< explore study cohort ARTICLES

Study cohort – Older clients in 2014–17

Homelessness amongst the older population is an increasing issue in Australia and as such older people are a priority homelessness cohort (see Older people).

Longitudinal analyses have been undertaken for a cohort of older clients (aged 55 years and over) that presented for specialist homelessness services. These analyses are designed to examine SHS service use patterns for a cohort of clients that can be tracked for a relatively similar period into the past and into the future.

See Introduction to the SHS longitudinal data for details on the longitudinal analyses undertaken.

The older cohort (older 2014–17) was defined according to the definition used in AIHW SHS publications such as the SHSC annual report (AIHW 2021). That is, SHS clients that were aged 55 and over in any of their support periods between July 2014 and June 2017 were included in the older 2014–17 cohort.

For these analyses, ‘older people’ have been defined as those aged 55 and over. People aged between 55 and 64 who have suffered homelessness, poverty and disadvantage over long periods of time may experience age related health conditions similar to those over the age of 65 (Dow et al. 2016). In addition, people aged 50 and over suffering job losses can find it difficult to re-enter the labour market due to age discrimination, health problems and family reasons (AHRC 2015). A growing number of mature aged unemployed people who are not yet eligible for the age pension are turning towards income support payments. Department of Social Services payment demographic data for June 2022 indicated that just under 30% of JobSeeker payment recipients were aged 55 and over, with 24% aged 55–64 years and 5% aged 65 and over (up from 22% receiving Newstart in June 2016 who were aged 55–64 years) (DSS 2022).

A comparison cohort (non-older cohort) was also created, comprising adult SHS clients aged between 18 and 54 years in all of their support periods in 2014–17.

