Legal systems

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

- The principal offence for the majority of defendants finalised for family and domestic violence criminal court cases in 2022–23 were either Acts intended to cause injury (49% or 49,400) or Breach of violence order (39% or 38,800).

- About 3 in 4 (78% or 78,300) defendants finalised for family and domestic violence offences in 2022–23 were found guilty.

- About half (47% or 133,000) of civil cases in the Magistrates’ Courts in 2022–23 involved a domestic violence order.

- The number of defendants finalised with a principal offence of Sexual assault and related offences has generally increased between 2010–11 to 2022–23.

Family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) causes immediate and long-lasting harm. The legal systems in Australia provide formal responses for people who experience FDSV (victim-survivors) that can prevent or reduce violence and punish those who have used violence. In this section, we highlight the available data on legal responses to FDSV.

How do victim-survivors interact with legal systems?

This page outlines aspects of legal systems that are specific to FDSV, such as the definitions of family and domestic violence (FDV) and sexual violence used in legislation across Australia, the legal responses available to prevent or respond to FDSV, and the legal assistance services available to help people engage with legal systems, see Table 1. Police are a key entry point to formal FDSV responses for many victim-survivors and people who use violence including those offered by legal systems. However, many victim-survivors of FDSV do not contact police, and not all cases reported to police are pursued further in legal systems (ABS 2009). For more information on FDSV and the police, see Family and domestic violence reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police.

Legal definitions of FDV and sexual violence

There is currently no uniform legal definition for FDV or sexual violence across federal and state and territory legislation, which includes family law, criminal law and other types of legislation (Table 1). Due to this, the legal responses to FDSV and to specific offences vary across states and territories. In cases where legal definitions of FDV are related to eligibility to receive a specialist FDV (or FV) service, differences in the definition of FDV can restrict access to support for victim-survivors in some jurisdictions (ALRC and NSW LRC 2010; SCSPLA 2021).

| Legislation related to FDSV | Legal responses to FDSV | Legal assistance services |

|---|---|---|

FDSV is defined in these federal, state and territory legislation. Federal

State/Territory

| Legal responses to FDSV describe the use of legal systems to enforce laws that can punish or prevent violence. Police enforce criminal law, can intervene in certain situations and can charge a person with a crime. This may result in a person going to court. Courts assess evidence and make judgements about how laws apply to situations, whether laws have been broken and what happens in response. They can include mainstream or specialist family and domestic violence courts. Specific responses related to FDSV:

| Legal assistance services help people who have experienced FDSV to engage with legal systems. Legal assistance services include:

For more information, visit the Attorney-General’s Department website. |

Note: The terms used to identify DVOs vary between states and territories, see Box 1.

Sources: AGD n.d.a; ALRC and NSW LRC 2010; SCSPLA 2017, 2021.

The types of abusive behaviours covered in each jurisdiction’s legislation not only differ but also can change over time to incorporate other forms of FDV such as economic abuse, technology-facilitated abuse, and coercive and controlling behaviours (refer to Coercive control, Intimate partner violence and Stalking and surveillance). Similarly, legal definitions of consent and sexual violence continue to evolve to better protect people from different forms of sexual violence (refer to Sexual violence and Consent).

The laws around child protection also vary across states and territories. The jurisdictions have responsibility for investigating and responding to child protection issues, including exposure to or experiences of domestic and family violence (National Legal Aid 2019b). For a discussion of data related to child protection, see Child protection.

Legal responses to FDSV

Legal responses to FDSV can involve civil and criminal proceedings of state and territory courts. On this page, proceeding refers to all the processes required to formally complete a case by a court:

- Civil proceedings can result in domestic violence orders (DVOs) that aim to protect victim-survivors of FDV from future violence.

- Criminal proceedings can punish people for criminal conduct related to FDV and sexual violence.

The terms used to refer to DVOs vary across jurisdictions (see Box 1). This report uses the term DVO to collectively refer to all terms used for DVOs nationally. In some states and territories temporary DVOs can be issued by police. If a DVO is breached, the matter can become a criminal offence. FDV that forms the basis for a DVO may also be the grounds for criminal proceedings (for example, physical and/or sexual assault). FDV that is not considered criminal under FDV legislation may still be used as the basis for DVOs (ALRC and NSW LRC 2010).

A Domestic Violence Order (DVO) is a civil order issued by a court that sets out specific conditions that must be obeyed and can include preventing a person from threatening, contacting, tracking or attempting to locate the protected person, and preventing a person from being within a certain distance of the protected person. The terms used to identify DVOs differ across jurisdictions:

- New South Wales – apprehended domestic violence order

- Victoria – family violence intervention order

- Queensland – domestic violence order

- Western Australia – family violence restraining order

- South Australia – intervention order

- Tasmania – family violence order

- Australian Capital Territory – family violence order

- Northern Territory – domestic violence order (Douglas and Ehler 2022).

Due to the National Domestic Violence Order Scheme all DVOs issued in states or territories from 25 November 2017 are automatically recognised and enforceable across Australia (AGD n.d.b). DVOs issued before 25 November 2017 can become nationally recognised by being ‘declared’ as a DVO recognised under the scheme at any local court (AGD n.d.b).

Most criminal and civil proceedings related to FDV are formally completed in the Magistrates’ Courts of each state and territory jurisdiction (see Box 2 for an explanation of court level groups). Criminal proceedings related to sexual violence are also often formally completed in Higher Courts (ABS 2024b; Productivity Commission 2024).

