Health behaviours and risk factors of Australia's females

Page highlights

- Which risk factors cause the most ill health and premature deaths in females?

- 34% of ill health and premature death among females could have been potentially prevented by avoiding or reducing exposure to certain risk factors.

- The leading risk factors contributing to the most total disease burden among females are tobacco, overweight (including obesity), dietary risk factors and high blood pressure.

- Tobacco, alcohol and other drugs

- Tobacco is the leading preventable cause of ill health and premature death in females, responsible for 8.0% of total disease burden.

- Around 1 in 11 (8.2%) Australian females smoke daily.

- Around 7.5% of females used an e-cigarette or vaping device at least once in their lifetime.

- About 1 in 8 (13%) females drank more than 10 standard drinks per week.

- Over 4 in 10 (41%) females have tried at least one illicit drug in their lifetime.

- Overweight and obesity

- Overweight (including obesity) is the 2nd leading preventable cause of ill health and premature deaths in females, responsible for 7.8% of total disease burden.

- 3 in 5 (60%) of Australian females are living with overweight or obesity.

- Diet

- Dietary risk factors are the 3rd leading preventable cause of ill health and premature death in females, responsible for 4.1% of total disease burden.

- About 1 in 10 (9%) Australian females meet the recommended daily fruit and vegetable intake guidelines, in 2020–21.

- Physical inactivity

- 59% of Australian females are sufficiently physically active.

- Only 25% of females do enough strength or toning activities on 2 or more days per week.

- Occupational exposures and hazards

Deaths from traumatic injuries in the workplace are rare in females – 6 out of 169 traumatic injury fatalities. - Violence against females

Almost 2 in 5 (39%) Australian females have experienced physical and/or sexual violence since the age of 15.

A person’s health and wellbeing are influenced by many factors, including individual health behaviours, socioeconomic factors and the environment in which they live. Health behaviours including physical activity, a well–balanced diet, a safe occupation and maintaining a healthy body weight reduces the risk of poor health. Risk factors such as smoking tobacco, alcohol consumption, using illicit substances or being exposed to violence, increase the likelihood of poor health.

Around 34% of ill health and premature death in Australian females was potentially preventable in 2018 – that is, it could have been potentially prevented had exposure to certain risk factors been reduced or avoided (AIHW 2023a).

The leading risk factors contributing to ill health and premature deaths in Australia among females are tobacco use, followed by overweight and obesity, all dietary risks, and high blood pressure in 2018 (AIHW 2022k). Risk factors that have the most impact on the burden of disease for females vary across age groups (Figure 8).

For more information see Burden of disease.

Figure 8: Leading risk factor contribution to ill health and premature death (attributable DALY per 1,000 population; proportion of DALY), females aged 15 and over, 2018

Notes:

- DALY = Disability Adjusted Life–Year. This is a measure of healthy life lost, either through premature death or living with disability due to ill health. It is the basic unit used to measure the burden of a disease.

- Note: For age groups under 25, many risk factors were not measured due to data limitations of linked diseases among these age groups.

- Partner violence = Intimate partner violence; Blood glucose = High blood glucose; Blood pressure = High blood pressure.

Source: AIHW analysis of AIHW 2022k

Tobacco smoking

Tobacco was the leading preventable cause of ill health and premature deaths for females, responsible for 8.0% of the total burden of disease in Australia in 2018. Tobacco is linked to a number of common and serious health conditions, including many respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers (AIHW 2021b).

Tobacco use contributed to around 8,800 deaths among females (11.5% of all female deaths). The burden of tobacco use is 2.7 times higher for females in the lowest socioeconomic areas when compared with the highest areas (AIHW 2021b).

The latest data pooled from multiple ABS surveys report that 8.2% of females are current daily smokers, while 0.9% are current smokers who smoke less than daily (ABS 2022f).

Smoking rates for current daily smokers varies by age group among females, peaking in the age group of 55–64 at 12%, with rates being lowest in females aged 75 and over (2.3%) (Figure 9) (ABS 2022f).

The proportion of females who smoke daily varies by population groups. After adjusting for differences in age structures:

- females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas were almost 4 times as likely to smoke daily as females in the highest socioeconomic areas (19% and 5.2%, respectively), in 2017–18 (Figure 10) (ABS 2019a)

- females living in Outer regional and remote areas were 1.6 times as likely to smoke daily than males in Major cities (16% and 9.9%, respectively), in 2017–18 (Figure 10) (ABS 2019a)

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females were 3 times as likely to smoke daily as non-Indigenous females, with 37% of Indigenous females aged 15 and over smoking daily, according to 2018–19 data (AIHW 2020a, AIHW 2020b)

- the proportion of Indigenous females who are current smokers was the highest in Remote and very remote areas (51%) compared with non-remote areas, such as Major cities (30%), Inner regional (40%) and Outer regional (41%) areas (AIHW 2020a).

For more information, see Smoking.

Figure 9: Current daily smoking status and age group (percentage), females, 2020–21

Source: ABS 2022f. See Table S8 for data and footnotes.

