Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol 2020

In December 2020, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) released revised Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol.

Data on alcohol consumption from the 2022–2023 NDSHS were analysed according to the revised Australian alcohol guidelines. The calculation is based on previous work measuring risky drinking according to the Australian alcohol guidelines (AIHW 2021). All results in this report from 2001 to 2022–2023 have been calculated against the revised guidelines released in 2020.

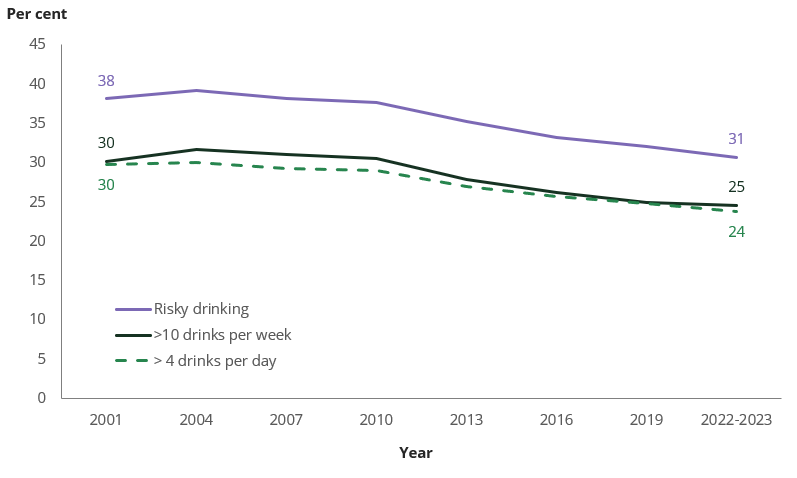

Risky alcohol consumption remains stable

In 2022–2023, about 1 in 3 people (31% or 6.6 million people) aged 14 and over consumed alcohol in ways that put their health at risk. This was similar to 2019, when 32% of the population (around 6.7 million people) reported drinking at risky levels.

What is risky alcohol consumption?

In the 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey, “drinking at risky levels” or “risky drinking” is defined according to the Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

Guideline 1 advises that “To reduce the risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury, healthy men and women should drink no more than 10 standard drinks a week and no more than 4 standard drinks on any one day”. As a result, a person doing either or both of the following will be classified as having consumed alcohol in ways that increased their risk of harm:

- Having more than 10 standard drinks per week on average in the previous 12 months.

- Having more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month over the previous 12 months.

While exceeding either of these recommendations is classified as risky drinking, each drinking behaviour is also presented separately to show differences in alcohol consumption patterns across the population.

Alcohol consumption has many associated harms and risks beyond the health impacts to the person consuming alcohol. Further information can be found in Alcohol-related harms and risks in the NDSHS.

The 2022–2023 NDSHS continued a trend of gradually declining risky drinking in Australia since 2004, when 39% of the population consumed alcohol at risky levels (Figure 1).

Similar trends occurred among people drinking more than 10 standard drinks per week on average (32% in 2004 compared with 25% in 2022–2023) and more than four standard drinks in a single day at least once a month (30% in 2004 compared with 24% in 2022–2023). The rates of risky alcohol consumption have continued to decrease at a faster rate since 2010.

Note: Data from 2001 to 2019 have been re-analysed according to the Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 4.27.

Among those who did drink alcohol, people who drank at levels that put their health at risk were most likely to view themselves as ‘social drinkers’ (43%) and ‘light drinkers’ (23%). For people who did not drink at risky levels, they were most likely to view themselves as ‘occasional drinkers’ (52%) and ‘light drinkers’ (21%).

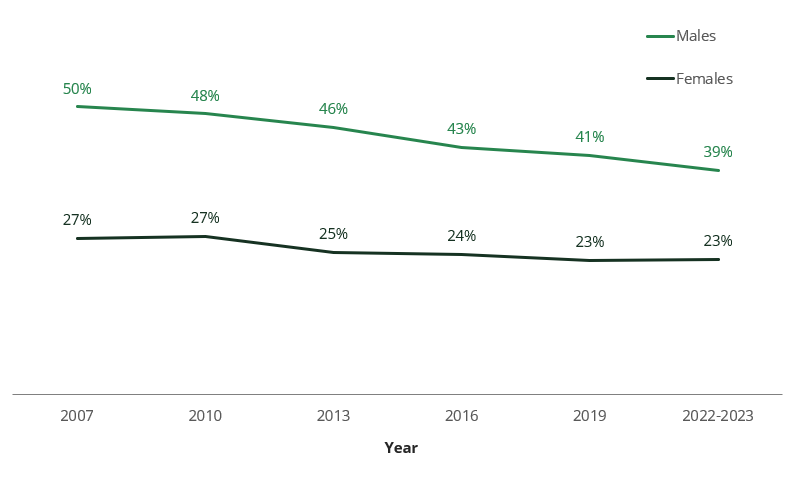

Fewer young males drinking at risky levels, but young female risky drinking remained steady

Between 2019 and 2022–2023, the proportion of people who drank at risky levels did not change substantially at the national level. However, this trend was not the same for males and females.

