Summary

On this page

Dementia is a term used to describe a group of conditions characterised by gradual impairment of brain function, which may impact memory, speech, cognition (thought), personality, behaviour, and mobility.

There are many forms of dementia, the most common being Alzheimer’s disease – a degenerative brain disease caused by nerve cell death resulting in shrinkage of the brain. It is also common for an individual to have multiple types of dementia, known as ‘mixed dementia’. While the likelihood of developing dementia increases with age, dementia is not an inevitable or normal part of the ageing process. Dementia can also develop in people under 65, referred to as younger onset dementia, and in children, which is known as childhood dementia.

Dementia is a significant and growing health and aged care issue in Australia that has a substantial impact on the health and quality of life of people with the condition, as well as their family and friends. As the condition progresses, the functional ability of an individual with dementia declines, eventually resulting in the reliance on care providers in all aspects of daily living. There is currently no cure for dementia but there are strategies that can assist in maintaining independence and quality of life for as long as possible.

How common is dementia?

In 2023, it was estimated that there were 411,100 (AIHW estimate) Australians living with dementia. Based on AIHW estimates, this is equivalent to 15 people with dementia per 1,000 Australians, which increases to 84 people with dementia per 1,000 Australians aged 65 and over. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Australians with dementia are women.

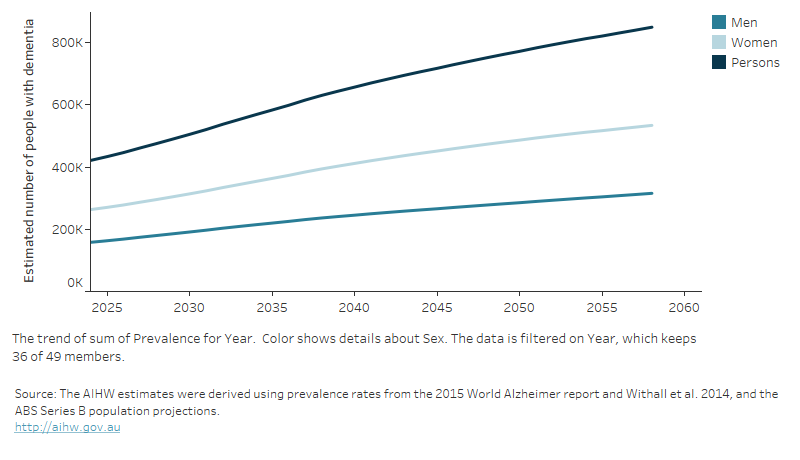

With an ageing and growing population, it is predicted that the number of Australians with dementia will more than double by 2058 to 849,300 (533,800 women and 315,500 men) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Australians living with dementia between 2024 and 2058: estimated number by sex and year

This figure shows the increasing estimated prevalence of dementia between 2010 and 2058.

Measuring dementia prevalence

The exact number of people with dementia in Australia (the ‘prevalence’) is currently not known. Estimates vary because there is no single authoritative data source for deriving dementia prevalence in Australia and different approaches are used to generate estimates. For more information, see What is being done to improve dementia prevalence estimates in Australia?

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated that in 2021, the prevalence of dementia in Australia was 13.2 cases per 1,000 population. This estimate is slightly less than the OECD average of 15.0 per 1,000 population, ranking 12th lowest out of 38 countries (OECD 2023).

For data by age, sex, geographic and socioeconomic area, see Prevalence of dementia.

Risk factors

A range of factors are known to contribute to the risk of developing dementia and may affect the progression of symptoms. Some risk factors can’t be changed, such as age, genetics and family history. However, there are health behaviours that can increase or decrease the risk of developing dementia (known as ‘modifiable risk factors’).

High levels of education, physical activity and social engagement are all protective against developing dementia, while obesity, smoking, high blood pressure, hearing loss, depression and diabetes are all linked to an increased risk of developing dementia (Livingston et al. 2017).

For more information about risk factors, see What puts someone at risk of developing dementia?

