Housing

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

On this page

Key findings Understanding housing and FDSV How do specialist homelessness services respond to FDSV? What do the data tell us about homelessness in the context of FDV? Has SHS clients experiencing FDV changed over time? Is it the same for everyone? What else do we know? Related materialKey findings

- Of those assisted by specialist homelessness services in 2022–23 around 104,000 people, or 38% of all clients, have experienced FDV.

- The rate of specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced FDV increased by 13% between 2011–12 and 2022–23.

- Among specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced FDV, 9 in 10 were women (aged 15 or older) and children (0-14 years old).

Family and domestic violence (FDV) is the main reason women and children leave their homes in Australia (AHURI 2021). Many women and children leaving their homes may experience housing insecurity, and in some cases, homelessness (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022). For this reason, women and children affected by FDV are a national homelessness priority group in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA), which came into effect on 1 July 2018 (CFFR 2019). Additionally, the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032 identified housing as a priority response area (DSS 2022). Safety at home can also be a concern for people who have experienced sexual violence outside of the family, for example if the perpetrator lives nearby, or knows where they live.

Housing assistance provided by governments and community organisations is available to eligible people in Australia who may have difficulty securing stable and affordable housing. There are also specialist homelessness services (SHS) that can provide a specialised response service for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, including those who may need to leave their home due to family, domestic and/or sexual violence (FDSV) (DSS 2022).

This page focuses primarily on SHS data, as this is the only national housing-related collection which currently includes information on clients who have experienced family, domestic and sexual violence.

Understanding housing and FDSV

When violence occurs within the home, it can create an unsafe and unstable environment, leading some individuals and families to leave for their safety (AIHW 2023b). For many, leaving the home (either temporarily or permanently) can result in housing insecurity and/or homelessness due to a lack of housing options or barriers in accessing resources and support.

The 2021–22 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) estimated that almost 2 in 3 (64%, or about 867,000) women who experienced partner violence while living with a previous partner, moved away from home when the relationship finally ended (ABS 2023). Equivalent estimates for men from the 2021–22 PSS were not sufficiently reliable for reporting. However, estimates from the 2016 PSS indicate that around 3 in 5 (61%, or about 223,000) men who experienced partner violence while living with a previous partner, moved away from home when the relationship finally ended (ABS 2017).

Following final separation from a violent partner, many people experienced homelessness at some point (e.g. slept rough, stayed temporarily with a friend or relative, or in accommodation without a permanent address). For example, 2 in 3 women (67% or 577,000) relied on friends or relatives for accommodation (ABS 2023).

For some victim-survivors, lack of suitable housing options may lead them to stay in or return to a violent relationship (Flanagan et al. 2019). There is research suggesting that returning to a previously violent partner can increase the level of violence experienced by victim-survivors who return (Anderson 2003). Providing suitable options for secure long-term housing accommodation is essential to support victim-survivors leaving a violent relationship (ANROWS 2019; Flanagan et al. 2019).

The Safe Places Emergency Accommodation (Safe Places) Program was established under the Fourth Action Plan of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022. Safe Places is a capital works program for emergency accommodation for women and children leaving FDV. Additional funding to continue the Safe Places Program was announced as part of the Australian Government investment in women’s safety and the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032 (DSS 2023).

Housing assistance provided by the Australian and state and territory governments includes the provision of social housing (public housing, state owned and managed Indigenous housing, community housing and Indigenous community housing) and financial assistance:

- Social housing is generally allocated according to priority needs – people identified as having the greatest need (such as those at risk of homelessness, including people whose life or safety was threatened within their existing accommodation), and those with special needs for housing assistance (such as people with disability).

- Financial assistance includes Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) and Private Rent Assistance (PRA) to help with private rental market costs and Home Purchase Assistance (HPA) (AIHW 2023a).

For information about the financial supports available to those who have experienced violence, see Financial support and workplace responses.