Figure 10: Daily smoking by socioeconomic group and remoteness areas (percentage), females, 2017–18

Source: ABS 2019a. See Table S8 for data and footnotes.

Electronic cigarettes/e-cigarettes or vapes

Electronic cigarettes/e-cigarettes or vapes are personal vaping devices where users inhale vapour rather than smoke. The inhaled vapour usually contains flavourings and may contain nicotine as well.

In 2020–21, around 7.5% of females reported using an e-cigarette or vaping device at least once in their lifetime (ABS 2022m). Just over 1 in 5 (22%) of females aged 18–24 had tried an e-cigarette or vaping device, the highest proportion of any female age group.

Around 1.6% of females currently use an e-cigarette or vaping device in 2020–21. Females aged 18–24 (4.8%) and 25–34 (3.6%) have the highest proportions of those currently using an e-cigarette or vaping device (ABS 2022m).

Alcohol

Alcohol was the 6th leading preventable cause of ill health and premature mortality in females, responsible for 2.6% of ill health and death in Australia in 2018. Alcohol use is linked to alcohol use disorders, mental health, accidental poisoning, cancer, heart disease, chronic liver disease, and injuries.

Alcohol contributed to around 2,400 deaths (3.2% of all female deaths). The burden of alcohol use is 1.7 times higher for females in the lowest socioeconomic areas when compared with the highest areas (AIHW 2021b).

To reduce the risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury, it is recommended females should drink no more than 10 standard drinks a week, and no more than 4 standard drinks on any one day. The less you drink, the lower your risk of harm from alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

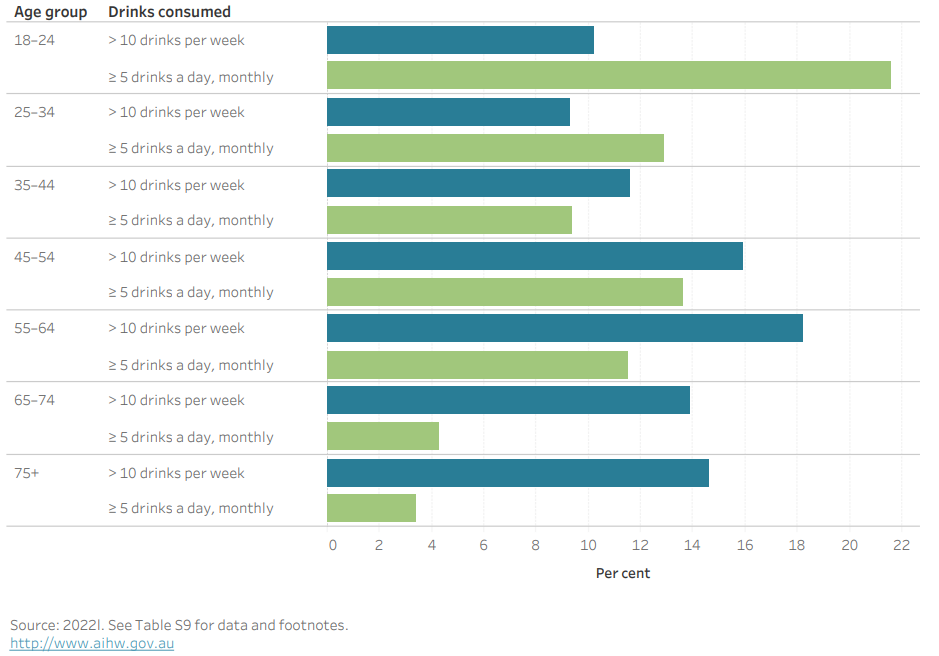

Reporting against these guideline recommendations, in 2020–21 (ABS 2022l):

- 13% of females exceed the guideline by consuming more than 10 standard drinks per week, and of these 71% are drinking more than 14 drinks.

- 11% of females exceed the guideline by consuming 5 or more standard drinks on a single day, at least monthly in the last 12 months.

- The percentage of females who exceed 10 standard drinks per week is highest in those aged 55–64 (18%), while the percentage who exceed 5 drinks on a single day at least monthly is highest in the youngest age group of 18–24 (22%) (Figure 11).

After adjusting for differences in age structures, the proportion of females exceeding the lifetime alcohol risk guidelines (drinking more than 2 standard drinks per day) is (Figure 12) (AIHW 2022a):

- 1.4 times higher in the highest socioeconomic areas (9.9%) compared to the lowest socioeconomic areas (6.9%) based on the 2017–18 NHS (Figure 11)

- 1.5 times higher in females living in Outer regional and remote areas (12%) compared with females living in Major cities (8.2%).

Figure 11: Alcohol drink consumption by age group (percentage) against the recommended guideline, females, 2020–21

Source: 2022l. See Table S9 for data and footnotes.

Figure 12: Lifetime alcohol use by socioeconomic group and remoteness areas (percentage), females, 2017–18

Source: AIHW 2022a. See Table S9 for data and footnotes.

