated with memory loss, but it is not limited to this: people’s ability to speak, think and move can be affected, their behaviour or personality may change. Generally, people’s health and functional abilities decline as the condition progresses. There are many forms of dementia and it is common to have multiple types of dementia at once – known as ‘mixed dementia’. Dementia is more common with advancing age and mainly occurs among people aged 65 and over – but it is not a normal part of ageing.

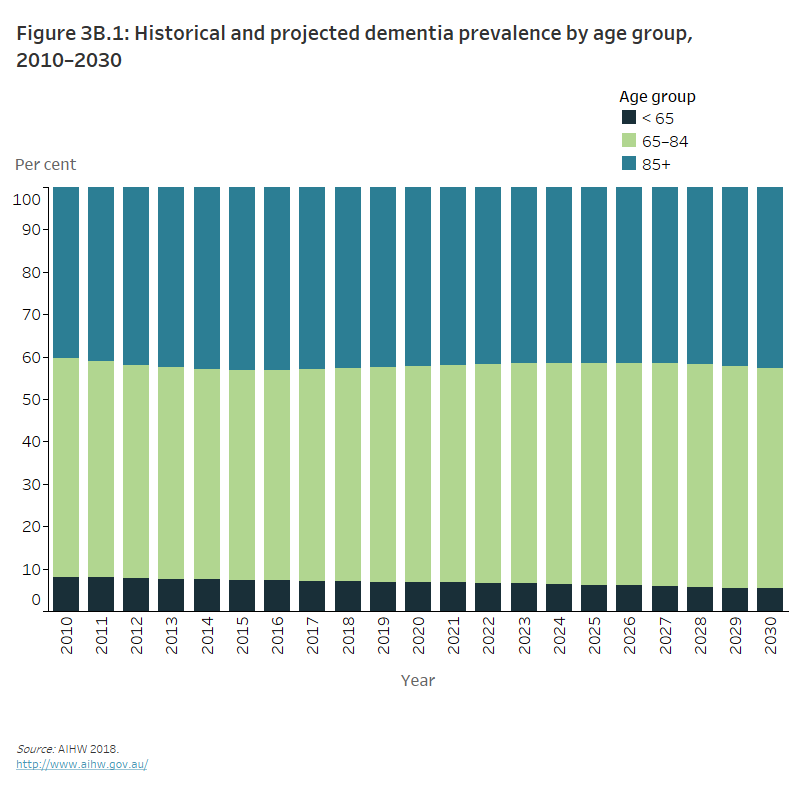

The number of Australians of all ages living with dementia was estimated to be between 400,000 and 459,000 in 2020, but the exact number is unknown (AIHW 2018, 2020a). Some international studies suggest that the incidence of dementia may be decreasing, but the continued growth and ageing of Australia’s population will lead to an increase in the number of people with dementia over time. By 2030, the number of people with dementia is expected to increase to 550,000 (AIHW 2018), with people aged 65–84 making up slightly more than half (52%) of this number (Figure 3B.1).

Figure 3B.1: Historical and projected dementia prevalence by age group, 2010–2030

The stacked column graph shows the proportion of people with dementia is predominately among people aged 65–84 years. Projections suggest that dementia prevalence is likely to remain highest in older age groups, and decrease among people aged under 65 (in 2010 92% of people with dementia were aged over 65, compared to the projected 95% in 2030).

For more information, see Dementia in Australia.

Diabetes

Diabetes is a chronic condition characterised by high levels of glucose (sugar) in the blood. It is caused either by the body’s inability to produce insulin (a hormone produced by the pancreas to control blood glucose levels) or by the body not being able to use insulin effectively. These estimates include people with the following types of diabetes:

- type 1 (non-preventable autoimmune disease mainly developing in childhood)

- type 2 (largely associated with modifiable risk factors but also genetic and family related risk factors)

- type unknown (AIHW 2020h).

The prevalence of diabetes (based on self-reporting) among older people (aged 65 and over) has doubled over the last 2 decades – from 8.5% in 1995 to 16.8% in 2017–18. This increase is likely due to several factors, including an increased prevalence of risk factors, improved public awareness, better detection techniques and improved survival through management strategies.

