Government sources: Australian Government spending

On this page:

Australian Government spending

In 2020–21, Australian Government spending was $94.4 billion, representing a $5.8 billion real increase (6.5%) from 2019–20 (Table 10). This was more than double the average annual real growth in the decade to 2020–21 (3.2%) and also higher than 2019–20 (5.1%).

The growth of Australian Government spending between 2019–20 and 2020–21 was due mainly to increases in direct Australian Government spending (8.5%) and grants to states and territories (5.4%), while the health spending associated with the health insurance premium rebate increased by 1% and DVA spending decreased by 6.1%. Among the direct Australian Government spending, the biggest increases were in public health (including spending on masks and personal protective equipment and COVID–19 vaccines) and referred medical services (including COVID–19 testing, diagnostic imaging, specialist services, among others).

Spending relative to government expenses and taxation revenue

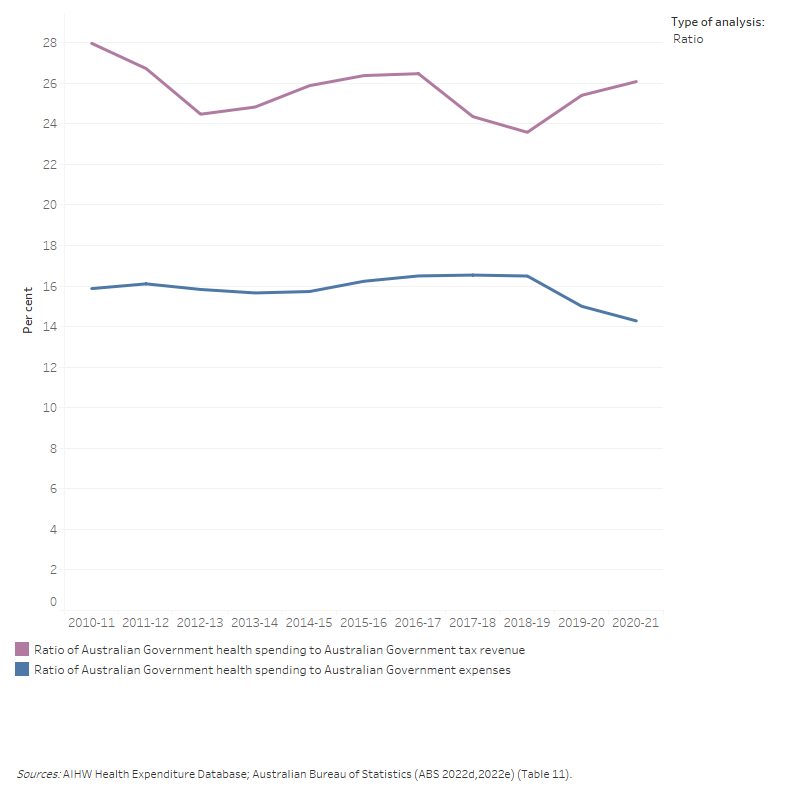

During 2020–21, the $94.4 billion health spending by the Australian Government was 14.3% of its expenses (Figure 9). Decreases in the ratio over the past 2 years have left the ratio well below pre-pandemic levels, which indicates that growth in health spending has been slower than other areas of Australian Government spending (Table 11). More details on the Australian Government’s Economic Response to COVID-19 can be found on the Australian Government Department of Treasury website.

In 2020–21, the Australian Government's health spending represented 26.1% of its tax revenue, approximately 0.7 percentage points higher than in 2019–20 (Figure 9). This is attributed to Australian Government nominal health spending growing faster than government tax revenue (9.1% compared with 6.3% over 2020–21, in nominal terms) (Table 11). Despite this growth in the ratio over the past 2 years, the ratio remains below previous peaks (during the Global Financial Crisis period between 2009–10 and 2011–12).