There is a hierarchy of courts within each state and territory with some variation in the levels of courts and names used in each jurisdiction (Productivity Commission 2024). Cases related to family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) can be heard in all levels of court. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Criminal Courts, Australia data collection groups the court levels used in each state and territory into three categories:

- Higher Courts – including Supreme Courts, District Courts and County Courts, which hear the most serious matters (including murder and the most serious sexual offences)

- The Magistrates’ Courts – including Magistrates Courts, Local Courts, Court of Summary Jurisdiction, and Court of Petty Sessions, which hear less serious offences, or conduct preliminary hearings

- Children’s Courts – Each state and territory has a Children’s Court, which hears offences alleged to have been committed by a child or juvenile (ABS 2024b).

Throughout this topic page these court level groups are used to simplify discussions of both state and territory civil and criminal courts.

The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, the Family Court of Western Australia and any specialist FDV courts are not included in the above court level groups and are discussed separately (ABS 2024b).

Restorative justice is an alternative response to FDSV whereby parties involved with a specific offence collectively resolve how to deal with an offence and its implications for the future (see Box 3).

There is still some debate around which practices can be considered restorative justice. Generally, restorative justice includes practices that involve the parties with a stake in a particular offence meeting to discuss and resolve the offence. In some cases, key participants do not meet face-to-face and instead exchange information by other means. The three most common practices are:

- victim–offender mediation, which can involve victims and offenders being given the opportunity to discuss their views with each other either face-to-face or indirectly, with active management and supervision by a mediation officer

- conferencing, which can involve people related to an offence including victims, offenders, victim or offender supporters, police officers and conference conveners coming together to discuss an offence and its impact

- circle and forum sentencing, which involves judges, lawyers, police officers, offenders, victims and community members coming together to determine an appropriate sentence for the offender (ALRC and NSW LRC 2010; Larsen 2014).

Restorative justice practices can be used at any stage in the criminal justice process, including at the time a person is charged, sentenced, and after they have served their sentence. Restorative justice practices are used throughout Australia with conferencing for young offenders used in all states and territories and some states and territories using restorative practices for adults (ALRC and NSW LRC 2010; Larsen 2014).

The evidence on the impact restorative justice has on reoffending suggests it is as good as traditional court sanctions. There is increasing evidence for other key benefits it may have, such as victim satisfaction, offender responsibility for actions and increased compliance with orders (Larsen 2014).

There are some limitations and challenges to the application of restorative justice in cases of FDSV as these offences often relate to power and control. For example, such cases can involve: perpetrators being unwilling to take personal responsibility and using the informal nature of restorative justice sessions to gain information about victims or assert ongoing forms of subtle control; victims with histories of trauma, ongoing fear and attachment to the perpetrator, which may result in greater difficulty advocating for themselves or increased pressure to reconcile with perpetrators; community members who are participating in the restorative justice process condoning violence due to societal tolerance of offences and negative gender norms (Jeffries et al. 2021).

FDSV can affect decisions related to family law. This includes cases where there are issues around the division of finances and/or property after separation, and/or issues with parenting orders (a set of orders about the parenting arrangements for a child). Some matters related to family law can be considered in the Magistrates’ courts. The most complex family law disputes, including those involving FDV, are considered in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, and the Family Court of Western Australia. The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia was formed by combining the previous Family Court of Australia with the Federal Circuit Court of Australia as of 1 September 2021 (FCFCOA 2023; SCSPLA 2017).

There are specialist FDV courts in locations around Australia (ALRC and NSW LRC 2010). These courts specialise in the handling of civil and/or criminal FDV matters. While the model for each court varies between jurisdictions, they generally use specialised case coordination mechanisms, integration with support and referral services, and special arrangements for victim-survivor safety (McGowan 2016). Evaluations of these specialist courts generally show advantages compared with mainstream courts, such as simpler navigation through legal systems, faster processing of cases and improved access to services for victim-survivors (McGowan 2016; ARTD consultants 2021).

Legal assistance services related to FDSV

General and tailored legal assistance services are available to advise and help people who have experienced or perpetrated family, domestic and sexual violence engage with legal systems (AGD n.d.a):

- Each state and territory has a Legal Aid Commission that provides services, including legal advice and representation in courts and tribunals for victim-survivors and perpetrators of FDSV (AGD n.d.a). Services are free of charge to people who meet means and merits tests set by each commission.

- Each Legal Aid commission has a Family Advocacy and Support Service that combines free legal advice and support at court for people affected by FDV (National Legal Aid 2019a).

- Specialist domestic violence units help women affected by FDV, who may otherwise be unable to access the support they need, with tailored legal assistance and other holistic support (AGD n.d.c).

- Through health justice partnerships, lawyers provide women affected by FDV with legal assistance in healthcare settings (AGD 2022).

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (ATSILS) provide culturally appropriate and safe legal assistance services to First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) victim-survivors and perpetrators of FDSV. The National ATSILS website provides links to State and Territory specific services (NATSILS 2022).

- The National Family Violence Prevention Legal Services program include First Nations community-controlled organisations throughout Australia who provide culturally safe legal services for First Nations people who experience FDV (NFVPLS 2022).

- Community legal centres are independent, community-managed, non-profit organisations offering free and accessible legal help to everyday people (CLCA 2019).

- Family Relationship Centres provide information about healthy family relationships, family dispute resolution mediation, advice around separation and referral to other specialist services (Family Relationships Online 2022).

In 2024, the ABS released experimental data about legal assistance clients and services for the first time (see Box 4).

The experimental national legal assistance services data represent clients and services funded through the National Legal Assistance Partnership Agreement (2020-2025) (NLAP), and completed between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023 by a Legal Aid Commission (LAC), Community Legal Centre (CLC) or an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service (ATSILS). Clients can be either the victim/applicant or the alleged perpetrator/respondent. The data do not differentiate between these client types.