For those experiencing FDSV, SHS can provide an immediate response and crisis support. However, the pathway into stable, secure and long-term housing can be challenging (Flanagan et al. 2019). Systemic barriers, such as limited supply of affordable housing, make it difficult for women and children affected by FDV to move from crisis or transitional accommodation into permanent, independent housing (Flanagan et al. 2019; ANROWS 2019).

Why is housing important for those leaving violent situations?

'A key aspect to being stable and free from violence was having housing. I was luckily placed into government housing which offers people stability and affordability while learning life skills. Things you wouldn’t have time for if you were in the private rental market.'

Kelly

People and families who are homeless or at risk of homelessness may be at risk of additional forms of violence and exploitation, including sexual violence, as well as other challenges such as poverty and poor health (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022). The co-occurrence of homelessness and FDV can also have a significant impact on the mental health and well-being of individuals and families. Experiencing violence and homelessness can lead to trauma, significant stress and other mental health issues, further compounding the difficulties faced when leaving situations involving FDV (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022; AIHW 2021). For more information see Health outcomes.

How do specialist homelessness services respond to FDSV?

Specialist homelessness services (SHS) deliver accommodation-related and personal services to people who seek support who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

SHS agencies vary in size and in the types of assistance they provide. Across Australia, agencies provide services aimed at prevention and early intervention, as well as crisis and post crisis assistance to support people experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness. For example, some agencies focus specifically on assisting people experiencing homelessness, while others deliver a broader range of services, including youth services, FDV services, and housing support services to those at risk of becoming homeless. The service types an agency provides range from basic, short-term interventions such as advice and information, meals and shower or laundry facilities through to more specialised, time-intensive services such as financial advice and counselling and professional legal services. Some people receive support from SHS agencies on multiple occasions and the reason for seeking support may differ (AIHW 2023b).

National data sources for measuring specialist homelessness services

SHS agencies that receive government funding are required to provide data to the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC). The SHSC includes data on clients, the services that were provided to them and the outcomes achieved for those clients. For more information about the SHSC, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Box 1 provides information about the National Housing and Homeless Agreement (NHHA) Performance Indicators.

Under the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA), there are 2 key indicators to measure national homelessness performance:

- the number of people who experience repeat homelessness; and

- the proportion of people who are at risk of homelessness who receive assistance to avoid homelessness (AIHW 2023b).

Data on women and children affected by FDV are collected against these indicators. However, these data are primarily used to report progress against the objectives and outcomes of the NHHA and may not reflect progress for addressing FDV specifically.

In 2022–23, for SHS clients affected by FDV:

- there were 15,500 women and children experiencing persistent homelessness (homeless for more than 7 months over a 24-month period); an increase of 2,400 since 2018–19.

- there were 7,900 women and children affected by family violence who returned to homelessness (that is, used homelessness services with periods of permanent housing in between, only to return to SHS since July 2011) (430 client decrease since 2018–19).

- 78% of women and children at risk of homelessness avoided homelessness (no change from 2018–19).

For more information see National Housing and Homelessness Agreement Performance Indicators.

What do the data tell us about homelessness in the context of FDV?

SHS clients who experience FDV

Examination of the number of SHS clients experiencing FDV provides an indication of the level of service response for this group. Data on people seeking support from SHS agencies are drawn from the AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC) (see Box 2). The AIHW Specialist homelessness services annual report includes additional details on Clients who have experienced family and domestic violence.

In the SHSC, a client is reported as experiencing FDV if they identified FDV as a reason for seeking assistance and/or one of the services they needed was FDV assistance. In this context, family and domestic violence is defined as physical or emotional abuse inflicted on the client by a family member.

The SHSC reports on clients experiencing FDV of any age, including both victim and perpetrator services provided.

Clients of SHS agencies are considered to be either experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness:

- Clients are considered to be experiencing homelessness if they are ’sleeping rough’ in non-conventional accommodation, such as on the street or in a park, staying in short-term or emergency accommodation or staying in a dwelling without tenure (couch surfing).