Figure 9: Ratios of Australian Government health spending to Australian Government tax revenue and government expenses, current prices, 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows the dollar amounts of the Australian Government tax revenue and health spending with an additional line showing the ratio of the Australian Government health spending to tax revenue as a percentage. Australian government health spending increased from $56.7 billion in 2010–11to $94.4 billion in 2020–21. Australian Government tax revenue was higher than health spending for all years. Tax revenue increased from $202.7 billion in 2010–11 to $361.9 billion in 2020–21. The highest ratio of 28.0 per cent was in 2010–11 and the lowest one was 23.6 per cent in 2018–19.

Spending programs

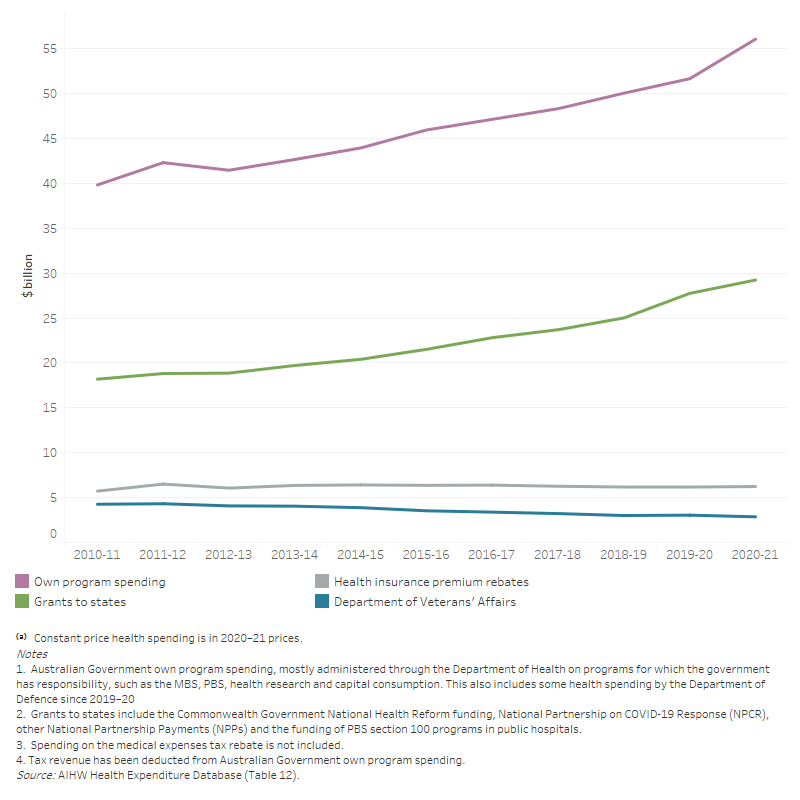

Australian Government spending in 2020–21 (Figure 10) comprised:

- direct Australian Government spending ($56.1 billion, or 59.4%), mostly administered through the Department of Health and Aged Care (DoHAC) on programs for which the government has responsibility, such as the MBS, PBS and health research. This also includes some health spending by the Department of Defence ($576 million).

- grants to states and territories ($29.2 billion, or 31.0%), including National Health Reform funding (mainly comprising public hospital funding), National Partnership on COVID–19 Response (NPCR), other National Partnership Payments (NPPs) and the PBS Section 100 funding in public hospitals

- rebates and subsidies for privately insured people under the national Private Health Insurance Act 2007 ($6.2 billion, or 6.6%)

- DVA funding for goods and services provided to eligible veterans and their dependants ($2.9 billion, or 3.0%).

The 6.5% increase in Australian Government spending between 2019–20 and 2020–21 can be attributed to increases in spending through specific DoHAC programs ($4.4 billion increase) and funding to states and territories through grants ($1.5 billion increase). The main driver of this increase was COVID–19 related health spending funded by the Australian Government such as spending on masks and personal protective equipment, COVID–19 vaccines and tests.

Figure 10: Australian Government total health spending by program, constant prices(a), 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that from 2010–11to 2020–21 the Australian Government spent the most to least on own program spending, grants to states, health insurance premium rebates and Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Over the 10-year period, there was an overall increase in health spending by the Australian Government for each program excluding on Department of Veterans’ Affairs. In 2020–21, The Australian Government spent $56.1 billion on own program spending, $29.2 billion on grants to states, $6.2 billion on health insurance premium rebates and $2.9 billion on Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

COVID–19 related health spending funded by the Australian Government in 2020–21

The pandemic impacted health spending in many ways, often through increasing the cost and complexity of service delivery in ways that are difficult to quantify. There were, however, some large COVID–19–specific response programs, such as the National Partnership on COVID–19 Response (NPCR) and spending on COVID–19–related programs by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (DoHAC, including Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS)).

