Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-clients-exiting-custodial-arrangements

MLA

Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 22 November 2022, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-clients-exiting-custodial-arrangements

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17 [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-clients-exiting-custodial-arrangements

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2022, Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-clients-exiting-custodial-arrangements

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

PDF | 1.2Mb

On this page:

Study cohort – Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17

Introduction

People exiting institutions and care into homelessness are a national priority homelessness cohort identified in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement which came into effect on 1 July 2018 (CFFR 2018).

Longitudinal analyses have been undertaken for a cohort of clients aged 10 and over who exited or transitioned from custodial arrangements throughout 2014–17, that is, SHS clients who:

- were referred to the agency from a youth or juvenile justice detention centre or adult correctional facility or

- transition from custodial arrangements was a reason for seeking assistance or

- the client’s residency in either the week before or at the time of presentation to an SHS agency was adult correctional facility, youth/juvenile justice detention centre or immigration detention centre.

Some of these clients were still in custody at the time they began receiving support. Note, in the SHSC, it is not possible to distinguish between clients who have received assistance without leaving an institutional setting (non-housing related support) and those who may have left an institutional setting but returned prior to the end of support.

Children aged under 10 cannot be charged with a criminal offence in Australia. Therefore, clients aged under 10 have been excluded.

These analyses examine SHS service patterns for a cohort of clients that can be tracked for a similar period in the past and into the future.

See Introduction to the SHS longitudinal data for details on the longitudinal analyses undertaken.

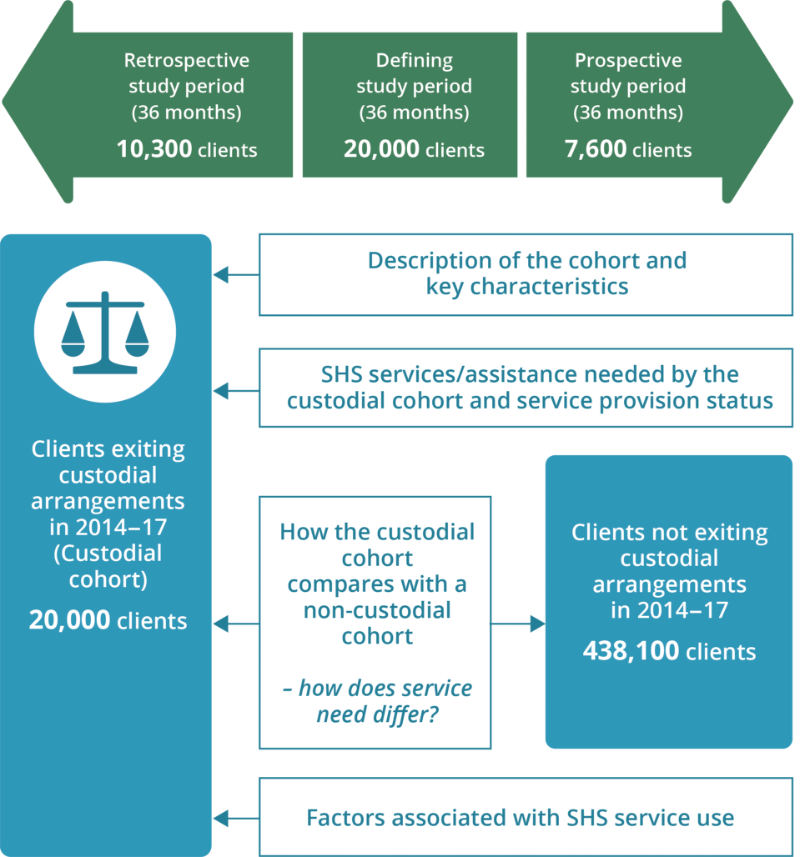

A non-custodial cohort was also created, comprising clients that received services sometime in 2014–17 but were not – while receiving services – either referred-from or resident-in a correctional facility and did not mark transition from a correctional facility as a reason for seeking SHS support. The longitudinal SHS data for the period 2011–12 to 2020–21 were used to examine characteristics and service use patterns of custodial cohort clients compared with the comparison cohort (the non-custodial cohort) (Figure Custody.1).

