Clients exiting custodial arrangements

On this page

Key findings: Clients exiting custodial arrangements, 2022–23

Access to stable accommodation is critical for successful reintegration into the community and people exiting custody can be highly vulnerable to not having adequate and stable accommodation (AIC 2018). People discharged from prison can face stigma associated with a history of incarceration and discrimination from landlords and potential employers (Schetzer and StreetCare 2013). Prisoners applying for parole may experience difficulties securing appropriately located and affordable accommodation, leading to refusal of parole or breach of parole conditions and subsequent return to prison (Schetzer and StreetCare 2013).

Many adults entering prison had previous experiences of homelessness, with more than 2 in 5 (43%) homeless in the 4 weeks before prison (AIHW 2023). Almost one-third (30%) of surveyed women in prisons were in short-term or emergency accommodation in the 4 weeks before prison (AIHW 2023).

The inter-relationship between housing insecurity and imprisonment and re-imprisonment is relatively well established (summarised in Martin et al. 2021). Post-release housing assistance can be an effective measure in addressing the imprisonment–homelessness cycle. Critically, rates of re-imprisonment have shown to be less for ex-prisoners with complex needs who receive public housing compared with those who receive private rent assistance only (Martin et al. 2021).

Young people leaving youth detention can also become entangled in a cycle of detention and homelessness. Housing instability and homelessness are often cited as drivers of an increasing youth detention population, with young people remanded in detention due to a lack of appropriate options for accommodation (Cunneen et al. 2016, Richards 2011). Among those released from detention, 8% of young people accessed homelessness support within 12 months of release (AIHW 2012).

Moreover, people with a history of youth justice supervision remain vulnerable to homelessness in adulthood. Adults who were previously under youth justice supervision are almost twice as likely to sleep rough or in squats (Bevitt et al. 2015). In comparison with people who have only experienced specialist homelessness services, those who have experienced both these services and youth justice supervision were more likely to report having a drug and/or alcohol issue, and to end specialist homelessness services support sleeping rough (AIHW 2016).

On June 30 2022, there were 40,590 prisoners in Australian prisons, a 6% increase from 30 June 2021 (ABS 2023). Almost half (48%) of prison dischargees expected to be homeless once released, with 45% of prison dischargees planning to sleep in short-term or emergency accommodation and 2.8% expected to sleep rough on release from prison (AIHW 2023). Having stable accommodation helps people exiting prison to transition successfully into society and reduces the likelihood of reoffending. Currently, 45% of prison dischargees return to prison with a new sentence within two years (SCRGSP 2022a).

People exiting institutions and care into homelessness are a national priority homelessness cohort identified in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement which came into effect on 1 July 2018 (CFFR 2018) (see Policy section for more information).

Reporting clients exiting custodial arrangements in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

In the SHSC, a client is identified as leaving a custodial setting if, in their first support period during the reporting period, either in the week before or at presentation:

- their dwelling type was adult correctional facility, youth/juvenile justice correctional centre or immigration detention centre

- they identified transition from custodial arrangements as a reason for seeking assistance, or main reason for seeking assistance, or

- their source of formal referral to the agency was youth or juvenile justice correctional centre or adult correctional facility.

Some of these clients were still in custody at the time they began receiving support. Note, in the SHSC, it is not possible to distinguish between clients who have received assistance without leaving an institutional setting and those who may have left an institutional setting but returned prior to the end of support.

Children aged under 10 cannot be charged with a criminal offence in Australia. Therefore, clients aged under 10 who were identified as exiting from adult correctional facilities or youth/juvenile justice correctional centres have been excluded.

For more information, see Technical notes.

