Financial assistance

On this page

Quick facts

- At 28 June 2019, almost 1.29 million income units (individuals or group of related persons) received Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA).

- Of those receiving CRA, 2 in 5 (41% or 515,600 income units) were considered to be in rental stress after receiving CRA.

- If the income unit did not receive CRA, almost 7 in 10 (69% of 877,300 income units) would have been considered to be in rental stress.

- In 2018–19, 91,800 households received a type of Private Rent Assistance (PRA) from state and territory governments.

- A type of Home Purchase Assistance (HPA) was received by 42,500 households, and was more likely to be provided in major cities compared with Private Rental Assistance (72% and 62% respectively).

Financial assistance is a sizeable part of the broader provision of housing assistance in Australia. Governments provide various forms of financial support to assist people on lower incomes to meet housing costs, whether it is rental costs, mortgage repayments, saving a deposit for a home purchase or accessing finance. These housing costs are often a major expense for lower income earners and, therefore, financial assistance can be seen as an important safety net.

This section primarily focuses on the following three types of financial assistance:

- assistance with rental costs through the:

- Commonwealth Rent Assistance program

- Private Rent Assistance programs

- assistance with buying a home through Home Purchase Assistance programs.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA)

CRA is the most common form of housing assistance received by Australian households. It is an Australian Government payment to families and individuals who pay or are liable to pay private rent or community housing rent, over specified thresholds and are in receipt of:

- a social security or veterans’ income support payment; and/or

- receive Family Tax Benefit Part A at greater than the base rate.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance

CRA is a non-taxable payment, generally paid fortnightly to eligible recipients as part of a recipient’s primary payment rate. To be eligible, families or individuals paying private rent must: be in receipt of a social security or veterans’ income support payment and/or more than the base rate of Family Tax Benefit Part A, and pay or be liable to pay more than the specified rent thresholds.

CRA eligibility is based on eligibility for the primary payment and it forms part of the rate of payment. For information about CRA eligibility see Department of Social Services.

CRA is paid at 75 cents for every dollar above a minimum rental threshold until a maximum rate (or ceiling) is reached. The minimum threshold and maximum rates vary according to the household or family situation, including the number of children.

Certain social housing tenants are eligible for CRA, such as those living in community housing or Indigenous community housing and, in some states and territories, state owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH). CRA is not generally payable to public housing tenants as state and territory housing authorities already subsidise rent for these tenants.

Payment of CRA continues as long as recipients meet qualification and payability criteria for their primary payments, as well as CRA eligibility conditions.

Source: DSS 2019.

At 28 June 2019, around 1.29 million income units received CRA. This was around 25,200 income units fewer than in 2018 (or 2% less) and around 60,000 fewer than the peak of 1.35 million in 2016 (or 4% less) (Supplementary tables CRA.1) (AIHW 2017, 2018). The median CRA payment was $137 per fortnight, which was equivalent to 30% of median fortnightly rent ($460 per fortnight) (Supplementary table CRA.1).

In 2018–19, the Australian Government’s real expenditure on CRA was $4.4 billion, dropping from a peak of $4.6 billion in 2015–16 (SCRGSP 2020). Over time, most CRA payments were provided to income units in New South Wales (408,500 income units) followed by Queensland (330,300) (Supplementary table CRA.2).

At 28 June 2019, key characteristics of the income units receiving CRA include:

- Most were single with no dependent children (43%), followed by those who were single with one or more dependent children (21%).

- Most were in the age group 40 and over (62%), including 31% aged 60 and over.

- Around 1 in 5 received Newstart Allowance (20%), the Age Pension (22%) or a Disability Support Pension (20%) as their primary pension, allowance or benefit (Supplementary table CRA.2).

Location

For income units receiving CRA, the CRA payment (entitlement) received as a proportion of median fortnightly rent varied by location. In Sydney, an income unit’s CRA entitlement was 26% of rent (median fortnightly rent of $532.80), while in the rest of New South Wales, the CRA entitlement was a greater proportion of rental costs, at 34% (median fortnightly rent of $400.00) (Supplementary table CRA.1).

For Tasmania, the difference between CRA entitlements as a proportion of rent was smaller when comparing the capital city and rest of state. CRA entitlement was 31% of rent in Hobart and 34% in the rest of the state. This was similar for South Australia (31% and 35% respectively).

