Young women

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

Family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) affects people of all ages and from all backgrounds, but predominantly perpetrated by men against women and children. There are also differences in the experience of FDSV across age groups for women. Young women are more at risk of experiencing physical and sexual intimate partner violence (IPV), sexual violence and harassment compared to older women, while non-physical forms of violence (such as emotional abuse) are similar across age groups in many countries (Stöckl et al. 2014; ABS 2023a, 2023b; Pathak et al. 2019).

Definitions for what constitutes the age range for young women vary across data collections and reporting. This topic page defines young women as aged 15–34 to reflect age groups used in key data sources. However, the following sections will illustrate that the nature of violence can still vary within this broad age group.

What do we know?

There are several reasons why physical and sexual IPV may be less common among older women. One potential explanation is that the decrease is part of the general trend that criminal activity reduces with age, another is that couples who form early unions may face unique relationship stressors that can contribute to IPV, such as early pregnancies, employment instability, and financial difficulties (Stöckl et al. 2014). It is important to note that FDSV prevalence among older women are often underreported, due to various factors such as:

- generational differences in cultural norms (e.g. normalisation of violent behaviours, conservative attitudes that women should play a passive role)

- fear of retaliation, abandonment, institutionalisation or ostracisation

- health (e.g. functional dependence/disability, cognitive impairment)

- age-related shame in disclosing and/or seeking help (Qu et al. 2021; Beaularier et al. 2008; Pathak et al. 2019; WHO 2018).

For more information on FDSV among older women, please refer to the Older people topic page.

Impacts of FDSV victimisation among young women

Existing research indicates FDSV victimisation among young women can lead to adverse and/or long-lasting health impacts. Women who have experienced childhood abuse or household dysfunction can have higher long-term primary, allied and specialist healthcare costs, compared with women without these childhood experiences (Loxton et al. 2018). Women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse were also more likely to report poor general health and experience depression and bodily pain during adulthood than those who had not (Coles et al. 2018).

Associations also exist between childhood abuse and the experience of violence in adulthood. The 2016 ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS) found women who experienced childhood abuse were about 3 times as likely to experience sexual violence and partner violence as an adult than those who did not experience childhood abuse (ABS 2019a). In addition, an ANROWS study found that people aged 16–20 who had both witnessed violence between other family members and been subjected to child abuse were 9.2 times more likely to use violence in the home than those who had not experienced any child abuse (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022).

What do the data tell us?

Data are available across several surveys and administrative data sources to look at the prevalence, service responses and outcomes of FDSV among young women.

- ABS Personal Safety Survey

- ABS Recorded Crime, Victims

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

- AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) Collection

- ANROWS Adolescent Family Violence in Australia study

- ANROWS Technology-facilitated Abuse study

- Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey

- National Student Safety Survey

For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Young women experience more cohabiting partner violence and sexual violence than older women

Women’s exposure to violence differs across the age groups. The 2021-22 PSS found that the prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence by a cohabiting partner (partner violence) among women declined with age. One in 39 (2.6%) women aged 18-34 experienced partner violence in the 2 years before the survey, compared with 2.2% for those aged 35-54 and 0.6% for those aged 55 and over (ABS 2023a).

The prevalence of sexual violence by any perpetrator among women also decreased with age. One in 8 (12%) women aged 18-24 experienced sexual violence in the 2 years before the survey, compared with 4.5% of those aged 25-34, 2.5% of those aged 35-44, 1.9%* for those aged 45-54 and 0.5%* of those aged 55 and over (ABS 2023e).

Note that estimates marked with an asterisk (*) should be used with caution as they have a relative standard error between 25% and 50%.

Figure 1: Women who experienced cohabiting partner violence, sexual violence, partner emotional abuse and partner economic abuse in the 2 years before the survey, by age group, 2021–22

| Age group | Partner violence | Sexual violence | Partner emotional abuse | Partner economic abuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 2.2*% | 12.4% | 2.9*% | 2.6*% |

| 25-34 | 2.9% | 4.5% | 5.9% | 3.5% |

| 35-44 | 2.8% | 2.5% | 8.9% | 5.3% |

| 45-54 | 1.3*% | 1.9*% | 5.9% | 4.0% |

| 55+ | 0.6% | 0.5*% | 3.8% | 1.8% |

Note:

- Components are not able to be added together to produce a total. Where a person has experienced more than one type of violence or abuse, they are counted separately for each type they experienced.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

*: estimate has a relative standard error (RSE) between 25% and 50% and should be used with caution.