Illicit use of drugs

Illicit use of drugs includes use of illegal drugs, non-medical use of pharmaceuticals and inappropriate use of other substances, such as naturally occurring hallucinogens.

Illicit drug use is estimated to contribute to 1.8% of ill health and premature mortality in females; in females aged 25–44, it is the 2nd leading preventable cause of ill health and death (Figure 7). Illicit drug use includes opioid use (responsible for 0.5% of ill health), amphetamine use (0.4%), unsafe injecting practices (0.4%), cannabis use (0.2%), as well as cocaine and other illicit drug use (both 0.1%) (AIHW 2021b). Illicit drug use is linked to accidental poisoning, drug use disorders, infectious disease, chronic liver disease, mental health conditions and road traffic injuries.

Illicit drug use contributes to around 840 deaths among females (1.1% of all female deaths). The burden of illicit drug use is almost 2 times higher for females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas when compared with the highest socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2021b).

Among females, 41% have used at least one illicit drug at some point in their lifetime. Females aged 40–49 are the most likely to have used an illicit drug in their lifetime (53%) (AIHW 2020b).

In the previous 12 months, 13% of all females used an illicit drug, with the greatest use in females aged 20–29 (25%), compared with 6.3% of females aged 60 or over (AIHW 2020c).

For more information, see Alcohol, tobacco and other drugs in Australia, National Drug Strategy Household Survey report 2019.

For more information on the disease burden due to illicit drug use, see Burden of disease.

Overweight (including obesity) is the 2nd leading preventable cause of ill health and premature mortality for females, responsible for 7.8% of ill health and premature death in Australia in 2018 (AIHW 2021b). Overweight (including obesity) is linked to 30 diseases for females, including 17 types of cancer, 4 cardiovascular diseases, 3 musculoskeletal conditions, type 2 diabetes, dementia, asthma, and chronic kidney disease.

Overweight (including obesity) contributed to around 7,800 deaths among females (10% of all female deaths) and this has the greatest impact on those aged over 65 years. The burden of overweight (including obesity) is 2.3 times higher for females in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with the highest socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2021c).

For more information on the disease burden due to overweight (including obesity), see Burden of disease.

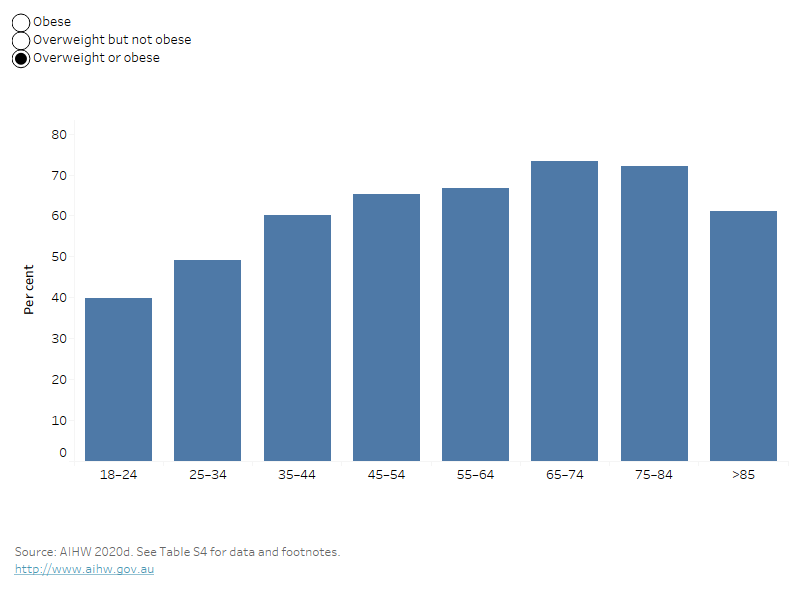

According to 2017–18 NHS data:

- 3 in 5 (60%) Australian females are living with overweight or obesity.

- 3 in 10 (30%) are living with overweight (but not obesity).

- 3 in 10 (30%) are living with obesity.

Overweight and obesity is more common in older age groups. Around 3 in 4 females (73%) aged 65–74 are living with overweight or obesity, compared with 2 in 5 females (40%) aged 18–24 (AIHW 2023e) (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Prevalence of various weight classifications by age group (percentage), females, 2017–18

By selecting the various weight classifications in this bar chart, the prevalence of the individual classification will be shown across age groups.