Rental stress

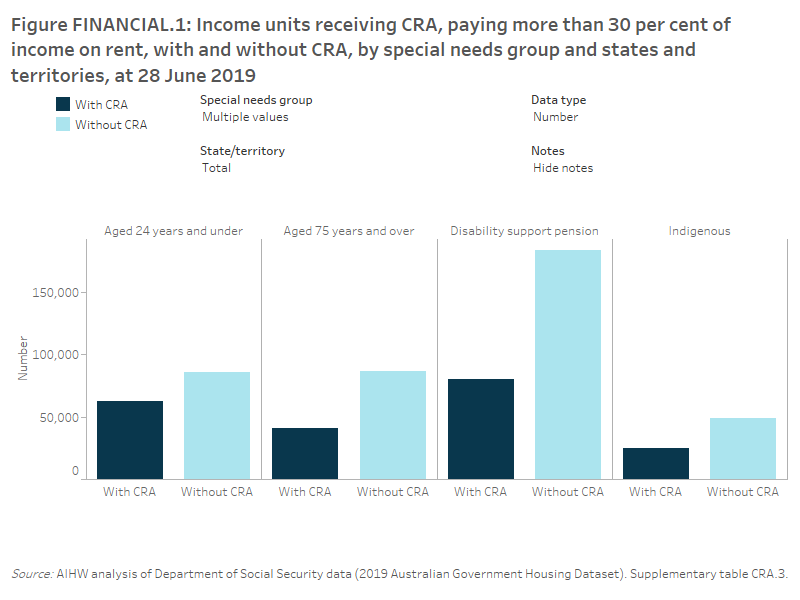

CRA has a considerable impact on improving rental affordability and reducing rental stress. Rental stress can be defined as spending more than 30% of gross household income on rent (SCRGSP 2020). At 28 June 2019, 69% of CRA recipients would have been in rental stress without CRA (Supplementary table CRA.3). However, with CRA, this proportion was lower, with 41% of CRA recipients in rental stress (Figure FINANCIAL.1).

Figure FINANCIAL.1: Income units receiving Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA), paying more than 30 per cent of income on rent, by special needs group and states and territories, at 28 June 2019. This vertical bar graph shows that for all income units nationally, 69% of those without CRA were considered to be in rental stress (paying more than 30% of income on rent) compared with income units receiving CRA where 41% were in rental stress, in 2019. Young people aged 24 years and under (58%) were the most likely of the special needs groups to be in rental stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of their income on rent) after CRA. With CRA, 28% of those aged 75 years and over were in rental stress. For income units without CRA, 79% of those aged 24 and under were in rental stress followed by 72% income units with an occupant receiving a Disability support pension. Across the states and territories, the highest proportion of income units in rental stress were those aged 24 years and under without CRA, ranging from 74% in Tasmania to 88% in ACT.

The impact of CRA on reducing rental stress varies between income unit types. In 2019, young people aged 24 years and under were the most likely of the special needs groups to be in rental stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of their income on rent) after CRA (58%) (Figure FINANCIAL.1; Supplementary table CRA.3). Without CRA, a much higher proportion of these young people (79%) would have been in rental stress. For those income units including at least one Indigenous member, 1 in 3 (33%) were in rental stress with CRA; without CRA, 2 in 3 (66%) would have been in rental stress. For income units with an occupant receiving the Disability support pension, 72% would have been in rental stress without CRA yet with CRA, considerably fewer (31%) were in rental stress.

