First Nations people in the National Drug Strategy Household Survey

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people are a priority population in the National Drug Strategy. Compared to other Australians, First Nations people suffer more harm from alcohol, tobacco and other drug use (Department of Health and Aged Care 2017).

The proportions presented in this article refer to people who reported they were “Aboriginal”, “Torres Strait Islander” or “both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander”. In 2022–2023 the NDSHS was not distributed in remote communities, so proportions are not considered representative of all First Nations people in Australia.

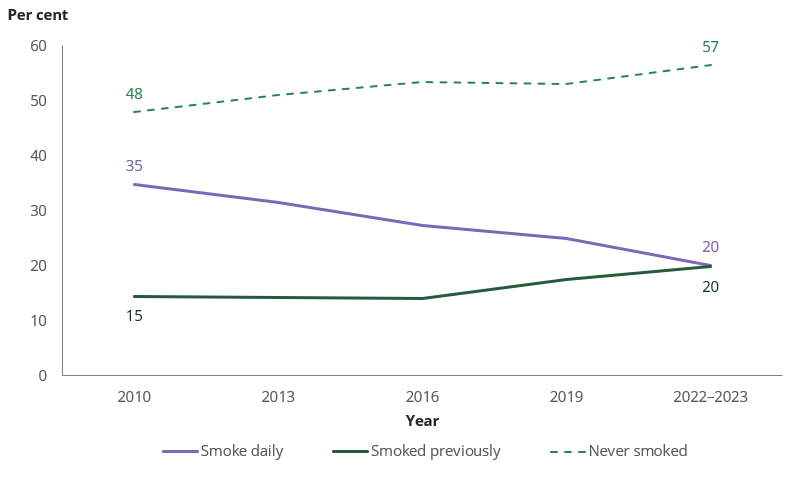

Smoking rates continued to decline, but remained high

1 in 5 (20%) First Nations people smoked tobacco daily in 2022–2023, a substantial decrease from 2010 when more than 1 in 3 (35%) smoked daily. This was due to an increase in the proportion of First Nations people who had never smoked, and a smaller increase in the proportion who smoked in the past but had stopped (Figure 1).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.1.

Smoking rates among First Nations people have historically been higher than non‑Indigenous people in the NDSHS, and this remained true in 2022–2023. After adjusting for differences in age, First Nations people were 2.6 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to smoke daily.

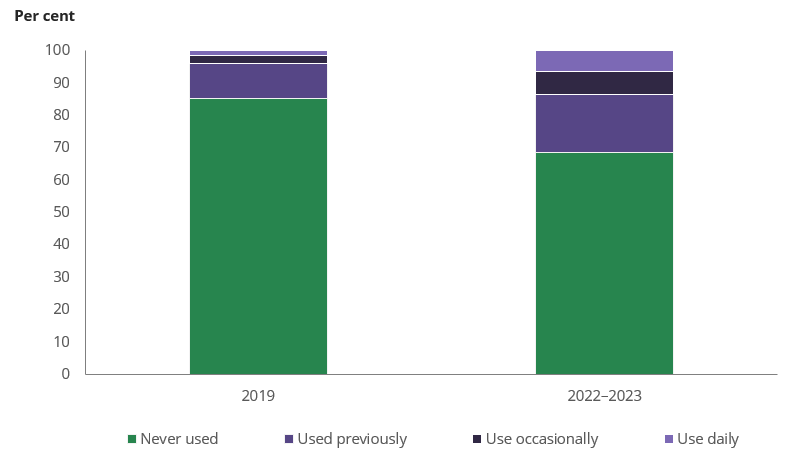

E‑cigarette use increased for First Nations people

Use of electronic cigarettes/vapes(e‑cigarettes) increased among First Nations people in 2022–2023 (Figure 2). Almost 1 in 3 (31%) First Nations people had used electronic cigarettes at least once in their lifetime, an increase from 14.6% in 2019. The proportion of First Nations people using e‑cigarettes daily also increased (from *1.6% in 2019 to 6.5% in 2022–2023), as did the proportion using them weekly, monthly or less than monthly (from *2.2% to 7.1%).

* Estimate has a relative standard error between 25% and 50% and should be interpreted with caution.

Notes:

1. Used previously refers to people who ‘Used to use them but no longer use’ or ‘Only tried them once or twice’.

2. Use occasionally includes ‘At least weekly but not daily’, ‘At least monthly but not weekly’ and ‘Less than monthly’.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 3.11.

While there has been an increase in e‑cigarette use and a decrease in smoking among First Nations people, 1 in 20 First Nations people (*5.1%) both smoked and used e‑cigarettes in 2022–2023.

Use of e‑cigarettes increased across Australia between 2019 and 2022–2023 for most population groups, and the same was true for First Nations people. However, use of e‑cigarettes was more prevalent among First Nations people than non‑Indigenous people: after adjusting for differences in age, First Nations people were 1.5 times as likely to currently use e‑cigarettes as non‑Indigenous people, and 1.3 times as likely to have used them at some point in their lifetime.

* Estimate has a relative standard error between 25% and 50% and should be interpreted with caution.