Service data includes information about the ‘problem type’ – the legal matter(s) for which a client seeks legal assistance. This allows for reporting about legal assistance services provided for the family/domestic violence related matters ‘Domestic violence protection order’ (under civil law) and ‘Domestic/Family violence’ (under criminal law), and ‘Sexual assault and related offences’ (under criminal law). Where a single service involves more than one problem type, a ‘primary’ problem type is reported to indicate the problem considered to have had the most substantial impact on the client (as determined by the service provider).

In 2022–23, of legal assistance services completed:

- 6.3% (almost 47,500) were for domestic violence protection orders (civil law)

- 6.4% (almost 48,100) were for domestic/family violence (criminal law)

- 0.8% (around 5,700) were for sexual assault and related offences.

The experimental data should be interpreted with caution. In particular, the experimental family/domestic violence related problem type data are an underrepresentation of family/domestic violence related legal problems and inferences should not be made based on these data.

For more information, please see the Legal Assistance Services methodology on the ABS website.

Source: ABS 2024c.

Related formal responses and services

Apart from legal systems, there are a wide range of other services that work with victim–survivors, perpetrators and families in preventing and responding to FDSV. For more information, see Services responding to FDSV.

For example, perpetrator intervention programs aim to help people who use violence to stop using it. Court judgements can mandate individuals to attend perpetrator interventions as a part of legal proceedings (ANROWS 2021; Mackay et al. 2015).

For information related to specific services, see Specialist perpetrator interventions, Health services, Housing and Helplines and related support services.

What do we know?

DVOs are the most broadly used legal response to FDV (Taylor et al. 2015). Research suggests that DVOs can help as a deterrent through risk of punishment, through setting boundaries and reducing access to the victim-survivor, and by clearly defining the violence and its criminality (Dowling et al. 2018). There are, however, relatively few studies that assess the effectiveness of DVOs. Reviews of the available research found that DVOs:

- result in a small but significant reduction of re-victimisation

- are more effective for victim-survivors who are employed and/or in a higher socioeconomic group

- are less effective where perpetrators have histories of FDV and criminal offending, mental health issues, and they share children with the victim-survivor

- can improve victim’s and survivors’ perceptions of safety (Bell and Coates 2022; Dowling et al. 2018).

Research into how Australian legal systems respond to FDSV have identified some key issues, including:

- Misidentification of the victim–survivor as the perpetrator – this can occur when legal systems do not consider the wider context of violence and misinterprets the victim–survivor’s behaviour. For example, a victim–survivor may use violence in response to violence perpetrated against them and may appear agitated or ‘uncooperative’. These are normal responses to trauma and can be misinterpreted (Nancarrow et al. 2020).

- Adversarial environments – legal proceedings can expose victim–survivors to victim-blaming, unfair treatment and re-traumatisation. Historically, unsafe practices have also been used, such as shared waiting rooms and inappropriate lines of questioning (Deck et al. 2022; DSS 2022).

- Barriers to accessing legal services – access to legal systems can be limited due to many factors including: negative experiences with police and the judiciary; costs; the complexity of legal processes; concerns about giving evidence against family members due to shame, stigma, a fear of retaliation, or other reasons; and limitations in available legal services, culturally and linguistically appropriate services and coordination between legal and other services (DSS 2022).

- Legal system abuse – Legal systems can be misused by perpetrators of FDSV to further victimise people (see Box 5).

Research has shown that it is possible for legal systems to be manipulated by perpetrators of FDSV to threaten, harass and assert power and control over people (systems abuse). A perpetrator of FDSV may abuse legal systems through:

- misusing applications for DVOs to intimidate a person into withdrawing their DVO application (cross applications), or by misleading a victim-survivor into breaching a DVO

- using proceedings as an opportunity to continue harassment of someone and deny or minimise abuse

- interrupting, delaying or prolonging formal processes to increase a victim–survivor’s costs and disrupt their life

- engaging multiple lawyers in the same area to prevent someone from accessing legal representation on the basis of conflict of interest. This is a particular concern in regional, rural and remote communities (Douglas 2018; Douglas and Ehler 2022).

Systems abuse can adversely affect a victim–survivor’s health, wellbeing, finances and social connections. It can result in a victim-survivor being unprotected or falsely charged as a perpetrator and undermines legal systems. For more general information about systems abuse and how it relates to coercive control, see Coercive control.

Issues within legal systems have contributed to mistrust of the systems and are worsened by historical and ongoing discrimination and stereotyping experienced by parts of Australian society including First Nations people, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, LGBTIQA+ people, older people and people with disability (DSS 2022).

There are ongoing efforts to respond to these issues and combat systems abuse, such as the development of specialist courts that deal with FDV offences and sexual offences, tailored legal assistance services and legal system reforms. Future efforts towards improving legal systems are highlighted in the National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032; and The Meeting of Attorneys-General work plan to strengthen criminal justice responses to sexual assault 2022–2027 (DSS 2022; AGD 2022).

The 2 main national data sources used in this topic page are ABS Criminal Courts and the Report on Government Services – Courts. For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

What do the data tell us about legal systems?

Civil courts – Domestic violence orders

National data are available on applications for domestic violence orders (DVOs) through the Magistrates’ Courts. The data relate to finalised originating applications, which are new applications and exclude interim orders, applications for extension, revocations or variations. Civil non-appeal lodgements that have had no court action in the past 12 months are counted as finalised. While DVOs are generally dealt with at the Magistrates’ Court level, they can also be made at other court levels. National data are not currently available on the number of DVOs in effect (Productivity Commission 2024).