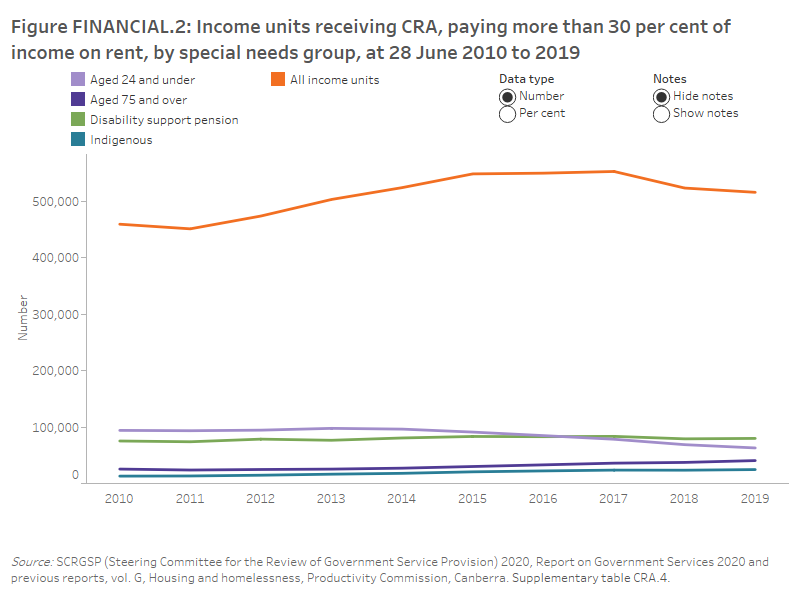

Rental stress for people aged 75 years and over receiving CRA was less likely, however the proportion of people aged 75 years and over in rental stress has been increasing (from 24% in 2013 to 28% in 2019). Rental stress was highest for income units aged 24 and under but remained steady between 2013 and 2019, at around 57% to 58% (Figure FINANCIAL.2; Supplementary table CRA.4).

Figure FINANCIAL.2: Income units receiving Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA), paying more than 30 per cent of income on rent, by special needs group, at 28 June 2010 to 2019. This line graph shows that rental stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of their income on rent) was highest for income units aged 24 and under receiving CRA. This remained steady at around 57% to 58%, between 2010 and 2019. The proportion of people aged 75 years and over in rental stress increased from 24% in 2013 to 28% in 2019. In 2019, 33% of income units including at least one Indigenous member and 31% of occupants receiving the Disability support pension were in rental stress.

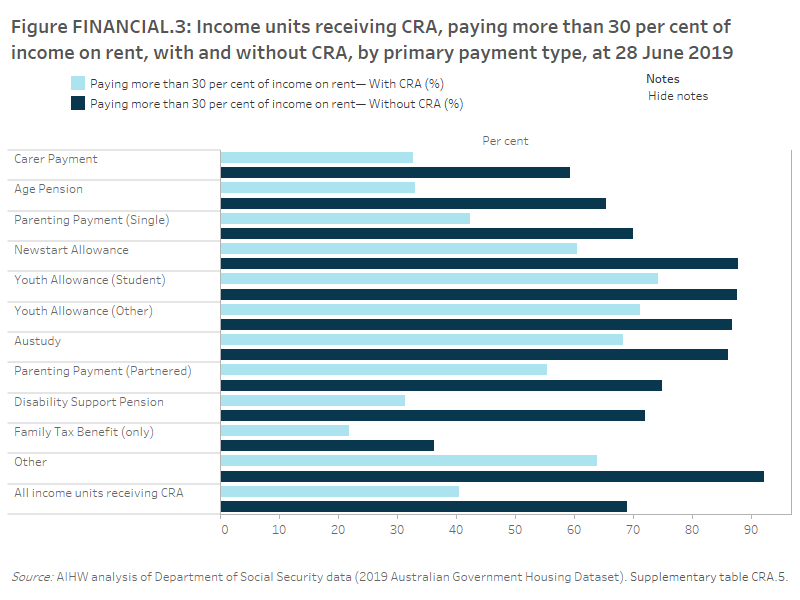

The incidence of rental stress between income units varied depending upon primary payment type and the receipt of CRA. In 2019:

- with CRA, 3 in 4 (74%) receiving Youth Allowance (Student) as their primary payment type were most likely to be in rental stress; without CRA, a higher proportion would have been in rental stress (88%) (Supplementary table CRA.5).

- with CRA, 1 in 3 (33%) receiving Age Pension as their primary payment type were in rental stress; without CRA 65% were in rental stress.

- with CRA, the majority of those receiving Disability support pension (69%), Age pension (67%) and Carer payment (67%) were not in rental stress (Figure FINANCIAL.3).

Figure FINANCIAL.3: Income units receiving Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA), paying more than 30 per cent of income on rent, with and without CRA, by primary payment type, at 28 June 2019. This horizontal bar graph shows that of the income units in rental stress receiving CRA, the highest proportion received Youth Allowance whereas of the income units without CRA the highest proportion in rental stress received Newstart Allowance. Of the income units receiving CRA, 74% of Youth Allowance (Student) recipients were in rental stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of their income on rent), followed by 71% of Youth Allowance (Other) recipients; 33% of Age Pension recipients were in rental stress. Of the income units without CRA, 88% of recipients receiving Newstart and Youth Allowance (Student) payments were in rental stress; 65% of Age Pension recipients were in rental stress.