Impact

Dementia is the second leading cause of death in Australia

In 2021, dementia was the second leading cause of death in Australia, accounting for just under 15,800 deaths (or 10% of all deaths). Dementia was the leading cause of death for women and the second leading cause for men, after coronary heart disease.

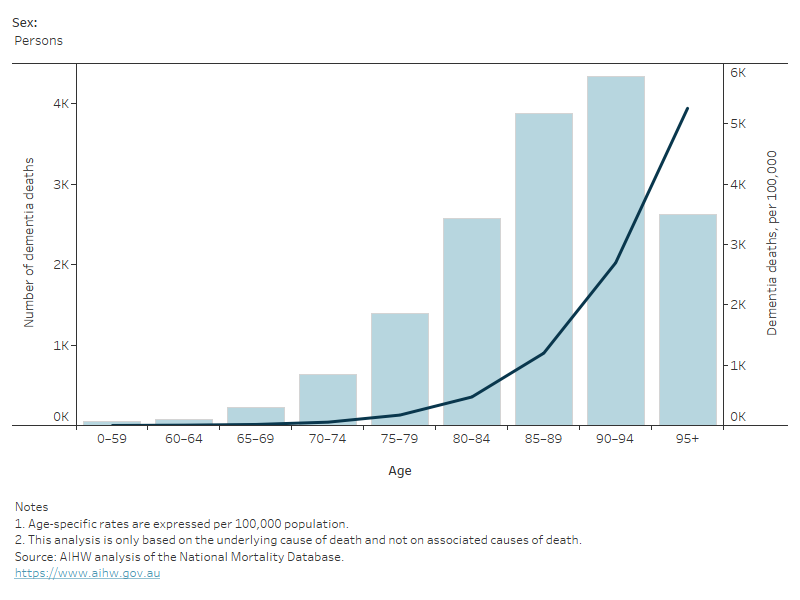

The number of deaths due to dementia increased from 10,780 deaths in 2012 to 15,800 deaths in 2021. The age-standardised rate, which accounts for differences in the age and sex structure of a population, rose between 2012 and 2021, from 38 to 41 deaths per 100,000 Australians. The rate of deaths due to dementia by age and sex was highest among men and women aged 95 and over, reaching just over 4,000 and 5,700 per 100,000 population, respectively (Figure 2).

For more information, see Deaths due to dementia.

Figure 2: Deaths due to dementia: number and age-specific rates, by age and sex, 2021

This figure shows that age-specific death rates increased with age, with women having higher rates than men.

Impact of COVID-19 on people with dementia

People with pre-existing chronic conditions, such as dementia, have a greater risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19. Fatal COVID-19 outbreaks have involved many people with dementia. Pre-existing chronic conditions were reported on death certificates for 11,075 deaths due to COVID-19, registered by 30 April 2023 in Australia. Of these deaths, over 30% had dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease) recorded (ABS 2023). COVID-19 was an associated cause of death for a further 677 deaths due to dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease).

For more information on COVID-19 deaths released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), see COVID-19 Mortality in Australia: Deaths registered until 31 January 2024.

