Government sources: State and territory government spending

State and territory government spending

In 2020–21, state and territory governments spent $61.6 billion on health. In real terms, this was a 8.6% growth in spending from 2019–20 – an additional $4.9 billion (Table 10). This real growth was higher than the average growth rate over the period from 2010–11 to 2020–21 (3.7% per annum).

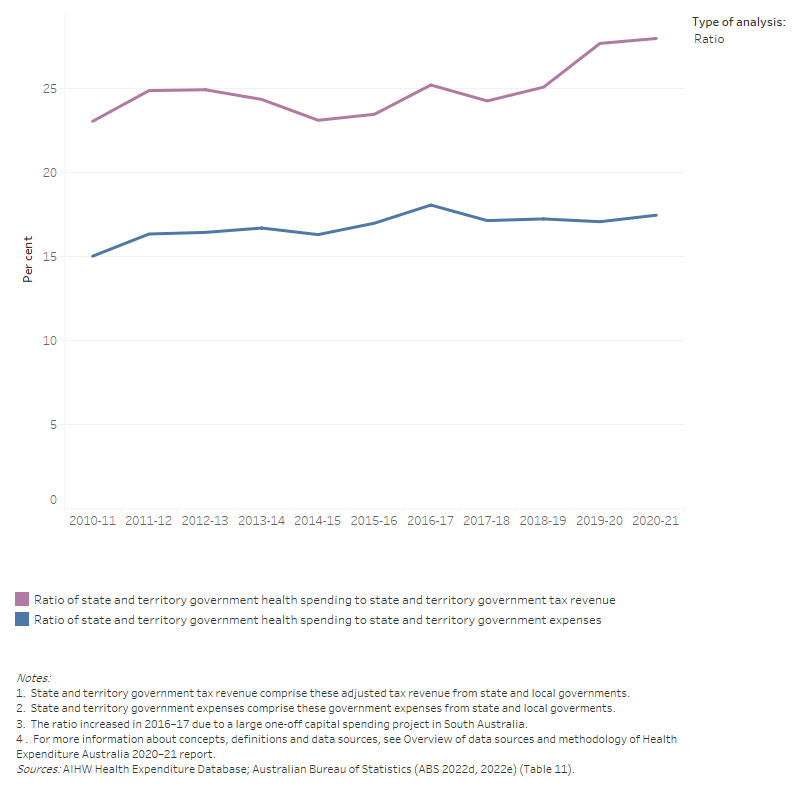

Spending relative to government expenses and taxation revenue

In 2020–21, the ratio of state and territory government health spending to their total government expenses was 17.4%, approximately 0.4 percentage points higher than in 2019–20 (Figure 14). This suggests the growth in health spending was faster than other government expenses growth as well as tax revenue growth (Table 16).

During 2020–21, health spending by state and territory governments was 28.0% of their tax revenue (Figure 14). This was 0.3 percentage points higher than 2019–20, reflecting that growth in nominal health spending (10.2%) was faster than tax revenue growth (9.1%) (Table 16).

Figure 14: Ratios of state and territory government health spending to state and territory government tax revenue and government expenses, current prices, 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows the dollar amounts of the state and territory government tax revenue, expenses and health spending with additional lines showing the ratios of the state and territory government health spending to tax revenue and government expenses as a percentage. State and territory government health spending increased from $34.1 billion in 2010–11 to $61.6 billion in 2020–21. Tax revenue increased from $148.0 billion in 2010–11 to $220.3 billion in 2020–21. Ratio of state and territory health spending to state and territory tax revenue increased over the 10-year period from 23.0 per cent to 28.0 per cent. The highest ratio of 28.0 per cent was in 2020–21. In addition, state and territory government health spending increased from $34.1 billion in 2010–11 to $61.6 billion in 2020–21. Government expenses increased from $227.3 billion in 2010–11 to $353.0 billion in 2020–21. Ratio of state and territory health spending to state and territory tax revenue increased over the 10-year period from 15.0 per cent to 17.4 per cent.