The comparison cohort allows for analyses that compare clients exiting custody compared with clients who also engage with SHS services but lack this defining feature. It does not offer any insights into the general population or people experiencing either time in custody or homelessness who do not receive SHS support.

The retrospective study period for this cohort is the 36 months before the start of the defining study period (which is the 36 months from the start of their first support period in 2014 to 2017). The prospective study period is the 36 months after the end of each client’s 36 month defining study period.

Figure Custody.1: Custodial cohort 2014–17, longitudinal analysis overview

Source: AIHW analysis of SHS longitudinal data 2011–21, Table Cus1417.1.

Key characteristics of the custodial cohort

There were nearly 20,000 clients in the custodial cohort; these clients had the following key characteristics (Figure Custody.2, Table Cus1417.1, Table Cus1417.2):

- Nearly 60% (11,600) of custodial cohort clients were aged 25 to 44 years and three-quarters were male.

- Nearly 6,000 clients (30%) were Indigenous.

- Only 10% (2,000 clients) presented for support with children sometime in the defining study period (that is, they received SHS support sometime in 2014–17 and had one or more children with them at the time of receiving any of the periods of support).

- Over half (57% or 11,500) needed long-term accommodation in the defining period, and 6.5% of those (740 clients) received that accommodation. Of these clients who received long-term accommodation in the defining period (Table Cus1417.2), 250 clients reported that they had been homeless in the prospective period and 160 clients received short-term accommodation in the prospective period, possibly indicating that ongoing support may also be required in addition to stable housing.

- One-third (6,700 clients) had only one support period during the defining study period and 48% (9,600 clients) had 3 or more support periods.

- Around half (51%) had received SHS support previously; that is, 10,300 clients had received SHS support in the 36-month retrospective period that preceded the defining study period.

- Around 38% of clients (7,600) continued to receive SHS support into the future; that is, they received support in the 36 months after the defining study period.