During 2020–21, there was an estimated $10.2 billion spent through these programs ($4.0 billion on the NPCR and $6.2 billion on the DoHAC programs) in current prices.

Spending on the National Partnership on COVID–19 Response

During 2020–21, the Australian Government spending through the NPCR was $4.0 billion. This comprised:

- hospital services payments ($1.3 billion, or 33.0%)

- state public health payments ($2.3 billion, or 58.1%)

- private hospital financial viability payment ($0.4 billion, or 8.9%).

Australian Government spending through DoHAC programs

In 2020–21, DoHAC spending on specifically identifiable COVID–19 programs was estimated to be $6.2 billion. The distribution of the spending in 2020–21 included:

- 41.7% ($2.6 billion) on COVID–19–related medical services (mainly related to COVID–19 vaccine suitability assessment services, as well as other referred and unreferred medical services through MBS-funded telehealth)

- 20% ($1.2 billion) on COVID–19 medical goods and equipment (mainly related to distribution of masks and personal protective equipment products for the national medical stockpile)

- 17.3% ($1.1 billion) on Other COVID–19–related health spending (largely related to mental health programs, public health mainly related to primary care respiratory clinics and a national communication campaign)

- 14.7% ($0.9 billion) on COVID–19 vaccinations (mainly provided access to, and delivery of, COVID–19 vaccines as part of the national rollout)

- 4% ($0.2 billion) on COVID–19 testing (mainly through MBS-funded COVID–19 testing)

- 2.3% ($0.1 billion) on COVID–19–related investments.

Note that COVID–19 related spending for residential aged care is outside the scope of this report. This also does not include COVID–19 related spending by other Australian Government agencies, which might fall into a broader scheme economic response to COVID–19.

MBS, PBS and RPBS government benefits paid in 2020–21

In 2020–21, the Australian Government funded $27.5 billion as government benefits paid for MBS services.

During the same year, the Australian Government funded $13.4 billion as subsidies for PBS and $0.3 billion for RPBS pharmaceuticals.

Area of spending

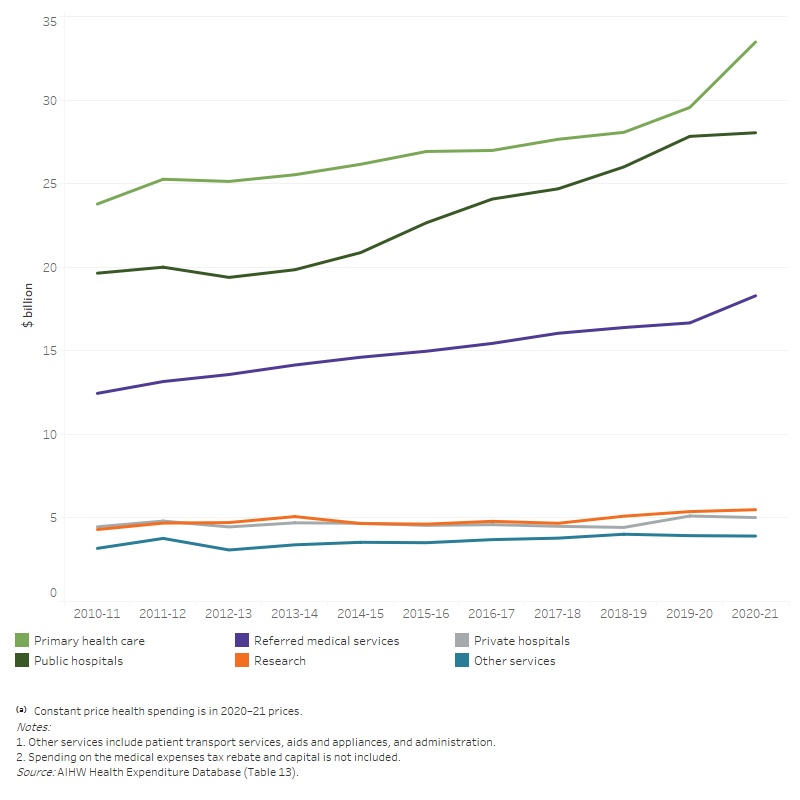

During 2020–21, more than one-third (35.5%) of Australian Government health spending was for primary health care ($33.5 billion) (Figure 11). Of this:

- unreferred medical services (mainly visits to a general practitioner) was $11.2 billion

- pharmaceuticals subsidised through the PBS (not including Section 100 drugs and other drugs that could be allocated to the areas of public hospital services and private hospitals) contributed $11.0 billion

- public health was $4.8 billion

- spending on other health practitioners was $2.8 billion (Table A6).

Figure 11: Australian Government health spending, by area of spending, constant prices(a), 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that health insurance premium rebates increased overall from 2010–11 to 2020–21. Health insurance premium rebates was highest in 2011–12 ($6.5 billion) and lowest in 2010–11($5.7 billion).

Spending on public hospitals was the next largest area of Australian Government health spending (between $28.1 billion and $29.7 billion depending on how some MBS benefits for services provided in public hospitals are treated), followed by referred medical services ($18.3 billion or $15.0 billion also depending on how some MBS spending is treated).

The estimated spending on public hospitals and referred medical services by the Australian Government is represented as a range here to reflect additional components of MBS spending that have not historically been treated as public hospital spending in the national health accounts methodology but that are believed to be related to services provided in public hospitals.

MBS funding by the Australian Government in public and private hospitals

The lower bound of $28.1 billion of the Australian Government spending on public hospital services includes spending by the Department of Veteran’s Affairs (DVA), National Health Reform funding, PBS section 100 programs (Highly Specialised Drugs, PBS Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy program, Chemotherapy Pharmaceutical Access Program (CPAP) and the Special Authority Program (trastuzumab - Herceptin), Botulinum Toxin Program, and Human Growth Hormone program) delivered through hospitals, a small grouping of other National Partnership Payments, an allocation of the private health insurance premium rebates, some specific programs administered by the Department of Health and Aged Care and Department of Defence and capital consumption allocated to public hospitals. More details can be found in Table A11.

This amount currently does not include:

(i) Government benefits paid for in-hospital MBS, mostly for private patients in public and private hospitals. This includes both inpatients and outpatients (at public hospitals’ outpatient clinics). The majority of these components are currently allocated to Referred medical services. This is primarily because limitations in the MBS data mean public hospital spending cannot be directly derived, including:

(i.1) Only MBS payments for medical services provided to admitted patients are flagged as ‘in hospital’. Outpatient and non-medical services are not recorded as hospital services.

(i.2) MBS ‘in-hospital’ services cannot be differentiated by services provided to private patients in a private hospital versus services provided to private patients in a public hospital.

(i.3) In addition, MBS payments are generally made to individual patients and individual practitioners, rather than directly to hospitals. There are, however, arrangements in place, particularly between practitioners and hospitals, that can mean that part or all of the MBS benefits are passed on to the hospital in lieu of payments from patients or fees for private practice arrangements for practitioners in public hospitals. A lack of detail regarding exactly who ultimately receives the MBS benefits and these payments are treated in data provided by both the Australian Government and the states and territories has meant that there is currently no consensus as to how best to treat this revenue in the ANHA.

While these limitations currently prevent the full incorporation of these MBS components into the area of public and private hospital spending, the AIHW has worked and will continue to work with the HEAC to develop a method for quantifying the amount of spending involved for the MBS components and to better understand the likely flow-on impact for other spending categories such as referred medical services and benefit-paid pharmaceuticals.

The estimated quantities of these components are provided below for both public and private hospitals. This does not include an estimate of the non-medical components for the MBS for private hospitals as there is no data currently available to quantify this.