In 2017–18, 607,700 Australians aged 65 and over self-reported diabetes as a long-term health condition (ABS 2018a). The prevalence of diabetes for those aged 65–74 was more than 3 times as high as for those aged 45–54. Older men aged 65–74 were more likely than women of the same age to report having diabetes (19% compared with 12%, respectively) (AIHW 2020h).

While the self-reported rate of diabetes for Australians aged up to 64 has remained relatively stable since 2001, it has increased for older Australians. In 2017–18, 15% of Australians aged 65–74 self-reported having diabetes, an increase from 13% in 2001. Similarly, in 2017–18, 19% of Australians aged 75 and over self-reported diabetes, an increase from 11% in 2001 (ABS 2018a).

More information about diabetes is available in Health—service use (see ‘Pharmaceutical use’ and ‘Hospitals’), and Health—status and functioning (see ‘Burden of disease’).

Mental health

Mental health is influenced by a combination of psychological, biological and socioeconomic or cultural factors (such as income levels and living conditions) (Slade et al. 2009). Good mental health can support healthy behaviours in old age. In turn, poor mental health can be associated with poor physical health.

Poor mental health can be defined in different ways but commonly it includes mental illnesses such as anxiety disorders, affective disorders (such as depression), psychotic disorders and substance use disorders (AIHW 2020a). People may have experienced poor mental health over their lifetime, or they may have experienced a recent onset; for example, due to stressors such as loss, bereavement or health issues (AIHW 2015).

Mental illness may be more common among particular groups of older Australians, such as older carers, people in hospital and people with dementia (RANZCP 2016; Rickwood 2005). People living in residential aged care are another subgroup at higher risk of poor mental health. At 30 June 2019, of those people living in permanent residential aged care, the majority (87%) were diagnosed with at least one mental health or behavioural condition and 49% had a diagnosis of depression (AIHW 2020l).

For more information on diversity in older Australians, see Culturally and linguistically diverse older people; for more information on their financial and housing situations, see Income and finances and Housing and living arrangements; for more information on older Australians’ experiences of abuse and discrimination, see Justice and safety.

The prevalence of mental illness decreases with age. Using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)—which includes questions about people’s level of nervousness, agitation, psychological fatigue and depression—the 2017–18 ABS NHS showed that:

- almost 7 in 10 (68%) people aged 65 and over reported low levels of psychological distress in the past 4 weeks

- 1 in 5 (19%) reported moderate distress levels

- 10% reported high or very high levels (ABS 2019).

COVID-19 and mental health

Older Australians have been shown to have generally lower levels of anxiety and worry over the course of 2020 than younger Australians. Australian National University research found this in May, August and October 2020. However, between May and August 2020, older people aged 65–74 years had the largest increase in anxiety and worry, up to 57% from 47%. Similarly, older people aged 75 and over were the only age group that saw a significant worsening in psychological distress between May and August 2020 (Biddle et al. 2020).

The ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey showed that, in June 2021, around 1 in 10 (10%) older people (aged 65 and over) reported high or very high distress. However, the majority of older people reported low distress levels (66%). Around 1 in 6 (16%) older people reported feeling nervous at least some of the time in the last 4 weeks (ABS 2021).

For more information, see Household Impacts of COVID-19 survey.

For information on how older Australians use mental health services, see Health—service use. For more information about suicide and self-harm among older people, see Health—status and functioning and Suicide & self-harm monitoring.

Oral health and disease

Oral health relates to the ability to eat, speak and socialise without discomfort or active disease in the teeth, mouth or gums. Oral health generally deteriorates over a person’s lifetime: it can be affected by biomedical risks, as well as clinical conditions and age-related functional impairments, such as increased difficulty with personal care.