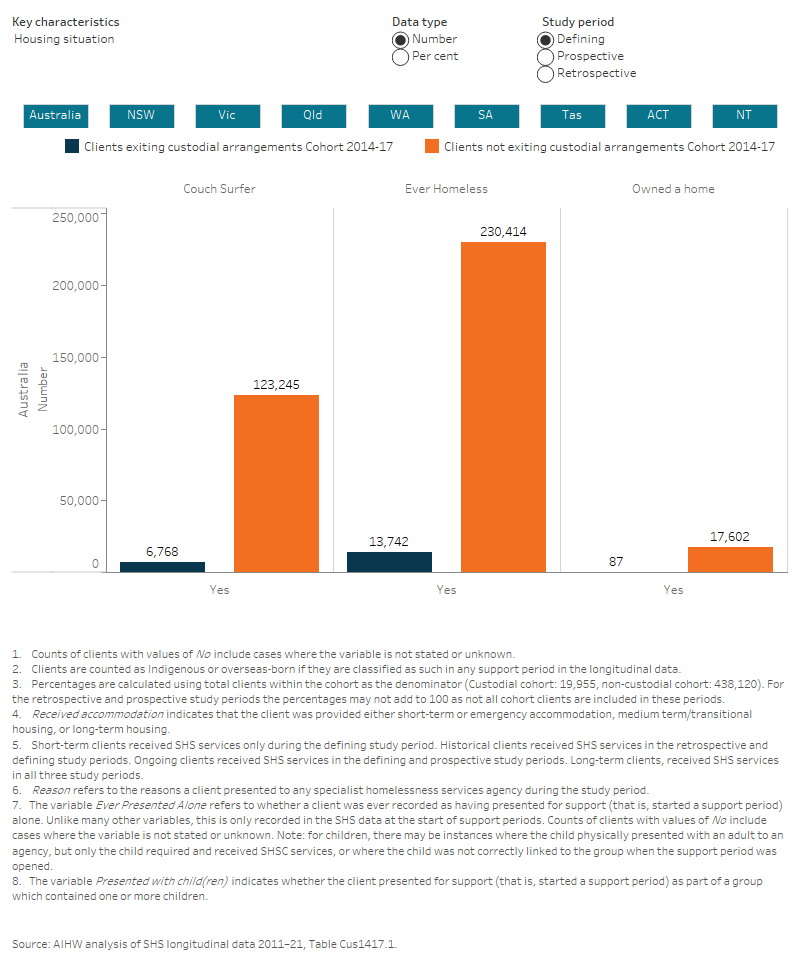

Figure Custody.2: Custodial and non-custodial cohorts 2014–17, client key characteristics, by study period

This interactive bar chart shows a comparison between the custodial and non-custodial cohorts, in terms of key characteristics and across all study periods (defining, retrospective and prospective). A radio button allows selection for the individual state/territory and Australia. For Australia, custodial clients were more likely to be male (custodial clients 75% compared with 36% non-custodial clients) and more likely to have problematic drug or alcohol issues (42% compared with 12%) and mental health issues (54% compared with 35%). They were less likely to be short-term clients (36% compared with 66%), meaning they were more likely to have received support in either the 36-month retrospective period (52% compared with 21%), the prospective period (38% compared with 22%) or both (26% compared with 9%).

Service engagement profiles

SHS support patterns of the custodial cohort over the entire longitudinal period (2011–21) were examined. Around a third (7,200 or 36%) of the cohort were short-term clients receiving services only during the 36-month defining study period; this was considerably lower than non-custodial clients (66%) (Figure Custody.3, Table Cus1417.1).

Over a quarter (26% or 5,100) were long-term clients, receiving support in all study periods and another 26% (5,100) were historical clients who were supported in the retrospective and defining periods. This is in line with literature that suggests a continued cycle of imprisonment and homelessness with ex-prisoners experiencing homelessness at 1.5 times the rate of others (Martin et al. 2021) and one-third of all people entering prison do so from a situation of homelessness (AIHW 2019). Only 9% of non-custodial clients were long-term clients.

Figure Custody.3: Custodial cohort 2014–17, service engagement profiles

This interactive bar chart shows service use patterns of the 2014–17 Custodial cohort over the entire longitudinal period (2011–21). Support information was combined from the discrete study periods into four service engagement profile groups (historical, short-term, long-term and ongoing). Engagement profiles for all states and territories and Australia can be selected and displayed. Nationally, of the 20,000 clients that made up the defining period cohort, 7,200 (36%) were short-term clients who only received support during the 12-month defining study period and 5,100 (26%) were long-term clients and had received support at various times over the 10-year period.