In terms of the flow-on impacts, the full inclusion of this new way of categorising this spending into the ANHA would result in reductions to the estimates for referred medical services (as spending is reallocated to hospitals) in addition to increasing the Australian Government contributions for both public and private hospitals. The full inclusion would also be likely to result in reductions to public hospital spending estimates for Individuals and potentially State and territories, however the full effects require further work with HEAC to determine. The greatest impact is likely to be on the estimates for spending by Individuals on public hospital services, however, it is difficult to be certain of this given limitation in the available data.

Private hospitals spending would not be associated with the same degree of flow-on issues because the current estimation methods already exclude these amounts.

| Current figure | MBS for admitted patients | MBS for non-admitted patients | Total estimates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public hospitals | 28,052 | 683 | 915 | 29,650 |

| Private hospitals | 5,023 | 2,649 | 7,672 | |

| Total hospitals | 33,075 | 3,332 | 915 | 37,322 |

The AIHW is continuing to work with data providers and HEAC to resolve outstanding issues and fully incorporate these new estimates into the ANHA.

Using the current estimates, the rise in total Australian Government spending between 2019–20 and 2020–21 was mostly due to an increase of $3.9 billion on primary health care (mostly public health by $2.9 billion, including spending on masks, personal protective equipment and COVID–19 vaccines), $1.6 billion on referred medical services (including spending on COVID–19 testings, diagnostic imaging, specialist services, among others), $0.2 billion on public hospitals, and $0.1 billion on research (Figure 11).

Over the decade since 2010–11, referred medical services had the highest average annual growth rate by the Australian Government (3.9% per year), followed by public hospital services (3.6% per year) and primary health care (3.5% per year) (Figure 11). Note that growth calculations for Australian Government public hospital funding do not include additional components of MBS spending as stated above.

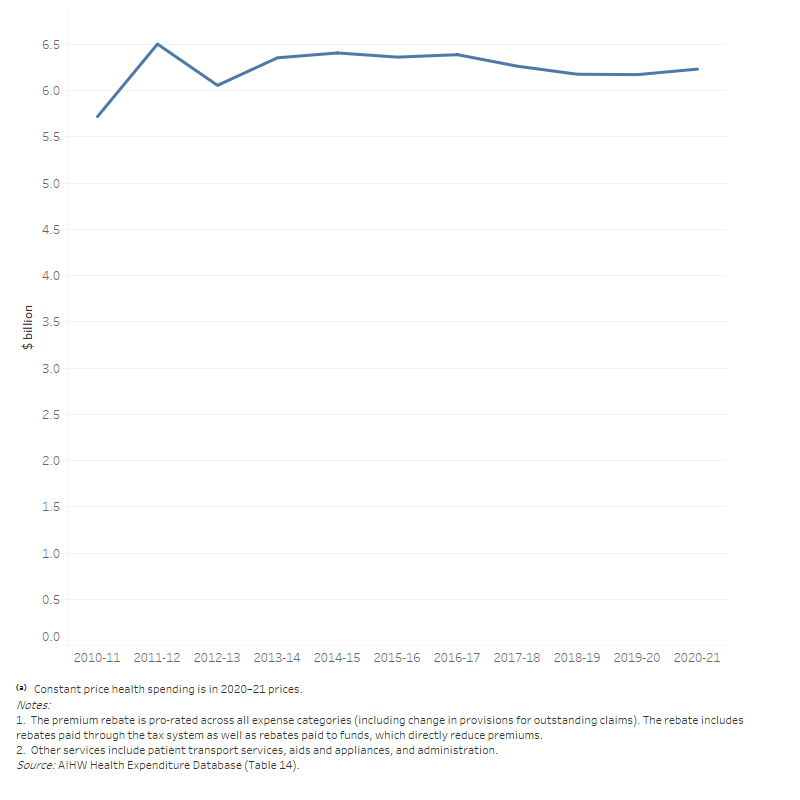

Private health insurance premium rebates

In 2020–21, the rebate for private health insurance premiums paid by the Australian Government was $6.2 billion, a real increase of $60 million from 2019–20 (Figure 12). The rebate amount presented here is an estimate of the rebate paid out as benefits (to estimate health spending). This is done to exclude spending on non-health related items such as health insurance advertising. It is therefore smaller than the total rebate paid to individuals to reduce premiums, which are reported elsewhere (such as in DoHAC and ATO annual reports). More details on the estimation can be found in the Australian National Health Account: concepts, methodology and data sources.