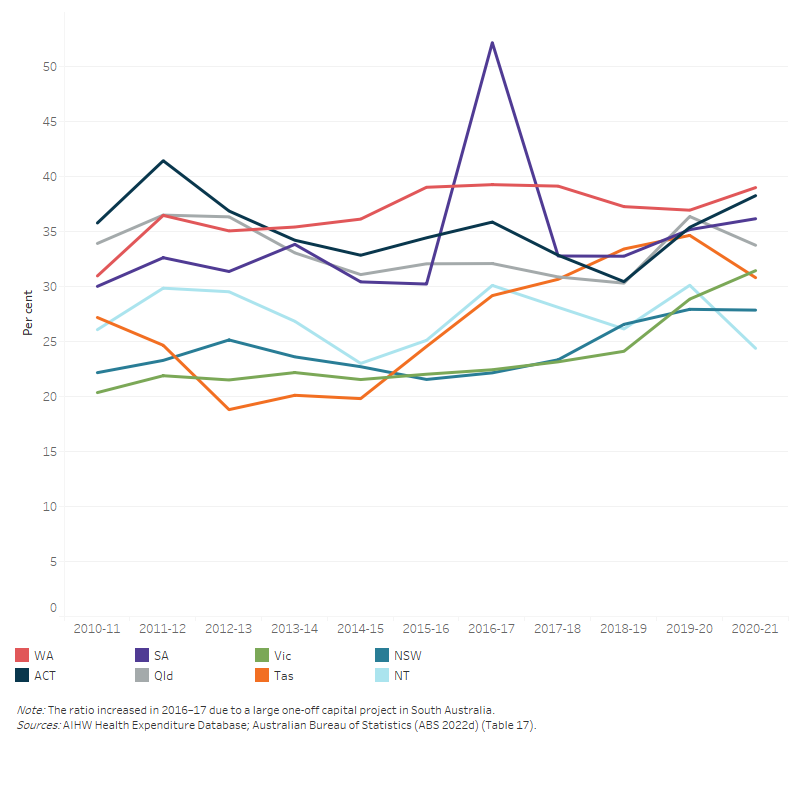

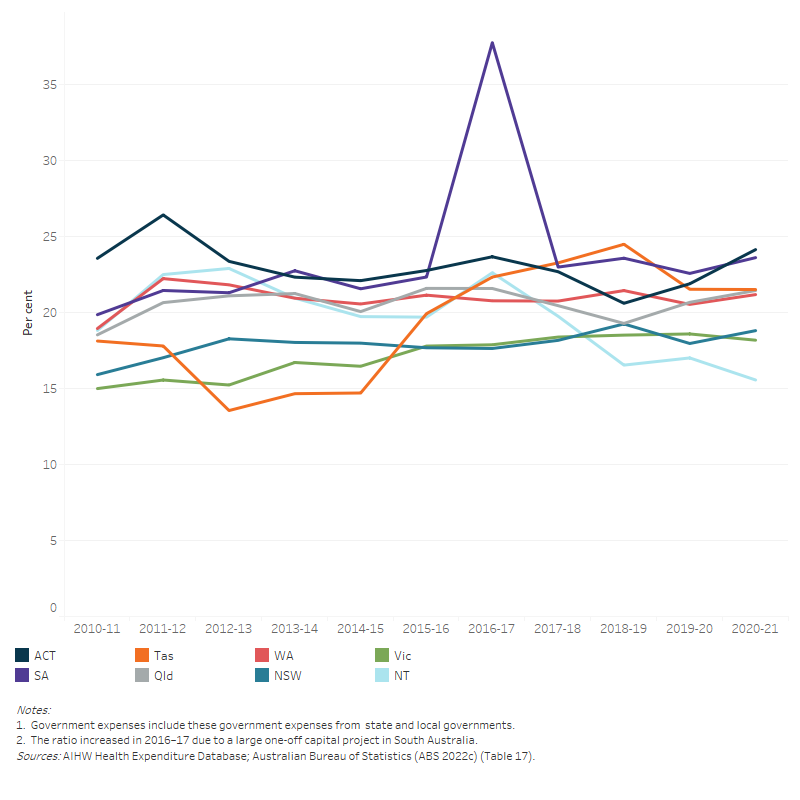

In 2020–21, the ratio of health spending to tax revenue varied across state and territories, with the highest in Western Australia (39.0%) and the lowest in the Northern Territory (24.4%) (Figure 15a). Similarly, the ratio of health spending to government expenses differed across state and territories, with the highest in the Australian Capital Territory (24.1%) and lowest in the Northern Territory (15.6%) (Figure 15b). The ratio increased for most states and territories in 2019–20 (except for Western Australia), but deviated between jurisdictions in 2020–21 (increased in Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory, while declined for the others).

Figure 15a: Ratio of total health spending to tax revenue for each state and territory government, current prices, 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that ratio of health spending to tax revenue for all states and territories from 2010–11 to 2020–21. Over the 10-year period, the list of average ratio from highest to lowest is Western Australia (36.8 per cent), the Australian Capital Territory (35.3 per cent), South Australia (34.3 per cent), Queensland (33.3 per cent), the Northern Territory (27.2 per cent), Tasmania (26.7 per cent), New South Wales (24.2 per cent) and Victoria (23.6 per cent). The ratio increased significantly in 2016–17 for South Australia due to a large one-off capital spending project.