Oral disease can in turn have an impact on people’s health and wellbeing more broadly. The 2 main forms of oral disease affect the teeth (dental caries or decay) and gums (periodontal disease). Oral disease also includes conditions such as mouth ulcers, oral cancers, tooth impactions and misaligned teeth, and traumatic injuries to the teeth and mouth (AIHW 2020j).

The proportions of older people with at least one natural tooth who report fair or poor oral health have increased over time (capturing different cohorts of older people):

- For those aged 65–74, the proportion with fair or poor oral health increased from 18% in 2004–06 to 26% in 2017–18.

- For those aged 75 and over, it increased from 18% to 23% (AIHW 2020j).

Among older Australians, the proportion with at least one tooth with untreated decay increased from 22% in 2004–06 to 27% in 2017–18.

Between 2013 and 2017–18, the proportion of older people who had experienced toothache in the past 12 months also increased, from 8.9% to 13%. The proportion of older people who reported feeling uncomfortable with the appearance of their teeth, mouth or dentures in the past 12 months increased from 21.7% in 2013 to 29.1% in 2017–18. Compared with other age groups at both of these time points, older people were the least likely to report feeling uncomfortable with the appearance of their teeth, mouth or dentures (AIHW 2020i).

In 2017–18, the average number of missing teeth for older Australians (aged 65 and over) was 13.7, higher than the 2.5 for young people aged 15–24 (the full adult set is 32). Other selected aspects of oral health and disease were also high for older people (Table 3B.2).

|

|

% |

|---|---|

|

Experienced toothache |

13 |

|

Lost all natural teeth |

15 |

|

Has periodontitis |

59 |

|

Avoided eating some foods due to problems with teeth |

27 |

Note: 'Older Australians' refers to people aged 65 and over.

Source: AIHW 2020i.

Many of these oral health issues and disease have also increased over time. For more information about progress against key performance indicators used to monitor performance of the strategies in Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024, see AIHW (2020i).

Ear health and hearing

Poor ear health and poor hearing can have implications for communication, social participation, independent living and employment (AIHW 2016). Middle-age hearing loss can also be linked to an increased risk of later developing dementia (Livingston et al. 2017). Ear disease and the associated hearing loss can develop over time for many reasons (such as injury, infection or genetic causes) but, for the most part, these are preventable (AIHW 2018).

In 2017–18, an estimated 1 in 3 (34%) people aged 65 and over reported complete or partial deafness as a long-term health condition (ABS 2018b). The 2018 ABS Survey of Disability Ageing and Carers also estimated that among older people, 7.7% (300,000 people) had a main long-term health condition of the ear (diseases of the ear and mastoid process), with a higher proportion of older men affected (11%) than older women (4.7%) (ABS 2019).

Eye health and sight

Chronic eye conditions vary in their presentation, treatment and consequences, but many are commonly experienced by older people. In 2017–18, the majority of people aged 65 and over reported a chronic eye condition (93%, 3.4 million people). The most common chronic eye condition was long-sightedness (62%), followed by short-sightedness (41%), presbyopia (9.6%) – a type of long-sightedness – and cataracts (9.1%) (ABS 2018b).

The prevalence of long-term eye conditions was broadly similar for both older men and women (AIHW 2021b). Looking at selected eye conditions among older Australians between 2007–08 and 2017–18, the prevalence by sex remained relatively stable (Table 3B.3).

|

|

2007–08 |

2017–18 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

Cataracts |

9.0 |

10.2 |

7.4 |

10.6 |

|

Macular degeneration |

4.2 |

6.8 |

4.1 |

4.9 |

|

Glaucoma |

5.2 |

5.0 |

3.5 |

3.8 |

Note: 'Older Australians' refers to people aged 65 and over.

Source: AIHW 2021b.

Chronic pain

Chronic pain is pain that lasts beyond normal healing time after injury or illness. It is a common and complex condition, and the pain experienced may be anything from a mild niggle to debilitating. Older people with chronic pain can be at an increased risk of falling, reduced mobility and disability. In turn, people who experience falls, reduced mobility or disability may be at an increased risk of pain. Pain can also affect people’s ability to look after themselves and remain independent in older age (AIHW 2020e; Eggermont et al. 2014; Stubbs et al. 2014).