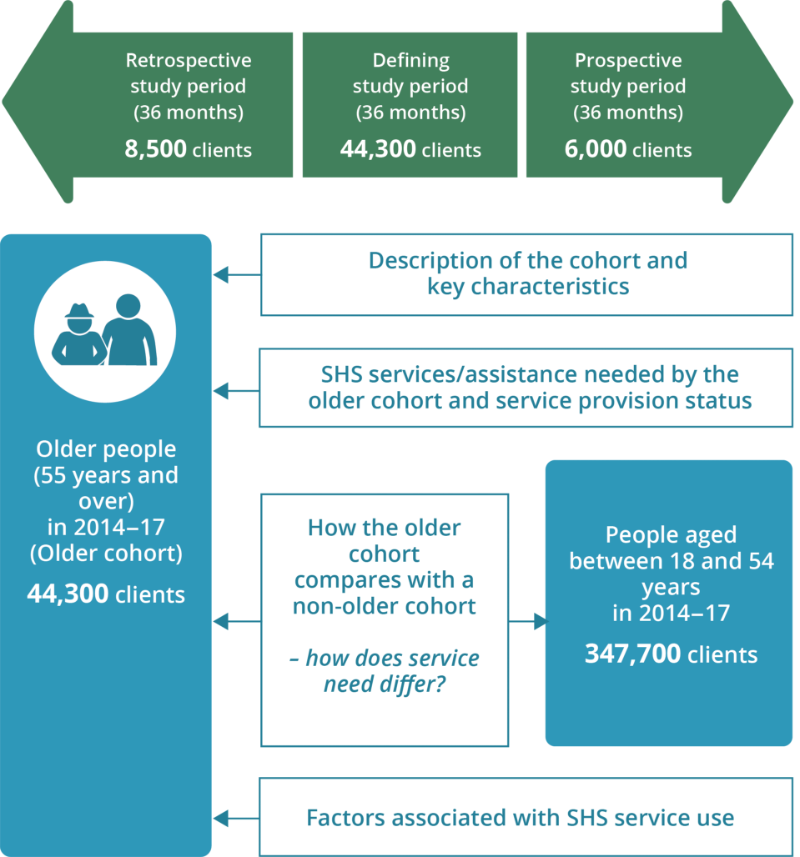

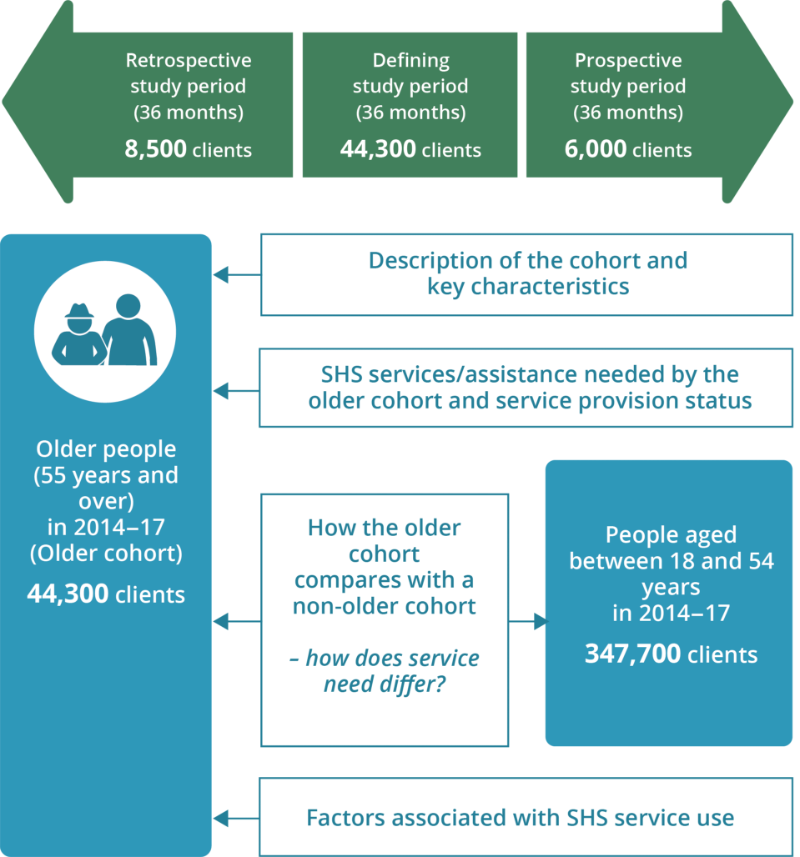

The longitudinal SHS data for the period 2011–12 to 2020–21 were used to examine characteristics and service use patterns of older clients (the older cohort) compared with the comparison cohort (the non-older cohort) (Figure Older.1).

The retrospective study period for this cohort is the 36 months before the start of the defining study period (which is the 36 months from the start of their first support period in which each client was aged 55 or over in July 2014 to June 2017). The prospective study period is the 36 months after the end of each client’s 36 month defining study period.

There were 44,300 clients in the older 2014–17 cohort; these clients had the following key characteristics (Figure Older.2, Table Older1417.1, Table Older1417.2):

- Two-thirds of older clients (66% or 29,300) were aged 55 to 64 years at the time of at least one of their support periods in 2014–17; the remaining 15,000 clients were 65 years or over.

- Over 57% were female (25,100 clients).

- Over half of clients (57%; 25,300 clients) had only one support period during the defining study period and 23% (10,200) had 3 or more support periods.

- A large proportion (91%) presented for support alone.

- Almost half (46%; 20,500 clients) sought support due to financial difficulties.

- Almost 40% (17,300 clients) were known to have experienced homelessness at least once during their SHS support in 2014–17; most of these clients (10,000) were male.

- Around 5,400 clients (12%) were Indigenous and 11,800 clients (27%) were overseas born.

- Around 19% had used SHS services previously; that is, 8,500 clients had received support in the 36-month retrospective period that preceded the defining study period.

- Around 13% of clients (6,000) continued to receive support into the future; that is, they received support in the 36 months after the defining study period.