-

47%

Almost half (47% or 133,000) of civil cases in the Magistrates’ Courts in 2022–23 involved a domestic violence order

Report on Government Services - Courts

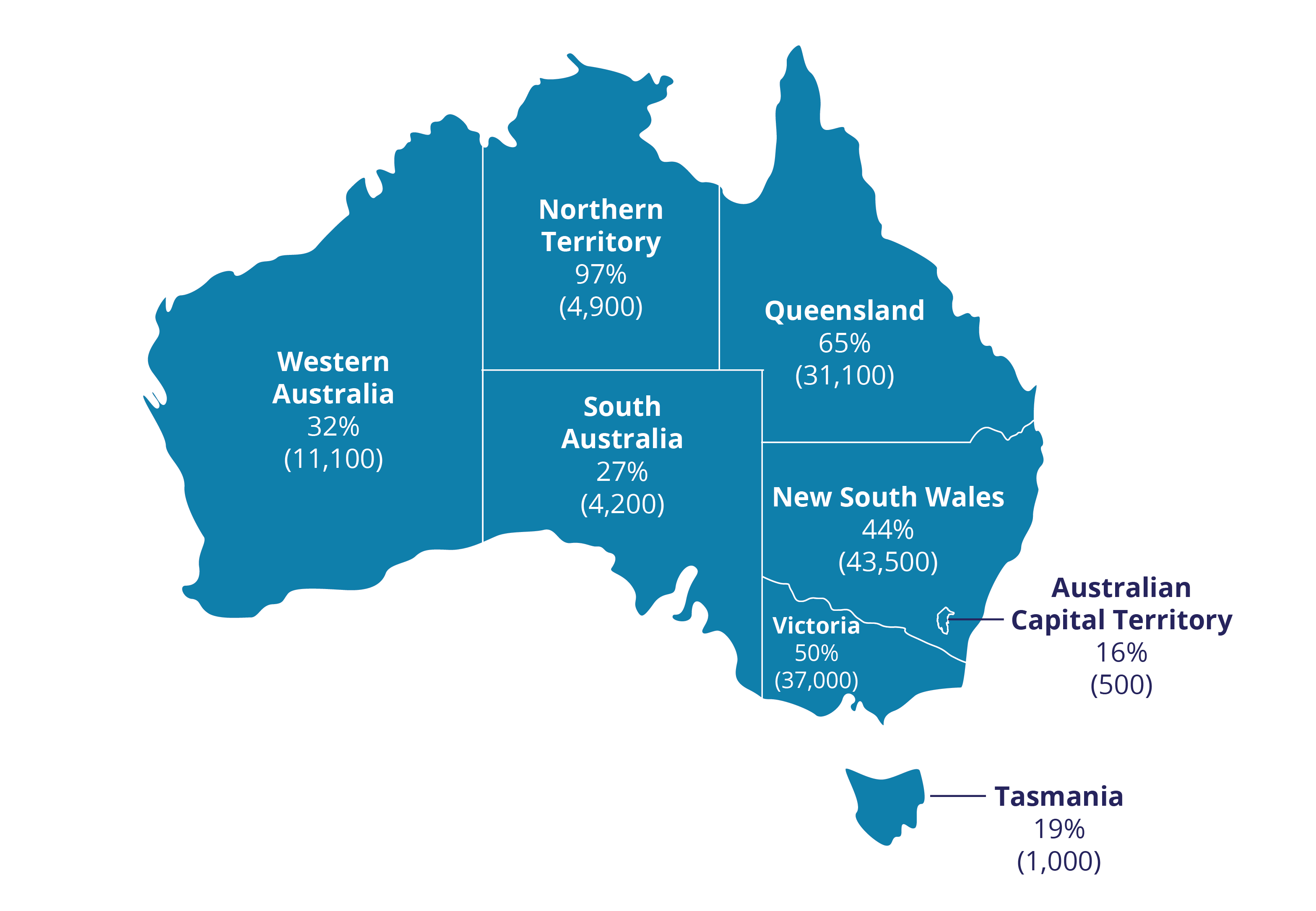

Almost half (47% or 133,000) of civil cases finalised in the Magistrates’ Courts in 2022–23 involved finalised originating applications for DVOs. The Northern Territory (97%) had the highest proportion of civil cases involving applications for DVOs and the Australian Capital Territory had the lowest (16%) (Productivity Commission 2024; Figure 1). Offences such as breaches of DVOs are dealt with by state and territory criminal courts (see Criminal courts).

Figure 1: Proportion of civil cases finalised in the Magistrates’ Courts that involved finalised originating applications for DVOs, by state or territory, 2022–23

Notes

- Finalised originating applications for DVOs include new applications and exclude interim orders, applications for extension, revocations or variations. Civil non-appeal lodgements that have had no court action in the past 12 months are counted as finalised.

- In Tasmania, police can issue Police Family Violence Orders (PFVOs) which are more numerous than court-issued orders. PFVOs are excluded from this table.

Source: Productivity Commission 2024.

Criminal courts

Data from the ABS Criminal Courts data collection (ABS criminal courts data) includes information on the characteristics of defendants dealt with by state and territory criminal courts, including case outcomes and sentences associated with those defendants. A defendant refers to a person against whom one or more criminal charges have been laid which are heard together as one unit of work by the court. ABS criminal courts data only relate to defendants and cases taken to court and do not include defendants from specialist FDV courts. There is a delay between when someone is charged and when their case reaches court (ABS 2024b).

On this topic page, we discuss defendants whose cases have been ‘finalised’, which means all charges relating to the one case have been formally completed (within the reference period). Unless otherwise stated, a ‘finalised’ defendant refers to a person whose charges have been finalised by methods other than ‘transfer to other court levels’. This is to reduce double-counting of defendants that are transferred then finalised again at a different court level. A defendant that is acquitted indicates that charges were not proven (see Data sources and technical notes) (ABS 2024a, 2024b).