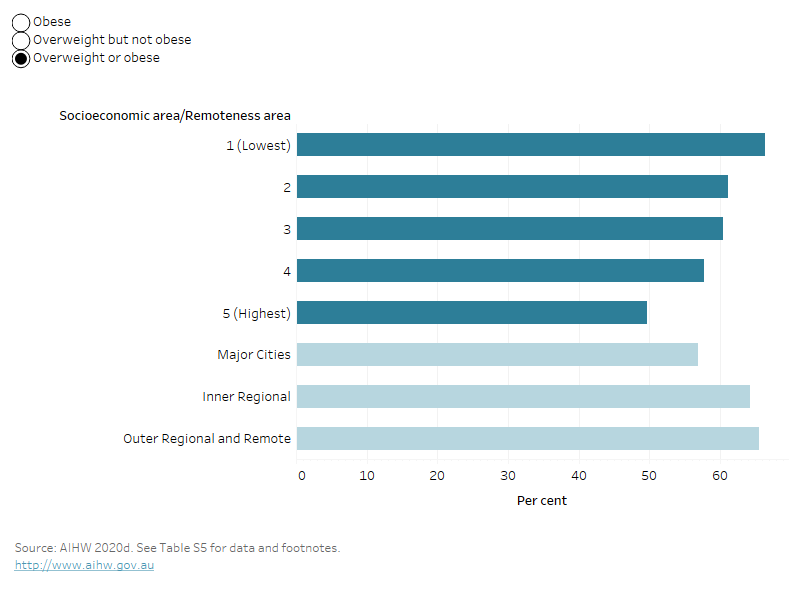

The proportion of females who are living with overweight or obesity varies for some population groups. After adjusting for age (AIHW 2023d):

- females living in Outer regional and remote areas are 1.2 times as likely to be living with overweight or obesity as females in Major cities (66% and 57%, respectively)

- females in the lowest socioeconomic areas are 1.3 times as likely to be living with overweight or obesity as females in the highest socioeconomic areas (66% and 50%, respectively) (Figure 14).

For more information see Overweight and obesity.

Figure 14: Prevalence of various weight classifications by socioeconomic group and remoteness areas (percentage), females, 2017–18

By selecting the various weight classifications in this bar chart, the prevalence of the individual classification will be shown across different socioeconomic areas.

Waist circumference

Waist circumference is another common measure of overweight and obesity. For females, a waist circumference above 80cm is associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications, and above 88cm a substantially increased risk (AIHW 2023c).

Among Australian females, 2 in 3 (66%) have a high-risk waist circumference; that is, one associated with an increased or substantially increased risk of metabolic complications (Figure 15). The average waist circumference for females in 2017–18 is 88 cm (ABS 2018a).

A high-risk waist circumference is more common in older females:

- Around 4 in 5 females aged 75 and over (84%) have a high-risk waist circumference.

- Around 2 in 5 females aged 18–24 (37%) have a high-risk waist circumference.

Figure 15: Waist circumference by health risk category (percentage), females, 2017–18

Source: ABS 2018a. See Table S6 for data and footnotes.

Management of overweight and obesity

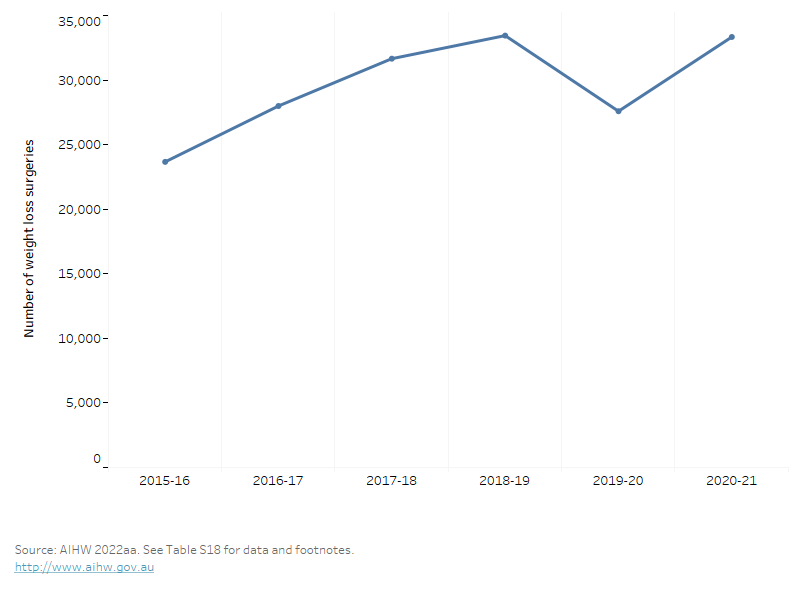

While excess weight is commonly managed using dietary intervention and exercise, for those who are living with morbid obesity, or conditions related to their excess weight, weight loss surgery may be appropriate. Weight loss surgery (bariatric surgery) aims to help patients lose weight and lower the risk of medical problems by restricting the amount of food, or altering the process of digestion so that fewer calories are absorbed.

Females accounted for 80% of procedures for weight loss surgery (over 33,300 procedures) in 2020–21. This was an increase from 23,700 procedures in 2015–16 to 31,600 procedures in 2017–18 (Figure 16) (AIHW 2022y).

Figure 16: Waist loss surgeries, females, 2015–16 to 2020–21

This line graph shows that weight loss surgeries have been increasing over time until 2019-20 when there was a decrease, possibly due to pandemic restrictions, however this recovered quickly as restrictions eased.

