Study cohort – Children on care and protection orders in 2014–17

Introduction

Children on care and protection orders (CPO) are an important sub-group of clients experiencing homelessness.

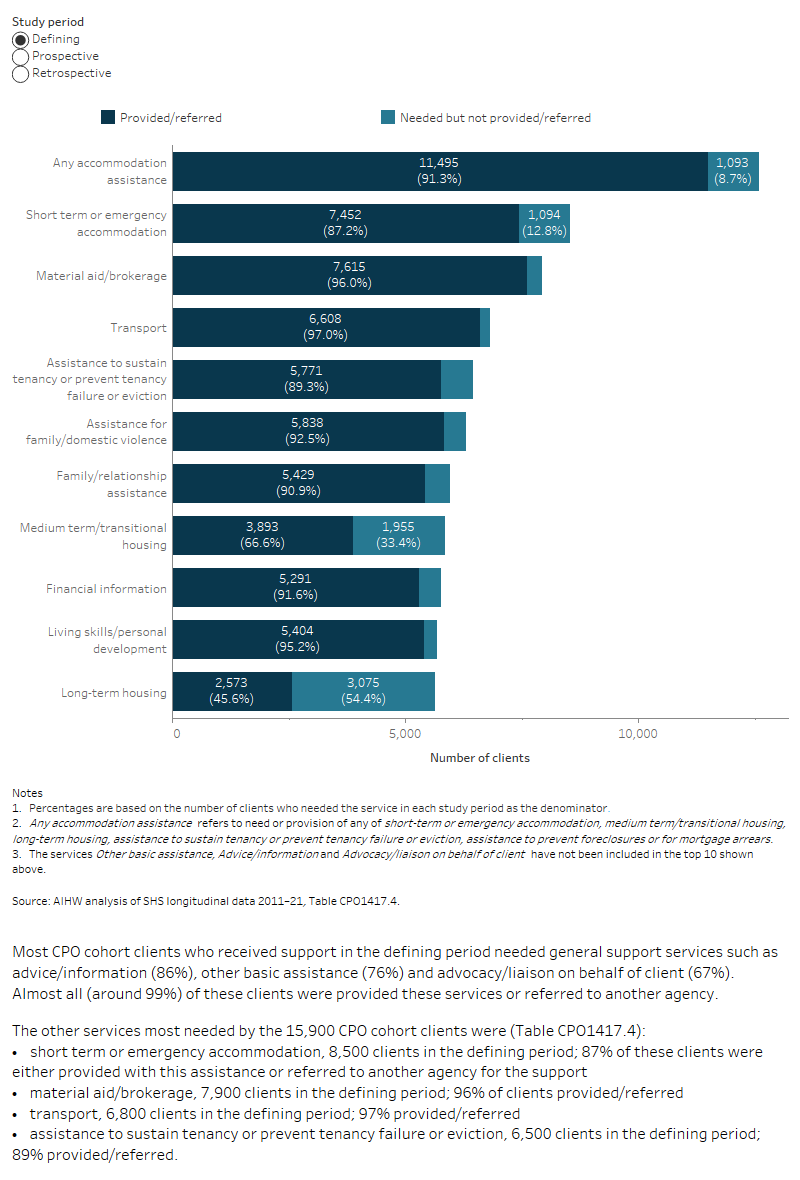

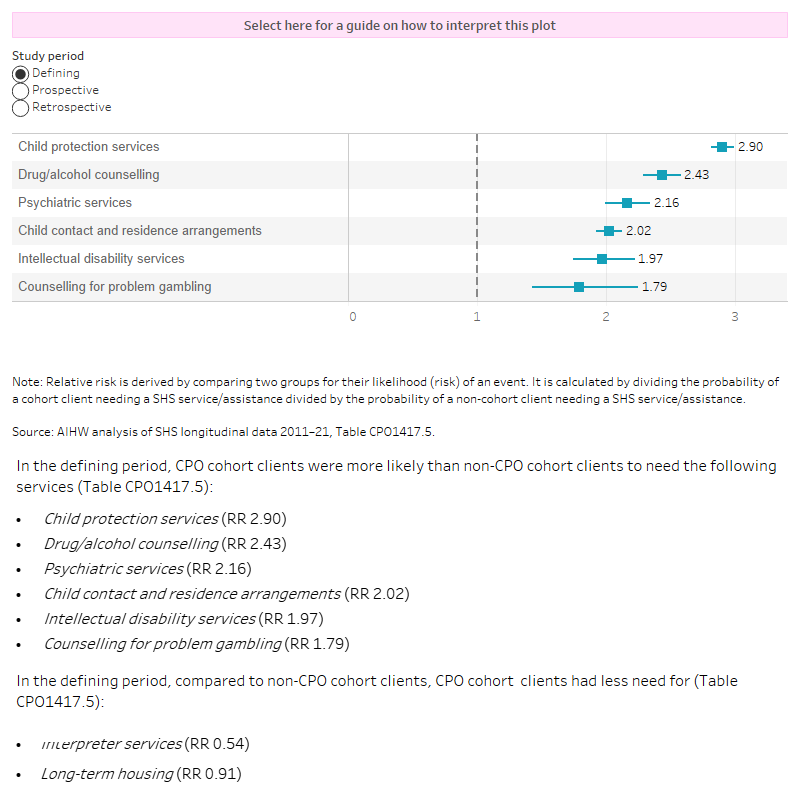

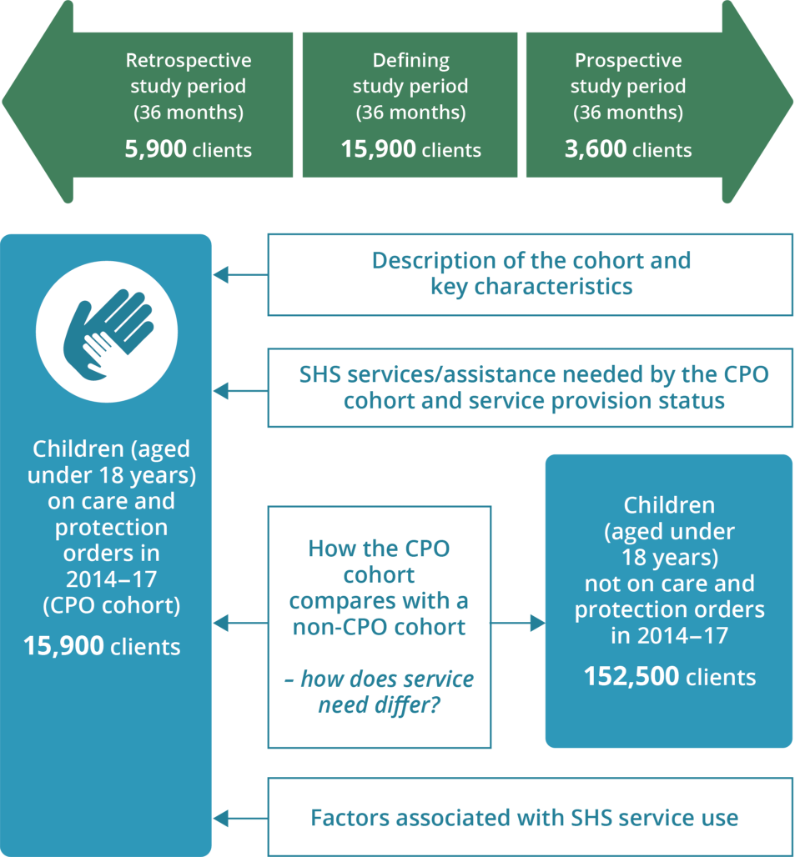

The Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) longitudinal data set was used to analyse SHS support patterns for a cohort of children receiving services in 2014–17 (see Introduction to the SHS longitudinal data for detailed information on the longitudinal analyses approach).