Source:

ABS PSS 2021–22

|

Data source overview

The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health asked 3 cohorts of women about their experiences of unwanted sexual activity in the 12 months prior to several time points during the study (recent sexual violence). Almost 4% of women aged 18–23 in 1996 experienced recent sexual violence, with the proportion maintaining at less than 2% once the cohort reached ages 22–27 in 2000. Similarly, almost 6% of women that were aged 18–24 in 2013 experienced recent sexual violence, with the proportion dropping to below 4% when the cohort reached ages 24–30 in 2019 (Townsend et al. 2022).

Young women are more likely to experience sexual harassment and stalking than older women

The 2021–22 PSS estimated that over 1 in 8 (13%, or 1.3 million) women and 1 in 22 (4.5%, or 427,000) men aged 18 and over had experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months before the survey. Of all age groups, women aged 18–24 were most likely to have experienced sexual harassment, with over 1 in 3 (35%, or 356,000) having experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months before the survey (ABS 2023b, 2023d) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Women who experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months before the survey, by age group, 2021–22

| Age group | Per cent |

|---|---|

| 18-24 | 35% |

| 25-34 | 20.8% |

| 35-44 | 12.5% |

| 45-54 | 9.0% |

| 55-64 | 6.3% |

| 65+ | 3.2% |

Note:

- Components are not able to be added together to produce a total.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ABS PSS 2021–22

|

Data source overview

The 2016 PSS estimated that 1 in 16 (6.4%, or 69,900) women aged 18–24 experienced stalking from a male in the 12 months before the survey, with this proportion decreasing with age (ABS 2017) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Women who experienced stalking by a male in the 12 months before the survey, by age group, 2016

| Age group | Per cent |

|---|---|

| 18-24 | 6.4% |

| 25-34 | 3.7% |

| 35-44 | 3.2% |

| 45-54 | 2.1% |

| 55-64 | 1.2% |

| 65+ | 0.9% |

Note:

- Components are not able to be added together to produce a total.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ABS PSS 2016

|

Data source overview

A survey administered by the Australian Human Rights Commission in 2016 found that sexual violence was prevalent in universities across Australia. In 2021, Universities Australia funded the National Student Safety Survey (NSSS) as part of its Respect. Now. Always. initiative to further understand the extent and nature of the problem. The NSSS sampled over 43,800 Australian university students and found that compared to male respondents, female respondents were:

- more likely to have experienced sexual assault (6.0% compared with 2.1%) or harassment (21% compared with 7.6%) in a university setting, and

- more likely to have been sexually assaulted by a male perpetrator (97% compared with 44%).

The study also found that respondents aged 18–21 were most likely to report sexual harassment by a stranger or a student from their place of residence in their most impactful incident of harassment in a university context compared to older students. Meanwhile, respondents aged 22–24 were more likely to report sexual assault in a university context than other age groups.

For more information on sexual violence in Australia, please refer to the Sexual violence topic page.

Source: Heywood et al. 2022

Young women are more likely to experience sexual harassment at their workplace

The Australian Human Rights Commission conducted the fifth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces in 2022. The nationally representative study of over 10,000 respondents found that the proportion of women that had been sexually harassed at work in the last 5 years decreased with age between age group 15–17 and 50–64. Sixty per cent of women aged 15–17 had been sexually harassed at work in the last 5 years compared with 27% of those aged 50–64 (AHRC 2022) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Women that experienced workplace harassment in the last 5 years, by age group, 2022

| Age group | Per cent |

|---|---|

| 15-17* | 60% |

| 18-29 | 56% |

| 30-39 | 45% |

| 40-49 | 34% |

| 50-64 | 27% |

| 65+ | 36% |

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

*: small sample size and the data should be interpreted with caution.

Source:

AHRC National survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces

|

Data source overview

For more information on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces, please refer to Time for respect: Fifth National Survey on Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces.

Young women are more likely to experience technology-facilitated abuse than older women

Technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) involves the use of mobile and digital technologies in interpersonal harms, such as online harassment, image-based abuse, and monitoring behaviours (Powell et al. 2022). A nationally representative study of about 4,600 respondents on TFA found that younger women were more likely to report lifetime TFA victimisation compared to older women. Almost 3 in 4 (74%) female respondents aged 18–24 and 7 in 10 (71%) of those aged 25–34 reported having experienced TFA in their lifetime, with this proportion decreasing with age (Figure 5) (Powell et al. 2022).