Dietary risks factors are the 3rd leading preventable cause of ill health and premature death in females, responsible for 4.1% of ill health and premature death in Australia in 2018. Dietary risk factors include components where adequate amounts in the diet are required to prevent disease and diets where excessive consumption contributes to disease development. The 12 individual dietary risks were:

- a diet low in: fruit and vegetables, milk, nuts and seeds, whole grains and high fibre cereals, legumes, polyunsaturated fat, and fish and seafood

- a diet high in: sodium, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red and processed meats.

All dietary risks contribute to 47% of coronary heart disease, 26% of type 2 diabetes, 26% of bowel cancer, 24% of stroke, and 23% of oesophageal cancer.

All dietary risk factors contribute to about 6,900 deaths (9.0% of all female deaths). The ill health and death attributable to all dietary risks for females was 2.2 higher in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with the highest socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2021b).

For more information on the disease burden due to dietary risks, see Burden of disease.

Fruit and vegetables

The 2013 Australian Dietary Guidelines recommend for females to consume a minimum of 2 serves of fruit and 5 serves of vegetables each day, depending on age, to ensure good nutrition and health.

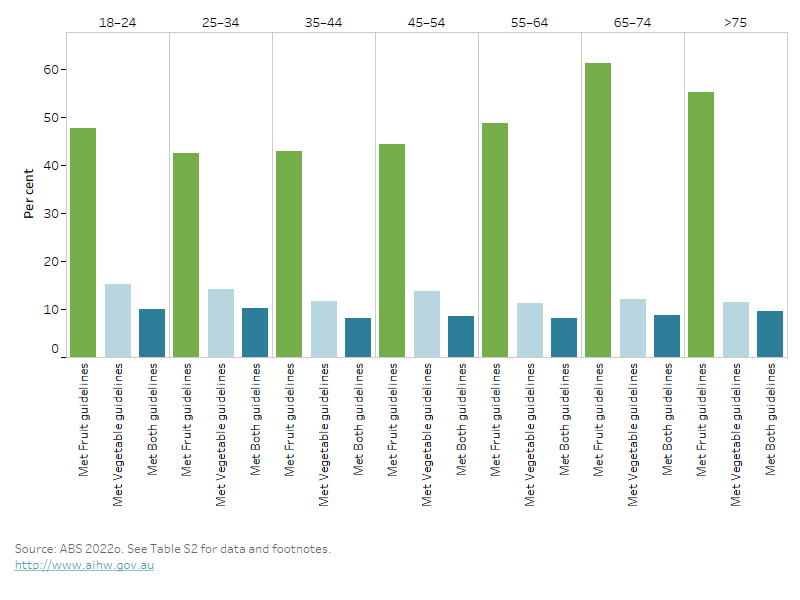

Among females:

- about half (48%) meet the guidelines for fruit intake

- 13% meet the vegetable intake guideline

- 9.0% meet the guideline for both fruit and vegetables (ABS 2022o) (Figure 17).

The proportion of females meeting both fruit and vegetable intake guidelines varies little by age group. About 10% of females aged between 25–34 meet the guidelines compared to 9.5% of those aged 75 and over years (Figure 18).

Figure 17: Fruit and vegetable consumption against the Australian Dietary Guidelines (percentage), females, 2020–21

Source: ABS 2022o. See Table S2 for data and footnotes.

Figure 18: Fruit and vegetable consumption against the Australian Dietary Guidelines (percentage) by age group, females, 2020–21

The bar chart shows that the percentage of people who meet the fruit and vegetable intake guideline varies little across age groups. Females generally eat more fruit than vegetables, and this is highest in the 65–74 age group where 61.4% meet the fruit intake guideline.

Whether females eat enough fruit and vegetables varies for some population groups. In 2017–18, after adjusting for age (ABS 2019b).

- females living in Inner regional areas are 1.5 times as likely than females in Major cities to be eating enough vegetables (14% and 9.5%, respectively)

- females living in the highest socioeconomic areas are 1.1 times as likely to be eating enough fruit as females in the lowest socioeconomic areas (58% and 52%, respectively)

- females living in the highest socioeconomic areas are 1.4 times as likely to be eating enough vegetables as females in the lowest socioeconomic areas (12% and 8.3%, respectively).