Dementia is a leading cause of burden of disease

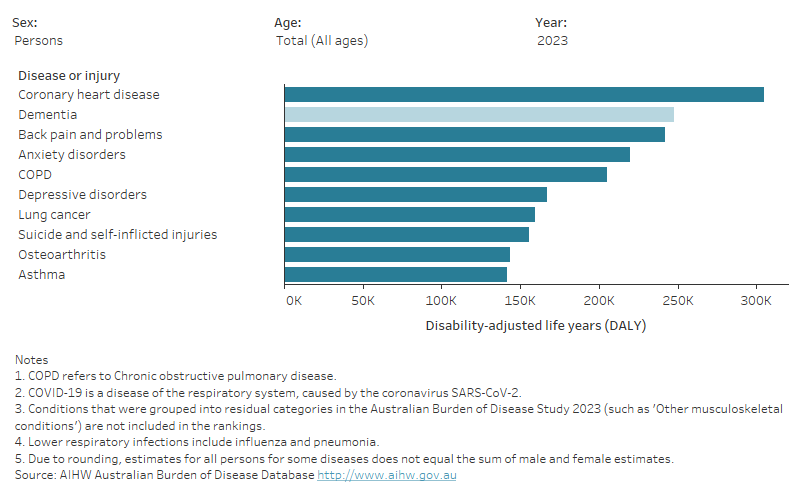

Burden of disease refers to the quantified impact of living with and dying prematurely from a disease or injury and is measured using disability-adjusted life years (DALY). One DALY is equivalent to one year of healthy life lost.

Dementia was the second leading cause of burden of disease in Australia in 2023, behind coronary heart disease. However, it was the leading cause of burden for women as well as for Australians aged 65 and over. The total burden of dementia was almost 248,000 DALY, with 59% of burden attributable to dying prematurely and 41% from the impacts of living with dementia (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Leading 10 causes of disease burden (DALY) in Australia, by sex and age, 2015, 2018, 2022 and 2023

This figure shows that dementia was the second leading cause of disease burden in Australia, and was the leading cause of disease burden for women.

Around 43% of the overall dementia burden in 2018 could have been avoided if exposure to 6 lifestyle risk factors (overweight including obesity, physical inactivity, tobacco smoking, high blood pressure in midlife, high blood plasma glucose levels, and impaired kidney function) were reduced.

For detailed information on burden attributable to specific risk factors, see Burden of disease due to dementia.

Treatment, management and support

Primary health care services

Services provided by general practitioners (GPs) and other medical specialists are crucial in diagnosing and managing dementia. If a GP suspects dementia, they typically refer the patient to a qualified specialist, such as a geriatrician, or to a memory clinic for a comprehensive assessment (Dementia Australia 2020).

How is dementia diagnosed?

There is no single conclusive test available to diagnose dementia, and obtaining a diagnosis often involves a combination of comprehensive cognitive and medical assessments.

Identifying the type of dementia at the time of diagnosis is important to ensure access to appropriate treatment and services. However, there are many forms of dementia with symptoms in common, often making diagnosis a lengthy and complex process involving multiple health professionals – see How is dementia diagnosed?

Data on GP and specialist services across Australia are a major enduring gap for dementia monitoring. However, recent advancements in data linkage have enabled the examination of these services – see Primary health care services.

In 2020–21, around half of all services claimed under the Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) by people with dementia were for GP consultations (42% for people in the community and 58% for people living in permanent residential aged care).

The second most common MBS service used by people with dementia were pathology services, accounting for 32% of services among those living in the community, and 29% among those living in permanent residential aged care.

Among people with dementia living in the community, more than 70% of people aged 65–84 years had at least one specialist visit in 2020–21. Specialist attendances including general medicine, geriatric medicine, neurology and psychiatry were more common among people with dementia compared to people without dementia living in the community.

Among people living in permanent residential aged care, specialist and allied health service use was generally lower among people with dementia compared to people without dementia.

For information about patterns of health service use among people with younger onset dementia see Younger onset dementia: new insights using linked data.

Dementia-specific medications

Although there is no cure for dementia, there are 4 medications subsidised through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, that may alleviate some of the symptoms and slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

In 2021–22, there were over 658,000 prescriptions dispensed for dementia-specific medications to just under 68,700 Australians with dementia aged 30 and over. There was a 51% increase in scripts dispensed for dementia-specific medications between 2012–13 and 2021–22.

People with dementia may experience changed behaviours, such as aggression, agitation and delusions, commonly known as behaviours and psychological symptoms of dementia. Non-pharmacological interventions are recommended to manage these symptoms, but antipsychotic medicines may be prescribed as a last resort.

In 2021–22, antipsychotic medications were dispensed to about one-fifth (20%) of the 68,700 people who had scripts dispensed for dementia-specific medication.

For information on medicine types, see Prescriptions for dementia-specific medications.