Figure 5: Lifetime victimisation of technology-facilitated abuse for female respondents, by age group, 2022

| Age group | Per cent |

|---|---|

| 18-24 | 73.8% |

| 25-34 | 71.1% |

| 35-44 | 61.9% |

| 45-54 | 59.6% |

| 55-64 | 40.1% |

| 65-74 | 30.2% |

| 75+ | 20.9% |

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ANROWS Technology-Facilitated Abuse Survey

|

Data source overview

For more information on TFA, please refer to the Stalking and surveillance topic page.

What are the responses to FDSV for young people?

Young women are more likely to seek informal support for sexual assault than older women

The ABS PSS 2021-22 collected data on police contact and support-seeking behaviours among young women after experiencing sexual assault. In response to their most recent incident of sexual assault perpetrated by a male in the last 10 years, women aged 18–34 were:

- less likely (5.5%*) to contact police than those aged 35 and over (12%)

- more likely (52%) to seek informal support (including friends, family, people at work and spiritual advisors) than those aged 35 and over (35%) (ABS 2023e).

Please note that data marked with an * have a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Young women are more likely to use specialist homelessness services due to family and domestic violence than older women

Specialist homelessness service (SHS) agencies receive government funding to deliver services to support people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. The AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services collection reported that in 2022–23 the proportion of female SHS clients who have experienced FDV was highest for those aged 25–34 (24%) and decreased with age for age groups from 35–44 onwards (Figure 6; AIHW 2023b).

Figure 6: Specialist homelessness services female clients who have experienced FDV, by age group, 2022–23

| Age group | Per cent |

|---|---|

| 0–9 | 14.9% |

| 10–14 | 5.5% |

| 15–17 | 4.7% |

| 18–24 | 13.0% |

| 25–34 | 23.9% |

| 35–44 | 22.0% |

| 45–54 | 10.9% |

| 55–64 | 3.6% |

| 65+ | 1.5% |

Notes:

- 'Females' may also include clients recorded as 'other' sex as these data are combined for quality and confidentiality reasons.

- To minimise the risk of identifying individuals, a technique known as perturbation has been applied to randomly adjust cells. For this reason, discrepancies may occur between sums of the component items and reported totals, and data may not match other published sources.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

AIHW SHSC

|

Data source overview

In 2022–23, almost 1 in 4 (23%) women aged 18 and over who experienced FDV presented as single with child/ren (of any age). Proportions were highest for women aged 25–34 and 35–44 (27% for both age groups), compared with 20% for women aged 18–24 and 13% for women aged 45 and older (AIHW 2024).

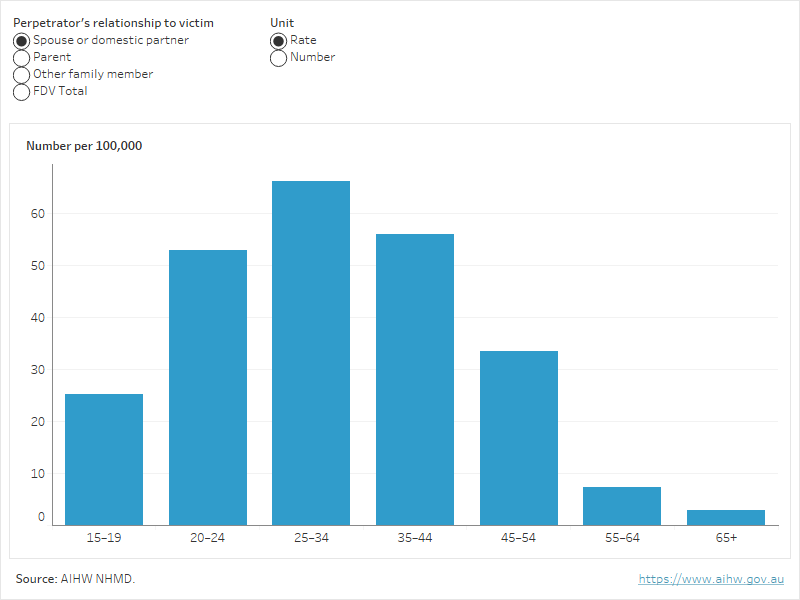

Younger women are more likely to be hospitalised for FDV-related injuries than older women

In 2021–22, the rate of hospitalisations for FDV-related injury was highest for females aged 25–34 (80 per 100,000 females), with this age group most likely to be hospitalised due to injury from spouse or domestic partner (66 per 100,000 females). Meanwhile, females aged 0–14 had the highest rate of hospitalisation due to injury from parents (4.2 per 100,000 females) (Figure 7) (AIHW 2023a).