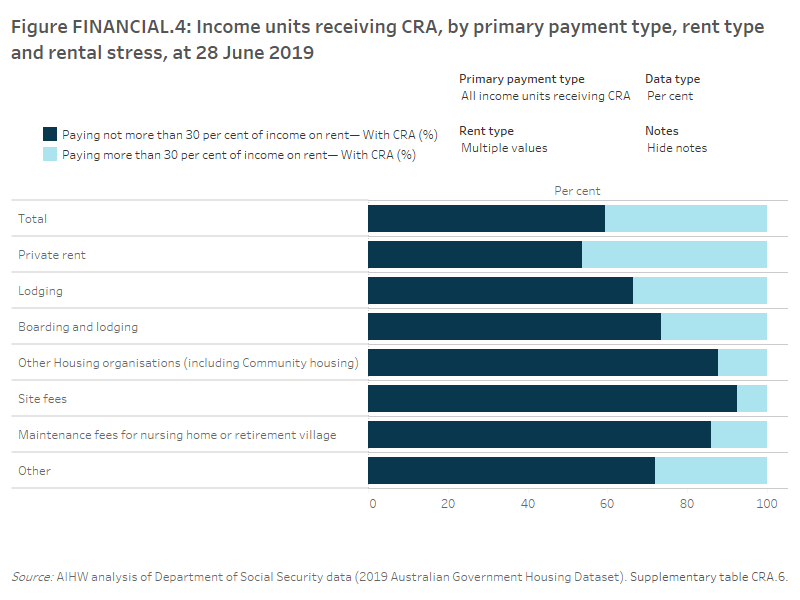

The experience of rental stress among income units receiving CRA was also different across primary payment and rent types. After receiving CRA:

- Those income units privately renting were most likely to be in rental stress (46% or 449,600 income units).

- Around 49,400 income units (30%) who were boarding and lodging in addition to lodging were also in rental stress (Supplementary table CRA.6).

- The vast majority of income units in other housing organisations, which includes community organisations, were not in rental stress (88% or 62,900 income units). These typically have capped rent (Figure 4).

Figure FINANCIAL.4: Income units receiving Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA), by primary payment type, rent type and rental stress, at 28 June 2019. This horizontal stacked bar graph shows for all income units receiving CRA, a higher proportion of income unit were not in rental stress (i.e. paying not more than 30% of income on rent) (60%) than those in rental stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of their income on rent) (41%). Income units who were renting privately (46%) had the highest proportion in rental stress, followed by recipients with the rent type lodging (34%). In contrast, 7.5% of recipients paying for site fees were in rental stress after receiving CRA and 12% of recipients living in other housing organisations (including Community housing).

Private Rent Assistance (PRA)

Private rent assistance is financial assistance provided directly by state and territory governments to low-income households experiencing difficulty in securing or maintaining private rental accommodation. PRA is usually provided as a one-off form of support such as bond loans and rental grants but can also include ongoing rental subsidies and payment of relocation expenses.

PRA may vary between states and territories and some products are not offered by all states and territories (e.g. rental grants are offered by New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania; relocation expenses are offered by Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory). For more information, see the Data quality statement for PRA.

In 2018–19, PRA was provided to 91,800 unique households; more unique households than in 2017–18 (88,300 households) (Supplementary table PRA.1). Households may receive more than one type of PRA and they may also receive multiple assistance payments for each type of PRA. There were around 118,400 total instances of PRA payments (Supplementary table PRA.3), with just over 117,500 households receiving the various types of PRA (Supplementary table PRA.2).

Consistent over time, bond loans (72,200 households) were the most common type of PRA in 2018–19, followed by one-off rental grants (32,900 households) (Supplementary table PRA.5).

Of the 91,800 unique households provided with PRA in 2018–19:

- The majority (73%) were households with the main applicant under 44 years of age; including 31% who were aged 25–34 years.

- 16% were Indigenous households.

- Other government pension/allowance was the main source of income for 80% of households, with a further 19% receiving employee income (Supplementary table PRA.4).

Location

The different states and territories provide different types of PRA. In 2018–19:

- Queensland (19,500 or 27%) and South Australia (16,400 or 23%) provided the greatest number of bond loans.

- South Australia provided half of the 32,900 one-off rental grants (16,400 or 50%).

- New South Wales provided ongoing rental subsidies to around 6,200 households (Supplementary table PRA.2).

In 2018–19, 3 in 5 (62%) PRA payments were to households located in Major cities, with a further 23% in Inner regional areas, 13% in Outer regional areas and around 1% in both Remote and Very remote areas (Supplementary table PRA.5).

