Table 1: Summary of ecstasy use among people aged 14 and over in 2022–2023Lifetime use | 13.6% (2.9 million people) |

|---|

Recent use1 | 2.1% (400,000 people) |

|---|

Change since 2019 | ~ Lifetime use (12.5%) ⬇ Recent use (3.0%) |

|---|

Change since 2004 | ⬆ Lifetime use (7.5%) ⬇ Recent use (3.4%) |

|---|

Opportunity to use in the last 12 months2 | 6.7% |

|---|

Age group most likely to use | 20–29 (7.5%) |

|---|

Average age of first use | 21.7 years |

|---|

Table 2: Summary of ecstasy use among people who had used it in the previous 12 months in 2022–2023Used monthly or more often | 9.8% (2019: 17.3%) |

|---|

Main form used | Capsules: 43% |

|---|

Diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition | 25% |

|---|

High and Very high psychological distress | 35% |

|---|

Notes

1. Refers to use of ecstasy in the previous 12 months.

2. Proportion of people who had been offered ecstasy or otherwise had the opportunity to use ecstasy in the previous 12 months.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023.

Disruptions in supply and opportunities to use ecstasy resulted in lower use in 2022–2023

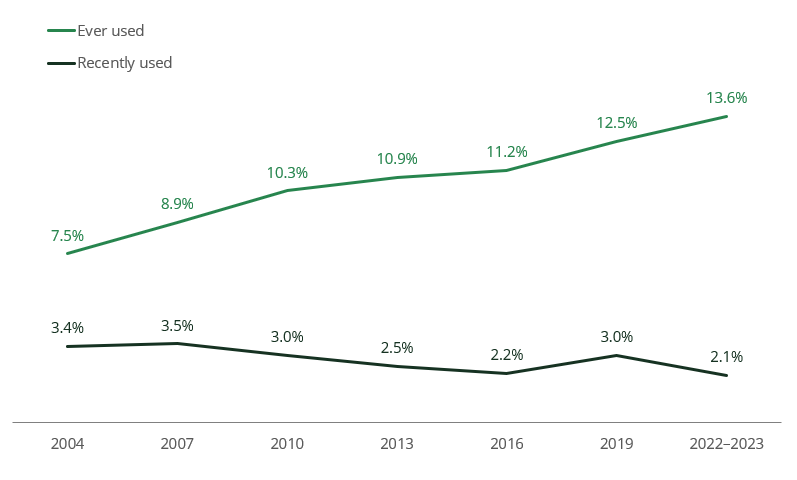

In 2022–2023, about 400,000 people had used ecstasy in the previous 12 months, equating to 2.1% of the population. This was low, relative to both the number of people who had recently used ecstasy in 2019 (about 600,000) and to the number of people in 2022–2023 who had used ecstasy at some point in their lifetime (about 2.9 million).

As a result, 2022–2023 showed the lowest levels of recent ecstasy use of all years since 2004, despite having the highest proportion of people who had ever used ecstasy (Figure 1).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Tables 5.71 and 5.73.

This may have been caused, to some extent, by disruptions to the ecstasy supply between 2019 and 2022. Seizures of ecstasy, and detections of ecstasy laboratories, decreased markedly between 2019–20 and 2020–21 (ACIC 2023). Further evidence from interviews with people who regularly use ecstasy and other stimulants did show some disruption to the ecstasy market in 2022, but an improvement in 2023:

- People interviewed between April and July 2022 were more likely to describe ecstasy as ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ to obtain compared to 2021.

- People interviewed between April and July 2023 were more likely to describe ecstasy as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain in 2023 compared to 2022 (NDARC 2022, 2023).

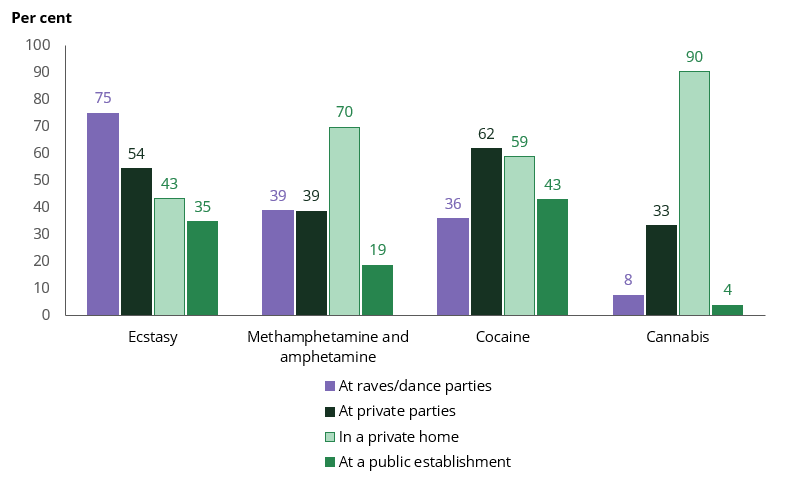

COVID-19 may have had a larger impact on the recent use of ecstasy than other drugs not only because of supply disruptions, but also due to the occasions where people tend to use ecstasy. In all years since 2010, people were most likely to usually use ecstasy at raves/dance parties, increasing from 62% in 2010 to 75% in 2022–2023. Other drugs were much less likely to have been used at raves/dance parties (Figure 2), meaning that a reduction in the number of events following COVID-19 related public health measures (particularly relevant in the 12 month period leading up to the 2022 data collection period, as not all events such as raves and dance parties had returned) is likely to have had a larger impact on ecstasy than other drugs.