Hospitalisations

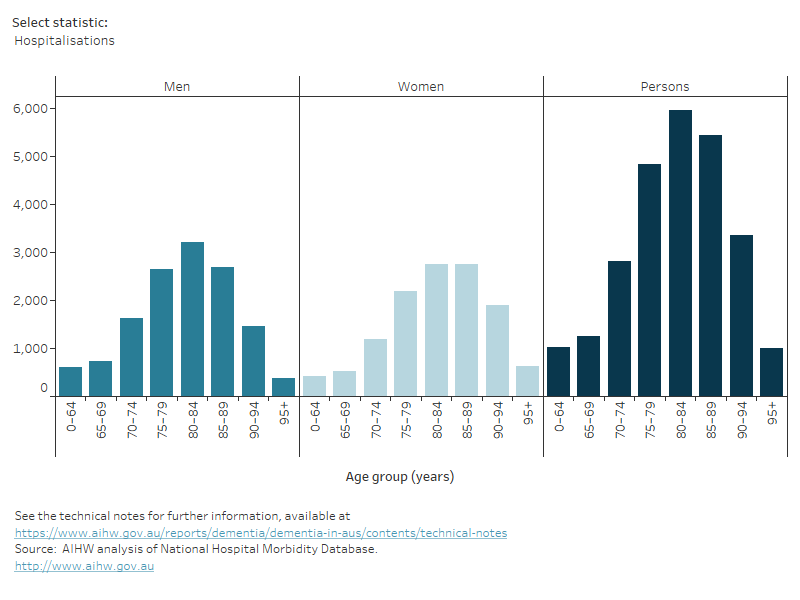

In 2021–22, there were more than 11.6 million hospitalisations in Australia (AIHW 2023). Of these, dementia was the main reason for admission for about 25,700 hospitalisations, which is equivalent to 2 out of every 1,000 hospitalisations.

For people with dementia, the average length of stay was more than 5 times as long as the average for all hospitalisations (15 days and 2.7 days, respectively). Of the hospitalisations due to dementia, 63% of patients were aged 75–89, with the number of hospitalisations increasing with age up to 80–84 years, then decreasing in the older age groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Hospitalisations due to dementia, by age and sex, 2021–22

This figure shows various measures for hospitalisations due to dementia, including number, rate, bed days and length of stay.

Data presented in this section refer to hospitalisations due to dementia, that is, when dementia was recorded as the principal diagnosis. However, understanding hospitalisations with dementia, that is, all hospitalisations with a record of dementia, whether as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, also provides important insights into the wide-ranging conditions that can lead people living with dementia to use hospital services.

For information on hospitalisations with dementia, as well as data by state and territory and dementia type, see Hospital care.

Aged care services

Aged care services are an important resource for both people with dementia and their carers. Services include those provided in the community for people living at home (home support and home care), and residential aged care services for those requiring permanent care or short-term respite stays.

In 2021–22, there were over 242,000 people living in permanent residential aged care, and more than half (54% or about 131,000) of these people had dementia.

For detailed information on the services and initiatives available, see Aged care and support services used by people with dementia.

How do people with dementia access aged care services?

The My Aged Care system coordinates access to a range of government-subsidised services for older Australians who require care and assistance. After an initial screening, an aged care assessment is completed to establish an individual’s needs and types of services that may help.

In 2021–22, just over 37,100 Australians who completed an aged care assessment (either a comprehensive or home support assessment) had dementia recorded as a health condition. This equates to 9.3% of people who completed an aged care assessment that year. Of the aged care assessments undertaken by people with dementia, just over 4 in 5 (81%) were comprehensive assessments (for people with complex and multiple care needs).