In 2022–23 (Supplementary tables EXIT.1 and HIST.EXIT):

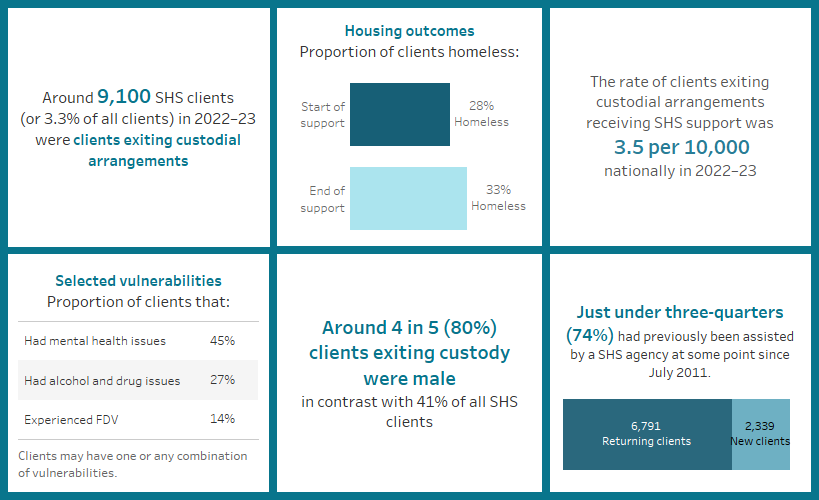

- There were around 9,100 SHS clients who exited custodial arrangements, equating to 3.3% of all SHS clients.

- There were an additional 130 SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements compared with 2021–22.

Client characteristics

Figure EXIT.1: Key demographics, SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements, 2022–23

This interactive visualisation describes the characteristics of around 9,100 clients existing custodial arrangements who received SHS support in 2022–23. Most clients were male. Over a quarter of clients were Indigenous. Victoria had the greatest number of clients and had the highest rate of clients per 10,000 population. The majority of clients had previously been assisted by a SHS agency since July 2011. Most were at risk of homelessness at the start of support. Most were in major cities.

Labour force status

In 2022–23, the majority of clients exiting custodial arrangements were not in the labour force (53%). More than two-fifths (44%) were unemployed (that is, seeking work) and only 2.7% were employed (Supplementary table EXIT.7).

Of the clients with known labour force status, female clients were more likely to be employed part-time (3.2% of all female clients) than males (1.1%). Females (49%) were also more likely to be unemployed than males (43%).

Selected vulnerabilities

Clients exiting custodial arrangements may face challenges that make them more vulnerable to experiencing homelessness. The vulnerabilities presented here include family and domestic violence, a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

In 2022–23, of the 9,100 clients exiting custodial arrangements, more than half (55%) reported experiencing one or more vulnerabilities (Supplementary table CLIENTS.47), lower than all SHS clients (59%). Around half (45% or around 4,100 clients) reported a current mental health issue, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

Figure EXIT.2: Clients existing custodial arrangements, by selected vulnerability characteristics, 2022–23

This interactive bar graph shows the number of SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements also experiencing additional vulnerabilities, including family and domestic violence, having a current mental health problem and problematic drug and/or alcohol use. The graphs shows both the number of clients experiencing a single vulnerability only, as well as combinations of vulnerabilities, and presents data for each state and territory.

Service use patterns

On average, clients exiting custodial arrangements received a median of 43 days of support in 2022–23, down from 47 days in 2021–22. The average number of support periods per client was 1.9 support periods per client in 2022–23 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.48).

New or returning clients

In 2022–23 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.42):

- Of the 9,100 clients exiting custodial arrangements, 26% (around 2,300 clients) were new to SHS agencies and 74% (almost 6,800 clients) were returning clients, having previously been assisted by a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in July 2011. The proportion of returning clients was one of the highest among all SHS client groups and higher than all SHS clients (63%; Supplementary table CLIENTS.2).

- New clients exiting custodial arrangements were more likely to be under 18 (8.6%, compared with 3.5% of returning clients).

- A higher proportion of females were returning clients (80% of female clients, compared with 73% of males).