Note: Respondents could select more than one location.

(a) Used in the previous 12 months.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 5.36.

Use of ecstasy showing early signs of rising again

The reduction in the use of ecstasy following supply issues and COVID-19 related public health measures means that use is likely to increase again once events pick up and supply improves. Early signs from the 2022–2023 NDSHS provide evidence that this has already begun.

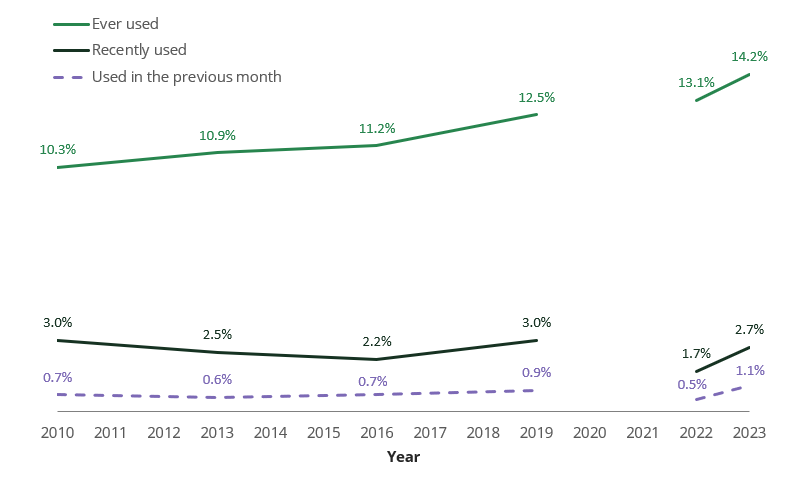

The NDSHS was conducted over two fieldwork periods:

- 20 July to 18 December 2022

- 20 March to 31 May 2023.

By examining these two fieldwork periods separately (Figure 3), the reduction in recent use of ecstasy between 2019 and 2022 is more apparent, dropping from 3.0% to 1.7% of people. Results from 2023, however, show levels rebounding, with the proportion of people using ecstasy in the previous 12 months back to pre-2019 levels (2.7%) and use of ecstasy in the previous month higher than 2019 (1.1% of the population).

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Tables 5.15 and 5.80.

These results indicate that the lower use of ecstasy in 2022–2023 is likely to be a temporary reduction, and use may already be increasing again.

Who was most likely to have used ecstasy?

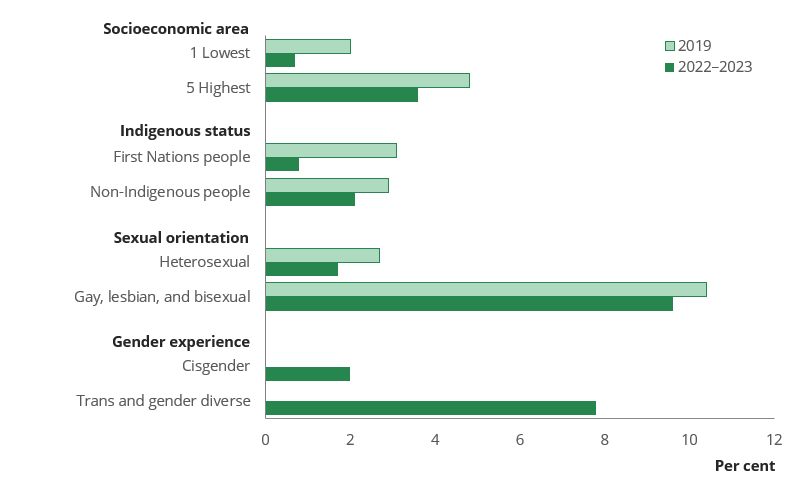

As with all illicit drugs, use of ecstasy was not uniform across the Australian population in 2022–2023 (Figure 4).

Note: Rates for First Nations people should not be directly compared to rates for non‑Indigenous people due to differences in the age structures between the two populations. Age standardised results can be found in the supplementary data tables.

Source: NDSHS 2022–2023, Table 5.76.

The largest differences in the recent use of ecstasy in 2022–2023 were:

- Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people were more likely to have used ecstasy in the previous 12 months than heterosexual people (9.6% compared to 1.7%). After adjusting for differences in age, gay, lesbian and bisexual people were 3.4 times as likely as heterosexual people to have done so. This difference was larger than in 2019, due to a substantial reduction in the use of ecstasy among heterosexual people between 2019 and 2022–2023.

- People living in the most advantaged socioeconomic areas were 5.1 times as likely as people living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas to have done so (3.6% compared to 0.7%). There was a considerable reduction in the use of ecstasy among people living in the most disadvantaged areas between 2019 and 2022–2023.

- Trans and gender diverse people were 3.9 times as likely as cisgender people to have used ecstasy in the previous 12 months in 2022–2023 (*7.8% compared to 2.0%).

- There was a reduction in the use of ecstasy among First Nations people between 2019 (*3.1%) and 2022–2023 (*0.8%). As a result, even though use of ecstasy was similar between First Nations people and non‑Indigenous people in 2019, non‑Indigenous people were 3.3 times as likely as First Nations people to have recently used ecstasy in 2022–2023 (after adjusting for differences in age structure).

* Estimate has a Relative Standard Error between 25% and 50% and should be interpreted with caution.