Availability of perinatal data

To date, there is no national data about perinatal mental health screening, service use or outcomes. Data about the mental health of parents in the perinatal period are collected by a range of health services, Australian Government and state and territory government agencies, and non-government organisations, mostly as a by-product of delivering maternity services. The range of settings has implications for the ease with which comparable data can be extracted and collated into a national data collection.

A number of existing data collections currently offer some insight into perinatal mental health, including the:

- National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC)

- National Maternal Mortality Data Collection (NMMDC)

- Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).

In addition, large-scale longitudinal studies also provide insight, including the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health survey.

Data relating to the mental health of mothers are also routinely collected in national hospital, hospital emergency department, and pharmaceutical data collections, however data linkage would be required to identify women in the antenatal and postnatal period.

National Perinatal Data Collection

The NPDC is Australia’s authoritative source of data about pregnancy and childbirth. Each state and territory health authority maintains its own perinatal data collection about births in its jurisdiction and provides an annual standard extract of the data to the AIHW for national collation. Work to include antenatal mental health data in the NPDC commenced in 2010, and in July 2020, three antenatal mental health data items and one family violence screening data item were introduced as part of the voluntary Perinatal NBEDS:

- Antenatal mental health risk screening status (Yes, Not offered, Declined)

- Indication of possible symptoms of depression at an antenatal care visit (total EPDS score)

- Presence or history of mental health condition indicator (Yes, No)

- Family violence screening status (Yes, Not offered, Declined).

The Perinatal NBEDS is not mandated for national collection but there is a commitment to provide data nationally on a best endeavours basis. State and territory health authorities are at different stages in implementing the data items for a variety of reasons. Four state and territory health authorities supplied at least one of the four data items for both the 2020 and 2021 birth cohorts (Table 1). For further information, see Data opportunities.

National Maternal Mortality Data Collection

The National Maternal Mortality Data Collection (NMMDC) is a national data collection of maternal deaths (up to and including 42 days postpartum, irrespective of the duration or outcome of the pregnancy). The NMMDC includes data on if the death was caused by suicide, if mental health screening was offered, complications in the pregnancy and up to 42 days postpartum (including Mental health illness) and pre-existing conditions (including Mental health illness).

Medicare Benefits Schedule

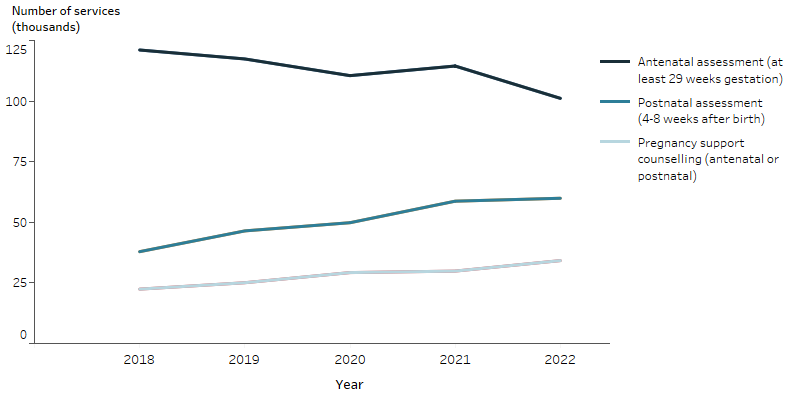

The MBS data collection contains information on services that qualify for a benefit or subsidy and for which a claim has been processed. It includes two antenatal and three postnatal obstetric items that require the claiming GP or obstetrician to offer a ‘mental health assessment’ to the patient. Between 2018 and 2022, the number of these antenatal services claimed per year decreased, from around 121,000 services in 2018 to around 101,000 services in 2022. Use of the postnatal items has increased steadily per year, from around 37,900 services claimed in 2018 to around 59,900 services in 2022 (Figure 3).

Medicare subsidises antenatal and postnatal services delivered in the community and to admitted private hospital patients by GPs, midwives, specialists and some allied health workers. This does not include services provided to public hospital patients, including antenatal clinics run by public hospitals. It is currently unknown what proportion of antenatal and postnatal services this represents.