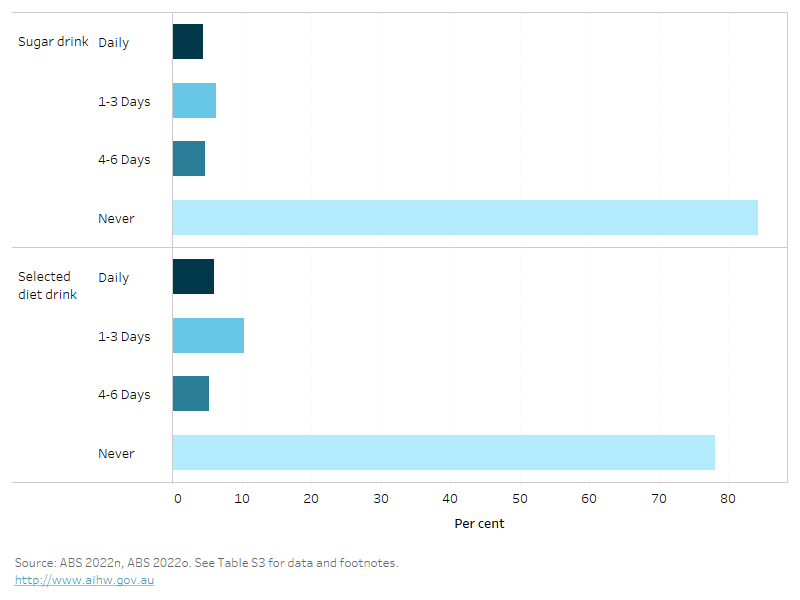

Sugar sweetened and selected diet drinks

Discretionary foods like sugar sweetened and selected diet drinks are not an essential part of a healthy diet and a limited intake of these is recommended in the Australian Dietary Guidelines. A diet high in sugar sweetened drinks is linked to type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease, and contributes to around 60 deaths among females (0.1% of all female deaths) (AIHW 2021b).

According to 2020–21 NHS data (Figure 19) (ABS 2022n):

- 4.5% of females drink sugar sweetened drinks daily, and 11% drink them less than daily (usually consume 1-6 days per week)

- 6.1% of females drink diet drinks daily, and 16% drink them less than daily (usually consume 1-6 days per week).

Figure 19: Consumption of sugar sweetened or selected diet drinks, by usual consumption per week, females, 2020–21

This horizontal bar chart shows the percentage of females who consume sugar sweetened or selected diet drinks by usual consumption per week. It shows that 6.1% of females drink diet drinks daily and 4.5% drink sugar sweetened drinks daily.

Notes:

- Sugar sweetened drinks includes soft drink, cordials, sports drinks or caffeinated energy drinks and may include soft drinks in ready to drink alcoholic beverages. Fruit juice, flavoured milk, ‘sugar free’ drinks or coffee/hot tea are excluded.

- Selected diet drinks include those that have artificial sweeteners added to them rather than sugar. Includes diet soft drink, cordials, sports drinks or caffeinated energy drinks. May include diet soft drinks in ready to drink alcoholic beverages. Excludes non-diet drinks, fruit juice, flavoured milk, water or flavoured water or coffee/tea flavoured with sugar replacements.

The percentage of females who consume sugar sweetened drinks daily varies by age group. More females aged 18–24 (8.4%) than males aged 65 and over (1.8%) drink sugar sweetened drinks daily (ABS 2022o).

Consumption also varies for some population groups. After adjusting for age (ABS 2019b):

- females living in Outer regional and remote areas are almost twice as likely to drink sugar sweetened drinks daily as females in Major cities (10% and 5.9%, respectively)

- females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas are 5 times as likely to drink sugar sweetened drinks daily as females in the highest socioeconomic areas (12% and 2.4%, respectively) (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Daily consumption of sugar sweetened drinks by socioeconomic group and remoteness areas (percentage), females, 2017–18

Note:

Sugar sweetened drinks includes soft drink, cordials, sports drinks or caffeinated energy drinks and may include soft drinks in ready to drink alcoholic beverages. Fruit juice, flavoured milk, ‘sugar free’ drinks or coffee/hot tea are excluded.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019b. See Table S3 for data and footnotes.

For more information on diet as a risk factor for poor health, see Diet.

Low levels of physical activity are a major risk factor for many chronic conditions. Being physically active improves mental and musculoskeletal health and reduces other risk factors such as overweight and obesity, high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol.

Physical inactivity is the 8th leading preventable cause of ill health and premature death among females, responsible for 2.5% of ill health and premature death in Australia in 2018 (AIHW 2021b). Physical inactivity is linked to type 2 diabetes, coronary health disease and stroke and 3 types of cancer.

Physical inactivity contributes to around 4,500 deaths (5.9% of all female deaths) (AIHW 2021c). The ill health and death attributable to physical inactivity for females is 1.9 times greater in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with the highest socioeconomic areas.

For more information on the disease burden due to insufficient physical activity, see Burden of disease.

Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines

Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines outline the minimum amount of physical activity required for health benefits (DoHAC 2019). These recommend that adults aged 18–64:

- accumulate 150 to 300 minutes (2.5 to 5 hours) of moderate intensity physical activity or 75 to 150 minutes (1.25 to 2.5 hours) of vigorous intensity physical activity or an equivalent combination of both moderate and vigorous activities, each week.

- do muscle-strengthening activities on at least 2 days each week.

For adults aged 65 and over, the Guidelines recommend at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on most, but preferably all days.

‘Sufficiently physically active’ refers to meeting the physical activity component of the Guidelines and is defined in this report as:

- completing 150 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week (where vigorous activity is multiplied by 2) and,

- being active on 5 or more days per week.