The CPO 2014–17 cohort was defined as clients who received SHS support in 2014–17, who were under 18 and were on a CPO either the week before presenting for a service or on presentation and had the following care arrangements:

- residential care

- family group home

- relatives/kin/friends who are reimbursed

- foster care

- other home-based care (reimbursed)

- relatives/kin/friends who are not reimbursed

- independent living

- other living arrangements

- parents.

The cohort also includes clients aged under 18 who reported ‘transition from foster care and child safety residential placements’ as their reason for seeking support from SHS.

Not all these clients required or received services relating to child protection from SHS agencies; they may have received other services (and must have received at least one service to be included in the study cohort).

A comparison cohort (non-CPO cohort) was also created, defined as clients aged 17 and under who received support in 2014–17 but who were not recorded as being on a CPO or as having ‘transition from foster care and child safety residential placements’ as a reason for seeking support from SHS. Some of these clients may have received services relating to child protection from SHS agencies, even though they were not on a care and protection order when presenting for service and did not specify transition from out-of-home care as a reason for seeking services.

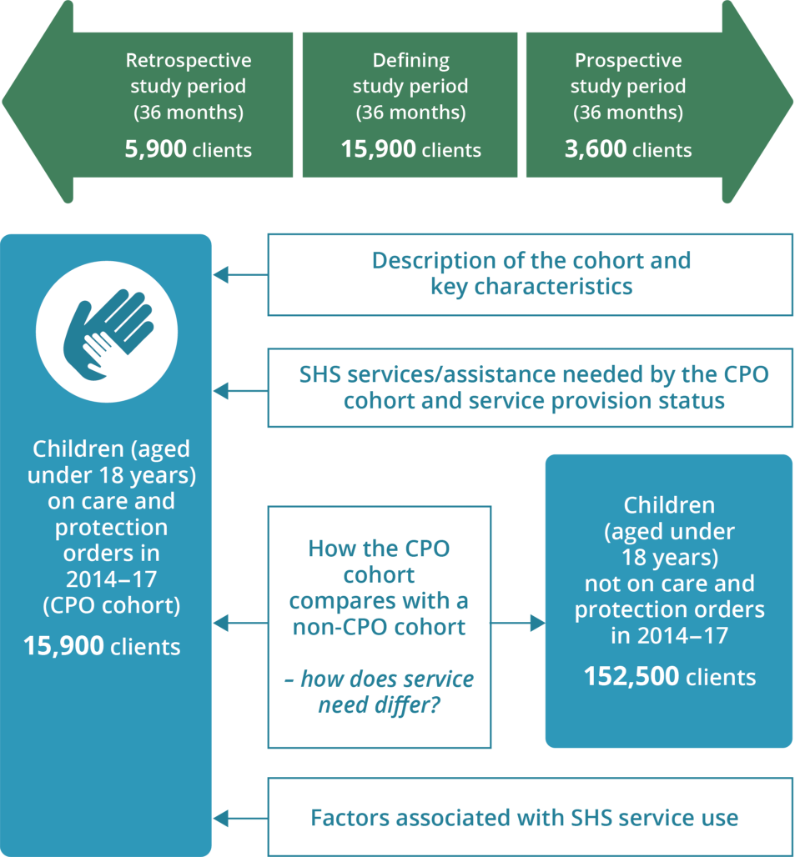

The longitudinal SHS data for the period 2011–12 to 2020–21 were used to examine characteristics and service use patterns of CPO clients and compare them with a non-CPO cohort (Figure CPO.1).

The retrospective study period for this cohort is the 36 months before the start of the defining study period (that is, the 36 months before the start of their first CPO-related support period in 2014–17). The prospective study period is the 36 months after the end of each client’s 36 month defining study period.