The MBS also includes items for non-directive Pregnancy Support Counselling provided by GPs, other eligible medical practitioners (not including specialists or consultant physicians), psychologists, social workers and mental health nurses to patients who are pregnant or 1 year postpartum. Pregnancy support counselling does not need to relate to a patient’s mental health and can be used to discuss any pregnancy related concerns such as parenting, health, relationship and financial concerns. Use of these services has steadily increased, from around 22,500 services claimed in 2018 to 34,200 services in 2022 (Figure 3). These services were provided to patients out of hospital, and the bulk were provided by GPs (96% of services in 2022).

Figure 3: Number of Medicare-subsidised perinatal mental health-related services, by service type, 2018 to 2022

In 2018 there were 121,078 MBS funded services for antenatal assessment (at least 29 weeks gestation).

In 2019 there were 117,385 MBS funded services for antenatal assessment (at least 29 weeks gestation).

In 2020 there were 110,502 MBS funded services for antenatal assessment (at least 29 weeks gestation).

In 2021 there were 114,467 MBS funded services for antenatal assessment (at least 29 weeks gestation).

In 2022 there were 101,136 MBS funded services for antenatal assessment (at least 29 weeks gestation).

In 2018 there were 37,882 MBS funded services for postnatal assessment (4-8 weeks after birth).

In 2019 there were 46,451 MBS funded services for postnatal assessment (4-8 weeks after birth).

In 2020 there were 49,829 MBS funded services for postnatal assessment (4-8 weeks after birth).

In 2021 there were 58,712 MBS funded services for postnatal assessment (4-8 weeks after birth).

In 2022 there were 59,917 MBS funded services for postnatal assessment (4-8 weeks after birth).

In 2018 there were 22,429 MBS funded services for pregnancy support counselling (antenatal or postnatal).

In 2019 there were 25,069 MBS funded services for pregnancy support counselling (antenatal or postnatal).

In 2020 there were 29,256 MBS funded services for pregnancy support counselling (antenatal or postnatal).

In 2021 there were 29,866 MBS funded services for pregnancy support counselling (antenatal or postnatal).

In 2022 there were 34,197 MBS funded services for pregnancy support counselling (antenatal or postnatal).

Note: Results are by date of processing. Antenatal items include items 16590 and 16591. Postnatal items include items 16407, 91851 and 91856. Pregnancy support counselling items include 4001, 792, 81000, 81005, 81010, 93026, 93029, 92136, 92137, 92138 and 92139.

Although the antenatal items have existed since 2004, these items were updated in November 2017 to require the medical practitioner to offer a mental health assessment (previously it was at the discretion of the medical practitioner).The postnatal items requiring an assessment to be offered were introduced from November 2017.

Source: AIHW analysis of Medicare Benefits Schedule item reports. Sourced on 23 October 2023.

It should be noted that the MBS claims data does not include information about if or how the woman was screened (that is, the tools used) or the outcome of the mental health screening – the selected antenatal and postnatal items only tell us that the woman has been ‘offered’ a mental health assessment. In addition, this is likely to be underestimated, as GPs and obstetricians might provide similar services under different ‘general’ MBS items (for example, item 23), or a mental health-specific item that is not specific to women in the antenatal or postnatal period.

As such, while the MBS claims data can give an indication of the number of women being offered perinatal mental health screening in out of hospital settings, or to private admitted patients of public and private hospitals, its use for monitoring perinatal mental health is limited without linkage to another data source that identifies women in the antenatal and postnatal period.

Surveys and longitudinal studies

There are several large scale and ongoing surveys and longitudinal studies in Australia that provide insight into perinatal mental health screening and outcomes (Table 2), including:

Table 2: Overview of Australian surveys and longitudinal studies related to perinatal mental health

Mothers

| Study | Perinatal mental health scope | In scope cohort | Representativeness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (Loxton et al. 2021) | Mothers were asked: ‘For your most recent pregnancy, were you asked any questions by a midwife, GP, child health nurse or other professional about your emotional wellbeing? (e.g., given a questionnaire to complete)’. | 1973–78 cohort: Across the 2009 to 2018 surveys (aged 31 to 42), 1,180 women reported giving birth in the three years before the survey. 1989–95 cohort: Across the 2017 and 2019 surveys (aged 22 to 29), 1,083 women reported giving birth in the three years before the survey. Perinatal mental health related questions were not included in the 2020 survey but may be included in future years. | 1973–78 cohort: Randomly sampled from the Medicare database in 1996. Women from rural and remote areas were oversampled to support analysis of this group. 1989–95 cohort: Recruited by traditional methods (referral, print and commercial media) and social media/marketing campaigns in 2013. Women with tertiary education were overrepresented, and women from non-English speaking backgrounds were underrepresented. |

