What is psychological distress?

Psychological distress is broadly defined as a state of emotional suffering characterised by symptoms of depression and anxiety. It may include loss of interest, unhappiness, desperateness, nervousness, restlessness, and feeling tense (AIHW, 2023).

Psychological distress was measured in the National Drug Strategy Household Survey using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. The scale consists of 10 questions on non‑specific psychological distress and relates to the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms a person may have felt in the preceding 4-week period. It is used only for people aged 18 and over (AIHW, 2020).

Throughout this article, results for people experiencing psychological distress include those experiencing high levels of psychological distress (a score of 22–29 on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale) and those experiencing very high levels of psychological distress (a score of 30–50).

More people are experiencing psychological distress

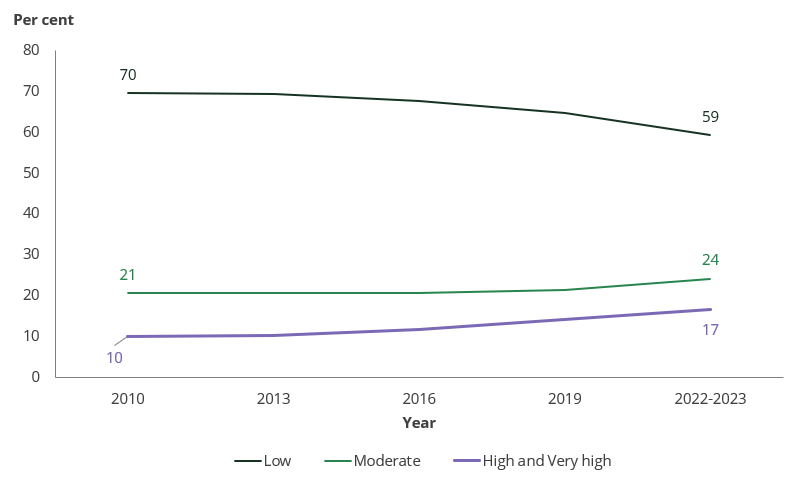

Between 2019 and 2022–2023, fewer people reported low levels of psychological distress in the National Drug Strategy Household Survey. Almost 1 in 4 people (24%) reported moderate levels of psychological distress (up from 21% in 2019), and almost 1 in 5 (16.6%) reported high or very high levels of psychological distress (up from 14.0%).

These results continue the increasing trend since 2010, when just 9.9% of the population were experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress (Figure 1).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.16.

People experiencing psychological distress more likely to smoke, vape, and drink alcohol at risky levels

Smoking among people experiencing psychological distress decreased, but remained high

People experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress were much less likely to smoke tobacco daily in 2022–2023 than in 2019, dropping from 21% to 15.3%. People experiencing low or moderate levels of psychological distress were also less likely to smoke daily (Figure 2).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.18.

Despite these reductions, people experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress were 2.3 times as likely as those experiencing low levels of psychological distress to report smoking daily.

Higher levels of psychological distress associated with higher use of e‑cigarettes/vapes

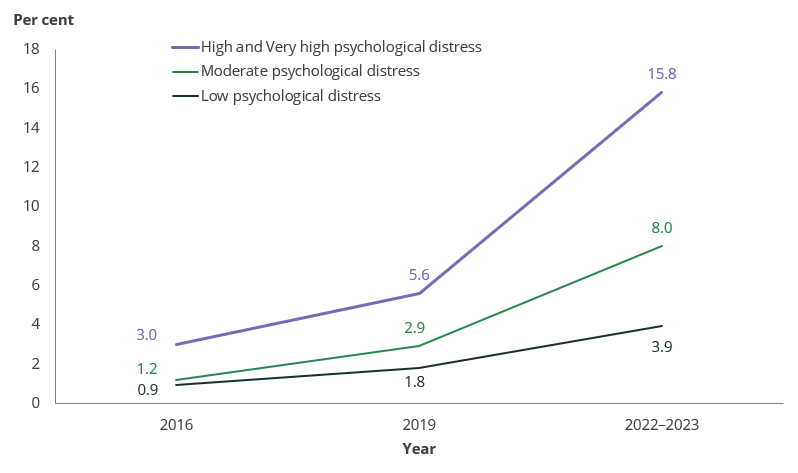

Use of electronic cigarettes and vapes (‘e‑cigarettes’) increased among almost all population groups between 2019 and 2022–2023, and the same was true among people experiencing any level of psychological distress. However, the increases were much larger among people experiencing high and very high levels of psychological distress (Figure 3).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.18.

As a result, people who were experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress were 4.1 times as likely to currently use e‑cigarettes as those who were experiencing low levels in 2022–2023.

More than 1 in 3 (35%) people experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress had used e‑cigarettes at least once in their lifetime, when just 1 in 8 (13.0%) people with low levels of psychological distress had done so.

People experiencing psychological distress were more likely to drink at risky levels than others

Risky drinking

Drinking at risky levels or ‘risky alcohol consumption’ is defined as consuming more than 10 standard drinks per week on average or having more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month over the previous 12 months (NHMRC, 2020).

In 2022–2023, people experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress were more likely than those who reported low levels of psychological distress to consume alcohol in ways that put their health at risk (39% compared with 30%).

People experiencing psychological distress were also more likely to drink more than 10 standard drinks per week on average (30% compared with 25%) and to consume more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month (33% compared with 22%).

Risky drinking behaviours did not change substantially between 2019 and 2022–2023 for people experiencing either low or high and very high levels of psychological distress.

Illicit drug use more common among those experiencing psychological distress

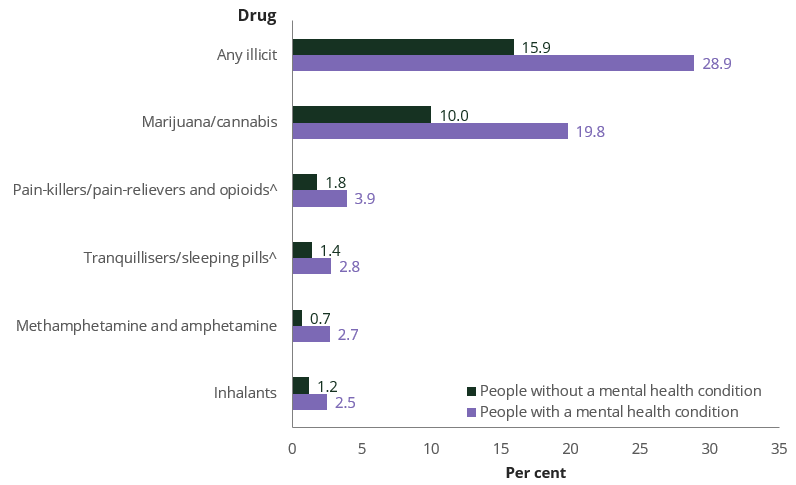

^ Used for non‑medical purposes.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.18.

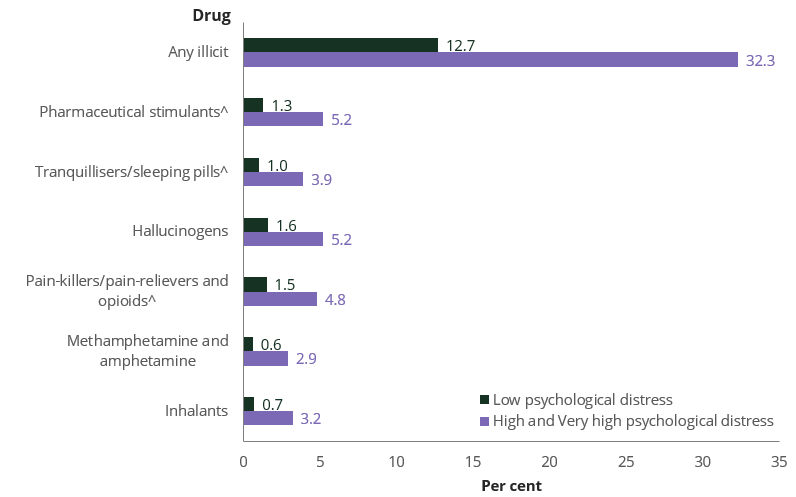

Similar to previous years, in 2022–2023 people who experienced high and very high levels of psychological distress were more likely than those who experienced low levels to have used illicit drugs in the previous 12 months (Figure 4). While around 1 in 8 (12.7%) people experiencing low levels of psychological distress had used any illicit drug in the previous 12 months, almost 1 in 3 (32%) people experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress had done so, similar to the proportion in 2019 (31%).

Compared with people aged 18 and over who reported low psychological distress, people experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress were:

- 2.5 times as likely to have used any illicit drug (32% compared with 12.7%).

- 4.8 times as likely to have used methamphetamine and amphetamine (2.9% compared with 0.6%).

- 4.6 times as likely to have used inhalants (3.2% compared with 0.7%).

- 4.0 times as likely to have used pharmaceutical stimulantsfor non‑medical purposes (5.2% compared with 1.3%).

- 3.9 times as likely to have used tranquillisers/sleeping pills for non‑medical purposes (3.9% compared with 1.0%).

- 3.3 times as likely to have used hallucinogens(5.2% compared with 1.6%).

- 3.2 times as likely to have used pain-relievers and opioids for non‑medical purposes (4.8% compared with 1.5%).

Mental illness increased among the Australian population

What is mental illness?

Mental illness refers to a clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour, usually associated with distress or impairment in important areas of functioning (COAG Health Council, 2017). The Australian Government has made mental health a priority area for prevention and investment, with acknowledgement that there is substantial comorbidity of mental ill-health and substance use (Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

In the NDSHS, people who reported that they had been diagnosed or received treatment for depression, an anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, other form of psychosis or an eating disorder in the previous 12 months are defined as having a mental health condition. The terms ‘mental illness’ or ‘mental health condition’ are used interchangeably throughout the article.

The proportion of people aged 18 and over who reported experiencing any mental illness increased from 16.9% in 2019 to 18.0% in 2022–2023. This continues the increasing trend in mental health conditions occurring since 2010, when 12.0% of the population reported that they had been diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition.

The relationship between mental illness and drug use

A mental illness may make a person more likely to use drugs—for example, for short-term relief from their symptoms—while other people may have drug problems that trigger the first symptoms of mental illness. Some drugs cause drug-induced psychosis, which is usually brief. However, if someone has a predisposition to a psychotic illness such as schizophrenia, the use of illicit drugs may trigger the first episode in what can be a chronic mental illness (Sane Australia 2017). The use of drugs can interact with mental illness in ways that create serious adverse effects on many areas of functioning, including work, relationships, health, and safety.

People with a mental health condition more likely to smoke, vape, and drink at risky levels

Smoking higher among people with a mental health condition

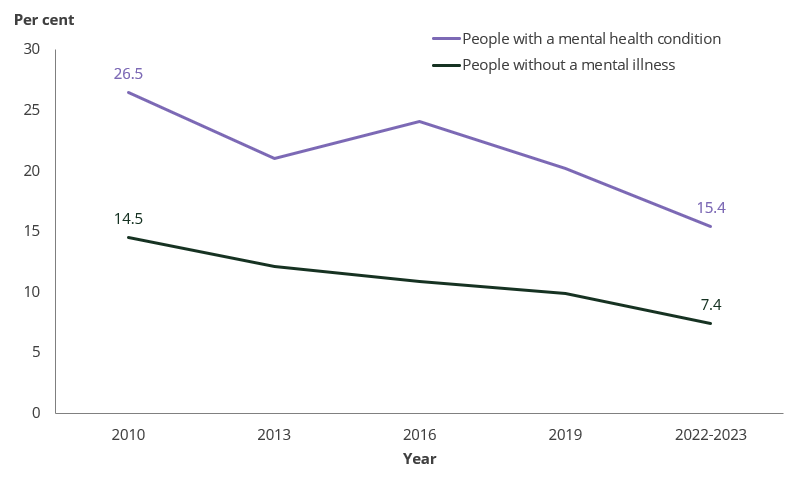

People aged 18 and over who were diagnosed with or treated for a mental health condition were less likely to smoke tobacco daily in 2022–2023 (15.4%) than in 2019 (20%). A similar decrease in daily smoking occurred among those without a mental health condition (Figure 5).

The trend since 2010 has shown a persistent gap in daily smoking, with people who were experiencing a mental health condition being at least 1.8 times as likely to smoke daily compared as those without a mental health condition.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.20.

E‑cigarette use more common among people with a mental health condition

In 2022–2023, people with a mental health condition were more likely to have used e‑cigarettes than those who did not have a mental health condition. People who had been diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition were:

- 2.1 times as likely to currently use e‑cigarettes (12.3% compared with 5.8% of people without mental illness).

- 1.7 times as likely to have used e‑cigarettes at some point in their lifetime (30% compared with 17.4%).

High but stable levels of risky drinking among people with a mental health condition

Between 2019 and 2022–2023, the proportion of people with a mental health condition who reported drinking at risky levels remained stable (37%). The rate has not changed substantially since 2013, when 39% of people with a mental health condition reported risky alcohol consumption.

Illicit drug use more common among people with a mental health condition

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 10.20.

In 2022–2023, people with a mental health condition were more likely to have used illicit drugs in the previous 12 months than people without a mental health condition (Figure 6). Around 1 in 4 (29%) people who reported having a mental health condition had done so, compared to around 1 in 6 people (15.9%) without a mental health condition.

Recent use of all illicit drugs was higher among people who had been diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition than those who had not. The most substantial differences, as shown in Figure 6, were:

- 1.8 times as likely to have used any illicit drug (29% compared with 15.9%).

- 3.9 times as likely to have used methamphetamine and amphetamine (2.7% compared with 0.7%).

- 2.2 times as likely to have used pain-relievers and opioids (3.9% compared with 1.8%).

- 2.1 times as likely to have used inhalants (2.5% compared with 1.2%).

- 2.0 times as likely to have used tranquillisers/sleeping pills (2.8% compared with 1.4%).

- 2.0 times as likely to have used cannabis (19.8% compared with 10.0%).