ABS criminal courts data on family and domestic violence (FDV) defendants are considered experimental with further assessment required to ensure comparability and quality. Data on FDV defendants are limited to certain offence categories defined by the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC) including:

- Acts intended to cause injury (02) – Acts, excluding attempted murder and those resulting in death, which are intended to cause non-fatal injury or harm to another person and where there is no sexual or acquisitive element.

- Breach of violence order (1531) – An act or omission breaching the conditions of a violence order (referred to as a DVO in this topic page)

- Sexual assault and related offences (03) – Acts, or intent of acts, of a sexual nature against another person, which are non-consensual or where consent is proscribed (as in, the person is legally deemed incapable of giving consent because of youth, temporary/permanent (mental) incapacity or there is a familial relationship) (see Data sources and technical notes for a full list of offences) (ABS 2011; 2023a).

To address state and territory variation in the legislation and coding of harassment and stalking offences, from 2021–22 the ABS combined these data for output in the category Stalking, harassment and threatening behaviour. This combined category includes some ANZSOC offence codes that are also included in the categories Acts intended to cause injury and Abduction/harassment (ABS 2024b).

Predominantly this topic page discusses data related to the principal (most serious) offence category (see Data sources and technical notes). Data are also presented on all defendants with an FDV-related breach of violence order, regardless of whether it was the principal offence.

Some defendants finalised for Sexual assault and related offences may also be counted in the number of FDV defendants (ABS 2024a).

Family and domestic violence offences

-

3 in 4 defendants

finalised for family and domestic violence offences in 2022–23 were found guilty

Source: ABS Criminal Courts

About 99,900 defendants were ‘finalised’ for FDV offences in Australia in 2022–23 (FDV defendants). Of these:

- over 3 in 4 (78%, or about 78,300) were found guilty

- about 1 in 19 were acquitted (5.3%, or about 5,300)

- about 1 in 6 (16%, or about 16,100) were withdrawn by the prosecution (ABS 2024a).

The proportion of defendants finalised for FDV offences that were found guilty varied by state and territory, with the proportion about 70% or greater for all except Australian Capital Territory (62%) and South Australia (36%). The majority of defendants were finalised in the Magistrates’ Courts (94%, or about 94,000) (ABS 2024a).

The most serious offence for the majority of family and domestic violence court cases in 2022–23 was either Acts intended to cause injury (49% or 49,400) or Breach of violence order (39% or 38,800).

The most common principal offences among defendants finalised for FDV in 2022–23 were Acts intended to cause injury (49%, or 49,400), including 41,400 with a principal offence of Assault, and Breach of violence order (39%, or 38,800) (Figure 2; ABS 2024a).

Figure 2: The most common principal offence categories among FDV defendants, 2022–23

| Offence | Per cent |

|---|---|

| Acts intended to cause injury | 49.4% |

| Breach of violence order | 38.8% |

| Stalking, harassment and threatening behaviour | 9.9% |

| Property damage | 7.3% |

| Abduction/harassment | 2.1% |

| Sexual assault and related offences | 2.0% |

| Other dangerous or negligent acts | 0.3% |

| Homicide and related offences | 0.1% |

Notes:

- Components are not able to be added together to produce a total. Offence categories are not mutually exclusive and defendants may be counted in multiple categories.

- New South Wales legislation does not contain discrete offences of stalking, intimidation and harassment (as per ANZSOC categories), and so all such offences are coded to ANZSOC Group 0291 Stalking (in Division 2 Acts intended to cause injury). Therefore, Stalking offences may be overstated and Abduction/harassment may be understated.

- Stalking, harassment and threatening behaviour ANZSOC offences have been combined in the category Stalking, harassment and threatening behaviour. This includes offences also included in the categories Acts intended to cause injury and Abduction/harassment, see Box 5.

- Proportion represents the proportion of all defendants finalised for FDV offences (excluding transfer to other court levels).

- Number of defendants finalised for FDV offences by transfer to other court levels in 2022–23 was about 2,800 compared with 99,900 finalised by other methods.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ABS Criminal Courts

|

Data source overview

The offence Breach of violence order is often heard in cases involving ‘more serious’ FDV-related offences (for example assault), which usually become the principal FDV offence for the defendant (ABS 2024b). The total number of FDV defendants finalised for Breach of violence order, regardless of whether this was their principal FDV offence, was about 55,400 in 2022–23 (ABS 2024a).

The proportion of finalised FDV defendants found guilty in 2022–23 varied by principal FDV offence category with the highest proportion for Breach of violence order (91%) compared with Property damage (86%), Stalking, harassment and threatening behaviour (75%), Acts intended to cause injury (68%), Homicide and related offences (63%) and Sexual assault and related offences (57%) (ABS 2024a).

The most common principal sentences given to defendants who were found guilty for FDV offences in 2022–23 were Monetary penalties (25%), Custody in a correctional institution (19%), Good behaviour (including bonds) (19%) and Moderate penalty in the community (18%). The most common principal sentence varied by principal FDV offence. For FDV defendants who were found guilty of:

- Homicide and related offences, Sexual assault and related offences and Other dangerous or negligent acts, the majority were sentenced with Custody in a correctional institution (95%, 55%, 53% respectively).

- Stalking, harassment and threatening behaviour, the most common sentence was Moderate penalty in the community (29%).

- Abduction/harassment, Property damage and Breach of violence order, the most common sentence was Monetary penalties (26%, 32%, 38% respectively) (ABS 2024a).

