Preparedness for release

People who have been incarcerated are often at their most vulnerable on release, and many of the health improvements made during their time in prison can quickly erode.

Release from prison might cause trauma and emotional distress, and increase the likelihood of harmful substance use, and other risk behaviours. So death rates from most causes of death, but particularly preventable causes, increase dramatically on release (Binswanger et al. 2013; Bukten et al. 2017; Forsyth et al. 2018; Spitall et al. 2019; Thomas et al. 2016).

The rapid churn of people through the prison system means that prisoner health is public health (WHO 2012). This is particularly true with short-term incarceration, and most people in prison are in prison for relatively short periods (ABS 2023). As well, the risk of re-offending is often higher when people are released from prison without medical and support plans in place (Phillips and Lindsay 2011).

Instituting comprehensive and consistent release procedures, and ensuring continuity of health care between prison clinic and community service providers, are essential for the health of people leaving prison, as well as for the health of the community.

Prison dischargees were asked how prepared they felt about their upcoming release from prison.

Almost 9 in 10 (88%) prison dischargees said they were prepared for their upcoming release from prison (Indicator 3.2.10).

The majority (88%) of dischargees reported that they felt either prepared (44%) or very prepared (44%), with only 12% reporting they felt unprepared or very unprepared for release from prison.

First Nations dischargees (90%) were slightly more likely than non-Indigenous dischargees (87%) to report feeling prepared or very prepared for their upcoming release.

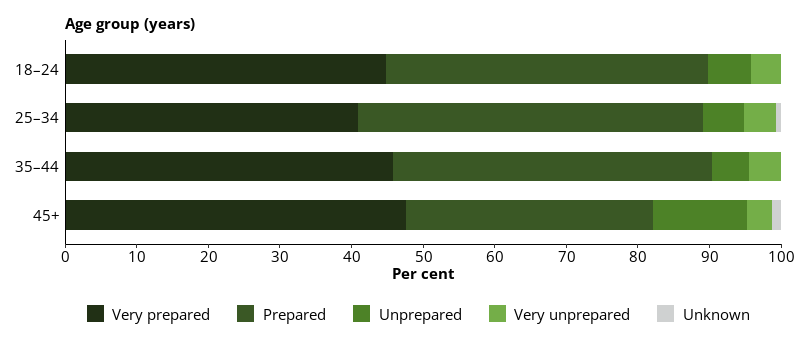

Prison dischargees aged under 45 were more likely to report feeling prepared or very prepared for release from prison (90%) than those aged 45 and over (82%) (Figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4: Prison dischargees, self-reported level of preparedness for release, by age, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023) Prisoners in Australia, 2022, ABS website, accessed 25 May 2023.

Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR and Stern MF (2013) ‘Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009’, Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9):592–600, doi:10.7326/0003–4819–159–9–201311050–00005.

Bukten A, Stavseth MR, Skurtveit S, Tverdal A, Strang J and Clausen T (2017) ‘High risk of overdose death following release from prison: variations in mortality during a 15-year observation period’, Addiction, 112(8):1432–1439, doi:10.1111/add.13803.

Forsyth SJ, Carroll M, Lennox N and Kinner SA (2018) ‘Incidence and risk factors for mortality after release from prison in Australia: a prospective cohort study’, Addiction, 113(5):937–945, doi:10.1111/add.14106.

Phillips LA and Lindsay M (2011) ‘Prison to society: a mixed methods analysis of coping with re-entry’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(1):136–154, doi:10.1177/0306624X09350212.

Spittal MJ, Forsyth S, Borschmann R, Young JT and Kinner SA (2019) ‘Modifiable risk factors for external cause mortality after release from prison: a nested case-control study’, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(2):224–233, doi:10.1017/S2045796017000506.

Thomas EG, Spittal MJ, Heffernan EB, Taxman FS, Alati R and Kinner SA (2016) ‘Trajectories of psychological distress after prison release: implications for mental health service need in ex-prisoners’, Psychological Medicine, 46(3):611–621, doi:10.1017/S0033291715002123.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2012) ‘The new European policy for health – Health 2020: policy framework and strategy’, WHO, Copenhagen.