Government assistance for home ownership

Over time, government policies and programs have focused on supporting Australians to achieve home ownership. Home ownership can be seen as providing greater security in retirement and a generally stable tenure type. Under current policy settings, the Australian Government’s assistance to homebuyers includes the:

-

First Home Loan Deposit (FHLD) Scheme: This scheme was introduced in 2020 and provides a guarantee for eligible first home buyers on low and middle incomes to purchase a home (up to maximum purchase price) with a deposit of as little as 5 per cent and without needing to pay for lenders mortgage insurance. The FHLD scheme has released 10,000 places this first financial year, and another 10,000 will be made available from July 2020. An eligible first home buyer’s home loan is available from participating lenders and up to 15 per cent of the value of the property purchased will be guaranteed by the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC).

This scheme can be used in conjunction with the First Home Super Saver Scheme or state and territory first homeowner grants and stamp duty concessions (NHFIC 2020).

-

First Home Super Saver (FHSS) Scheme: This scheme was introduced in the 2017–18 Federal Budget to reduce pressure on housing affordability. The FHSS scheme enables eligible people to save money for a first home using their superannuation fund arrangements (ATO 2019).

-

Indigenous Home Ownership Program: This scheme was introduced in 1975, and is available to help Indigenous customers buy their first home (IBA 2019).

-

First Home Owner Grant (FHOG): This scheme was introduced on 1 July 2000 and is a national scheme, which is funded and administered by the states and territories. The FHOG was made available to offset the effect of the GST on home ownership. Under the scheme, a one-off grant is payable to first homeowners that satisfy all the eligibility criteria (Australian Government 2020).

Some of these forms of assistance can be used in conjunction with one another and/or state and territory first homeowner grants and stamp duty concessions.

Home Purchase Assistance (HPA)

Home Purchase Assistance (HPA) is a form of government financial assistance administered by each state and territory. HPA includes a range of financial assistance for eligible households to improve their access to, and maintain, home ownership. HPA may vary from state to state and some products are not offered by all states and territories.

HPA can include:

- direct lending

- concessional loans

- mortgage relief

- interest rate assistance

- deposit assistance

- other assistance grants.

In 2018–19, the states and territories provided HPA to almost 42,500 unique households across Australia (Supplementary table HPA.1). There were around 43,000 households receiving any type of HPA, illustrating that households may be provided with more than one type of HPA (Supplementary table HPA.2).

The most common form of HPA was direct lending, with almost 37,600 households receiving this type in 2018–19. This has been stable over the last 5 years (Supplementary table HPA.2). There were fewer households provided with interest rate assistance, but the number has been steadily increasing; from 3,300 in 2013–14 to 4,000 in 2018–19.

Of the 42,500 unique households receiving HPA in 2018–19:

- Half (50%) of households assisted with home purchase had a main applicant aged 25–44 with a further 21% aged 45–54. One-quarter of households had a main applicant aged over 55 years (24%).

- One-quarter (24%) were households earning a gross income of less than $700 per week (or $36,400 per annum) (Supplementary table HPA.3).

Location

In 2018–19, HPA was predominantly provided in Western Australia (20,800 households or 49%) and South Australia (18,800 or 44%) (Supplementary table HPA.1). Direct lending was the main type of HPA assistance in these areas. South Australia also offered interest rate assistance (paid to 4,000 households).

In 2018–19, the majority of households that receive each type of HPA assistance were in Major cities (72%, or 31,000), followed by households in Outer regional areas (13%, or 5,800) and Inner regional areas (12%, or 5,000) (Supplementary table HPA.4). There were very few households that received each type of HPA assistance in either Remote (2%, or 1,000) or Very remote areas (less than 1%, or 200). Households may receive more than one type of assistance.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2017. Housing Assistance in Australia 2017. Cat. no. 189. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2018. Housing Assistance in Australia 2018. Cat. no. 296. Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO) 2019. First home super saver scheme. Canberra: ATO. Viewed 21 April February 2020

- DSS (Department of Social Services) 2019. Housing Support–Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Canberra: DSS. Viewed 13 February 2020

- Australian Government 2020. First Home Owner Grant. Viewed 21 April 2020.

- IBA (Indigenous Business Australia) 2019. Indigenous Home Ownership Program. Viewed 21 April 2020

- NHFIC (National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation) 2020. First Home Loan Deposit Scheme (FHLDS). Viewed 21 April 2020

- SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2020. Report on Government Services 2020–Housing and Homelessness sector overview data tables (Table GA.6). Viewed 13 February 2020