4 in 5 (80%) finalised family and domestic violence defendants in 2022–23 were male.

Of finalised FDV defendants in 2022–23, 4 in 5 (80%, or 80,200) were male and 1 in 5 (20%, or 19,700) were female (ABS 2024a).

The pattern for the most common principal FDV offence among all finalised FDV defendants (including transfers to other court levels) was similar for males and females:

- Acts intended to cause injury was the most common offence for both (48% or 38,800 and 54% or 10,600, respectively)

- followed by Breach of violence order (40%, or 31,900 and 35%, or 6,900, respectively), and all other FDV offences (ABS 2024a).

Most finalised FDV defendants were aged 25–29 (15% or 14,600), 30–34 (16% or 15,900) or 35–39 (15% or 15,400) with decreasing numbers for younger (5.6% for people aged 10–19) and older age groups (7.0% for people aged 55 years and over) (ABS 2024a).

Sexual assault and related offences

About 3 in 5 (59%) defendants finalised for Sexual assault and related offences in 2022–23 were found guilty.

About 8,000 defendants were ‘finalised’ for Sexual assault and related offences in 2022–23. Of these:

- about 3 in 5 finalised defendants were found guilty (59%, or 4,700).

- about 1 in 7 finalised defendants were acquitted (15%, or 1,200).

- about 1 in 4 were withdrawn by the prosecution (25%, or 2,000) (ABS 2024a).

As noted previously, on this topic page ‘finalised’ indicates that charges have been finalised by methods other than ‘transfer to other court levels’ (see Data sources and technical notes). The number of defendants finalised for Sexual assault and related offences by transfer to other court levels in 2022–23 was 3,700 compared with 8,000 finalised by other methods (ABS 2024a).

Almost all (97%) finalised defendants for Sexual assault and related offences in 2022–23 were male.

Almost all finalised defendants with a principal offence of Sexual assault and related offences in 2022–23 were male (97%, or 7,700) with only 3.3% (260) female. The proportion of defendants across 5-year age groups were similar for those aged 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39 and 40–44 years with each contributing to between 10% and 12% of all defendants (ABS 2024a).

Family courts

Experiences of family violence were alleged in over 4 in 5 (83%) applications for parenting or parenting and property orders in 2022–23.

A Notice of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk of Family Violence (Notice) is a form that is used during proceedings related to parenting orders to notify the court whether a child or person involved in proceedings is at risk of or has experienced abuse and/or family violence. This includes exposure to family violence, as well as other circumstances related to the experiences and/or risks of harm to the child (risk factors) (FCFCOA n.d.a).

Other risk factors include allegations that:

- drug, alcohol or substance misuse by a party or mental health issues of a party had caused harm to a child or posed a risk of harm to a child

- a child was at risk of being abducted

- there had been recent threats made to harm a child or other person relevant to the proceedings (FCFCOA 2023).

From 31 October 2020 it became compulsory in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia to file a Notice with applications for parenting orders including when filing an Initiating Application, Response to initiating Application, or Application for Consent Orders or when making new allegations of child abuse or family violence after filing or when the case is transferred to the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (FCFCOA n.d.a).

Data from the Notices of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk filed with applications for final orders seeking parenting or parenting and property orders with the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia in 2022–23 indicated that:

- in over 4 in 5 (83%) matters, one or more parties alleged they have experienced family violence

- in over 7 in 10 (72%) matters, one or more parties alleged that a child had been abused or was at risk of child abuse

- in almost 7 in 10 (69%) matters, there were 4 or more risk factors alleged by either party (FCFCOA 2023).

The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia have recently launched a new case management model that aims to better prioritise and address cases in which there is increased risk of harm from FDV (see Box 9).

The Lighthouse model is part of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia response to ensure that family safety risks are identified at the earliest point in proceedings and that case management decisions are risk-informed. After a successful pilot in Adelaide, Brisbane and Parramatta Federal Circuit Court registries (launched in December 2020), the model was adopted by all 15 family law registries on 28 November 2022 (FCFCOA n.d.b).

The Lighthouse model involves:

- early risk screening through a secure online platform

- early identification and management of family safety risks

- assessment and triage of cases by a specialised team who will provide support and refer the party to appropriate services

- safe, and suitable case management, including referring high risk cases to a dedicated court list, known as the Evatt List (FCFCOA n.d.b).

As part of the pilot, about 1,100 matters were placed on the Evatt List from 7 December 2020 to 27 November 2022. A risk screen was completed by over 7 in 10 parties (73%). Three in 5 (60%) risk screens completed were classified as high risk (with 17% medium risk and 23% low risk) (FCFCOA 2023).

High risk cases are reviewed by a Triage Counsellor and can involve a telephone conference with litigants for further risk assessment (a Triage Interview). This can provide more tailored service referrals and support. Among the 4,600 triage events since 28 November 2022, most high risk parties presented with multiple risk factors, including:

- family violence (58%)

- child abuse and neglect (43%)

- alcohol and/or drug misuse (35%) (FCFCOA 2023).

After a review by a Triage Counsellor some high-risk matters may be referred to the Evatt list. Matters on the Evatt list receive intensive case management and resources during family law proceedings and are allocated dedicated Judges, Senior Judicial Registrars, Evatt List Judicial Registrars, Court Child Experts and court staff (FCFCOA 2023).

There were about 1,100 matters placed on the Evatt List in 2022–23 (FCFCOA 2023).

In 2022–23, about 125 Family Court cases were started that involve serious allegations of child physical abuse and/or sexual abuse.