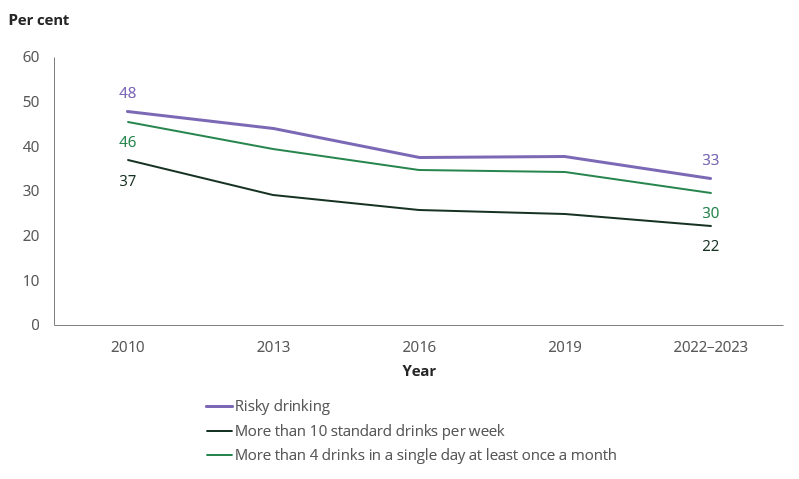

How has alcohol consumption changed among First Nations people since 2010?

Risky drinking in the NDSHS

In 2020, the National Health and Medical Research Council released new guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol.

Alcohol consumption that averages more than 10 standard drinks per week, or more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month, increases the health risks from drinking alcohol (termed risky drinking in the NDSHS).

For more information, see Measuring Risky Drinking according to the Australian Alcohol Guidelines (AIHW 2021).

Rates of risky drinking among First Nations people have declined substantially, from almost 1 in 2 (48%) in 2010 to 1 in 3 (33%) in 2022–2023 (Figure 3).

Drinking more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least monthly was the primary way that First Nations people drank alcohol at risky levels, which declined in a similar way to the overall risky drinking trend (Figure 3). There was also a decline in the proportion of First Nations people drinking more than 10 standard drinks per week on average, from 37% in 2010 to 22% in 2022–2023.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.1.

In 2022–2023, First Nations people had similar rates of risky drinking to non‑Indigenous people. Drinking behaviours, however, did differ between the two groups. After adjusting for differences in age in 2022–2023:

- First Nations people were 1.2 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to have consumed no alcohol in the previous year.

- First Nations people were 1.2 times as likely to have consumed more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month.

- Non‑Indigenous people were 1.1 times as likely to have consumed more than 10 standard drinks per week on average.

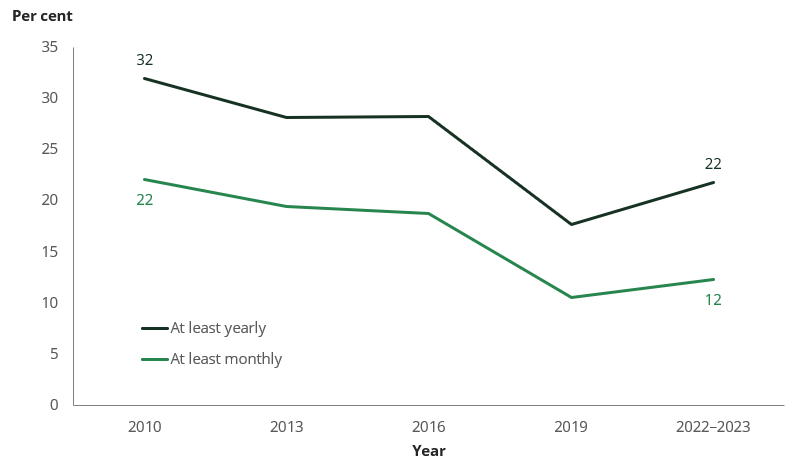

The largest difference, which is not part of the Australian alcohol guidelines, was for occasions of very high alcohol consumption. First Nations people were more likely to have consumed 11 or more standard drinks in a single day than non‑Indigenous people in 2022–2023:

- First Nations people were 1.4 times as likely to have done so in the previous year.

- First Nations people were 1.8 times as likely to have done so at least once a month in the previous year.

The proportion of First Nations people who consumed 11 or more standard drinks in a single day, either yearly or at least monthly on average, has decreased since 2010 (Figure 4). Apparent changes since 2019 were not found to be meaningful due to the small number of First Nations people surveyed in 2019 and 2022–2023.

Note: At least yearly includes those who did so at least monthly.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.1.

A changing illicit drugs landscape in 2022–2023

In 2022–2023, more than 1 in 4 (28%) First Nations people had used illicit drugs in the previous 12 months. This was consistent with previous years, however the order of the most commonly used illicit drugs did change between 2019 and 2022–2023 (Table 1).

2019 | 2022–2023 |

|---|

Cannabis (16.0%) | Cannabis (17.0%) |

Pain-killers/pain-relievers and opioids1 (5.2%*) | Cocaine (5.5%*) |

Cocaine (4.2%*) | Pain-killers/pain-relievers and opioids1 (4.6%*) |

Tranquillisers/sleeping pills1 (3.7%*) | Hallucinogens (2.9%*) |

Ecstasy (3.1%*) | Methamphetamine and amphetamine (2.7%*) |

* Estimate has a relative standard error between 25% and 50% and should be interpreted with caution.

1. Used for non‑medical purposes.

Note: Due to the small sample size, estimates for First Nations people should be interpreted with caution.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.1.

Many of these trends, such as the reduction in pain-relievers and opioids and increase in cocaine, were reflected across Australia. However, there were differences in the proportions of First Nations and non‑Indigenous people using these substances. After adjusting for differences in age in 2022–2023:

- First Nations people were 1.4 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to have used any illicit drug in the previous 12 months.

- Non‑Indigenous people were 3.3 times as likely as First Nations people to have used ecstasyin the previous 12 months.

- First Nations people were 2.3 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to have used methamphetamine and amphetaminein the previous 12 months.

- First Nations people were 2.2 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to have used pain-relievers and opioids for non‑medical purposes in the previous 12 months.