Vulnerability pathways

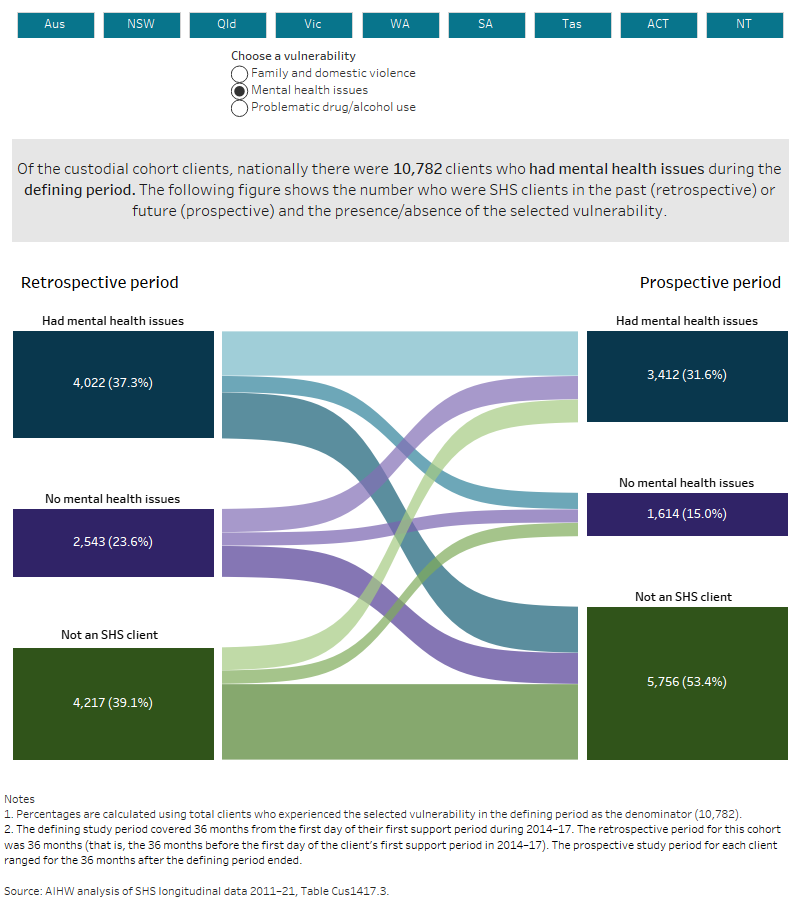

Using data for the entire longitudinal period, client profiles were examined for the presence of vulnerabilities including mental health issues, drug and/or alcohol problems, and experience of family and domestic violence (FDV) within each of the 3 study periods – the retrospective, defining and prospective periods (Figure Custody.4, Table Cus1417.1, Table Cus1417.3). For more information on the derivation of these vulnerabilities, see Methodology.

Over half (54%) of custodial cohort clients (10,800) had a current mental health issue in the defining period. Of these, 1,700 clients received SHS support and had mental health issues in both the retrospective and prospective periods. Over a quarter (26% or 2,900 clients) of clients with mental health issues in the defining period were not SHS clients in the retrospective and prospective periods.

Under half (42%) of custodial cohort clients (8,300) had an issue with problematic drugs/alcohol use in the defining period. Of these clients, over a quarter (26% or 2,200 clients) were not SHS clients in the retrospective and prospective periods. Of clients with problematic drugs/alcohol use in the defining period, 910 clients (11%) received SHS support and had problematic drugs/alcohol use in both the retrospective and prospective periods.

Figure Custody.4 shows vulnerability profiles for custodial clients, that is, the proportions experiencing FDV, with a current mental health issue and those with problematic drugs/alcohol use.

Figure Custody.4: Custodial cohort 2014–17, vulnerability pathways

This interactive Sankey diagram shows the 2014–17 Custodial cohort clients who experienced three vulnerabilities, clients who had experienced FDV, clients with a mental health issue and those with problems with drugs or alcohol in the defining study period and whether clients also experienced these vulnerabilities in the past and future study periods. These vulnerability pathways are shown separately, using radio buttons to select between vulnerability types. Using data for the entire longitudinal period, SHS Custodial cohort clients were assessed for the presence of these vulnerabilities within each of the three study periods – the retrospective, defining and prospective periods. Vulnerability data and pathways for all states and territories and Australia can be selected and displayed. Most clients at the national level only experienced the vulnerability in the defining study period and were not SHS clients in the retrospective and prospective study periods. The second largest category were clients who had experienced the vulnerability in all three periods (past, defining and future).