Chronic pain is more likely to affect women and older people. In 2016:

- 1 in 5 (20%) people aged 65–74 reported having chronic pain, increasing to 22% of those aged 75–84 and 24% of those 85 and over.

- Among women, chronic pain was 1.8 times as high in those aged 85 and over (28%) as in those aged 45–54 (16%).

- Among men, chronic pain was 1.3 times as high in those aged 85 and over (18%) as in those aged 45–54 (13%) (AIHW 2020e).

For more information, such as hospitalisation for chronic pain, see Chronic pain in Australia.

Where do I find more information?

For more information on health conditions among older Australians, see:

Information about health and aged care service use associated with specific health conditions is located in Health—service use, while information about deaths and burden of disease is located in Health—status and functioning.

ABS 2018a. Diabetes 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018b. National Health Survey: first results, 2017–18, Australia. ABS cat. no. 4364.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2019. Disability, Ageing and Carers: summary of findings, 2018. ABS cat. no. 4430.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2021. Household impacts of COVID-19 survey, June 2021. ABS cat. no. 4940.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2015. Australia’s welfare 2015. Australia’s welfare series no. 12. Cat. no. AUS 189. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 15 June 2021.

AIHW 2016. Australia's health 2016. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 16 March 2021.

AIHW 2018. Australia's health 2018. Cat. no. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 16 March 2021, doi:10.25816/5ec1e56f2548AIHW 2019.

AIHW 2019. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Australian Burden of Disease series no. 19. Cat. no. BOD 22. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020a. Australia’s health 2020. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 16 March 2021.

AIHW 2020b. Back problems. Cat. no. PHE 231. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 15 March 2021.

AIHW 2020c. Cardiovascular disease. Cat. no. CVD 83. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 13 April 2021.

AIHW 2020d. Chronic kidney disease. Cat. no. CDK 16. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 21 January 2021.

AIHW 2020e. Chronic pain in Australia. Cat. no. PHE 267. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020f. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cat. no. ACM 35. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 11 February 2021.

AIHW 2020h. Diabetes. Cat. no. CVD 82. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 17 February 2021.

AIHW 2020i. National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024: performance monitoring report. Cat. no. DEN 232. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 17 February 2021.

AIHW 2020j. Oral health and dental care in Australia. Cat. no. DEN 231. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 17 February 2021.

AIHW 2020l. People’s care needs in aged care. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 15 June 2021.

AIHW 2021a. Dementia deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Cat. no. DEM 1. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2021b. Eye health. Cat. no. PHE 260. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 11 February 2021.

Biddle N, Edwards B, Gray M and Sollis K 2020. Tracking outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, August 2020 – divergence within Australia. Canberra: Australian National University. Viewed 2021.

Department of Health 2021a. Coronavirus (COVID-19) case numbers and statistics. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 15 October 2021.

Department of Health 2021b. COVID-19 Australia: Epidemiology Report 51: Reporting period ending 26 September 2021. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 11 October 2021.

Eggermont LH, Leveille SG, Shi L, Kiely DK, Shmerling RH, Jones RN et al. 2014. Pain characteristics associated with the onset of disability in older adults: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the Elderly Boston Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62(6):1007–1016.

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D et al. 2017. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 390:2673–2734.

RANZCP (Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists) 2016. Professional practice guideline 10: Antipsychotic medications as a treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Melbourne: RANZCP. Viewed January 7 2020.

Rickwood D 2005. Pathways of recovery: preventing further episodes of mental illness. Canberra: National Mental Health Promotion and Prevention Working Party. Viewed 2021.

Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, Whiteford H, Burgess P, Pirkis J et al. 2009. The mental health of Australians 2. Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing. Viewed 2021.

Stubbs B, Binnekade T, Eggermont L, Sepehry AA, Patchay S and Schofield P 2014. Pain and the risk for falls in community-dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 95(1):175–187.

Wu B 2020. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: a global challenge. Global Health Research and Policy 5:27. doi:10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3.