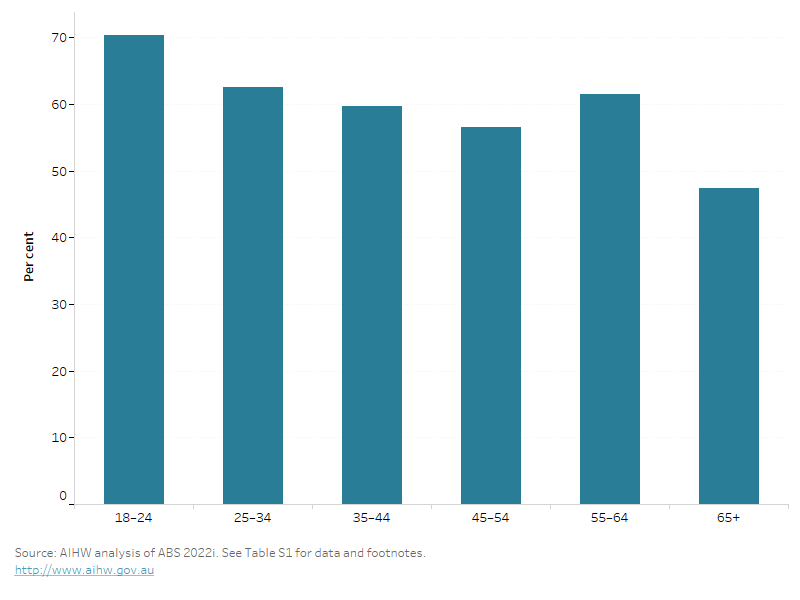

Among females, 59% do sufficient moderate and vigorous physical activity per week, and only 25% do sufficient strength or toning activities on 2 or more days per week, in 2020–21 (ABS 2022i).

Overall, only 21% of females meet both the physical activity and strength guidelines (Figure 21).

The proportion of females who are sufficiently physically active varies by age and for some population groups:

- Around 70% of females aged 18–24 are sufficiently physically active compared with around 47% aged 65 and over (Figure 22) (ABS 2022i).

- After adjusting for age, 49% of females living in the highest socioeconomic areas are sufficiently physically active compared with 34% in the lowest areas in 2017–18 (AIHW 2020b).

For more information, see Physical activity.

For information on physical activity for children and young people see Physical activity across the life stages report.

Figure 21: Physical activity guidelines compliance (percentage), females, 2020–21

Note: Includes workplace activity

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2022i. See Table S1 for data and footnotes.

Figure 22: Sufficient physical activity by age group, females, 2020–21

The bar chart shows the distribution of people who are sufficiently active across various age groups; physical activity generally decreases with age, with the most active age groups being 18–24 (70.3% met the physical activity guideline) and 55–64 (61.5% met the guideline).

Occupational exposures and hazards was the 14th leading risk factor for ill health and premature deaths for females (AIHW 2021b). It was estimated to contribute to 1.0% of ill health and premature death among females aged 15 and over in 2018 (AIHW 2021b). Occupational exposures and hazards is linked to a number of serious health conditions, including silicosis, asbestosis, COPD, falls, lung and ovarian cancers.

Occupational exposures and hazards contribute to around 170 deaths among females (0.2% of all female deaths) with the common causes of death being lung cancer, COPD, and acute myeloid leukaemia. (AIHW 2021b). The burden of Occupational exposures and hazards is almost 2 times higher for females in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with the highest socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2021b).

Deaths from traumatic injuries in the workplace are reported to SafeWork Australia. These are rare in females (6 of 169 traumatic injury fatalities in 2021). Over time, the rate of females killed at work has declined, from 0.5 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2007 to 0.1 per 100,000 workers in 2021(SWA 2021).

The most common types of workplace injuries among females in 2021 are (SWA 2021):

- Traumatic joint, ligament and muscle and/or tendon injury (41% of serious claims)

- Musculoskeletal and connective tissue diseases (18%)

- Mental health conditions (14%).

For more information see Safe Work Australia.

Violence is a broad term, often used to encompass a wide range of behaviours and definitions that vary according to different legislation and practices. Harm from violence can be wide-ranging, including physical, sexual and psychological, with serious and long-term impacts on individuals, families and communities (AIHW 2022s).

Family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) is a term used to capture forms of violence that occur within family relationships, and sexual violence that occurs in both family and non-family relationships. Broadly speaking, family relationships are between persons such as partners (or previous partners), parents, siblings, and other family members or kinship relationships.

Experiences of violence since the age of 15

Almost 2 in 5 females (39%) have experienced physical and/or sexual violence since the age of 15. One in 3 (31%) experienced at least one incident of physical violence, and 1 in 5 (22%) experienced at least one incident of sexual violence (ABS 2023d). Females experience more violence, whether physical or sexual, from a known person (35%) than from a stranger (11%).

Experiences of violence, and emotional abuse in the last 12 months

In the last 12 months, 4.2% of females have experienced physical and/or sexual violence (ABS 2023d). There was also 3.9% of females who experienced emotional abuse in the last 12 months (ABS 2023e).

Based on 2016 data, the highest rates of physical and/or sexual violence was reported as the highest among females aged 18–24 (12%) and the lowest among those aged 65 and over (1.2%) (ABS 2017a). The experience of physical and/or sexual violence has also previously been reported as being 1.4 times greater in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with the highest socioeconomic areas (ABS 2017a).