Health and aged care expenditure on dementia

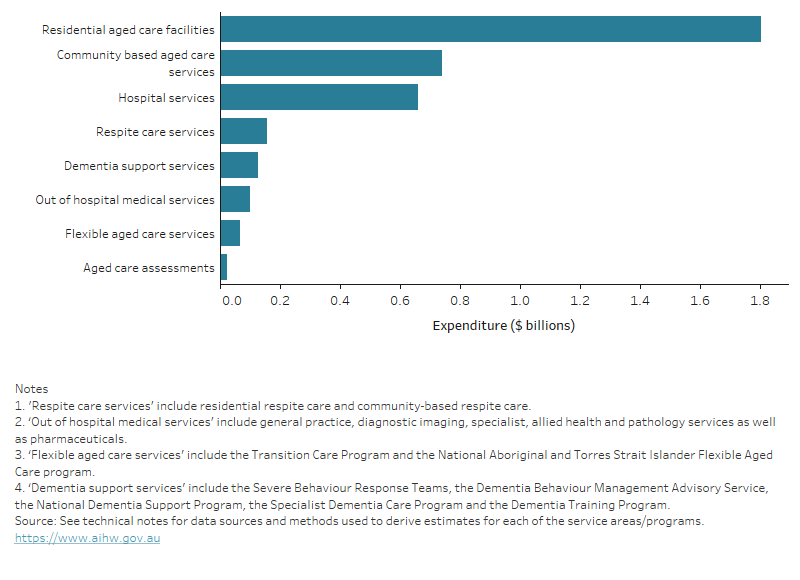

Australia’s response to dementia requires economic investment across health, aged care and welfare sectors. It is estimated that almost $3.7 billion of health and aged care spending in 2020–21 was directly attributable to the diagnosis, treatment and care of people with dementia.

Residential aged care services accounted for the largest share of expenditure (49% or $1.8 billion), followed by community-based aged care services (20% or $741 million) and hospital services (18% or $662 million) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Health and aged care spending directly attributable to dementia by broad service area, 2020–21

This figure shows how the $3 billion dollars of dementia expenditure was divided across 8 broad health and aged care service areas.

For detailed information of spending on aged care, health, hospital and support services, see Health and aged care expenditure on dementia.

Carers

The level of care required for people with dementia depends upon individual circumstances, but likely increases as dementia progresses. Carers are often family members or friends of people with dementia who provide ongoing, informal assistance with daily activities.

The AIHW estimates that in 2023 there were at least 140,900 informal primary carers of people with dementia. Among primary carers of people with dementia, 3 in 4 (75%) were female and 1 in 2 (50%) were caring for their partner with dementia.

Caring can be a rewarding role with 38% of primary carers of people with dementia reporting feeling closer to the care recipient.

Caring can also be physically, mentally, emotionally, and economically demanding. According to the ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) 2018, among carers of people with dementia:

- 1 in 2 (47%) provided an average of 60 or more hours of care per week

- 3 in 4 (76%) reported one or more physical or emotional impacts of the role

- 1 in 4 (23%) reported that they needed more respite care to support them

- 1 in 2 (52%) experienced financial impacts since taking on the role.

Further findings from this survey can be found in Carers and care needs of people with dementia.

Dementia data gaps

Australia’s dementia statistics are derived from a variety of sources including administrative data, survey data and epidemiological studies. As each data source has incomplete coverage of people with dementia, it is difficult to accurately report how many Australians are living with dementia. This limits the ability to examine impacts of dementia on individuals with the condition, their carers and support networks, as well as the community and national health and aged care systems more broadly.

For more information, see Dementia data gaps and opportunities and the National Dementia Data Improvement Plan 2023–33.

Estimating the incidence (new dementia cases in a given period) and prevalence (total cases) of dementia in Australia is vital to evaluating the current and future impacts of the condition, as well as for policy and service planning. There are several factors in the diagnostic process that affect our ability to estimate the number of Australians living with dementia, including:

- an often lengthy diagnosis process for reasons such as not recognising symptoms, a delay in seeking help, limited access to specialists or complexity of diagnostic processes

- no single conclusive diagnostic assessment for dementia

- lack of national GP or specialist data collections with dementia-specific diagnostic information.

There are ongoing efforts to improve the accuracy of these estimates, such as through the utilisation of data linkage, electronic health records and the development of a national dementia clinical quality registry.