Figure 15b: Ratio of total health spending to government expenses for each state and territory government, current prices, 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that ratio of health spending to government expenses for all states and territories from 2010–11 to 2020–21. Over the 10-year period, the list of average ratio from highest to lowest is South Australia (23.6 per cent), Australian Capital Territory (23.1 per cent), Western Australia (20.9 per cent), the Queensland (20.6 per cent), the Northern Territory (19.7 per cent), Tasmania (19.3 per cent), New South Wales (17.9 per cent) and Victoria (17.1 per cent). The ratio increased significantly in 2016–17 for South Australia due to a large one-off capital spending project.

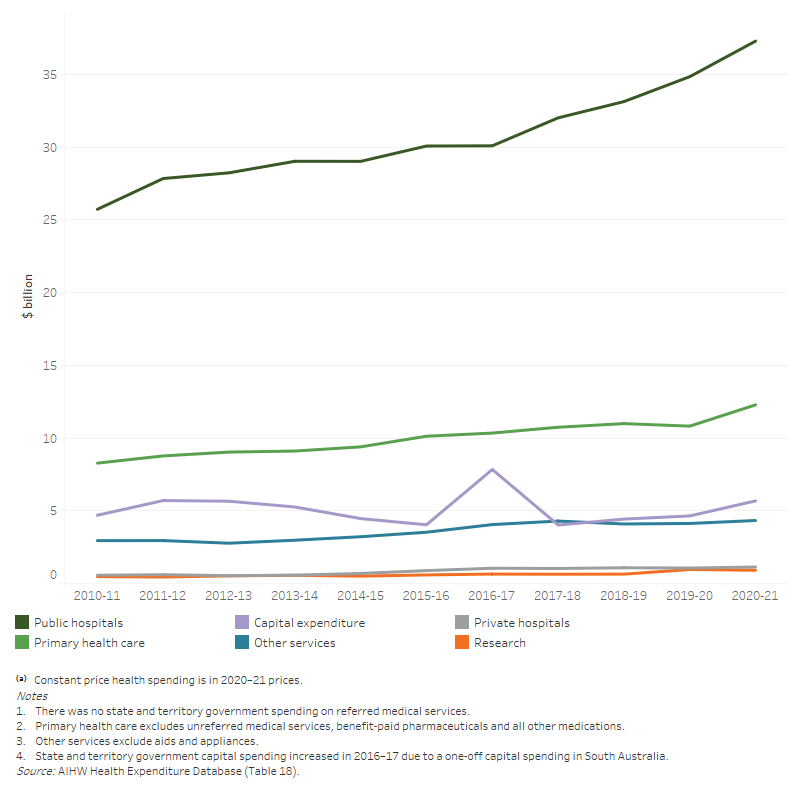

Area of spending

In 2020–21, state and territory governments spent $38.4 billion (62.3%) on hospitals, with the most ($37.3 billion) on public hospitals. Another $12.3 billion (20.0%) was spent on primary health care; $8.4 billion of which was in community health services (Figure 16; Table A6).

In 2020–21, state and territory spending increased in real terms in these main areas:

- public hospital services by $2.3 billion (6.6% increase compared with 2019–20)

- public health by $1.4 billion (92.7% increase)

- capital by $1.0 billion (22.2% increase)

- other services (patient transport services, aids and appliances, administration) by $0.2 billion (3.8% increase).

Spending on research decreased by $0.05 billion (–5.3%).

Figure 16: State and territory government total health spending, by area of spending, constant prices(a), 2010–11 to 2020–21

The line graph shows that state and territory government health spending increased from 2010–11 to 2020–21 in all areas of spending. For the overall 10-year period, the largest increase was for public hospitals ($25.7 billion in 2010–11 to $37.3 billion in 2020–21) followed by primary health care ($8.3 billion in 2010–11 to $12.3 billion in 2020–21). State and territory government health spending was relatively flatter for private hospitals, other services and research. Capital spending by state and territory government increased in 2016–17 due to a large one-off capital spending project in South Australia.

These estimates of public hospital spending differ from those reported in the NHFB statistics for a range of reasons, including where funding is provided to support public hospital service delivery outside the NHFP, differences between cash and accrual accounting practices and treatments of capital and interests. More details can be found in Comparison and alignment of Australian health expenditure estimates.