Figure 12: Health insurance premium rebates as health spending, constant prices(a), 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that health insurance premium rebates increased overall from 2010–11 to 2020–21. Health insurance premium rebates was highest in 2011–12 ($6.5 billion) and lowest in 2010–11($5.7 billion).

Department of Veterans’ Affairs spending

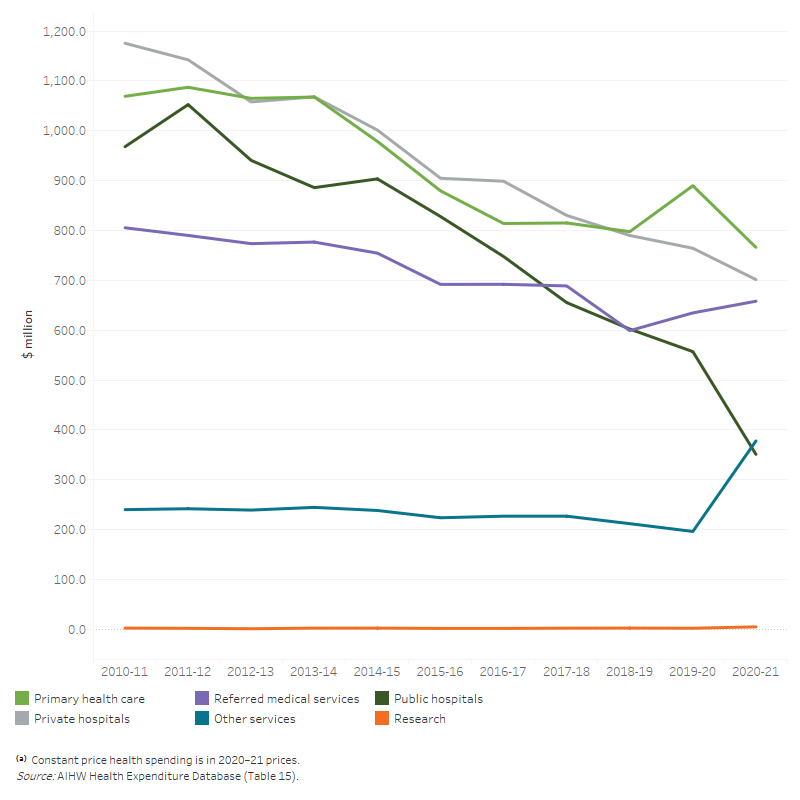

In 2020–21, the DVA spent $2.9 billion on health, mostly on hospitals ($1.1 billion), primary health care ($0.8 billion) and referred medical services ($0.7 billion). Total DVA spending decreased by 6.1% in 2020–21 (Figure 13a). Note that DVA changed their reporting system of health expenditure in 2020–21 which has some impacts on the time series of health spending in this report. Therefore, caution should be exercised when comparing results between years.

DVA spending on hospitals declined over the decade to 2020–21, with public hospitals decreasing by an average of 9.6% per year and private hospitals by 5.0% in real terms. Once again, note that the change of DVA reporting system affected the growth rates over the years. DVA spending on primary health care also decreased in real terms by a yearly average of 3.3%, accompanied by an average decrease in spending on referred medical services by 2.0%. During this period, Other services (including Patient transport services, Aids and appliances, and Administration) increased by 4.6%.

