Clients leaving care

Those who are not in stable accommodation after leaving health or social care arrangements find themselves particularly vulnerable to homelessness. Clients are identified as leaving care if, in their first support period during 2015–16 (either the week before or at the beginning of the support period):

- their dwelling type was: hospital, psychiatric hospital or unit, disability support, rehabilitation, aged care facility; or

- their reason for seeking assistance was: transition from foster care/child safety residential, or transition from other care arrangements.

In 2015–16, almost 7,000 clients or 2% of specialist homelessness service clients were identified as leaving care.

Key findings in 2015–16

- Client numbers rose 13% from 2014–15 to around 7,000, due predominantly to increased numbers of clients in New South Wales. This growth rate was higher than that of the general SHS population (9%).

- Housing crisis was the most common main reason clients leaving care sought assistance from homelessness agencies (22%, a rise of 2 percentage points from 2014–15). In line with this, accommodation services were needed by 3 in 4 clients (76%).

- The proportion of clients provided with accommodation and the length of accommodation decreased in 2015–16; 48% received accommodation and half of these clients received 42 nights or fewer.

- At the end of support 1 in 4 (24%) clients were housed in private or other housing (renter, rent free or owner), 1 in 4 (24%) were living in institutional settings, and 1 in 4 (24%) (considered homeless) were living in short-term or emergency accommodation.

Clients leaving care: 2011–12 to 2015–16

The proportion of clients leaving care in the SHS population and subsequently seeking assistance from specialist homelessness services has remained relatively stable over the 5 years of the SHS collection to 2015–16. Key trends identified in this client population over these 5 years are:

- Taking into account changes in population size, the rate of service use by clients leaving care has increased (Table LCare Trends.1).

- While males consistently made up the majority of clients leaving care, the age of these clients has increased over time; the age group with the highest proportion has increased from 25–34 in earlier years to 35–44 in the past 2 years.

- Engagement with homelessness services is increasing for this group. Both the length of support and number of support periods have increased over the 5 years from a median of 52 days and 1.7 support periods per client leaving care to 60 days and 1.9 support periods suggesting that these clients are presenting with complex needs.

| 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of clients (proportion of all clients) | 4,654 (2) | 5,542 (2) | 5,573 (2) | 6,084 (2) | 6,869 (2) |

| Rate (per 10,000 population) | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| Housing situation at the beginning of first support period (proportion of all clients) | |||||

| Homeless | 28 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 30 |

| At risk of homelessness | 72 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 70 |

| Length of support (median number of days) | 52 | 62 | 62 | 58 | 60 |

| Average number of support periods per client | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Proportion receiving accommodation | 59 | 57 | 54 | 52 | 48 |

| Median number of nights accommodated | 38 | 45 | 48 | 44 | 42 |

| Proportion of a client group with a case management plan | 67 | 69 | 71 | 71 | 70 |

| Achievement of all cases management goals (per cent) | 16 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 17 |

Notes

- Rates are crude rates based on the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June of the reference year.

- The denominator for the proportion achieving all case management goals is the number of client groups with a case management plan. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant National supplementary table.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2011–12 to 2015–16.

Characteristics of clients leaving care 2015–16

- Of clients leaving care in 2015–16, 1 in 5 were leaving a psychiatric hospital (21%), with the next most common rehabilitation (17%) or hospital (15%).

- The reason 42% (or 2,900) of these clients sought assistance was because they were transitioning from foster care/ child safety residential placements or other care arrangements.

- The majority of clients leaving care in 2015–16 were males (56%) and 22% of the male clients were aged 35–44 years. Female clients tended to be younger with nearly 1 in 4 aged 18–24 (24%).

- The majority (59%) were living alone when they sought assistance, the same as in 2014–15.

Services needed and provided

3 in 4

clients leaving care (76%) needed accommodation services, much higher than the general SHS population (56%).

54%

of all clients leaving care arrangements needed short-term or emergency accommodation, compared with 38% of the general population.

44%

of clients leaving care requested medium-term/transitional housing, higher than the general SHS population (27%) and these clients were more likely to be provided with accommodation (38% of those who requested it compared with 34%, respectively).

43%

requested long-term housing, but this was only able to be provided to 6% of the clients who needed it.

Other services most commonly needed by these clients were material aid/brokerage (39%), transport (39%) and living skills/personal development (37%). These services were needed by higher proportions of clients leaving care than clients in the general SHS population (35%, 22%, and 20%, respectively).

Housing outcomes

For those clients leaving care whose support had ended:

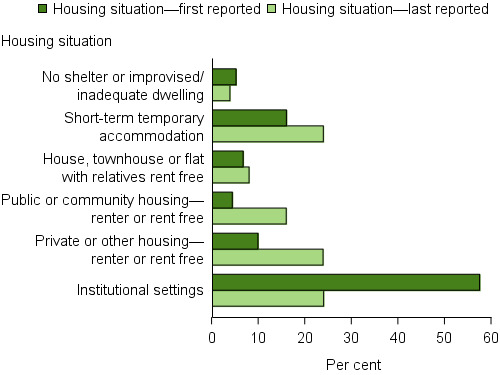

- Fifty-eight per cent (or nearly 2,700 clients) were living in institutional settings at the beginning of their support (Table LCARE.4). This proportion decreased to 24% at the end of support (Figure LCARE.1).

- Over a quarter (28%, or nearly 1,300 clients) were classified as homeless at the beginning of their support period, with the majority (57%) living in short-term emergency accommodation.

- At the end of support, the proportion of these clients classified as homeless had actually increased (from 28% to 36%; almost 1,500 clients homeless). This increase reflects clients leaving an institutional setting (considered at risk, rather than homeless) and subsequently becoming homeless. Most commonly, those homeless were living in short-term or emergency accommodation (24%) when support ended.

- Private or other housing was the most common housing situation at the end of support, increasing 14 percentage points to 24%.

Figure LCARE.1: Clients leaving care, by housing situation at beginning of support and end of support, 2015–16

Notes

- The SHSC classifies clients living with no shelter or improvised/ inadequate dwelling, short-term temporary accommodation, or in a house, townhouse, or flat with relatives (rent free) as homeless. Clients living in public or community housing (renter or rent free), private or other housing (renter or rent free), or in institutional settings are classified as housed.

- Proportions include only clients with closed support at the end of the reporting period.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services 2015–16, National Supplementary Table LCARE.4.