Intimate partner violence

Violence between partners is sometimes referred to as partner violence, or intimate partner violence, and can cover cohabiting partners and boyfriend/girlfriend/dates (AIHW 2022s).

Intimate partner violence is responsible for 1.4% of ill health and deaths in females (AIHW 2021b). Among females aged 15 and over, intimate partner violence contributes to 46% of homicide & violence ill health, and 19% of suicide & self-inflicted injuries. In addition, it contributes 17% of early pregnancy loss, 15% of depressive disorders, 12% of anxiety disorders and 4% of alcohol use disorders (AIHW 2021c).

Intimate partner violence contributed to about 230 deaths among females (0.3% of all female deaths) in 2018. The burden of intimate partner violence is 2.5 times greater in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with the highest socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2021b).

Since the age of 15, experiences of intimate partner violence, either sexual or physical, was reported by 23% of females (ABS 2023d).

In the previous 12 months, 1.5% of females indicated they had experienced intimate partner violence (ABS 2023e).

Almost 23% of females have experienced emotional abuse since the age of 15 from a cohabiting partner (ABS 2023d). Based on 2016 data, females reported that being shouted at, yelled at or verbally abused to intimidate them was the most common abusive behaviour they experienced from a current (58%) or previous (63%) partner (ABS 2017b).

For information on family, domestic and sexual violence see Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia.

ABS (2017a) Personal Safety, Australia 2016, [Table 6.3], abs.gov.au, accessed 29 September 2022.

ABS (2017b) Personal Safety, Australia 2016, [Table 28.3], abs.gov.au, accessed 29 September 2022.

ABS (2018a) Overweight and obesity, abs.gov.au, accessed 6 December 2022.

ABS (2019a) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, detailed microdata, DataLab. Findings based on AIHW analysis of ABS microdata, ABS DataLab, Canberra, accessed 9 December 2022.

ABS (2019b) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2018–19, AIHW analysis of fruit and vegetable consumption, ABS DataLab, Canberra, accessed 9 December 2022.

ABS (2022f) Insights into Australian smokers, 2021-22, [Table 2.3 Current smoker status by age and sex], accessed 23 February 2023.

ABS (2022i) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2020-21, AIHW analysis of Physical activity by age, ABS DataLab, Canberra, accessed 14 June 2022.

ABS (2022l) NHS 2020-21, Alcohol consumption, [Table 7.3, Alcohol by age and sex], abs.gov.au, accessed 29 September 2022.

ABS (2022m) NHS 2020-21, Smoking, [Table 6.3: Smoking], abs.gov.au, accessed 29 September 2022.

ABS (2022n) NHS, Dietary behaviour, [Table 9.11: Consumption of fruit, vegetables and sugar sweetened diet drinks, 2020–21], abs.gov.au, accessed 29 September 2022.

ABS (2022o) NHS, Health Conditions Prevalence, [Table 9.11: Consumption of fruit, vegetables and sugar sweetened diet drinks, 2020–21], abs.gov.au, accessed 29 September 2022.

ABS (2023d) Personal Safety, Australia 2021-22, [Table 1.3], abs.gov.au, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2023e) Personal Safety, Australia 2021-22, [Table 2.3], abs.gov.au, accessed 17 March 2023.

AIHW (2020a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, AIHW website, accessed 7 December 2022.

AIHW (2020b) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019 [Table s4.4], AIHW website, accessed 16 May 2022.

AIHW (2020c) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, [Data tables: National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019 – 4, Table 4.15, Illicit use of drugs supplementary tables], AIHW website, accessed 16 May 2022.

AIHW (2021b) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW website, accessed 17 October 2022.

AIHW (2021c) Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW website, accessed 7 October 2022.

AIHW (2022a) Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, [Table S2.2: Exceedance of lifetime alcohol risk guidelines], AIHW website, accessed 27 February 2023.

AIHW (2022k) Australian Burden of Disease Study, AIHW website, accessed 7 October 2022.

AIHW (2022s) Family, domestic and sexual violence: National data landscape 2022, AIHW website, accessed 8 February 2023.

AIHW (2022y) Procedures data cubes, 2020-21, AIHW website, accessed 22 November 2022.

AIHW (2023a) AIHW analysis of Australian Burden of Disease Study, 2018, AIHW, accessed 24 May 2023.

AIHW (2023c) Overweight and obesity, AIHW website, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023d) Overweight and obesity, [Table S5], AIHW website, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023e) Overweight and obesity, [Table S2], AIHW website, accessed 19 May 2023.

DoHAC (Department of Health and Aged Care) (2019) Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians, health.gov.au, accessed 23 October 2022.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) (2020) Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol, nhmrc.gov.au, accessed 22 February 2023.

SWA (Safe Work Australia) (2021) Work-related traumatic injury fatalities Australia 2021, safeworkaustralia.gov.au, accessed 8 June 2022.