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2022–23, the main reasons for seeking assistance among clients exiting custodial arrangements were (Supplementary table EXIT.5):

- transition from custodial arrangements (69% or 6,300 clients)

- housing crisis (6.6% or about 600 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (5.3% or 480 clients).

Clients exiting custodial arrangements who were at risk of homelessness at first presentation were more likely to identify transition from custodial arrangements as the main reason for seeking assistance (82%, compared with 42% experiencing homelessness) (Supplementary table EXIT.6).

Clients exiting custodial arrangements who were experiencing homelessness at first presentation were more likely to report housing crisis (13%, compared with 3.6% at risk) or inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (13%, compared with 2.0% at risk) as the main reason for seeking assistance.

Services needed and provided

Clients exiting custody were more likely than all SHS clients to need services including (Supplementary tables EXIT.2, CLIENTS.24):

- assistance with challenging social/behavioural problems (15%, compared with 11%), with 83% receiving this service

- drug/alcohol counselling (8.3%, compared with 3.0%), with 41% receiving this service

- employment assistance (9.6%, compared with 6.5%), with 73% receiving this service.

Figure EXIT.3: Clients exiting custodial arrangements, by services needed and provided, 2022–23

This interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the services needed by clients exiting custodial arrangements and their provision status. Short-term housing was the most needed service and assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction was the most provided service. Long-term housing was the least provided service.

