Induction of labour

Induction is an intervention to stimulate the onset of labour. It is performed for a number of reasons related to both the mother and the baby, such as maternal or baby medical conditions and post-term pregnancy (Coates et al 2020). For more information, see Clinical commentary.

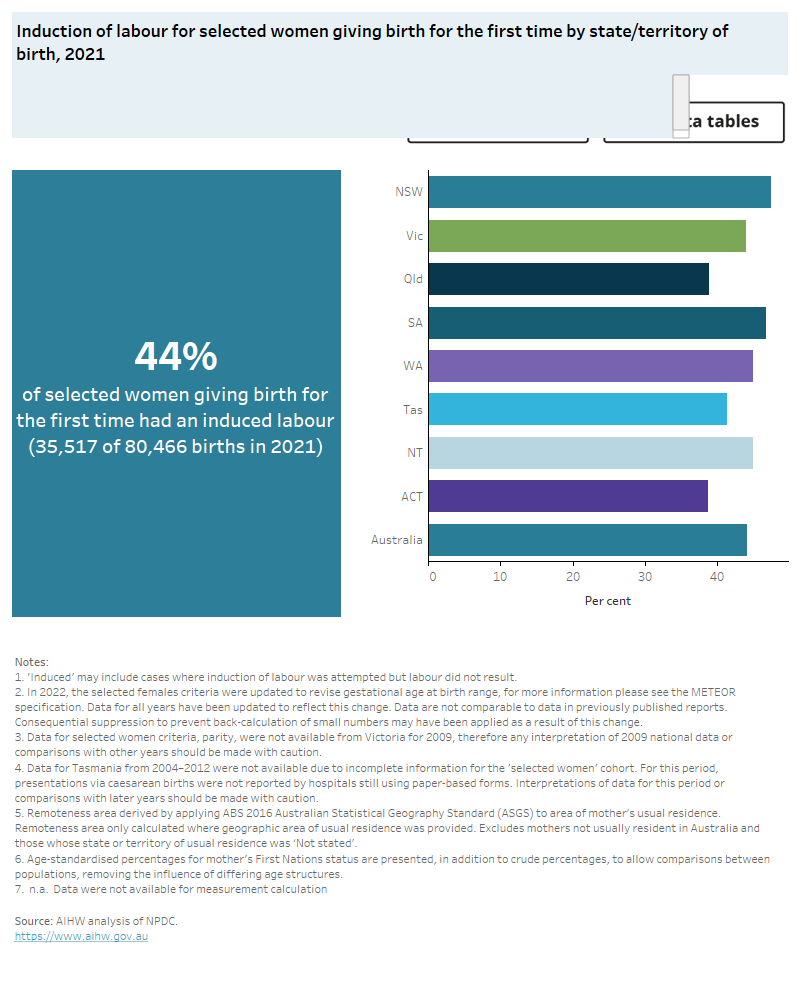

This indicator looks at induction of labour for selected women giving birth for the first time.

Key findings

In 2021, 44% of selected women giving birth for the first time had an induced labour.

The proportion of selected women giving birth for the first time who had induced labour:

- increased from 26% in 2004 to 44% in 2021, with most of the increase occurring over the last decade

- was slightly higher in public hospitals (46% in 2021) compared with private hospitals (43% in 2021) since 2016

- was lowest in the ACT and Queensland (39%) in 2021.

The interactive data visualisation (Figure 6) presents data on induction of labour in selected women giving birth for the first time by selected maternal characteristics. Select the trend button to see how data have changed between 2004 and 2021.

Figure 6: Induction of labour

Induction of labour for selected women giving birth for the first time, 2004 to 2021.

This chart shows the proportion of induced labour for selected women giving birth for the first time, for the current data 2021 and trend data from 2004 to 2021. The proportion for selected women induced in giving birth for the first time increased from 26% in 2004 to 44% in 2021.

Clinical commentary

When induction of labour is indicated on medical grounds, it is undertaken when the risks of continuing the pregnancy are greater than the risks associated with being born (McDonnell 2011). For the woman to make a fully informed decision, clear information should be given regarding the risks of continuing the pregnancy and awaiting the spontaneous onset of labour versus the risks of the intervention of induction.

Maternal factors such as wellbeing, cervical assessment, parity and previous mode of delivery, and fetal factors such as gestational age, growth and wellbeing of the fetus need to be considered when deciding whether labour should be induced (McCarthy and Kenny 2013). These factors also assist in determining the method of induction, which can be surgical (including artificial rupture of membranes) and/or medical (including use of prostaglandins and/or oxytocin) (RANZCOG 2021; Queensland Health 2017).

There are numerous indications for induction of labour. Prolonged pregnancy is the most common indication, with births after 42 weeks associated with increased risk for the baby and perinatal death (Gulmezoglu et al. 2012). It is widely recommended that induction be offered to women at 41–42 weeks of gestation (Gulmezoglu et al. 2012; NICE 2008; Queensland Health 2017).

Whilst most women who have induced labour – and their babies – do well, induction of labour does increase the risk of emergency caesarean section, infection and bleeding, and a less positive birth experience when compared to spontaneous labour (Coates et al. 2020; Grivell et al. 2012).

Indicator specifications and data

Excel source data tables are available from the Data page.

For more information refer to Specifications and notes for analysis in the technical notes.

Coates D, Makris A, Catling C, Henry A, Scarf V, Watts N, Fox D, Thirukumar P, Wong V, Russell H and Homer C (2020) ‘A systematic scoping review of clinical indications for induction of labour’, PLOS One, 15(1): e0228196, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228196.

Gulmezoglu AM, Crowther CA, Middleton P and Heatley E (2012) ‘Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6:CD004945, doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004945.pub4.

Grivell RM, Reilly AJ, Oakey H, Chan A and Dodd JM (2012) ‘Maternal and neonatal outcomes following induction of labour: a cohort study’, ACTA Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(2):198-203, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01298.x.

McDonnell R (2011) ‘Induction of labour’, O&G Magazine, 13(3):62–4.

McCarthy FP & Kenny LC (2013) ‘Induction of labour’, Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine, 24(1):9–15.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) (2008) Induction of labour: NICE clinical guideline 70, NICE, Manchester.

Queensland Health (2017) Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program 2017, Queensland maternity and neonatal clinical guideline: induction of labour. Brisbane: Queensland Health.

RANZCOG (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) (2021) Induction of labour, accessed 17 August 2022.