Key characteristics of the CPO cohort

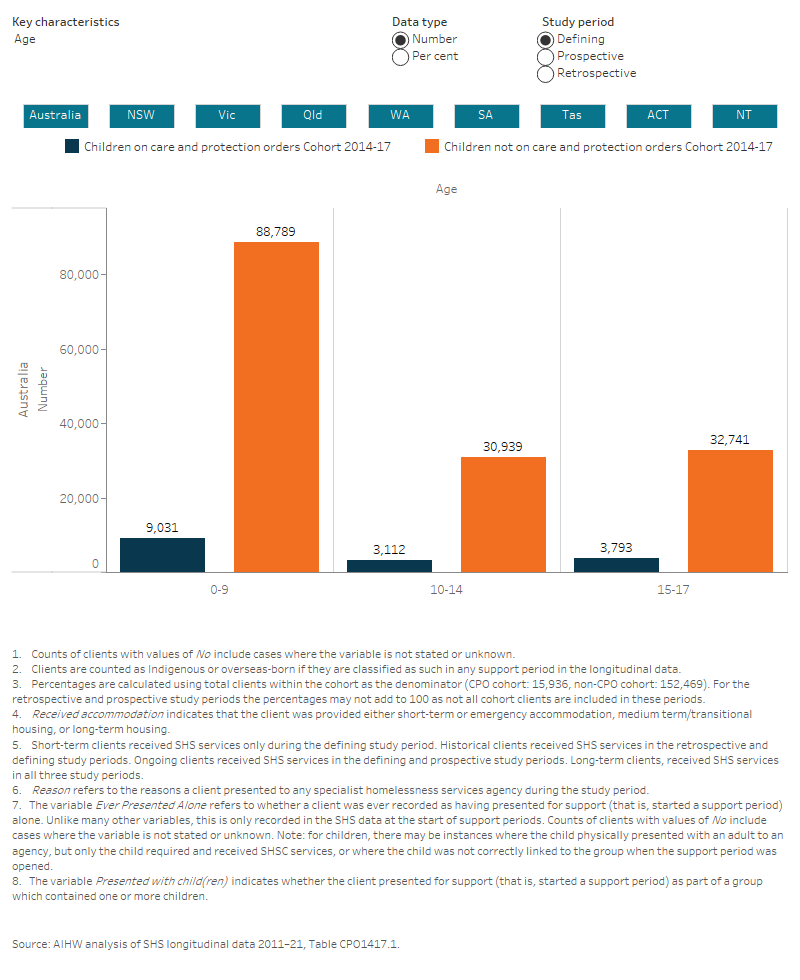

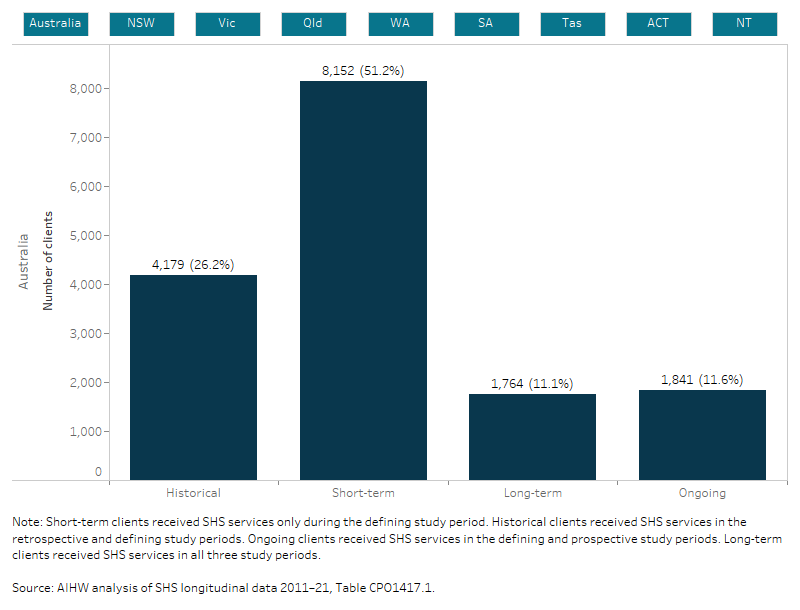

There were nearly 16,000 clients in the CPO cohort; these clients had the following key characteristics (Figure CPO.2, Table CPO1417.1, Table CPO1417.2):

- 57% (9,000) of clients were aged 0 to 9 years.