- Clients are considered to be at risk of homelessness if they are living in public or community housing, private or other housing or in institutional settings.

Agencies funded to provided SHS vary widely in terms of the services they provide and the service delivery frameworks they use. Each state and territory manage their own system for the assessment, intake, referral and ongoing case management of SHS clients. Changes implemented by states and territories in the delivery of services and their associated responses have the potential to impact SHSC annual data.

In the SHSC, there is also data available on clients who identified sexual abuse by a family member or non-related individual as a reason for seeking assistance, and clients who needed and/or were provided with assistance for incest/sexual assault. In 2022–23, there were around 4,800 clients who reported sexual abuse as a reason for seeking assistance. Due to the relatively small number of clients, further analysis on this client group was not undertaken for this page.

Source: AIHW 2023b.

-

38%

of all clients assisted by specialist homelessness services in 2022–23 had experienced FDV

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

In 2022–23, around 104,000 clients assisted by SHS agencies had experienced FDV, representing 38% of all SHS clients, and a population rate of 40 per 10,000. Of these, around 3 in 5 (62%) had previously been assisted by a SHS agency at least once since the collection started in July 2011.

SHS clients may be provided with multiple forms of assistance. Among the 104,000 clients who had experienced FDV in 2022-23:

- 67% (70,000) needed specific assistance for FDV, with 61,900 receiving this service

- 46% (48,100) needed short-term or emergency accommodation, with 33,500 receiving this service

- 44% (45,400) needed money for accommodation (for example, bond or rent) and transport, and/or other non-monetary assistance, such as clothing, food vouchers and tickets for public transport. Of those, 40,100 received this service (AIHW 2023b).

SHS clients may seek victim and/or perpetrator support. Among SHS clients aged 10 and over who had experienced FDV in 2022–23:

- 65% (52,000) needed victim support, with 45,600 receiving this service

- 4.6% (3,700) needed perpetrator support, with 2,300 receiving this service

- 3.0% (2,400) needed victim and perpetrator support, with 1,400 receiving this service (AIHW 2023b).

Note, these groups are not mutually exclusive and clients can be counted in more than one group.

For information on health-related services for SHS clients, see also Health services.

The Specialist homelessness service usage and receipt of income support for people transitioning from out-of-home care report includes comparison data on SHS usage between clients in the period 2011–2021 who had experienced FDV (FDV cohort) and those who had not (non-FDV cohort). It found that the FDV cohort was more likely to receive SHS support for longer periods than the non-FDV cohort:

- 1 in 4 (25%) had received SHS support for over one year, compared with 11% for the non-FDV cohort

- over 1 in 7 (15%) had 11 or more support periods, compared with 2.9% for the non-FDV cohort (AIHW 2023c).

The report also found that compared with the non-FDV cohort, the FDV cohort were:

- 3.8 times as likely to need family services

- 2.7 times as likely to need legal or financial services

- 2.7 times as likely to need immigration or cultural services

- 2.6 times as likely to need disability services

- 2.3 times as likely to need drugs or alcohol services

- 2.3 times as likely to need mental health services (AIHW 2023c).

Fewer were experiencing homelessness at the end of support

Information on where clients were residing before and after they were supported by a SHS agency provides some insights on housing outcomes for those who have experienced FDV. Among clients who have experienced FDV whose support ended in 2022–23:

- More than 2 in 5 (42% or 9,400 clients) who were experiencing homelessness at the start of support were housed at the end of support.

- Almost 9 in 10 (88% or 30,000 clients) who were at risk of homelessness at the start of support were housed at the end of support (primarily in private rental accommodation (20,600 clients or 60%)).

It is important to note that some clients may seek assistance from SHS agencies again in the future.

Has SHS clients experiencing FDV changed over time?

The rate of specialist homelessness services clients across Australia who have experienced FDV increased by 13% between 2011–12 and 2022–23.