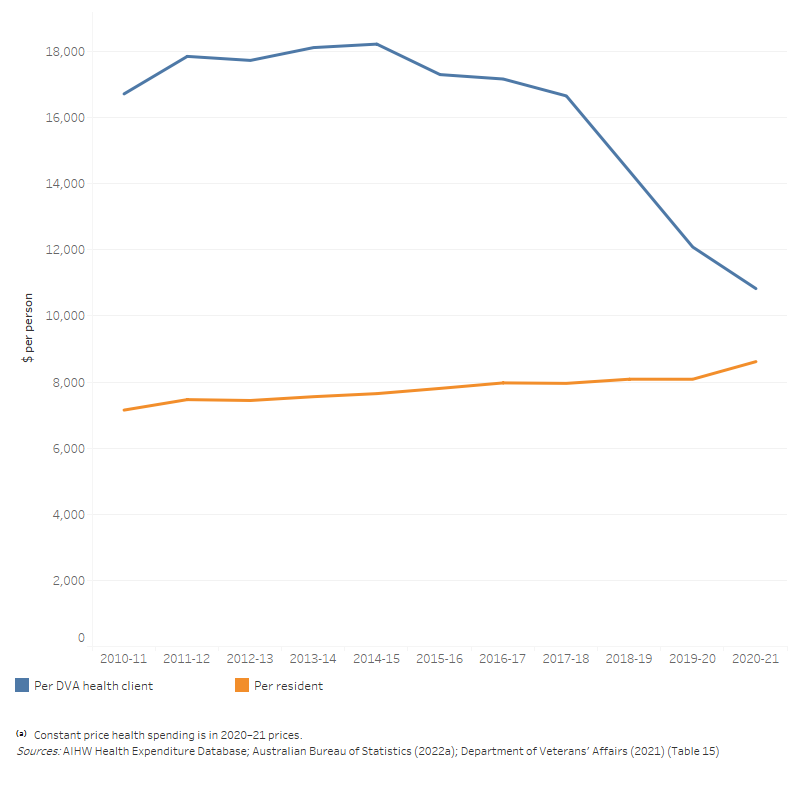

Based on the number of people in the DVA treatment population (which includes all DVA Orange, Gold and White cardholders), DVA spent $10,827 on health per member of the treatment population in 2020–21 which is 25.6% higher than the health spending per person in the total Australian population ($8,617). This average health spending per member of the DVA treatment population peaked in 2014–15 and decreased over the period 2015–16 to 2020–21 (Figure 13b). This recent downward trend in the health spending per member of the DVA treatment population is due to the decline in Veteran Gold Card Holders and increase in Veteran White Card Holders. DVA will pay for the hospital treatment costs for Veteran White Card holders for accepted conditions or conditions under non-liability health care whereas all hospital services that meet the clinical needs of Veteran Gold Card holders are paid by DVA.

Figure 13a: Department of Veterans’ Affairs health spending by area of spending, constant prices(a), 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that Department of Veterans’ Affairs spent the most on primary health care and least on research. In 2020–21, $351 million was spent on public hospitals, $702 million on private hospitals, $766 million on primary health care, $658 million on referred medical services, and $378 million on other services.

Figure 13b: Average health spending per client of the DVA treatment population and per person in the Australian resident population, constant prices(a), 2010–11 to 2020–21 ($)

Average health spending per client of DVA treatment population increased from $16,717 in 2010–11 to $18,223 in 2014–15, and then decreased to $10,827 in 2020–21. Health spending per member of DVA treatment population is often higher than the health spending per person in the total Australian population during the 10-year period.

Department of Defence health spending

In 2020–21, the Department of Defence (Joint Health Command) spent $576 million on health. This was an increase of 10% ($52.5 million) from 2019–20 in real terms. In 2020–21, the biggest area of spending was other health practitioners ($156 million), followed by referred medical services ($133 million), unreferred medical services ($90 million), private hospitals ($77 million), dental services ($51 million) and administration ($44 million).

The amounts shown represent actual health expenditure by the Department of Defence for its ADF and APS employees that could be categorised as per AIHW’s area of expenditure classification, including direct spending on health care to members, direct costs of pharmaceuticals purchased by the Department and costs for administration, including the Defence electronic health record.

Note that it is not possible to reconcile this exactly against other departmental financial reporting because some expenditure within the Joint Health Command is not related to patient care and because of the accounting practices (e.g. cost accrual) employed in departmental reporting. There are also areas of health expenditure within the Department that cannot be extracted from Departmental reporting such as building maintenance and other infrastructure costs and material used within the operational environment.