Homelessness

There are clear links between homelessness and health, with homeless people having mortality rates that are an estimated 2–5 times higher than for the general population, especially from suicide and unintentional injuries. Homeless people also have higher rates of infectious diseases, chronic conditions, mental health issues, and alcohol and other drug use disorders. Similar to people in prison, they also experience accelerated ageing (Fazel et al. 2014).

Homelessness not only refers to those sleeping on the streets, but also includes those with unstable housing – such as improvised dwellings or tents, supported accommodation, temporarily living with other households, and staying in boarding houses or other temporary lodging.

Data from the 2021 Australian Census of Population and Housing show that an estimated 122,500 people (0.5% of the general Australian population) were homeless on Census night (ABS 2023). Of these people, an estimated 7,600 (less than 0.1% of the Australian population) were sleeping rough in improvised dwellings or tents, or sleeping outside (ABS 2023).

Accommodation for prison entrants before prison

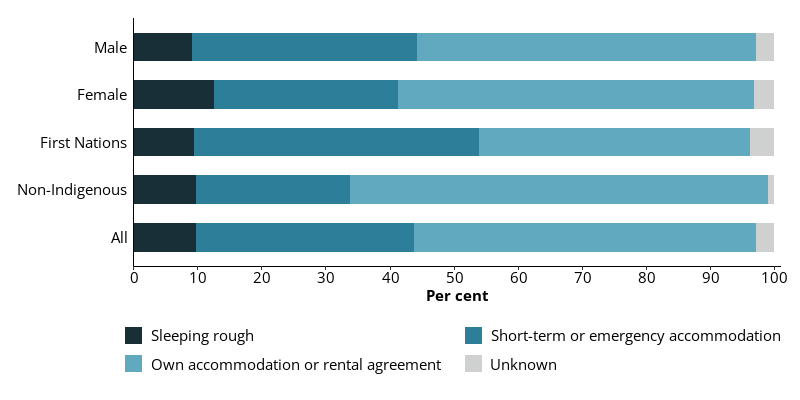

More than 2 in 5 (43%) prison entrants reported that they were homeless (including staying in short-term or emergency accommodation) during the 4 weeks before prison (Indicator 2.1.10).

Prison entrants were around 100 times more likely to be homeless than people in the general community. More than 1 in 3 (36%) prison entrants were in short-term or emergency accommodation, and 1 in 10 (10%) were in unconventional housing or sleeping rough (Figure 8.8).

Of 183 First Nations prison entrants, over a half (54%) had experienced homelessness in the 4 weeks before entering prison: 9.8% had experienced sleeping rough and 46% had experienced short-term or emergency accommodation in the 4 weeks prior to entering prison (Figure 8.8).

One-third (33%) of non-Indigenous prison entrants had experienced homelessness in the 4 weeks before entering prison while two-thirds (66%) had not experienced homelessness (Figure 8.8).

Figure 8.8: Prison entrants, accommodation type in the 4 weeks before prison, by sex and Indigenous identity, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection, and not the entire prison population.

- Multiple responses were allowed.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

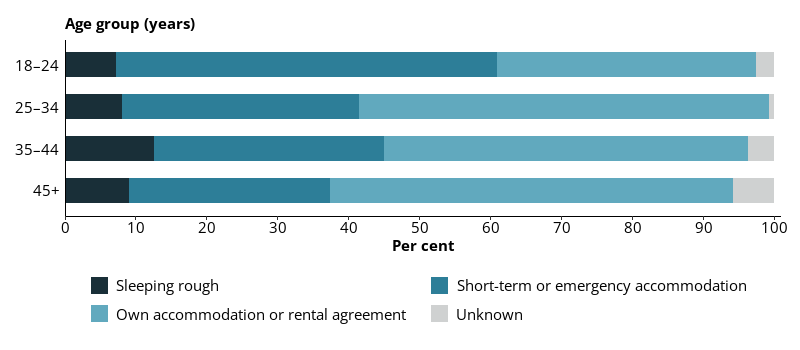

Prison entrants aged 18–24 were the group most likely to have experienced homelessness in the 4 weeks before entering prison (61%), while people aged 45 and over were the least likely to have experienced homelessness (37%) (Figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9: Prison entrants, accommodation type in the 4 weeks before prison, by age, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection, and not the entire prison population.