Among SHS clients who experienced FDV, the rate of clients between 2011–12 to 2022–23:

- increased by 13% from 36 per 10,000 population to 40 per 10,000

- increased on average by a rate of 1.1% per year

- increased for all jurisdictions except Western Australia, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory (Figure 1, AIHW 2023b).

Changes over time for Victoria should be interpreted with caution due to changes in practice which may result in a decrease in FDV client numbers since 2017–18 (AIHW 2023b).

See also FDSV and COVID-19.

Figure 1: Specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced FDV, by state/territory, 2011–12 to 2022–23

| Year | New South Wales | Victoria | Queensland | Western Australia | South Australia | Tasmania | Australian Capital Territory | Northern Territory | National |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | 25.6 | 55.5 | 23.6 | 38.9 | 40.5 | 24.5 | 38.1 | 120.8 | 35.6 |

| 2012–13 | 24.2 | 54.4 | 24.2 | 31.6 | 42.0 | 24.1 | 38.2 | 118.3 | 34.3 |

| 2013–14 | 24.9 | 61.8 | 24.8 | 33.9 | 39.7 | 27.5 | 39.8 | 112.8 | 36.7 |

| 2014–15 | 23.1 | 70.2 | 26.1 | 38.1 | 40.8 | 33.8 | 39.8 | 134.8 | 39.3 |

| 2015–16 | 30.4 | 75.8 | 28.0 | 42.8 | 42.7 | 42.2 | 40.3 | 144.4 | 44.3 |

| 2016–17 | 33.2 | 81.1 | 29.6 | 42.5 | 43.7 | 43.9 | 39.3 | 189.0 | 47.4 |

| 2017–18 | 33.9 | 90.0 | 28.4 | 41.4 | 40.5 | 34.6 | 35.7 | 195.7 | 49.2 |

| 2018–19 | 35.0 | 79.1 | 29.2 | 41.1 | 38.5 | 32.6 | 29.9 | 188.2 | 46.6 |

| 2019–20 | 34.1 | 81.4 | 30.6 | 39.2 | 36.6 | 32.4 | 37.1 | 183.0 | 47.0 |

| 2020–21 | 34.8 | 76.8 | 27.6 | 37.3 | 34.3 | 30.4 | 36.5 | 200.1 | 45.3 |

| 2021–22 | 32.4 | 70.3 | 25.9 | 36.8 | 29.1 | 30.7 | 33.3 | 192.8 | 41.9 |

| 2022–23 | 31.9 | 61.7 | 27.2 | 38.6 | 29.0 | 31.4 | 32.4 | 204.5 | 40.1 |

Note:

- Discrepancies may occur between sums of component items and reported totals due to rounding and/or clients accessing services in more than one state or territory.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

AIHW SHSC

|

Data source overview

Is it the same for everyone?

Among specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced FDV, 9 in 10 were women and children.

Some population groups may be at higher risk of homelessness due to FDV. Understanding which groups are at higher risk, can be used to inform the development of more targeted programs and services for these clients.

