Older clients

On this page

Key findings: Older clients, 2022–23

Australia’s homeless population is ageing and there is a growing homelessness problem among Australia’s ageing population. In 2006, about 12,500 people experiencing homelessness were aged 55 or older (or 14% of people experiencing homelessness), increasing to about 14,600 in 2011, 18,700 in 2016, and 19,400 people in 2021 (or 16% of people experiencing homelessness) (ABS 2012, 2018, 2023).

The lack of affordable housing in recent times has left many Australians at risk of homelessness. Older Australians have increasingly experienced rental stress, amid the increasing costs of housing and renting across Australia. Around one per cent of rental listings in Australia were considered affordable (rent costs less than 30% of their income) for a single person or couples on the age pension (Anglicare Australia 2023, AIHW 2023). Although Commonwealth Rent Assistance assists many older people with the costs of renting, about 2 in 5 older people receiving this payment were considered to be in rental stress (AIHW 2023). Without affordable housing, many more older Australians may be at risk of or experience homelessness.

Homelessness can be a recurring or persistent feature among some older people’s lives. Some may experience repeat homelessness later in life, while others remain homeless as they age (Petersen et al. 2014). For these older people, lifelong struggles and negative experiences, such as mental health issues, addiction, and prison time were often common to their pathways into homelessness (Petersen et al. 2014).

For other older people, their lives were fairly ‘conventional’, with many raising families and working (typically low paid) for most of their lives (Petersen et al. 2014). Among these older people (often older women), a major disruption – such as the breakdown of a marriage, loss of a job, the death of a partner or the development of an illness – together with a lack of savings led them toward their very first experience of homelessness (Canham et al. 2021, Kushel 2020).

Although homelessness is traumatising for all who experience it, experiencing homelessness in later life poses additional health risks and challenges (Scutella et al. 2014). The harsh living conditions and reduced access to healthcare that often comes with homelessness can either trigger or exacerbate health problems (Parsell et al. 2018). Older people experiencing homelessness are not only more likely to live with more disabilities, chronic diseases, complex health problems and geriatric symptoms but also die earlier (Canham et al. 2020, Humphries and Canham 2021, Nilsson et al. 2018). Furthermore, these health issues occur at a higher frequency amongst older people and are often accompanied by other mental and physical impairments, requiring specialised services to provide adequate care. As these services can be quite limited, addressing some core aspects of homelessness amongst older Australians can be challenging (Om et al. 2022, Nilsson et al. 2018, O’Connor et al. 2023).

Older people aged 55 and older who received assistance from SHS at some point between July 2014 to June 2017 were less likely to require services from SHS overall, when compared to SHS clients aged 54 and under (AIHW 2022). Older clients also tend to have relatively fewer vulnerabilities, and were less prone to homelessness (AIHW 2022).

Older SHS clients are defined as clients aged 55 years and over. For further information, see Technical notes.

Older women

The experience of homelessness has become increasingly widespread among older women, growing by almost 40% between 2011 and 2021 to about 7,300 older women (ABS 2012, ABS 2023). While the shortage of affordable housing and the ageing population has contributed to the rising number of older people experiencing homelessness generally, lower lifetime earnings and savings is especially relevant to many older women’s experiences of homelessness. Given women are more likely to take leave from the workforce and return to paid employment on a part-time or casual basis, the amount of wealth accumulated is generally lower compared to men (Cameron 2013, Power et al. 2018).

Client characteristics

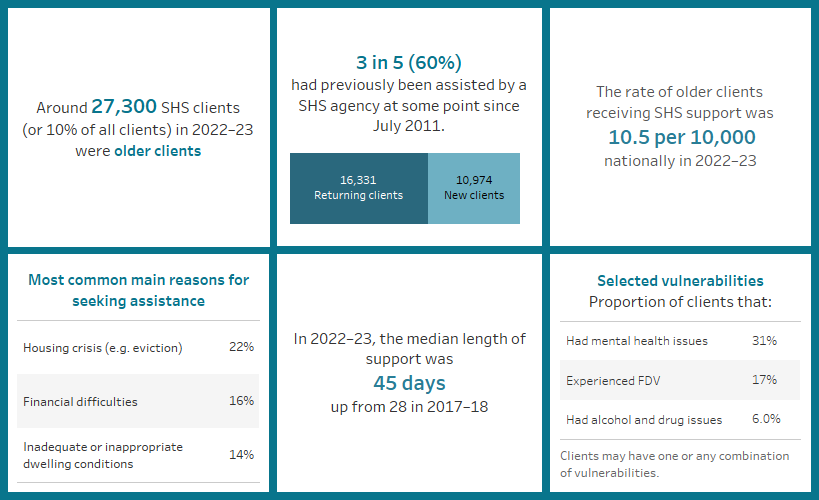

Figure OLDER.1: Key demographics, older SHS clients, 2022–23’

This interactive image describes the characteristics of around 27,300 older clients who received SHS support in 2022–23. Most were female, aged 55–64. Around one fifth were Indigenous. Victoria had the greatest number of clients and the Northern Territory had the highest rate of clients per 10,000 population. The majority of clients had previously been assisted by a SHS agency since July 2011. Most were at risk of homelessness at the start of support. Most were in major cities.

The number of clients aged 55 and over has risen by 13,000 clients in the 11 years to 2022–23, from 14,300 clients in 2011–12 to 27,300 clients in 2022–23 (Historical table HIST.OLDER).

In 2022–23 (Historical table HIST.OLDER):

- Older clients accounted for around 1 in 10 (10%) of all SHS clients. The proportion of older clients has been growing slowly since the collection began in 2011.

- The rate of older clients has increased from 6.4 clients for every 10,000 people in 2011–12 to 10.5 in 2022–23.

Labour force

Almost all older clients (93%) were not working in a paid job in 2022–23 (Supplementary table OLDER.7). There were more clients not in the labour force (12,100 clients, or 51%) than unemployed (10,100, or 42%). Around 3 times as many older clients who were unemployed were aged under 65 (7,500 clients), compared to those 65 or older (2,600).

Living arrangements

In 2022–23, of the almost 25,500 older clients with known living arrangement upon presentation to a SHS agency (Supplementary table CLIENTS.45):

- Most (16,000 clients) were living alone; higher for males (72% of older male clients) than females (54%).

- Around 1 in 10 (12% or 3,100 clients) were living with other family.

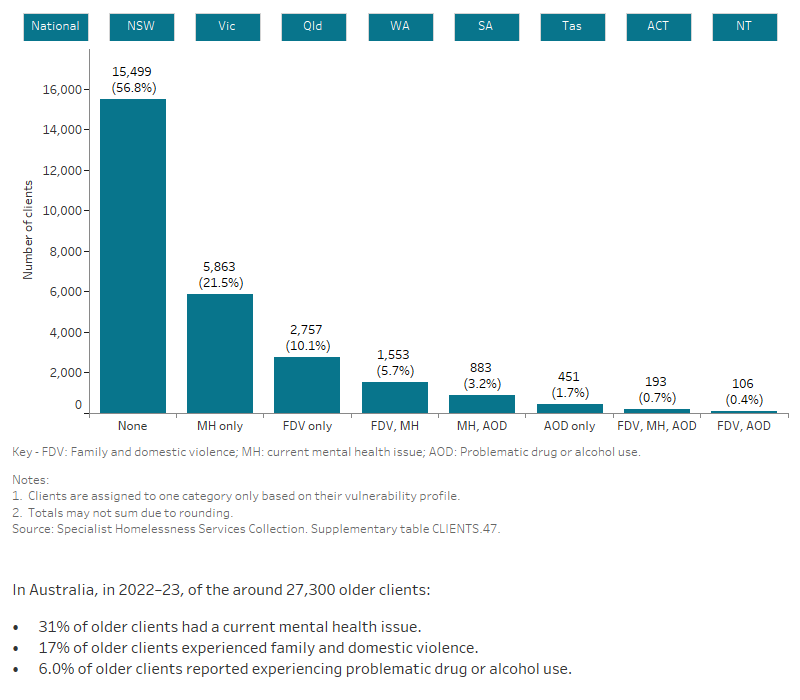

Selected vulnerabilities

The majority of older clients (57% or 15,500) did not have additional vulnerabilities that may contribute to the risk of experiencing homelessness, such as a current mental health issue, experiencing family and domestic violence, or problematic drug and/or alcohol use (Figure OLDER.2, Supplementary table CLIENTS.47).

Figure OLDER.2: Older clients, by selected vulnerability characteristics, 2022–23

This interactive bar graph shows the number of older clients also experiencing additional vulnerabilities, including family and domestic violence, having a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use. The graph shows both the number of clients who experiencing a single vulnerability only, as well as combinations of vulnerabilities, and presents data for each state and territory.

Service use patterns

The length of support older clients received increased in 2022–23 to a median of 45 days, up from 28 days in 2017–18. The average number of support periods per client, however, was stable at 1.6 support periods per client over time. The median number of nights accommodated decreased to 26 nights from 29 nights in 2017–18 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.48).

New or returning clients

Around 60% (or 16,300 clients) of older SHS clients were returning clients – having been assisted by a SHS agency before (since the collection began in July 2011) – one of the lowest proportions among any SHS client group (Supplementary table CLIENTS.42). Most returning clients (67%) were aged 55–64. Of new clients, 56% were aged 55–64.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

The top 3 main reasons older clients sought assistance from SHS agencies in 2022–23 were (Supplementary table OLDER.5):

- housing crisis (22% or 6,000 clients)

- financial difficulties (16% or 4,300)

- Inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (14% or 3,700).

The main reason older clients sought assistance was different for those experiencing homelessness compared with those presenting to services at risk of homelessness (Supplementary table OLDER.6).

- For those experiencing homelessness the main reasons for seeking assistance were:

- housing crisis (24% or over 2,300 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (23% or 2,200)

- housing affordability stress (11% or 1,100).

- For those at risk of homelessness:

- housing crisis (23% or 3,600 clients)

- financial difficulties (18% or 2,700)

- family and domestic violence (12% or 1,800).

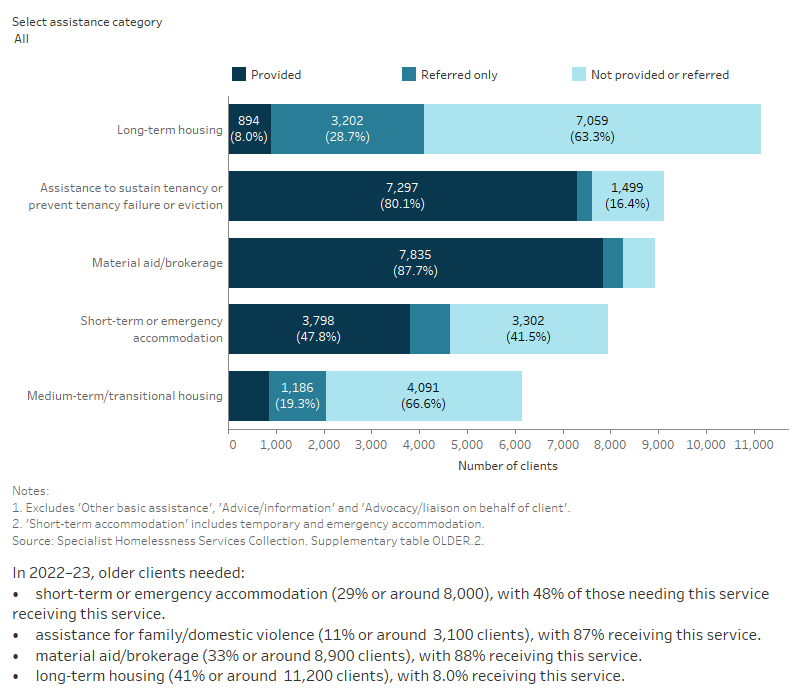

Services needed and provided

In 2022–23, over half (53% or 14,500) of older SHS clients needed accommodation; 36% of these clients were provided with some type of accommodation assistance and 21% were referred to another agency for this type of support. Need was highest for long-term accommodation (41% or 11,200 needed long-term accommodation), though only 8.0% of older clients who needed it received it. By contrast, of the quarter (29%) of older clients who needed short-term accommodation, almost half (48%) received it (Figure OLDER.3, Supplementary table OLDER.2).

Other services most commonly needed by older clients during 2022–23 were:

- assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction (33%), with 80% provided this assistance

- material aid/brokerage (33%), with 88% provided this assistance

- financial information (18%), with 82% provided with assistance.

Figure OLDER.3: Older clients, by services needed and provided, 2022–23

This interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the services needed by older clients and their provision status. Long-term housing was the most needed service but the least provided service. Material aid/brokerage was the most provided service.

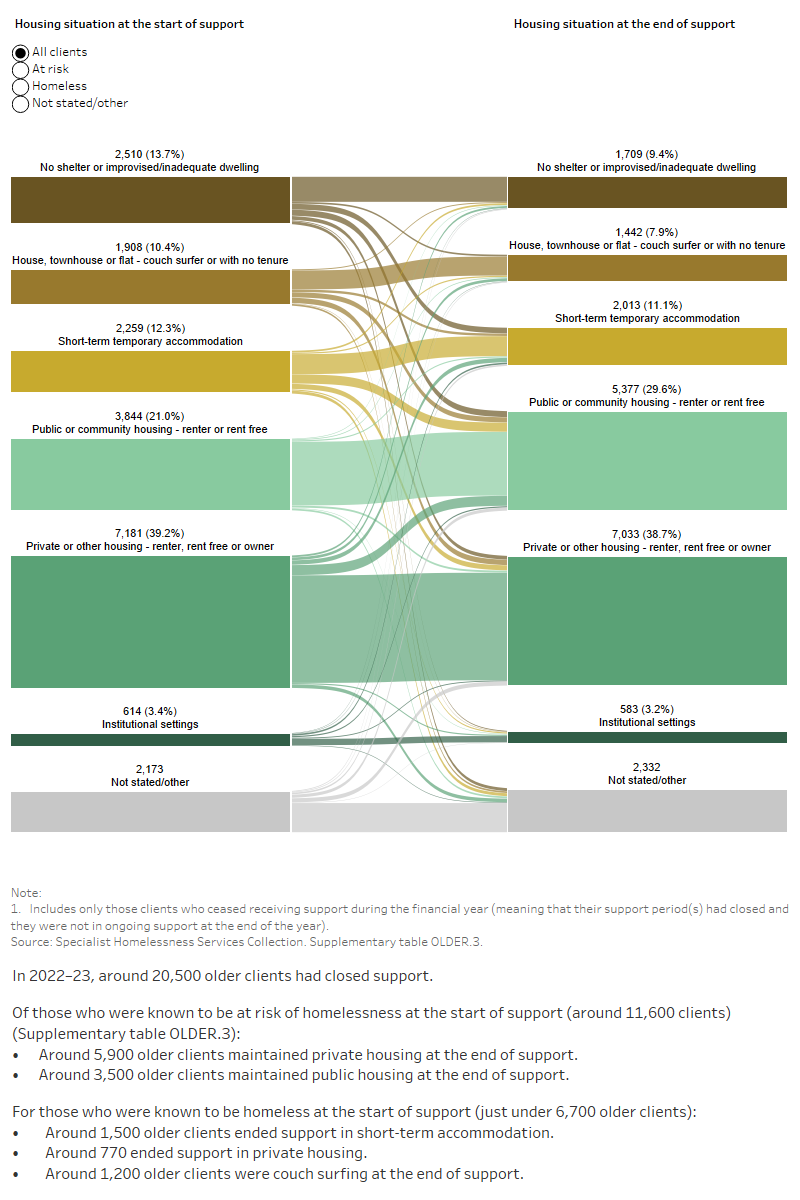

Housing situation and outcomes

Outcomes presented here highlight the changes in clients’ housing situation at the start and end of support. That is, the place they were residing before and after they were supported by a SHS agency. The information presented is limited only to the clients who have stopped receiving support during the financial year, and who are no longer receiving ongoing support from a SHS agency. In particular, information on client housing situations at the start of their first period of support during 2022–23 is compared with the end of their last period of support in 2022–23. As such, this information does not cover any changes to their housing situation during their support period.

More than one-third (36% or 6,700 clients) of older clients were experiencing homelessness at the start of support; 2,500 (14%) had no shelter or were in an improvised/inadequate dwelling and 2,300 (12%) were in short-term temporary accommodation (Supplementary table OLDER.3).

By the end of support, fewer older clients were known to be experiencing homelessness (28%). Instead, most older clients (72%) were living in stable accommodation by the end of support in 2022–23, be it public or community housing, private or other housing or an institutional setting (Supplementary table OLDER.4).

Figure OLDER.4: Housing situation for older clients with closed support, 2022–23

This interactive Sankey diagram shows the housing situation (including rough sleeping, couch surfing, short-term accommodation, public/community housing, private housing and Institutional settings) of older clients with closed support periods at first presentation and at the end of support. The diagram shows clients’ housing situation journey from start to end of support. Most clients started and ended support in private housing.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Census of Population and Housing: estimating homelessness, 2006. ABS website, accessed 10 October 2022.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) Census of Population and Housing: estimating homelessness, 2011, ABS website, accessed 27 July 2023.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023) Census of Population and Housing: estimating homelessness, 2021, ABS website, accessed 27 July 2023.

Anglicare Australia (2023) Rental Affordability Snapshot, Anglicare website, accessed 25 July 2023.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Financial assistance 2023 [data set], AIHW website, accessed 07 October 2022.

AIHW (2022) Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Older clients in 2014–17, AIHW website.

Cameron P (2013) ‘What’s choice got to do with it? Women’s lifetime financial disadvantage and the superannuation gender pay gap’, Policy Brief No. 55, The Australia Institute. July 2013.

Canham SL, Humphries J, Moore P, Burns V and Mahmood A (2021) ‘Shelter/housing options, supports and interventions for older people experiencing homelessness’, Ageing and Society, 4(1):1-27, doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21000234.

Canham SL, Custodio K, Mauboules C, Good C and Bosma H (2020) ‘Health and psychosocial needs of older adults who are experiencing homelessness following hospital discharge’, The Gerontologist, 60(4): 715-724, doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz078.

Humphries J and Canham SL (2021) ‘Conceptualizing the shelter and housing needs and solutions of homeless older adults’, Housing Studies, 36(2):157-179, doi: 10.1080/02673037.2019.1687854.

Kushel M (2020) ‘Homelessness among older adults: An emerging crisis’, Generations, 44(2):1-7.

Nilsson SF, Laursen TM, Hjorthøj C and Nordentoft M (2018) ‘Homelessness as a predictor of mortality: an 11-year register-based cohort study’, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(1):63-75. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1456-z.

Om P, Whitehead L, Vafeas C and Towell-Barnard A (2022) ‘A qualitative systematic review on the experiences of homelessness among older adults’, BMC geriatrics, 22(1):1-10, doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02978-9.

O‘Connor CMC, Poulos RG, Sharma A, Preti C, Reynolds NL, Rowlands AC, Flakelar K, Ragus A, Valpiani P, Faux SG, Boyer M, Close JCT, Gupta L, Poulos CJ (2023) ‘An Australian aged care home for people subject to homelessness: health, wellbeing and cost-benefit’, BMC Geriatr, 23(1): 253, doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-03920-3

Parsell C, Ten Have C, Denton M, Walter Z (2018) ’Self-management of health care: multimethod study of using integrated health care and supportive housing to address systematic barriers for people experiencing homelessness’, Australian Health Review, 42(3):303-308, doi: 10.1071/AH16277.

Petersen M, Parsell C, Phillips R, White G (2014) ‘Preventing first time homelessness amongst older Australians’, AHURI Final Report No. 322, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

Power E, Mee K and Horrocks J (2018) ‘Housing: An infrastructure of care for older Australians’, Parity, 31 (4): 16-18, doi: 10.3316/informit.763478754874546.

Scutella R, Chigavazira A, Killackey E, Herault N, Johnson G, Moschion J and Wooden M (2014) ‘Findings from Waves 1 to 4: Special topics’, Journeys Home Research Report No. 4, report to the Australian Government Department of Social Services, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.