Figure 7: Family and domestic violence hospitalisations for females, by relationship to perpetrator, 2021–22

Figure 7 shows the rate and number of family and domestic violence hospitalisations for females aged 15 and over in 2020-21 and 2021-22, disaggregated by the perpetrator's relationship to the victim and age group.

The proportion of hospitalisations for injuries related to sexual assault was also highest for females aged 25–34 (28%), compared with 18% for those aged 15–19 and 16% each for those aged 20–24, 35–44 and 45 and above (AIHW 2023a).

These data relate to people admitted to hospital and do not include presentations to emergency departments for FDV-related injury. Please refer to the Health services topic page for more information on FDSV hospitalisations.

Police responses

Younger women are more likely to be victims of sexual assault than older women

In 2022, police-recorded crime data showed younger women were more likely to be victims of sexual assault than older women. The most common age group at incident for victims was under 18 years (56%, or 15,000), compared with 30% (or 8,100) of females aged 18-34, 12% (or 3,100) of females aged 35–54, and 2.4% (or 650) of females aged 55 years and over (ABS 2023c).

Younger women were also more likely to be victims of FDV-related sexual assault than older women. The most common age group at incident for victims was under 18 years (59%, or 6,100), compared with 26% (or 2,700) of females aged 18–34, 13% (or 1,400) of females aged 35–54, and 1.2% (or 130) of females aged 55 years and over (ABS 2023c) (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Female victims of sexual assault, by age group, 2022

| Age group | All sexual assault | FDV-related sexual assault |

|---|---|---|

| <18 | 55.7% | 58.9% |

| 18-34 | 29.9% | 26.3% |

| 35-54 | 11.6% | 13.1% |

| 55+ | 2.4% | 1.2% |

Notes:

- Data have been randomly adjusted to avoid the release of confidential data and discrepancies may occur between sums of the component items and totals.

- Proportion represents the number of sexual assault or FDV-related sexual assault victims for an age group as a proportion of all female sexual assault or FDV-related sexual assault victims.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ABS Recorded Crime – Victims

|

Data source overview

Please refer to FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police for data on offences. For more information on adolescent family violence, please see Box 2 and Children and young people.

Adolescent family violence (AFV) is the use of family violence by a young person against their parent, carer, sibling or other family member within the home, which can include physical, emotional, psychological, verbal, financial and/or sexual abuse (RCFV 2016).

ANROWS administered a non-representative survey on 5,021 young people aged 16–20 living in Australia to evaluate their sociodemographic characteristics, current living arrangements, and their experiences of:

- witnessing violence between other family members

- being subjected to direct forms of abuse perpetrated by other family members

- their use of violence against other family members.

The study found that 1 in 5 (20%) respondents reported ever using violence against a family member, with verbal abuse (15%) and physical violence (10%) as the most common types of AFV used. Respondents assigned female at birth (23%) were more likely to report using violence in the home than those assigned male at birth (14%). Nine in 10 (90%) respondents assigned female at birth and 6 in 7 (86%) respondents assigned male at birth who had used AFV also reported they had experienced child abuse.

For more information on AFV in Australia, please refer to the Children and young people topic page.

Source: Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022

Impacts of COVID-19

We continue to learn about the impact of the emergency phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on FDSV, with some different patterns observed between research and national population prevalence data (Diemer 2023). As the methodologies differ, these data cannot be directly compared.

The 2021–22 ABS Personal Safety Survey, which was conducted from March 2021 to May 2022, found that intimate partner violence in the last 12 months for women aged 18 years and over decreased from 2.3% in 2016 to 1.5% in 2021–22. Results for 2021–22 were also lower than 2012 (2.1%) and 2005 (2.3%) (ABS 2023b). Comparable data for 2016 and 2021–22 are not available for younger women.

Between 16 February 2021 and 6 April 2021, the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) conducted an online survey of about 10,100 women aged 18 and over who had been in a relationship in the preceding year. Results found that in the 12 months before the survey, the pandemic coincided with first-time and escalating domestic violence in Australia for some women (Boxall and Morgan 2021a). Further analysis of these data found that younger women were more likely than older women to report having experienced physical and sexual violence and/or coercive control in the 3 months prior to survey. Women aged 18–24 were 8 times more likely to experience physical/sexual violence and 6 times more likely to experience coercive control than women aged 55 and over (Boxall and Morgan 2021b).