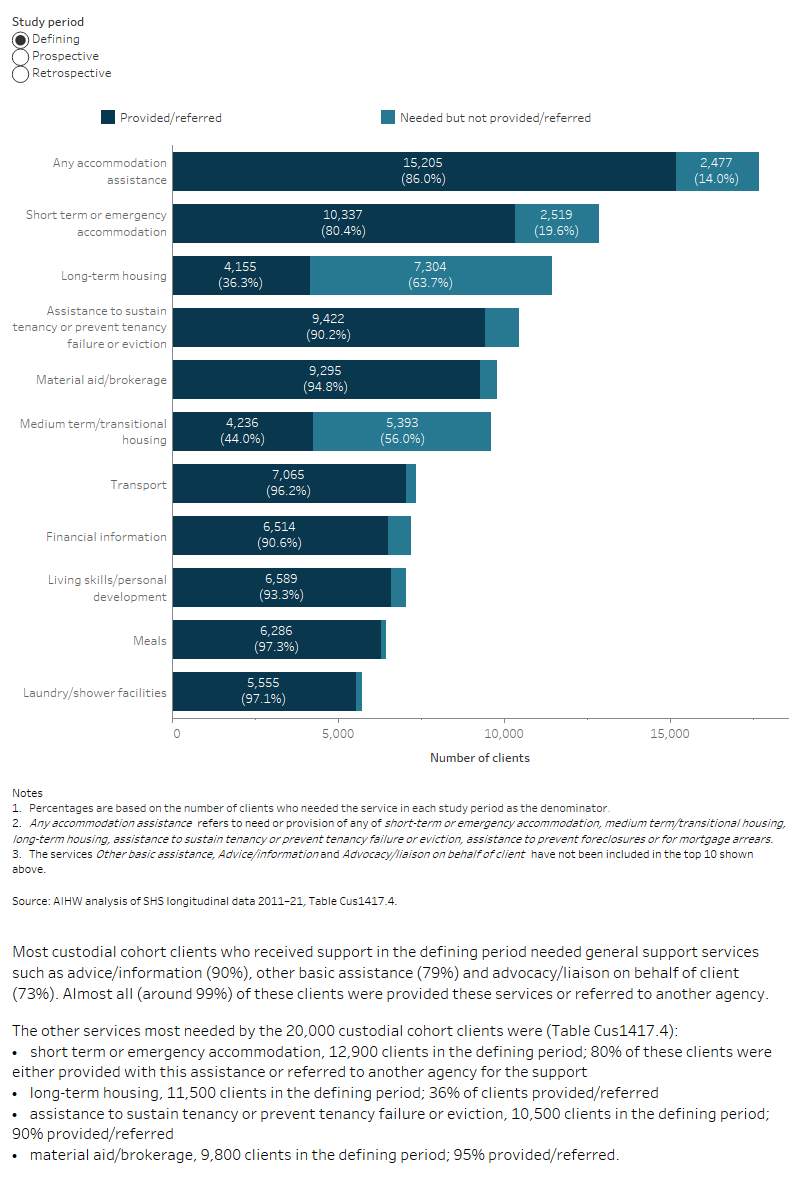

SHS services needed by custodial cohort clients

The need for accommodation assistance was common among custodial clients in all 3 time periods; 87-89% of clients required some form of accommodation assistance and between 84% and 89% received it (depending on the study period). This was most commonly short-term/emergency accommodation, needed by about 64% of clients and received by between 78% to 85% of those clients depending on the study period (Figure Custody.5 Table Cus1417.1, Table Cus1417.4).

Figure Custody.5: Custodial cohort 2014–17, select top 10 services and assistance needed and service provision status by study period

The interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the select top 10 services needed and the provision/referral status for the 2014–17 Custodial cohort clients (20,000 clients) who received support in the retrospective, defining and prospective study periods. Across all study periods, short-term or emergency accommodation was one of the most needed services, around 80% of these clients were either provided this service or referred to another agency. Material aid/brokerage was also a key service needed by this cohort; this service was provided/referred to over 90% of clients.

How the custodial cohort compares with a non-custodial cohort

In 2014–17, compared with the non-custodial cohort, custodial clients were (Figure Custody.2, Table Cus1417.1):

- more likely to be male (custodial clients 75% compared with 36% non-custodial clients)

- more likely to have problematic drug or alcohol issues (42% compared with 12%) and mental health issues (54% compared with 35%)

- more likely to have been homeless (69% compared with 53%) and to have received accommodation support (51% compared with 31%)

- more likely to be Indigenous (30% compared with 21%)

- less likely to be short-term clients (36% compared with 66%), meaning they were more likely to have received support in either the 36-month retrospective period (52% compared with 21%), the prospective period (38% compared with 22%) or both (26% compared with 9%).

How did service needs differ?

Differences in identified service need between custodial and non-custodial clients were examined using relative risk, calculated by dividing the risk of an event occurring for one group (specifically, service need for each service type separately for custodial clients) by the risk of an event occurring for another group (service need for non-custodial clients).