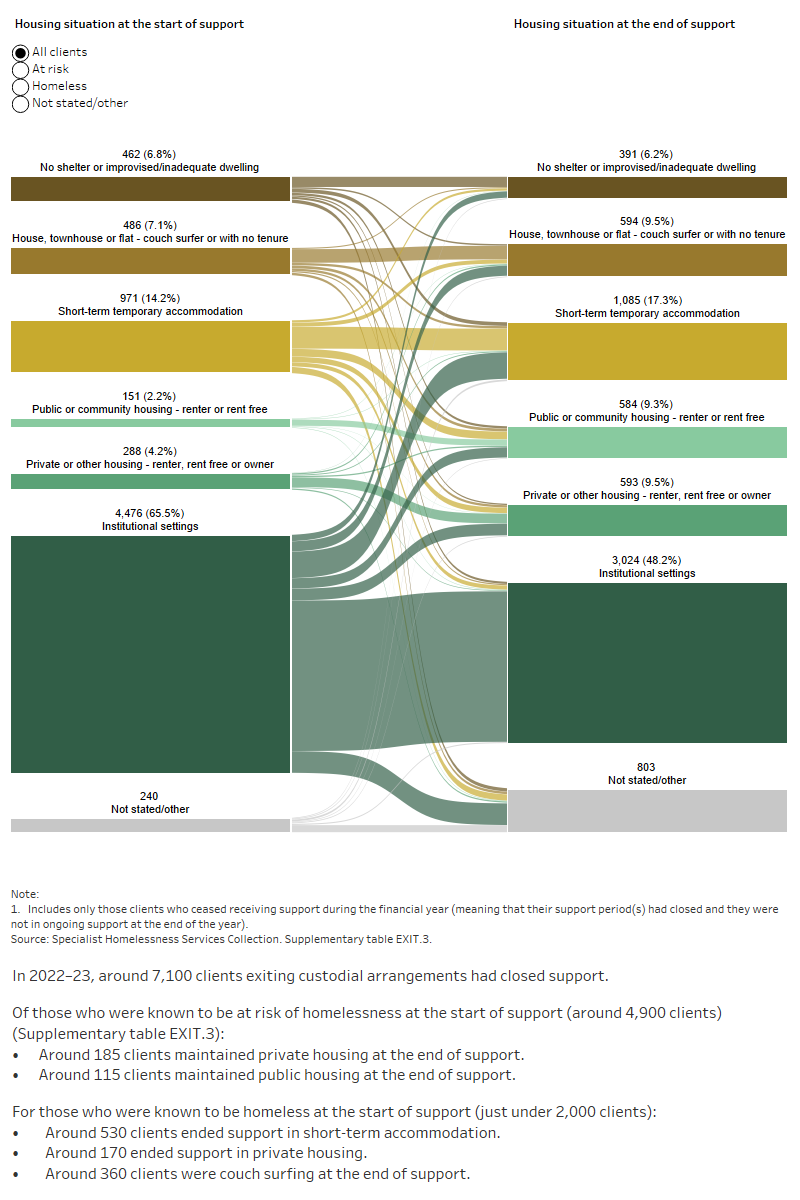

Housing situation and outcomes

Outcomes presented here highlight the changes in clients’ housing situation at the start and end of support. That is, the place they were residing before and after they were supported by a SHS agency. The information presented is limited only to clients who have stopped receiving support during the financial year, and who were no longer receiving ongoing support from a SHS agency. In particular, information on client housing situations at the start of their first period of support during 2022–23 is compared with the end of their last period of support in 2022–23. As such, this information does not cover any changes to their housing situation during their support period.

In 2022–23, for clients exiting custodial arrangements:

- One-third (33%) of clients were experiencing homelessness at the end of support, an increase from 28% at the beginning of support, reflective of the housing challenges faced by people leaving prison. Most of those experiencing homelessness at the end of support were living in short-term temporary accommodation (around 1,100 clients) (Supplementary table EXIT.3).

- Among clients exiting custodial arrangements, the number living in public or community housing increased by about 430 clients at the end of support and the number of clients living in private or other housing increased by almost 315 clients (Supplementary table EXIT.4).

These trends demonstrate that known housing outcomes at the end of support can be challenging for clients transitioning from institutional settings. While some clients progressed towards more positive housing solutions, many remained in institutional settings, returned to institutional settings or were in temporary accommodation at the end of support.

Figure EXIT.4: Housing situation for clients exiting custodial arrangements with closed support, 2022–23

This interactive Sankey diagram shows the housing situation (including rough sleeping, couch surfing, short-term accommodation, public/community housing, private housing and institutional settings) of clients exiting custodial arrangements with closed support periods at first presentation and at the end of support. The diagram shows clients’ housing situation journey from start to end of support. Most started and ended support in institutional settings.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023) Prisoners in Australia, 2022, ABS website, accessed 19 September 2023.

Australian Institute of Criminology (2018) Supported housing for prisoners returning to the community: A review of the literature, AIC website, accessed 29 September 2022.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) The health of people in Australia’s prisons 2022, AIHW website, accessed 16 November 2023.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016) Vulnerable young people: interactions across homelessness, youth justice and child protection: 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2015, AIHW website, accessed 31 October 2022.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2012) Children and young people at risk of social exclusion: links between homelessness, child protection and juvenile justice, AIHW website, accessed 31 October 2022.

Bevitt A, Chigavazira A, Herault N, Johnson G, Moschion J, Scutella R, Tsent Y-P, Wooden M and Kalb G (2015) Journeys Home research report no. 6: complete findings from waves 1 to 6, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, Melbourne.

Council on Federal Financial Relations (2018) National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, CFFR website, accessed 9 October 2020.

Cunneen C, Goldson B and Russell S (2016) ‘Juvenile justice, young people and human rights in Australia’, Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 28(2): 173–189, doi:10.1080/10345329.2016.12036067.

Martin C, Reeve R, McCausland R, Baldry E, Burton P, White R and Thomas S (2021), Exiting prison with complex support needs: the role of housing assistance, AHURI Final Report No. 361, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

Richards K (2011), ‘Trends in juvenile detention in Australia’, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice, catalogue number 416: 1-8, Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Government, accessed 31 October 2022.

Schetzer L and StreetCare (2013) Beyond the prison gates: the experiences of people recently released from prison into homelessness and housing crisis, Public Interest Advocacy Centre, accessed 31 October 2022.

Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, (2022) Report on Government Services 2022, Part C Table CA.4, Productivity Commission, Canberra.