Please refer to the FDSV and COVID-19 topic page for more information.

Is it the same for everyone?

Young women are a diverse group, and experiences of violence and abuse can differ for various reasons. Although age and sex-specific data are limited for different population groups, they generally show that younger women are still more likely to experience FDSV than older women within sub-groups.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young women

There are limited national data on FDSV prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) young women. It is known that in 2014-15, First Nations women in the age groups 25–34 years and 35–44 years were most likely to have experienced FDV-related physical violence (14% for both groups), compared with 9.4% of those aged 15–24 and 5.4% of those aged 45 years and over (ABS 2019b). Similarly, a higher proportion of First Nations women hospitalised for FDV-related injury were aged 25–34 (34%) and 35–44 (25%) compared with those that were aged 24 years and under (21%) and 45 years and over (19%) (AIHW 2023a).

Please refer to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people topic page for more information.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer or asexual (LGBTIQA+) young women

There are no national data on the prevalence of FDSV among LGBTIQA+ young women. However, LGBTIQA+ people experience identity-based abuse in addition to all forms of violence that affect cisgender women (DSS 2022). Identity-based abuse includes any act that uses how a person identifies to threaten, undermine or isolate them, such as pressuring a person to conform to gender norms or undertake conversion practices (Gray et al. 2020; DSS 2022).

Data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health shows women aged 25–30 that did not identify as exclusively heterosexual were at increased risk of interpersonal violence, when compared with their exclusively heterosexual counterparts. Interpersonal violence includes physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, harassment and being in a violent relationship (Szalacha et al. 2017).

Please refer to the LGBTIQA+ topic page for more information.

Young women with disability

Women with disability or illness are more likely to experience IPV and sexual violence than those without disability or illness (Brownridge 2006; Royal Commission in Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability 2021). Younger women with disability are also more likely to experience sexual violence than older women with disability. Data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health shows 73% of women aged 24–30 living with disability or illness have reported experiencing sexual violence in their lifetime, compared with 55% of women aged 40–45 and 34% of women aged 68–73 (Townsend et al. 2022).

Please refer to the People with disability topic page for more information.

Culturally and linguistically diverse young women

There are limited national data on the prevalence of FDSV among young women from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds in Australia. A non-representative national study on migrant and refugee women’s safety and security found that, among the 1,400 respondents, those aged under 30 (16%) were more likely to report having experienced physical and/or sexual violence compared with 14% of those aged 30–44, 12% of those aged 45–64, and 10% of those aged 65 and over (Segrave et al. 2021).

It is also known that IPV can affect CALD girls as young as 12 years old and result in hospitalisation (MYSA 2017). Some CALD young women are in arranged marriages where leaving an abusive relationship could lead to ostracism from their support systems (MYSA 2017). Moreover, many CALD women do not recognise forms of IPV outside of physical violence that causes injury, particularly financial abuse and reproductive coercion (El-Murr 2018).

Please refer to the People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds topic page for more information.

Pregnant young women

Young women are at higher risk of experiencing IPV during pregnancy and in early motherhood. The Australian Institute of Family Studies found that young women aged 18–24 are more likely to experience FDV during pregnancy than older women (Campo 2015). Taft et al.’s (2004) study of 14,800 women aged 18–23 found that 27% of the women who had ever had a pregnancy reported having experienced IPV, compared with 8% of the women who had never been pregnant. However, it is unclear whether young women in Taft et al.’s (2004) study became pregnant as an outcome of violence or that becoming pregnant increased their likelihood of experiencing violence.

Please refer to the Pregnant people topic page for more information.

More information

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2017) Personal Safety, Australia, ABS website, accessed 15 December 2022.

ABS (2018) AIHW analysis of Personal Safety Survey, 2016, TableBuilder, accessed 12 December 2022.

ABS (2019a) Characteristics and outcomes of childhood abuse, ABS website, accessed 23 March 2023.

ABS (2019b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014–15, ABS website, accessed 17 January 2023.

ABS (2023a) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 5 February 2024.

ABS (2023b) Personal Safety, Australia, ABS website, accessed 4 April 2023.

ABS (2023c) Recorded Crime – Victims, ABS website, accessed 3 August 2023.

ABS (2023d) Sexual harassment, ABS website, accessed 11 December 2023.

ABS (2023e) Sexual violence, ABS website, accessed 13 September 2023.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) (2022) Time for respect: Fifth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces, AHRC, accessed 8 August 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 12 December 2022.

AIHW (2020) Sexual assault in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 12 December 2022.