| Australian Genetics of Depression study (Kiewa et al. 2022) | Women with self-reported perinatal depression were asked about symptom onset and prior depression history. | 2,261 women with perinatal depression with a prior depression history. 878 women with perinatal depression with no prior depression history. | Women with major depression were recruited during 2016-2018. The Australian Genetics of Depression Study cohort is mostly young and well-educated and may not generalise to the entire population. |

| The Mothers’ and Young People’s Study (Brown et al. 2021) | Mothers and offspring are given a range of mental health and behavioural measures. | 2003-2005: Over 1,500 first-time mothers and their first-born children from pregnancy to age 18. | Women were recruited from six Melbourne metropolitan hospitals between 2003-2005. Younger women (aged 18–24 years) and women born overseas in non-English speaking countries were underrepresented. |

Fathers

| Study | Perinatal mental health scope | In scope cohort | Representativeness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ten to men: Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health (AIFS 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d) | Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (depressive symptoms, no assessment of anxiety or stress). Age of child is not recorded, and no questions specific to mental health during the perinatal period. | Wave 1 (2013/14): 7,458 fathers to children under 18. Wave 2 (2015/16): 205 new fathers since Wave 1 (5,648 fathers to children under 18). Wave 3 (2020/21): 3,403 fathers to children under 18. | Low response rate (35% of eligible males). Sampling not conducted in remote and very remote areas while inner and outer remote areas were oversampled. |

| Men and Parenting Pathways (MAPP) Study (Macdonald et al. 2021) | 21-item Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales, as well as measures of anger, irritability, parenting, traits, substance use and social support. | Wave 1: 241 fathers to 421 children. Waves 2 and 3: 67 new fathers and 156 new births. 44 new fathers identified after wave 3 completion. Waves 4 and 5: in progress. | Small sample size (608 men aged 28-32 when recruited between 2015 and 2017), although fairly representative. |

Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) (2021a) Ten to Men: the Australian longitudinal study on male health – data user guide, AIFS, accessed 26 September 2023.

AIFS (2021b) Ten to Men: the Australian longitudinal study on male health – wave 1 data book – Adults (18–55 years), AIFS, accessed 26 September 2023.

AIFS (2021c) Ten to Men: the Australian longitudinal study on male health – wave 2 data book – Adults (18–55 years), AIFS, accessed 26 September 2023.

AIFS (2021d) Ten to Men: the Australian longitudinal study on male health – wave 3 data book, AIFS, accessed 26 September 2023.

Brown SJ, Gartland D, Woolhouse H, Giallo R, McDonald E, Seymour M, Conway L, FitzPatrick KM, Cook F, Papadopoullos S, MacArthur C, Hegarty K, Herrman H, Nicholson JM, Hiscock H and Mensah F (2021) ‘The maternal health study: study design update for a prospective cohort of first-time mothers and their firstborn children from birth to age ten’, Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 00:1–14, doi:10.1111/ppe.12757.

Kiewa J, Meltzer-Brody S, Milgrom J, Bennett E, Mackle T, Guintivano J,Hickie IB, Colodro-Conde L, Medland SE, Martin N, Wray N and Byrne E (2022) ‘Lifetime prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression in a case-cohort study of depression’, BMJ Open, 12:e059300, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059300.

Loxton D, Byles J, Tooth L, Barnes I, Byrnes E, Cavenagh D, Chung H-F, Egan N, Forder P, Harris M, Hockey R, Moss K, Townsend N and Mishra G (2021) Reproductive health: contraception, conception, and change of life – findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health, accessed 26 September 2023.

Macdonald JA, Francis LM, Skouteris H, Youssef GJ, Graeme LG, Williams J, Fletcher RJ, Knight T, Milgrom J, Di Manno L, Olsson CA and Greenwood CJ (2021) ‘Cohort profile: the Men and Parenting Pathways (MAPP) Study: a longitudinal Australian cohort study of men’s mental health and well-being at the normative age for first-time fatherhood’, BMJ Open, 11:e047909. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-047909.