In 2022–23, about 125 cases involving serious allegations of physical abuse and/or sexual abuse of a child were started in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, and about 93 cases were finalised (FCFCOA 2023). These cases are referred to as Magellan cases, and undergo special case management by a team consisting of a judge, a registrar and a family consultant. Typically, a Magellan case is addressed by the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia where one (or both) parties have raised serious allegations of sexual abuse or physical abuse of children in a parenting dispute (FCFCOA 2023).

Has it changed over time?

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began there has been an increase in deferrals and delays across all court proceedings. This has been due, in part, to complications related to conducting proceedings electronically and the effect of public health measures such as stay-at-home orders. Hence, changes over time and differences between states and territories may reflect these effects rather than, for example, crime rates or sentencing changes (ABS 2024a; FCOA 2021).

Civil courts– Domestic violence orders

The proportion of finalised applications in the Magistrates’ court involving DVOs decreased from 51% in 2021–22 to 47% in 2022–23 (Productivity Commission 2024; Table 2).

| Year | Finalised applications involving DVOs ('000) | Proportion of all civil cases |

|---|---|---|

| 2018–19 | 120.9 | 35% |

| 2019–20 | 110.6 | 33% |

| 2020–21 | 125.2 | 41% |

| 2021–22 | 135.4 | 51% |

| 2022–23 | 133.3 | 47% |

Notes:

- In Tasmania, police can issue Police Family Violence Orders (PFVOs) which are more numerous than court-issued orders. PFVOs are excluded from this table.

- Finalised applications involving DVOs only includes originating applications and non-appeal cases.

- Finalised applications includes transfers to other court levels.

Source: Productivity Commission 2024.

Criminal courts

Family and domestic violence offences over time

Between 2019–20 and 2022–23, there was a 55% increase in the total number of finalised defendants for FDV offences in Australia (from 64,500 to 99,900) (ABS 2024a). The number increased for all states and territories over this period (Table 3). Changes over time may reflect an improved methodology for identifying FDV-related offences that was introduced in South Australia and Western Australia in 2021–22 (ABS 2024b).

| State or Territory | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | % change 2019–20 to 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW | 25,083 | 32,995 | 30,396 | 37,695 | 50% increase |

| Vic | 14,126 | 12,293 | 17,944 | 21,589 | 53% increase |

| Qld | 12,754 | 18,436 | 19,486 | 22,931 | 80% increase |

| WA | 5,352 | 5,282 | 6,935 | 7,999 | n.p. |

| SA | 2,403 | 2,731 | 3,679 | 3,711 | n.p. |

| Tas | 1,493 | 1,821 | 1,715 | 1,582 | 6.0% increase |

| ACT | 529 | 616 | 587 | 757 | 43% increase |

| NT | 2,790 | 3,371 | 3,107 | 3,704 | 33% increase |

| Australia | 64,530 | 77,545 | 83,849 | 99,932 | 55% increase |

n.p.: Data not published.

Notes:

- Defendants finalised excludes those finalised through transfer to other court levels, see Data sources and technical notes.

- Court operations in all three financial years were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and changes may reflect these impacts rather than, for example, crime rates or sentencing changes.

- Changes over time may reflect an improved methodology for identifying FDV-related offences that was introduced in South Australia and Western Australia in 2021–22.

- Due to perturbation, component cells may not add to total.

Source: ABS 2024a.

Sexual assault and related offences over time

The number of defendants finalised for Sexual assault and related offences has generally increased between 2010–11 and 2022–23.

Between 2010–11 and 2022–23, the number of defendants finalised (including transfers to other court levels) for Sexual assault and related offences has generally increased, with the lowest number in 2013–14 (5,200) and the highest in 2022‒23 (about 8,000) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Defendants finalised for Sexual assault and related offences, 2010–11 to 2022–23

| Year | Finalised defendants |

|---|---|

| 2010–11 | 5,446 |

| 2011–12 | 5,309 |

| 2012–13 | 5,252 |

| 2013–14 | 5,216 |

| 2014–15 | 5,718 |

| 2015–16 | 5,835 |

| 2016–17 | 6,552 |

| 2017–18 | 6,770 |

| 2018–19 | 6,917 |

| 2019–20 | 6,392 |

| 2020–21 | 6,760 |

| 2021–22 | 7,340 |

| 2022–23 | 7,971 |

Notes:

- Finalised defendants includes those finalised through transfer to other court levels.

- The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in restrictions that affected the volume of defendants finalised in the Criminal Courts between 2019–20 and 2021–22. This context should be considered when comparing the Criminal Courts data over time.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ABS Criminal Courts

|

Data source overview

Family Courts

Notices of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk of Family Violence were increasing over time before they became compulsory.

Between 2014–15 and 2019–20, the number of cases in which a Notice was filed increased (from about 470 cases in 2014–15 to about 740 in 2019–20) (FCOA 2019, 2020).

This may have reflected an increase in the extent to which violence plays a role in Family Court cases and/or growing awareness of family violence in the community. Note that these cases do not include those dealt with in the Family Court of Western Australia (FCOA 2020).

As it became compulsory to file a Notice with every initiating application seeking parenting orders from 31 October 2020, changes in notices over time no longer relate to changes in allegations of abuse.

The number of Magellan cases (cases involving serious allegations of physical abuse and/or sexual abuse of a child) that were started and finalised each year has varied between 2020–21 and 2022–23 (Figure 4; FCFCOA 2023).

Figure 4: Magellan cases, 2020–21 to 2022–23

| Year | Magellan cases started | Magellan cases finalised |

|---|---|---|

| 2020–21 | 111 | 66 |

| 2021–22 | 110 | 130 |

| 2022–23 | 123 | 93 |

Note:

- Magellan cases are cases involving serious allegations of child abuse or harm, including physical abuse, sexual abuse or exposure to recent, significant and/or escalating family violence resulting in serious psychological harm.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia

|

Data source overview

More information

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2009) 4529.0 – Conceptual framework for family and domestic violence. 2009 – Additional terminology used in relation to family and domestic violence, ABS website, accessed 6 June 2023.