AIHW (2021) Australia’s youth, Australian Government, accessed 21 April 2022.

AIHW (2023a) AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database.

AIHW (2023b) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2022–23, AIHW website, accessed 13 February 2024.

AIHW (2024) Specialist Homelessness Services Collection data cubes 2011–12 to 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 February 2024.

Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR and Newman FL (2008) Barriers to help-seeking for older women who experience intimate partner violence: a descriptive model, Journal of Women & Aging, 20(3–4), doi:10.1080/08952840801984543.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021a) Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of women in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), accessed 15 January 2023.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021b) ‘Who is most at risk of physical and sexual partner violence and coercive control during the COVID-19 pandemic?’, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 618, AIC, accessed 15 January 2023.

Brownridge D (2006) Partner violence against women with disabilities: prevalence, risks and explanations, Violence against Women, 12(9):805–822, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801206292681.

Campo (2015) Domestic and family violence in pregnancy and early parenthood: overview and emerging interventions, Australian Institute of Family Studies, accessed 20 January 2023.

Coles J, Lee A, Taft A, Mazza D and Loxton D (2018) Childhood sexual abuse and its association with adult physical and mental health: results from a national cohort of young Australian women, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(11):1929–1944, doi:10.1177/0886260514555270.

Diemer K (2023) The unexpected drop in intimate partner violence, University of Melbourne website, accessed 21 April 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032, DSS, accessed 10 November 2023.

El-Murr A (2018) Intimate partner violence in Australian refugee communities: Scoping review of issues and service responses, Australian Institute of Family Studies, accessed 20 January 2023.

Fitz-Gibbon K, Meyer S, Boxall H, Maher J and Roberts S (2022) Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts, ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety), accessed 20 March 2023.

Gray R, Walker T, Hamer J, Broady T, Kean J, Ling J and Bear B (2020) Developing LGBTQ programs for perpetrators and victim/survivors of domestic and family violence, ANROWS, accessed 25 January 2023.

Heywood W, Myers P, Powell A, Meikle G and Nguyen D (2022) National Student Safety Survey: report on the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual assault among university students in 2021, The Social Research Centre, accessed 21 March 2023.

Loxton D, Townsend N, Dolja-Gore X, Forder P and Coles J (2019) Adverse childhood experiences and healthcare costs in adult life, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 5:511–525, doi:10.1080/10538712.2018.1523814.

MYSA (Multicultural Youth South Australia) (2017) Written submission by Multicultural Youth South Australia Inc. (MYSA) – In response to the call for written submissions by the National Children’s Commissioner, MYSA, accessed 19 January 2023.

Pathak N, Dhairyawan R and Tariq S (2019) The experience of intimate partner violence among older women: a narrative review, Maturitas, 121:63–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.12.011.

Powell A, Flynn A and Hindes S (2022) Technology-facilitated abuse: national survey of Australian adults’ experiences, ANROWS, accessed 26 March 2023.

Qu L, Kaspiew R, Carson R, Roopani D, Maio JD, Harvey J and Horsfall B (2021) National elder abuse prevalence study: final report, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, accessed 9 August 2023.

RCFV (Royal Commission into Family Violence) (2016) Findings and recommendations, RCFV, accessed 25 January 2023.

Royal Commission in Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (2021) Nature and extent of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation against people with disability in Australia, Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health, accessed 24 January 2023.

Segrave M, Wickes R and Keel C (2021) Migrant and refugee women in Australia: the safety and security study, Monash University website, accessed 8 August 2023.

Stöckl H, March L, Pallitto C and Garcia-Moreno C (2014) Intimate partner violence among adolescents and young women: prevalence and associated factors in nine countries: a cross-sectional study, BMC Public Health, 14:751, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-751.

Szalacha LA, Hughes TL, McNair R and Loxton D (2017) Mental health, sexual identity, and interpersonal violence: findings from the Australian longitudinal women’s health study, BMC Women’s Health, 17:94, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0452-5.

Taft A, Watson L and Lee C (2004) Violence against young Australian women and association with reproductive events: a cross sectional analysis of a national population sample, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 28(4):324–329, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00438.x.

Townsend N, Loxton D, Egan N, Barnes I, Byrnes E and Forder P (2022) A life course approach to determining the prevalence and impact of sexual violence in Australia: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, ANROWS, accessed 15 December 2022.

WHO (World Health Organisation) (2018) Elder abuse: fact sheet, WHO, accessed 23 March 2023.

- Previous page Children and young people

- Next page Pregnant people