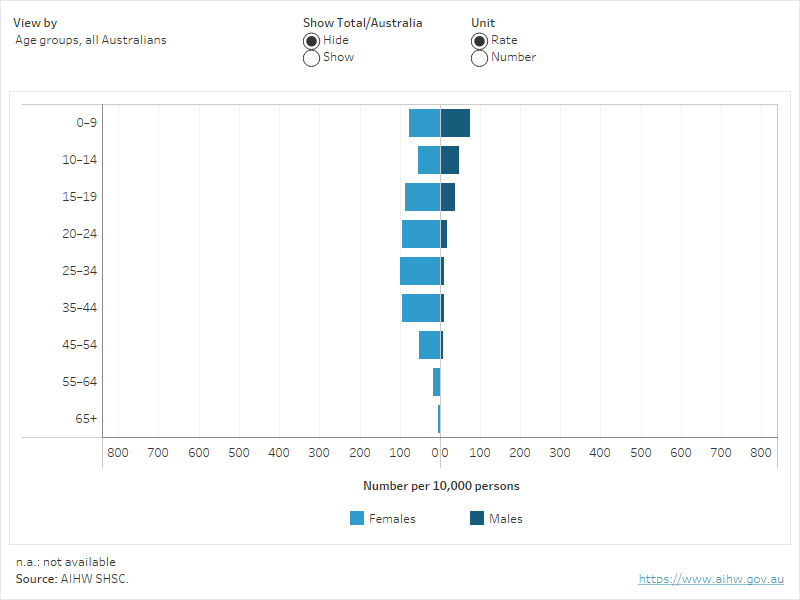

Figure 2 shows that of the 104,000 clients in 2022–23 who have experienced FDV:

- 9 in 10 clients were women and children. Around 6 in 10 (60% or around 62,300 clients) were females aged 15 and older, and a further 3 in 10 (31% or 32,100 clients) were children aged 0-14 years. See also Mothers and their children, Young women, and Children and young people.

- Just over 1 in 4 (29% or around 29,400 clients) were First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) people. See also Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- 1 in 6 (18%, or around 18,600 clients) spoke a main language other than English at home.

- Around 3 in 5 (61%, or around 63,100 clients) were in Major cities

- Almost 1 in 10 (7.7% or 8,100 clients) were living with disability. See also People with disability.

Figure 2: Specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced FDV, for select population groups, 2022–23

Figure 2 allows users to explore the number and rate of SHS clients who have experienced FDV, for select population groups.

SHS clients who experience FDV may also experience other vulnerabilities, such as mental health issues and problematic drug or alcohol use. Of the 80,400 clients aged over 10 who have experienced FDV, many had additional vulnerabilities – 12% reported experiencing problematic drug or alcohol use, and 42% had a current mental health issue. See also Factors associated with FDSV.

The co-occurrence of FDSV and homelessness is especially heightened for children and young people, who face increased risks of violence, interruptions to education, and repeat homelessness. Experiencing homelessness can limit access to medicine, treatment and basic hygiene and expose young people to sexual exploitation, violence and social isolation. Young people can also experience high levels of mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, behavioural problems and alcohol and drug misuse. Due to a combination of these factors, homeless young people face a high mortality rate when compared with the general population and represent a priority group under the Commonwealth Government National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA) to address the national housing crisis (see Box 1) (Aldridge et al. 2017; Heerde & Patton 2020; AIHW 2021).

What else do we know?

Many female SHS clients who have experienced FDV were long term clients

Analysis of the SHS longitudinal data set, provided insight into the patterns of support for female clients experiencing FDV over time. The study focused on a cohort of nearly 55,500 females aged 18 and over, who during 2015–16 were SHS clients that have experienced FDV. Of these, nearly half (47%) had used specialist homelessness services in the past 4 years (2011–12 to 2014–15) and 45% continued to use services in the 4 years after 2015-16. Almost 1 in 3 (29%) were long-term clients, who needed SHS support over a 10-year period (AIHW 2022).

This cohort were also 8 times more likely to need assistance for incest or sexual assault, and almost 6 times more likely to require court support, compared to women clients without a FDV experience in 2015–16 (AIHW 2022). For further details, see Specialist homelessness services: Female clients with family and domestic violence experience in 2015–16.

Victim-survivors of violence often bear the costs for leaving the family home

More than 1 in 2 (55%) women who permanently left a violent partner moved out of their home, while their partner remained in the home.

According to the 2021–22 ABS PSS, an estimated 755,000 women (55%) who permanently left a violent previous partner reported that only they, not their partner, had moved out of their home (ABS 2023). While equivalent 2021–22 data for men are not sufficiently reliable for reporting, 2016 data showed that an estimated 180,000 men (49%) who permanently left a violent previous partner reported that only they, not their partner, had moved out of their home (ABS 2017).