ABS (2011) Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification, 2011, ABS website, accessed 20 October 2022.

ABS (2024a) Criminal Courts, Australia, ABS website, accessed 12 April 2024.

ABS (2024b) Criminal Courts, Australia methodology, ABS website, accessed 12 April 2024.

ABS (2024c) Legal assistance services, ABS website, accessed 14 May 2024.

AGD (Attorney-General’s Department) (2022) The Meeting of Attorneys-General work plan to strengthen criminal justice responses to sexual assault 2022–2027, AGD, accessed 24 October 2022.

AGD (n.d.a) Legal assistance services, AGD website, accessed 15 August 2022.

AGD (n.d.b) National Domestic Violence Order Scheme, AGD website, accessed 15 August 2022.

AGD (n.dc) Specialist domestic violence assistance, AGD website, accessed 23 August 2022.

ALRC and NSW LRC (Australian Law Reform Commission and New South Wales Law Reform Commission) (2010) Family violence: A national legal response, Australian Government, accessed 25 October 2022.

ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) (2021) Interventions for perpetrators of domestic, family and sexual violence in Australia, ANROWS, accessed 23 August 2022.

ARTD consultants (2021) Southport Specialist Domestic and Family Violence Court: Process and outcomes evaluation 2017–21, ARTD consultants, Queensland Courts website, accessed 19 August 2022.

Bell C and Coates D (2022) The effectiveness of interventions for perpetrators of domestic and family violence: An overview of findings from reviews, ANROWS, accessed 20 December 2023.

CLCA (Community Legal Centres Australia) (2019) About community legal centres Australia, CLCA website, accessed 21 October 2022.

Deck SL, Powell MB, Goodman-Delahunty J and Westera N (2022) Are all complainants of sexual assault vulnerable? Views of Australian criminal justice professionals on evidence sharing process The International Journal of Evidence & Proof, 26(1):20–33, doi:10.1177/13657127211060556

Douglas H (2018) Legal systems abuse and coercive control, Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(1):84–99, doi:10.1177/1748895817728380.

Douglas H and Ehler H (2022) National domestic and family violence bench book, AIJA and AGD, accessed 22 August 2022.

Dowling C, Morgan A, Hulme S, Manning M and Wong G (2018) Protection orders for domestic violence: A systematic review, Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 21 August 2022.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 19 October 2022.

Family Relationships Online (2022) Family relationship centres, Family Relationships Online website, accessed 21 October 2022.

FCFCOA (Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia) (2023) 2022-23 Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1) and (Division 2) annual report, FCFCOA website, accessed 14 June 2023.

FCFCOA (n.d.a) Notice of child abuse, family violence or risk, FCFCOA website, accessed 15 April 2024.

FCFCOA (n.d.b) Lighthouse – Frequently asked questions, FCFCOA website, accessed 15 April 2024.

FCOA (Family Court of Australia) (2019) Annual Report 2018–19, FCOA, accessed 16 August 2022.

FCOA (2020) Annual Report 2019–2020, FCOA, accessed 16 August 2022.

FCOA (2021) Annual Report 2020–2021, FCOA, accessed 16 August 2022.

Jeffries S, Wood WR and Russel T (2021) 'Adult restorative justice and gendered violence: Practitioner and service provider viewpoints from Queensland, Australia', Laws, 10(13), doi:10.3390/laws10010013, accessed 20 December 2023.

Larsen JJ (2014) Restorative justice in the Australian criminal justice system, AIC, accessed 20 December 2023.

Mackay E, Gibson A, Lam H and Beecham D (2015) Perpetrator interventions in Australia: Part one – Literature review. State of knowledge paper, ANROWS, accessed 6 June 2023.

McGowan J (2016) Specialist family violence courts, Monash Gender and Family Violence Centre – Research brief, Monash University, doi:10.26180/5d198c315e0d2

Nancarrow H, Thomas K, Ringland V and Modini T (2020) Accurately identifying the “person most in need of protection” in domestic and family violence law, ANROWS, accessed 24 October 2022.

National Legal Aid (2019a) Family Advocacy and Support Service, Family violence law help website, accessed 15 August 2022.

National Legal Aid (2019b) What is child protection law?, Family violence law help website, accessed 15 August 2022.

NATSILS (National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service) (2022) NATSILS website, accessed 21 October 2022.

NFVPLS (National Family Violence Prevention and Legal Services) (2022) Who we are, NFVPLS website, accessed 23 August 2022.

Productivity Commission (2024) Report on Government Services 2024 Part C, Section 7, Courts, Productivity Commission website, accessed 22 February 2024.

SCSPLA (Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs) (2017) A better family law system to support and protect those affected by family violence – 2. Overview of the family law system, SCSPLA, Parliament of Australia, accessed 24 October 2022.

SCSPLA (2021) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, SCSPLA, Parliament of Australia, accessed 22 August 2022.

Taylor A, Ibrahim N, Wakefield S and Finn K (2015) Domestic and family violence protection orders in Australia: An investigation of information sharing and enforcement: State of knowledge paper, ANROWS, accessed 22 August 2022.

Webster K, Diemer K, Honey N, Mannix S, Mickle J, Morgan J, Parkes A, Politoff V, Powell A, Stubbs J and Ward A (2018) Australians’ attitudes to violence against women and gender equality. Findings from the 2017 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), ANROWS, accessed 14 September 2022.

- Previous page Housing

- Next page Financial support and workplace responses