Custodial clients were 3.6 times more likely to need drug or alcohol counselling (relative risk (RR) 3.59) during the 2014–17 defining study period than non-custodial clients (Figure Custody.6; Table Cus1417.5).

Custodial clients often have limited housing options, many spend time in temporary or transitional accommodation as they face barriers to accessing social or private rental housing (Martin et al. 2021). Figure Custody.6 shows that in the defining period, custodial clients were more likely than non-custodial clients to need medium term/transitional housing (1.6 times), short-term or emergency accommodation (1.5 times) or long-term housing (1.4 times).

Custodial clients were 1.5 times more likely to need assertive outreach for rough sleepers and 1.4 times more likely to need medium term/transitional housing then non-custodial clients in the prospective period.

Custodial clients who received SHS support in the future (that is, in the 3 years after the defining study period) were 1.6 times more likely than non-custodial clients (in 2014–17) to use psychiatric services, 1.4 times more likely to need medium-term or transitional housing, and 1.3 times more likely to require short-term or emergency accommodation.

Figure Custody.6: Relative risk of needing a SHS service type, custodial and non-custodial cohort, by study period, 2014–17

The interactive risk ratio plot shows the differences in service need between custodial and non-custodial clients receiving SHS support in each study period, these associations are presented as relative risks. The top 6 services more likely to be needed by custodial cohort clients compared with non- custodial clients (that is, those with the largest relative risk) have been shown in the figure. A radio button allows selection of the services and relative risks for each of the study periods (defining, retrospective and prospective). Custodial clients were 4 times more likely to need drug or alcohol counselling (relative risk [RR] 3.59) during the 2014–17 defining study period than clients in the non-custodial cohort. Compared to non-custodial clients, custodial clients had much less need for interpreter services or assistance with immigration.

Factors associated with SHS service use

Descriptive regression models were used to examine whether client characteristics or support experience in the defining period were associated with SHS support in the prospective study period (ongoing service use). Information on interpreting regression models can be found in the section Understanding factors associated with past and future support. Two models were created; a ‘client characteristic’ model (Model 1) that contained client characteristics and a ‘reasons’ model (Model 2) that supplemented these characteristics with flags for the 26 possible reasons why the client sought support during the defining study period.