- Half (50% or 8,000 clients) of the children had only one support period in 2014–17.

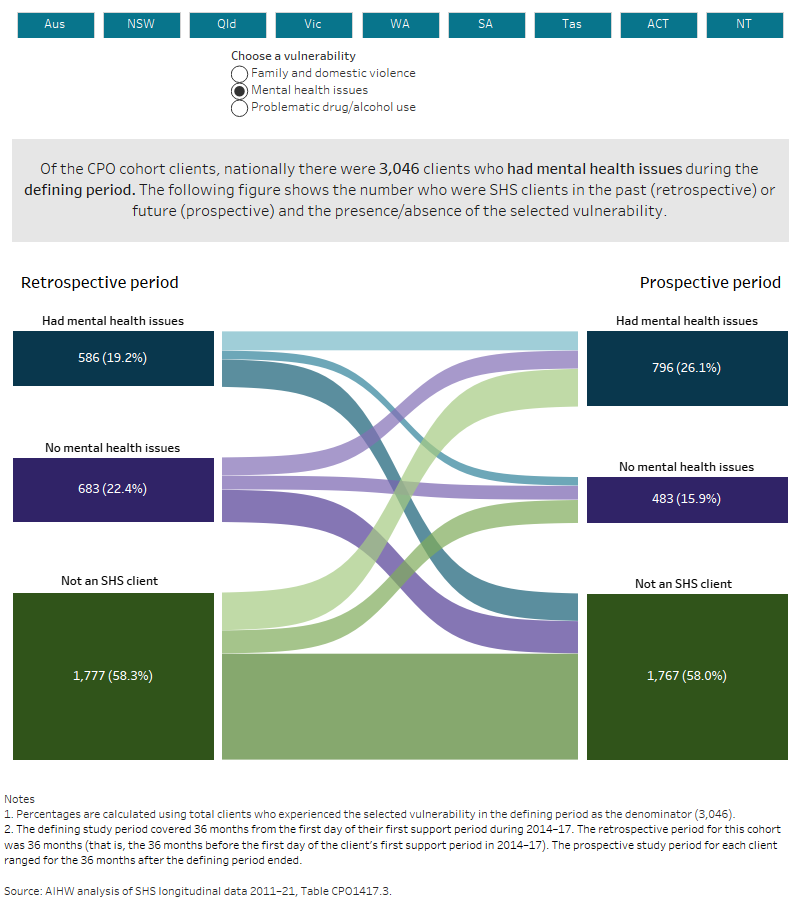

- Over half (53% or 8,400 clients) had experienced family and domestic violence in the defining period and 12% (1,900) had experienced family and domestic and had mental health issues in the defining period.

- One-third (31% or 4,900 clients) presented for support alone in the defining period (2014–17).

- Over two-thirds (67% or 10,700 clients) were known to have experienced homelessness at least once during their SHS support in 2014–17. Over one-third had been a couch surfer (36% or 5,800 clients) in the defining period with most of these clients (3,300) having experienced FDV.

- Housing crises and family and domestic violence were among the most common main reasons for seeking support.

Note: Children are included in the CPO cohort if they were on a care and protection order either the week before or at the time of presenting to an agency for specialist homelessness services. Other characteristics, such as their vulnerability flags or whether they were homeless or not, are aggregated over the entire defining study period and may not have occurred at the same time the child was on the care and protection order.