Consistent with previous NDSHS surveys, in 2022–2023, males (39%) were more likely to drink at risky levels than females (23%). The proportion of males drinking at risky levels decreased from 41% in 2019 to 39% in 2022–2023, while the proportion of females doing so remained stable.

The reduction in risky alcohol consumption among males reflects a long-term downward trend, from 50% in 2007 to 39% in 2022–2023. A similar trend occurred among females, but the change was relatively small (from 27% in 2007 to 23% in 2022–2023) (Figure 2).

Note: Data from 2007 to 2019 have been re-analysed according to the Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 4.28.

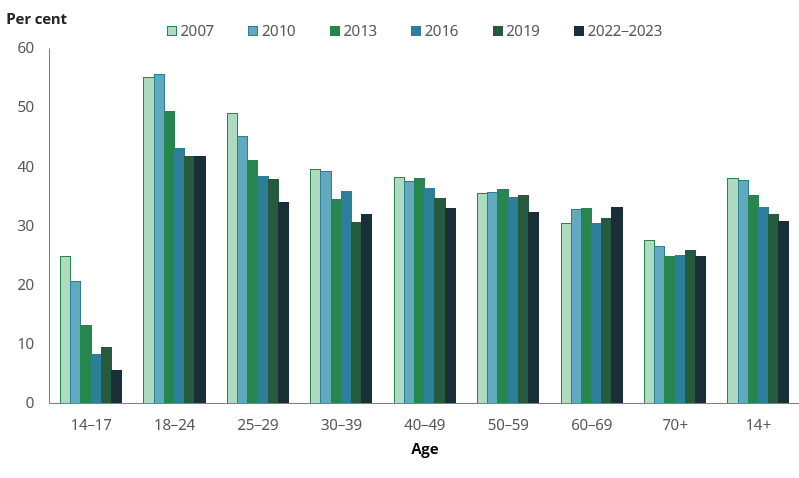

Risky drinking remains stable in almost all age groups

Fewer young people aged 14–17 drank alcohol at risky levels in 2022–2023 (5.5%), down from 9.5% in 2019. The reduction in risky drinking among males in this age group, from 9.9% in 2019 to just *3.2% in 2022–2023, accounted for the reduction.

* Estimate has a relative standard error between 25% and 50% and should be interpreted with caution.

Outside of a reduction in risky drinking among young people aged 14–17, there were very few meaningful changes in risky drinking in all age groups (Figure 3). This was despite the new recommendations for reducing health risks from drinking alcohol being released between 2019 and 2022–2023, which recommended lower levels of alcohol consumption than the previous alcohol guidelines.

Note: Data from 2007 to 2019 have been re-analysed according to the Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 4.28.

As a result, just as in 2019, people aged 18–24 were the most likely to consume alcohol at risky levels, with around 2 in 5 (42%) doing so. Risky drinking in other age groups was very similar, with around 1 in 3 people from ages 25 to 69 drinking at risky levels in 2022–2023 (ranging from 32% to 34%), but was lower among people aged 70 and over (25%).

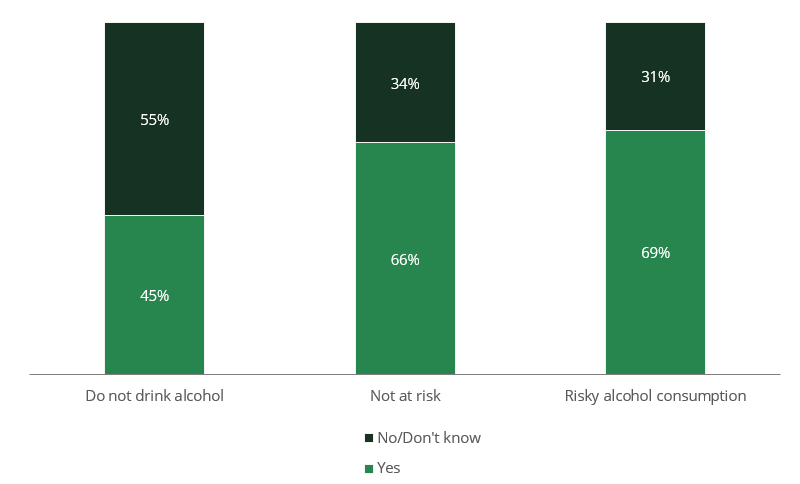

Many risky drinkers were aware of alcohol guidelines

The alcohol guidelines aim to inform people of the health risks that may be associated with their alcohol consumption, so that they can make informed decisions about the amount of alcohol they consume (NHMRC 2020). As such, it is important to understand whether people are aware of the guidelines in the first place.

In 2022–2023, the National Drug Strategy Household Survey included a question on whether people were aware that Australia has alcohol guidelines that provide advice how to reduce the health risks from drinking alcohol.

About 7 in 10 people (69%) aged 14 and over who drank alcohol at risky levels had heard of the guidelines (Figure 4). This was higher than the proportion of those who drank alcohol in ways that reduced the health risks from drinking alcohol (66%), and people who did not drink alcohol in the previous 12 months (45%).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Tables 4.43.

This is a positive story in some ways, but indicates that there is still work to be done in this space. Awareness of alcohol advice was highest among those who most need to know the advice: people who consumed the most alcohol. However, 31% of the people who put their health at risk from their own alcohol consumption were not aware that Australia had any advice on how to reduce their health risks from drinking alcohol, which represents a large portion of the Australian population that may be taking on health risks of which they were not aware.

Who was most likely to drink at risky levels?

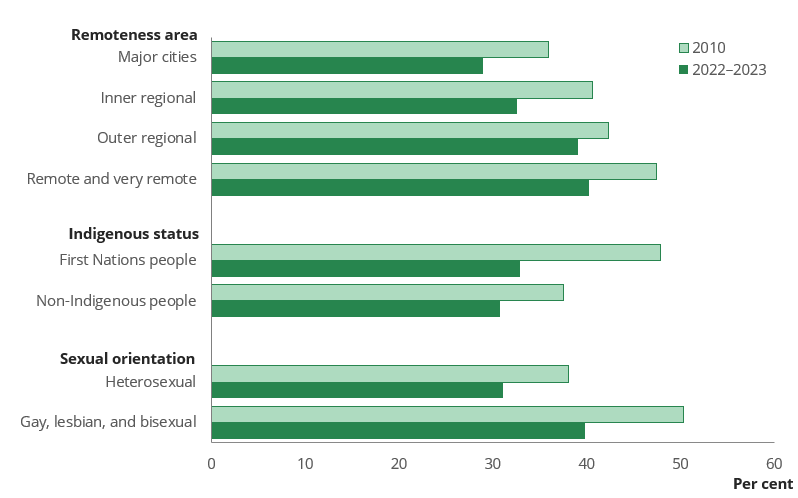

While risky consumption of alcohol was consistent between 2019 and 2022–2023 across almost all population groups, reductions occurred between almost all population groups between 2010 and 2022–2023 (Figure 5).

Notes

Data from 2010 have been re-analysed according to the Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

Rates for First Nations people should not be directly compared to rates for non‑Indigenous people due to differences in the age structures between the two populations. Age standardised results can be found in the supplementary data tables.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 4.35.

As in previous years, people who lived in Remote and Very remote areas (40%) and Outer regional areas (39%) were 1.4 times as likely as those living in the Major cities (29%) to put their health at risk from drinking alcohol in 2022–2023. Risky drinking has declined over time across all remoteness areas (Figure 5), and the difference between Remote and Very remote areas and Major cities has remained stable over time.

1 in 3 (33%) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people consumed alcohol at risky levels in 2022–2023, with over 1 in 5 (22%) First Nations people consuming more than 10 standard drinks per week on average and 3 in 10 (30%) consuming more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month.

After adjusting for differences in age, First Nations people were 1.1 times as likely to drink alcohol at risky levels as non‑Indigenous people in 2022–2023, a similar difference to 2010. However, individual risky drinking behaviours did show changes over the same time. After adjusting for differences in age between the two populations:

- First Nations people were 1.2 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to consume more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month, down from 1.4 times as likely in 2010.

- First Nations people were less likely than non‑Indigenous people to consume an average of more than 10 standard drinks per week (0.9 times as likely), down from 2010 when they were 1.1 times as likely to do so.

Gay, lesbian and bisexual people were more likely to drink at risky levels (40%) than heterosexual people (31%). This was consistent with previous surveys, and in both 2010 and 2022–2023, after adjusting for differences in age, gay, lesbian, and bisexual people were 1.2 times as likely as heterosexual people to drink alcohol at risky levels.