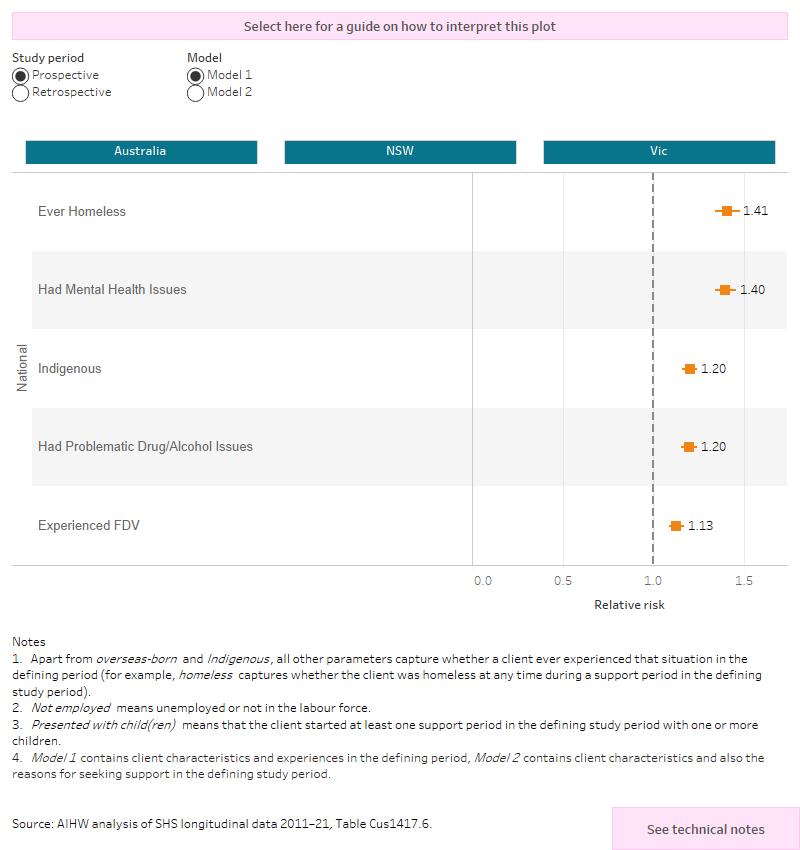

Variations in state and territory specific policies and service delivery models mean that the likelihood of a client receiving services in the future varies among states and territories. Therefore, in addition to a national model, separate regression models were created for each state or territory where there was sufficient sample size (at least 3,500 clients; Figure Custody.7). The models are descriptive, that is, they are intended to describe the client variables that are associated with past or future service use without proposing or testing specific causal pathways.

The outcome variable (receipt of SHS support) was a binary measure (yes or no) and did not distinguish between clients that needed SHS services only once in the prospective study period and clients that required frequent support.

Risk ratios were created to measure the association between the use of SHS services and a set of client characteristics (see Glossary entry on Relative risk for how to interpret the results)

Some bias is present in this outcome measure because some clients who required services in the future may not have been able to receive them (see the section on Bias within the SHSC longitudinal data).

The results from the client characteristic model (Model 1) demonstrates that clients who were homeless at any time in the defining period had the highest likelihood of receiving SHS services in the prospective period (41% higher). Mental health issues (40%) were also associated with future service use. Being an Indigenous Australian was also associated with a future service use (20% greater likelihood). This is partly due to the social and economic disadvantages faced by Indigenous Australians and a higher prevalence of health risk factors (POA 2004, AIHW 2020).

The reasons model (Model 2) demonstrates that clients that had housing crisis or transition from custodial arrangements as reasons for seeking support had the highest likelihood of using SHS services in the prospective period (27% and 25% higher, respectively). Clients with inadequate or inappropriate dwelling (18%) as a reason for seeking assistance were also associated with ongoing SHS support.

Figure Custody.7: Relative risk for use of SHS services (custodial cohort 2014–17)

The interactive risk ratio plot shows the characteristics or reasons for presenting that are associated with the custodial cohort clients’ use of SHS services in the past (retrospective) or future (prospective period), these associations are presented as relative risks. Relative risks for all states and territories and Australia can be selected and displayed. Two regression models can be selected, Model 1 contains client characteristics and experiences in the defining period, Model 2 contains client characteristics and the reasons for seeking support in the defining study period. For both past and future SHS support the associations were similar. Nationally, being homeless or experiencing mental health issues at some time during the defining study period or selecting housing crisis or transition from custodial arrangements as reasons for seeking support had the strongest association with past or future SHS support.

Summary

A cohort of nearly 20,000 SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17 were analysed. Compared with clients not exiting custody, these clients were much more likely to be male and have problematic drug or alcohol issues or mental health issues. They were also much more likely to have received SHS support in all 3 study periods, retrospective, defining and prospective (this support may not have been continuous). Clients exiting custodial arrangements who had experienced a housing crisis, transitioning from custody, mental health issues or were an Indigenous Australian had the highest likelihood of needing SHS support in the future.

AIHW (2019) The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Cat. no. PHE 246, AIHW, Canberra.

AIHW (2020) Health risk factors among Indigenous Australians. Australia's health 2020: snapshots. Australia’s health series no. 17 Cat. no. AUS 232. Canberra: AIHW.

CFFR (Council on Federal Financial Relations) (2018). National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Viewed 3 August 2022.

Martin C, Reeve R, McCausland R, Baldry E, Burton P, White R, Thomas S (2021) Exiting prison with complex support needs: the role of housing assistance, AHURI Final Report No. 361, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

POA (Parliament of Australia) (2004) A hand up not a hand out: Renewing the fight against poverty. Report on Poverty and Financial Hardship. Canberra: Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee.