Specialist perpetrator interventions

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

A broad range of services and service providers may respond to FDSV when it occurs. A subset of these services work directly with perpetrators with the goal to hold perpetrators to account for their violence, and stop violence from recurring in the future. These services are often referred to as ‘perpetrator interventions’.

The majority of perpetrator interventions fall into 2 categories: police and legal responses, and behaviour change interventions. Understanding how many people access the services, and the different pathways that people take through these services can help inform the development and evaluation of policies, programs and services to prevent and better respond to FDSV.

This topic page builds on FDV reported to police, Sexual assault reported to police and Legal systems to look specifically at behaviour change interventions, and discuss where they fit into the broader perpetrator interventions system.

What are perpetrator interventions?

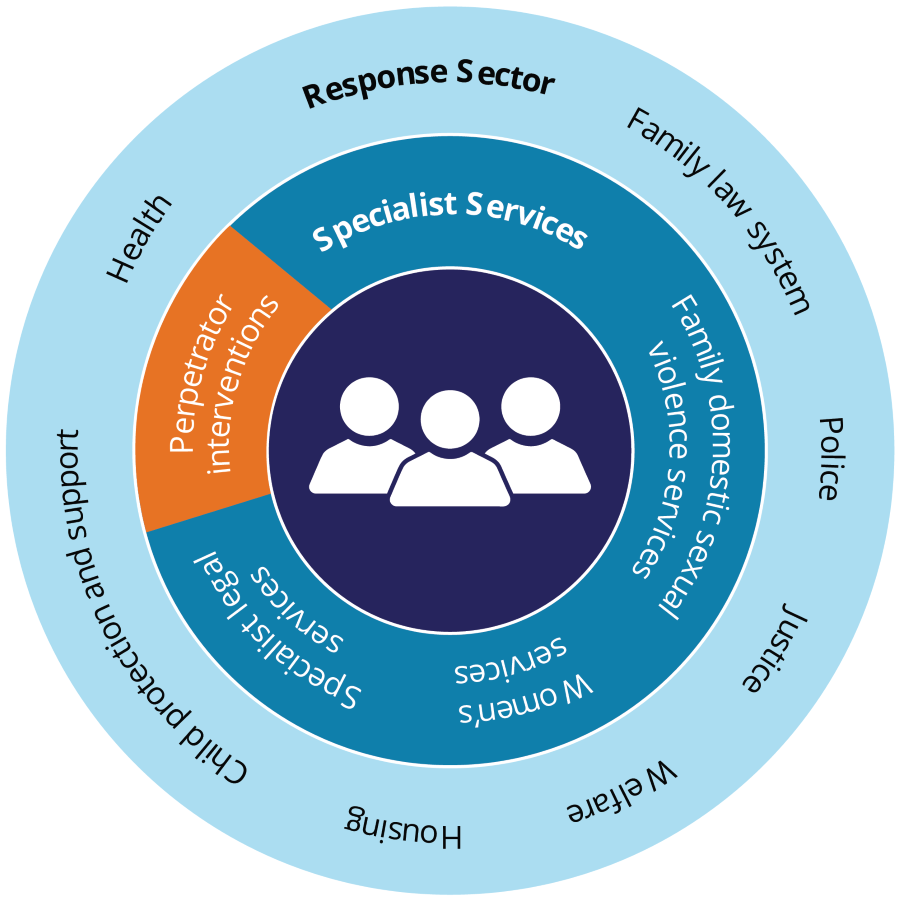

Perpetrator interventions are part of the system of services responding to FDSV – an overlapping system of services and service providers that respond to violence. While many service providers may come into contact with people who use violence, a subset of these service providers have a specialised role in stopping violence once it has occurred and holding perpetrators to account for their behaviour. These service providers work with perpetrators and people who use violence (Box 1).

The term perpetrator is used to describe adults (aged 18 years and over) who use violence, while ‘people who use violence’ is a broader, more inclusive term that extends to children and young people who use violence.

On this page, the term ‘perpetrator interventions’ is used, as the focus is on interventions for adult perpetrators, who have used violence against other adults. Other specialist interventions – such as those for young people who use violence, or those that intervene to stop offenders of child sexual abuse – require more consideration and are not discussed in detail here. A more detailed discussion about the language used to describe people who use violence can be found in Who uses violence?

‘Perpetrator interventions’ captures a broad range of services and service providers that work with people who use violence. The term ‘perpetrator interventions’ is used for simplicity, as it is the most commonly used term to describe this category of services.

Perpetrator interventions are diverse, and span multiple sectors. Perpetrator interventions work alongside other services responding to FDSV, to end violence and keep people and communities safe (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Perpetrator interventions

In general, there are 2 types of interventions for perpetrators: behaviour change interventions (often referred to as men’s behaviour change programs), and police and legal responses. The term ‘responses’ is used to refer to the services and service providers that play a role in assisting people when violence has occurred.

On this topic page, behaviour change interventions are referred to as ‘specialist perpetrator interventions’ to distinguish them from police and legal responses. These interventions work within the broader service system – as well as with the community – to hold perpetrators to account.

What does perpetrator accountability mean to you?

'Perpetrator accountability describes the process of perpetrators, as individuals and as a collective, being visible and taking responsibility for their use of family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV). Perpetrator accountability includes service systems holding perpetrators accountable and ensuring that the impact of their responses is not complicit in, nor perpetuates, FDSV.'

Leanne

'Perpetrator accountability means framing the issues of family, domestic, and sexual violence as fundamentally a problem of perpetration. It is the perpetrator’s behaviour that should be scrutinised and questioned – not just by systems and institutions, but by friends, family, peers, employers, and community members. It is the perpetrator’s behaviour and use of abuse that needs to change.'

Lula

Perpetrators may also interact with health services, alcohol and other drug treatment services, specialist homelessness services (see Housing) and other human services that deal with issues that may be related to the use of FDSV. These services comprise the broader service system, but are not included on this topic page as they may not necessarily be purpose-built to intervene with violence. A discussion about how services work together to respond to FDSV can be found in Services responding to FDSV.

Not all responses to FDSV occur within the service system. Some responses are informal, and involve seeking support from families and friends. Those are discussed in more detail in How do people respond to FDSV?

Men’s Behaviour Change Programs

Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCPs) are the most common interventions for people who use violence (AIHW 2021). MBCPs vary substantially in how they operate, how they are accessed, and the legislative frameworks that they operate under. Some MBCPs are available to those who self-refer or are concerned about their own behaviours. Perpetrators can also be required to attend programs, either informally by their partners or communities, or formally through courts or corrective services (AIHW 2021).

Across MBCPs in Australia, there is a large variation in the approach adopted and the mode used to administer the program. Bell and Coates’ (2022) systematic review found that behaviour change programs can be informed by:

- the Duluth model, which uses a psychoeducational and feminist approach

- psychological models such as cognitive behaviour therapy or motivational approaches

- anger management or substance use treatment.

Further, the mode of delivery can also vary. Some programs last as long as a year, while others are much shorter. Some programs also offer individual case management, while others are limited to group work only (Bell and Coates 2022).

Legal and police responses

In addition to behaviour change interventions, legal and police services intervene directly with perpetrators who use violence. Some common legal and police responses to FDSV include: protection orders; arrests and criminal charges; and prosecution and sentencing in criminal courts. These responses are discussed in Legal systems, FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police.

What do the data show?

No single data source is available to report on specialist perpetrator interventions in Australia. However, some data are available from specific organisations to look at service use. For example, the No to Violence Annual Report (see Data sources and technical notes).

Men’s Referral Service

The Men’s Referral Service provides support for men who have used or continue to use violence and who are seeking support to change their abusive behaviours.

In 2021–22 the Men’s Referral Service responded to 7,600 inbound calls from people seeking support related to men’s family violence. There was an increase of 61% in people seeking men’s family violence support via the webchat.

Men’s Referral Service also receive referrals from police in selected states and territories. Almost 60,000 referrals were received from police in New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania. Police referrals increased by 2.8% from 2020–21, with the biggest increase coming from New South Wales (up from 34,500 in 2020–21 to 38,000 in 2021–22) (No To Violence 2022).

Men’s Referral Service counsellors also facilitate the Brief Intervention Service (BIS), a flexible, multi-session service designed to provide counselling support and referral options to men as they begin the behaviour change journey. BIS focuses on short term multi-session counselling and support for men who have not yet accessed a behaviour change program.

Just over 500 men engaged with the Brief Intervention Service during 2021–22, for an average of 6 sessions (No To Violence 2022).

To see information about other helplines responding to FDSV, see Helplines and related support services.

What else do we know?

There has been valuable work to build the evidence base on perpetrator interventions through research into what currently works to stop violence.

‘What Works’ to reduce and respond to violence against women

Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety’s (ANROWS) ‘What Works’ project provided a framework to support the assessment of the overall value and effectiveness of FDSV interventions, programs and strategies. The aim was to develop:

- an evidence portal/What Works framework that allows comparison of practices and that provides a summary of the evidence base of what works to reduce or respond to violence against women

- accessible and practical information about the applicability of interventions, as well as information about the implementation

- directions for future research, including suggestions in terms of research design and recommendations around the measurement of outcomes.

As part of the ‘What Works’ framework, ANROWS developed 3 overviews:

- Reducing relationship and sexual violence, which provides an overview of the evidence from systematic reviews of respectful relationships programs and bystander programs in education settings.

- The effectiveness of interventions for perpetrators of domestic and family violence, which provides an overview of the evidence in relation to 2 key types of interventions for perpetrators: behaviour change interventions, and legal and policing interventions.

- The effectiveness of crisis and post-crisis responses for victims and survivors of sexual violence, which assesses the evidence from existing systemic reviews into the effectiveness of crisis and post-crisis interventions for victim-survivors of sexual violence.

This work demonstrates the value of consolidating information on perpetrator interventions and services to understand the extent to which evidence-based practices are implemented (Box 2).

Bell and Coates (2022) conducted a systematic review of 2 key intervention types for perpetrators of FDV and IPV: behaviour change interventions, and legal and policing interventions. Reviews across the international literature were included if they concerned high-income countries. Reviews limited to only low- or middle-income countries were excluded.

The aim of the review study was to provide an overview of the evidence on effectiveness as reported by reviews of interventions for perpetrators of FDV. The study found:

- Of 29 reviews that assessed the effectiveness of behaviour change interventions for a reduction in FDV/IPV, only one concluded that the intervention works.

- A total of 24 reviews reported on the impact of behaviour change interventions on perpetrator-specific outcomes. While some reviews reported promising results such as improvements in gender-based attitudes, reduced acceptance of violence, improved mental health outcomes or a reduction in substance misuse, most reported mixed findings and concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence.

- Effectiveness was found to be associated with a range of factors, most commonly treatment modality for behaviour change interventions and perpetrator characteristics such as previous history of offending for legal and policing interventions. Albeit based on a smaller evidence base, interventions that included substance use treatment and motivational enhancement or readiness for change approaches were associated with more promising results than Duluth or cognitive behaviour change-based interventions.

More information about this stream of work can be found on the ANROWS website, at ‘What Works’ to reduce and respond to violence against women.

Monitoring perpetrator interventions

One way to understand whether perpetrator interventions are effective, is to monitor progress over time. Under the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and Children 2010–2022 (completed), the National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions (NOSPI) were developed to guide and measure the actions taken to intervene with perpetrators (Box 3).

The National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions (NOSPI) were developed as a set of headline standards, or principles, to guide and measure the actions that governments and community partners take to intervene with perpetrators of FDSV, and the outcomes achieved by these actions. The following six headline standards were agreed by the former Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in 2015:

- Women and their children’s safety is the core priority of all perpetrator interventions.

- Perpetrators get the right interventions at the right time.

- Perpetrators face justice and legal consequences when they commit violence.

- Perpetrators participate in programmes and services that change their violent behaviours and attitudes.

- Perpetrator interventions are driven by credible evidence to continuously improve.

- People working in perpetrator intervention systems are skilled in responding to the dynamics and impacts of domestic, family and sexual violence.

In collaboration with states and territories, a reporting framework was developed with 27 key indicators to measure the 6 headline standards. Where data were not available, indicators were developed as aspirational, to guide data development activities (AIHW 2021).

Limitations

The AIHW undertook work to collect and report data against the 27 indicators. This work highlighted some barriers to data collection and reporting:

- perpetrator interventions are fragmented and multi-sectoral

- data are not comparable between states and territories

- data on specific population groups are limited.

While data were not available to report comprehensively against the NOSPI, the NOSPI reporting work highlighted the initiatives underway in states and territories to respond to perpetrators. Further data improvement is required before nationally comparable indicators are possible. For more information, see Monitoring Perpetrator Interventions in Australia.

Data gaps and development activities

While specialist perpetrator interventions remain a data gap, there are areas in which data improvements can help shed light on how people who use violence may interact with the service system when violence occurs.

Specialist FDV services data

At a national level there are very limited data from specialist family and domestic violence services, which include things like crisis services. The AIHW is leading the delivery of a prototype specialist FDV services data collection, which will inform recommendations for an ongoing national specialist services data collection which could be expanded and built on in the future. Improved data on specialist services could potentially be a valuable source of information about related perpetrator services, including pathways and referrals into perpetrator intervention services.

Improving data on behaviour change programs

In 2019, ANROWS undertook a study into developing a minimum data set for Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCPs) in Australia. A minimum data set would fill a critical gap in the perpetrator interventions landscape (Box 4).

Currently, there is no uniform data collection and management tool in Australia to collect data from MBCPs. In 2020, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) published findings from their work, which looked into building a minimum data set that aimed to address this data gap. The study focused on key variables related to participants’ demographic characteristics, recidivism, and attrition and retention in MBCPs.

The study involved the development of a survey for service providers, which asked questions about key variables to understand:

- if the item was collected or collated

- the frequency of data collection

- and the perceived importance of individual variables being included in a data collection.

The study concluded that the implementation of a national minimum data set across all MBCPs in Australia would be highly valuable in confirming variables predicting program attrition, and consequently could help determine MBCP suitability for certain types of perpetrators. Study results suggest that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ structure of mainstream national MBCPs is not the best approach, and further development of a data set could allow for MBCPs to be adapted and diversified to improve their effectiveness (Chung et al 2020).

More information about this work can be seen in the ANROWS’ report Improved accountability – the role of perpetrator intervention systems.

Linked data

The National Crime and Justice Data Linkage Project aims to link administrative datasets from across the criminal justice sector, including police, criminal courts and corrective services, forming the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Criminal Justice Data Asset. Once fully established, this data asset could provide insight on how perpetrators of family and domestic violence move through the criminal justice sector, including corrective service outcomes for FDSV offenders. In the future, other health and welfare datasets could also be included to provide a more holistic view of perpetrators, and potentially, victim-survivors.

A more general discussion about data gaps and development activities can be found in Key information gaps and development activities.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) Monitoring perpetrator interventions in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 November 2022. doi:10.25816/px2h-ek26

Bell C and Coates D (2022) ‘The effectiveness of interventions for perpetrators of domestic and family violence: An overview of findings from reviews’, ANROWS Research Report WW.22.02/1.

Chung D, Upton-Davis K, Cordier R, Campbell E, Wong T, Salter M, Austen S, O’Leary P, Breckenridge J, Vlais R, Green D, Pracilio A, Young A, Gore A, Watts L, Wilkes-Gillan S, Speyer R, Mahoney N, Anderson, S and Bissett, T (2020), ‘Improved accountability: The role of perpetrator intervention systems’, ANROWS Research Report 20/2020.

No To Violence (2022) Annual Report 2021–2022, accessed 6 December 2022.

- Previous page Financial support and workplace responses

- Next page FDSV workforce