Around 1% of all dementia diagnoses in Australia are childhood dementia caused by over 70 rare genetic disorders (Childhood Dementia Initiative 2020). Most cases of childhood dementia are fatal before adulthood (Dementia Support Australia 2022).

There are limited data available on childhood dementia both within Australia and internationally. Increased awareness and research of childhood dementia is needed to improve the quality of life for children with dementia.

Dementia statistics within Australia are largely sourced from hospital, aged care and cause of death data, likely providing a skewed view towards moderate and severe dementia. There are considerable gaps in primary health care data and data about use of services by people with dementia living in the community. Further, there is a lack of timely data on dementia disease expenditure. Without this information, it is difficult to determine the demand for dementia services and plan for economic costs to health and social systems.

Understanding patient experiences of people with dementia and their carers is important to assess the quality of care within the health and aged care systems. There is a lack of information on these experiences, and improvements are needed to understand these qualitative aspects to improve quality of care and outcomes for those living with dementia.

For more information, see the National Dementia Data Improvement Plan 2023–33.

There are considerable gaps in national data on carers of people with dementia in Australia. The ABS SDAC 2018 provides the most up-to-date national information on carers. However, this survey is limited to collecting self-reported information from co-resident carers only for people with dementia and, further, likely under-identifies the number of people with dementia (particularly people with mild dementia living in the community). As a result, it is challenging to comprehensively understand how many Australians provide care to people with dementia and what their unmet needs may be.

Australians living with dementia come from diverse backgrounds and have unique and variable needs for services and support. National data on people with dementia in specific population groups are limited and further research is needed.

First Nations people

Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people, the rate of dementia is estimated to be 3–5 times as high as rates for Australia overall. However, improvements are needed in the representation of First Nations people in key datasets to support better dementia prevalence estimates.

There are also limited data on Indigenous-specific health and aged care services. Improving data in these areas will help to identify how dementia is understood and managed by First Nations people and improve the development of culturally appropriate and effective policies and services.

Due to sampling issues, data on First Nations carers of people with dementia and/or carers of First Nations people with dementia are not available as part of the ABS SDAC.

People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

For people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, attitudes towards, as well as access to, aged care and support services need to be considered.

Based on the ABS SDAC 2018, 1 in 2 (47%) people with dementia who were born in non-English–speaking countries and were living in the community relied upon informal assistance only (compared to 1 in 3 (30%) people who were born in English speaking countries). This may reflect a preference for informal care or may be due to challenges in accessing suitable services. Gaps in data limit the understanding of how individual CALD communities may differ in their experiences of disease, attitudes surrounding dementia and carers, and access to and utilisation of services.

For information on population groups of interest that may benefit from a more specific focus within dementia care, see Dementia in priority groups.

Where do I go for more information?

- For more AIHW reports on this topic, visit Dementia.

- For detailed dementia statistics, see chapters of Dementia in Australia.

- For dementia information, education, advocacy and resources, see Dementia Australia.

- For support services and information, see Dementia Support Australia.

- For information on ageing and carers from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, see Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: summary of findings, 2018.

- For information on the Australian adult population’s attitudes and knowledge of dementia and dementia risk reduction, see Australia’s Dementia Awareness Survey.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019) Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018– Explanatory notes, ABS website, accessed 19 January 2022.

ABS (2023) COVID-19 Mortality in Australia: Deaths registered until 30 April 2023, ABS website, accessed 19 June 2023.

AIHW (2023) Admitted patient care 2021–22: Australian hospital statistics, AIHW website, accessed 29 June 2023.

Childhood Dementia Initiative (2020) Childhood Dementia: the case for urgent action, Childhood Dementia website, accessed 19 January 2022.

Dementia Support Australia (2022) Childhood Dementia Support, Dementia Support Australia website, accessed 19 January 2022.

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D et al. (2017) ‘Dementia prevention, intervention, and care’, The Lancet, 390:2673–734, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2023) Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicator, 2023 edn, OECD Publishing, doi:10.1787/19991312.