- Multiple responses were allowed.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Accommodation expectations of prison dischargees once released

Finding suitable stable accommodation is a major concern for people about to be released from prison, especially for those with no family support.

In 2021–22, 2.4% of all adult clients of specialist homelessness services had come from a custodial setting (including prison), youth justice detention centres, and immigration detention centres. The majority were males (54%) aged 20–44 (59%). They were also more likely than other adult homelessness services clients to need assistance with drug and alcohol counselling (26% compared with 11% of all adult clients) (AIHW 2022).

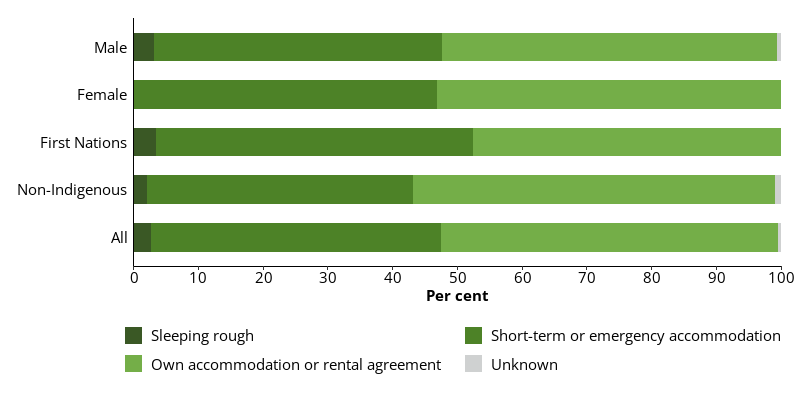

Almost a half (48%) of prison dischargees expected to be homeless (including in short-term and emergency accommodation) once released (Indicator 2.1.11).

Almost a half of prison dischargees (45%) were planning to sleep in short-term or emergency accommodation and 2.8% expected to sleep rough on release from prison (Figure 8.10).

About a half (52%) of prison dischargees had their own stable accommodation arranged, where they were either the owners or named on a lease (Figure 8.10).

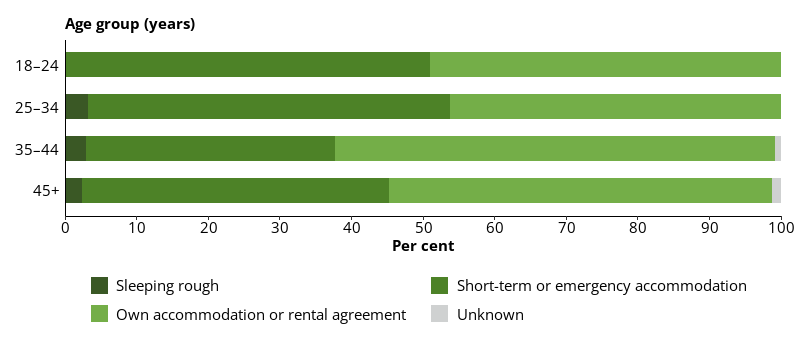

Prison dischargees aged 35–44 were the most likely age group to report having their own accommodation (61%) while those aged 25–34 were the least likely to report having their own accommodation (46%) (Figure 8.11).

Figure 8.10: Prison dischargees, accommodation type expected on release from prison, by sex and Indigenous identity, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

Figure 8.11: Prison dischargees, accommodation type expected on release from prison, by age, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023), Estimating homelessness: Census, ABS website, accessed 21 April 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022) Specialist Homelessness Services Collection data cubes 2011–12 to 2021–22, AIHW website, accessed 24 April 2023.

Fazel S, Geddes JR and Kushel M (2014) ‘The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations’, The Lancet 384:1529–1540.