In March 2021, the Parliamentary Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence found that victim-survivors of violence often bear the costs for leaving the relationship, the family home and their community. Relocation expenses can include deposits or rental bonds for new dwellings, travel costs, furnishing costs and safety upgrades. These costs, in addition to other costs such as legal and medical costs and the costs of providing for any dependents, may result in economic instability and the accumulation of debt (HRSCSPLA 2021).

The inquiry recommended federal and state and territory governments consider funding for emergency accommodation for people who use violence (perpetrators) in order to prevent victim-survivors being forced to flee their homes or continue residing in a violent home (see Box 4). This would reduce the burden on victim-survivors and hold perpetrators accountable for their behaviour (HRSCSPLA 2021).

The National Plan Victim-Survivor Advocates Consultation Final Report provided by Monash University’s Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre noted some victim-survivors advocated for further investment in perpetrator housing pathways. Increasing housing for perpetrators would support primary victim-survivors to remain in the home.

Some state and Federal level initiatives have been developed, for example, the Victorian Government committed additional funding in August 2020 to increase short- and long-term accommodation options for perpetrators of family violence and people at risk of using family violence. The strategy was positioned as part of an increased government commitment to ensuring perpetrator visibility at all points of the system response to family violence. At the federal level, the Commonwealth Government funds the Keeping Women Safe in their Homes program, in which they have invested $34.6 million since 2015−16. See more at Who uses violence?

Source: Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022.

More information

- Specialist homelessness services annual report – Clients who have experienced family and domestic violence

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways – Female clients with family and domestic violence experience in 2015–16

- National Housing and Homelessness Agreement Performance Indicators (see ‘women and children affected by FDV’ cohort)

- Specialist Homelessness Services: monthly data

ABS (2017) Personal safety, Australia, 2016, ABS website, accessed 22 June 2022.

ABS (2023) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

AHURI (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute) (2021) Housing, homelessness and domestic and family violence, AHURI, accessed 16 November 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Homelessness and overcrowding, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 9 February 2023.

AIHW (2022) Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients with family and domestic violence experience in 2015–16, AIHW, accessed 2 August 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Housing assistance in Australia, AIHW, accessed 14 July 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2022–23, AIHW, accessed 9 January 2024.

AIHW (2023c) Specialist homelessness service usage and receipt of income support for people transitioning from out-of-home care, AIHW, accessed 20 March 2024.

Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, Nordentoft M, Luchenski SA, Hartwell G, Tweed EJ, Lewer D, Katikireddi SV and Hayward AC (2017) Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis, The Lancet, 391(10117):241–250, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X.

Anderson D (2003) The impact of subsequent violence of returning to an abusive partner, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, doi:10.3138/jcfs.34.1.93.

ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) (2019) Domestic and family violence, housing insecurity and homelessness: Research synthesis (2nd edition), ANROWS, accessed 6 June 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) The National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032, DSS, accessed 6 June 2023.

DSS (2023) Safe Places Emergency Accommodation (Safe Places) Program, DSS, accessed 6 June 2023.

CFFR (Council on Federal Financial Relations) (2019) National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, Department of the Treasury, accessed 16 November 2022.

Fitz-Gibbon K, Reeves E, Gelb K, McGowan J, Segrave M, Meyer S and Maher JM (2022) National Plan Victim-Survivor Advocates Consultation Final Report, Monash University, accessed 6 June 2023.

Flanagan K, Blunden H, Valentine K & Henriette J (2019) Housing outcomes after domestic and family violence, AHURI Final Report 311, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, accessed 21 November 2022.

Heerde JA and Patton GC (2020) The vulnerability of young homeless people, The Lancet Public Health, 5(6):E302–E303, doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30121-3.

HRSCSPLA (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs) (2021) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Parliament of Australia, accessed 21 November 2022.

- Previous page Child protection

- Next page Legal systems