Nutrition

Why are rates on fruit and vegetable consumption important?

Nutrition is one of the most important behavioural risk factors on an individual’s health (AIHW 2015), and has significant potential to improve overall public health (NHMRC 2013). Poor nutrition can lead to increased risk of overweight and obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and some forms of cancer (AIHW 2015; NHMRC 2013).

For young people, a wide variety of nutritious foods is needed for achieving and sustaining normal growth and development (NHMRC 2013). Growth in height accelerates rapidly over 1–3 years in adolescence before ceasing at about 16 years in girls and 18 years in boys (NHMRC 2013). The development of healthy eating habits is particularly important during childhood and adolescence as these habits are likely to persist across the lifespan. However, this is subject to an increasing array of influences, including peer pressure, which peaks in adolescence (NHMRC 2013).

The evidence suggests that total fruit intake (including fruit juice) and whole fruit intake (whole fruit only) are the second and third most correlated factors with an overall healthy eating pattern, after amount of empty calories consumed (Guenther et al. 2007).

Dietary guidelines on fruit and vegetable consumption

The 2003 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC 2003) Dietary Guidelines for all Australians recommend the following serves of fruit and vegetables each day (ABS 2013):

For young people aged 12–17 years:

- Three serves of fruit

- Four serves of vegetables

For young people aged 18–24 years:

- Two serves of fruit

- Five serves of vegetables

The guidelines were revised in 2013; however, 2003 guidelines are used here to allow changes over time to be reported.

Do rates vary across population groups?

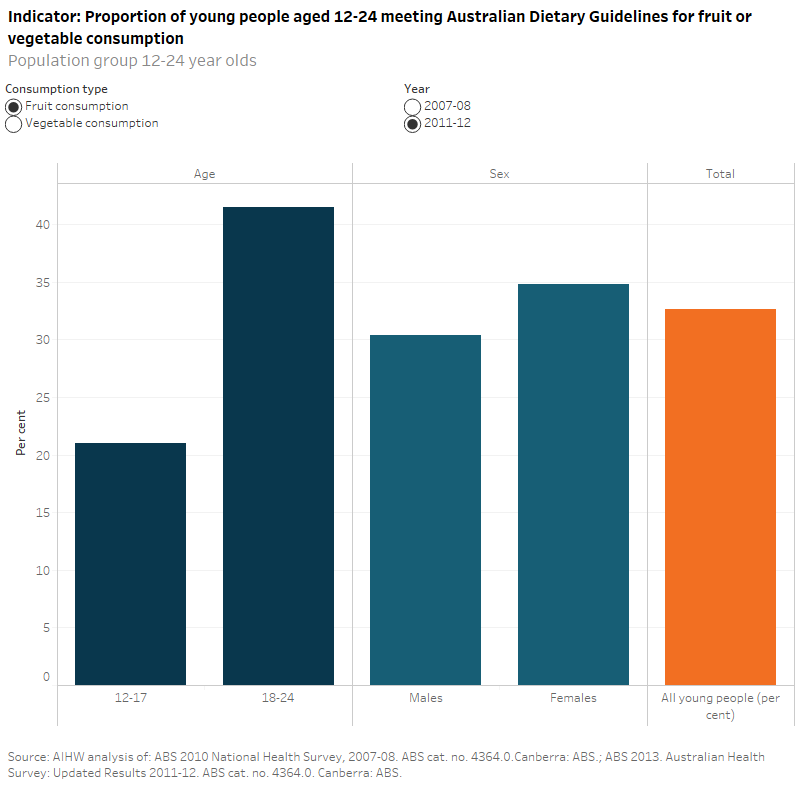

Fruit consumption

According to the Australian Health Survey 2011–12, about one in three (33%) young people aged 12–24 met the 2003 NHMRC guidelines on fruit consumption. About one in five (21%) young people aged 12–17 met the guidelines for their age, compared with around half the proportion of young people aged 18–24 year olds (42%). Fewer males than females met the fruit consumption guidelines (35% compared with 40%), although these were not statistically significant. Furthermore, the proportion of Indigenous young people aged 18–24 (39%) who met the guidelines was not significantly different to that of all young Australians aged 18–24 (42%).

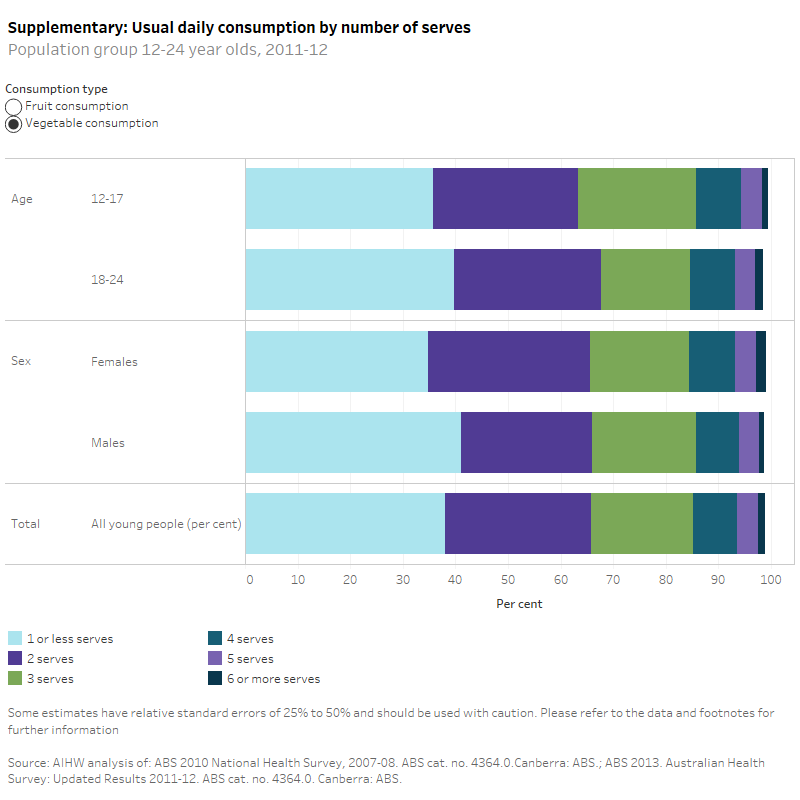

Vegetable consumption

In 2011–12, about one in seven (14%) young people aged 12–17 met the 2003 NHMRC guidelines on vegetable consumption which was more than double the proportion of young people aged 18–24 year olds (5.4%). Fewer males than females met the vegetable consumption guidelines (7.8% compared with 10.2%). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of Indigenous young people aged 18–24 who met the guidelines compared with all Australians from the same age cohort.

Has there been a change over time?

Fruit consumption

There has been no statistically significant change in proportion of young people (aged 12–24) meeting the fruit consumption guidelines between 2007–08 and 2011–12 (34% compared with 33%). There was also no statistically significant change for 12–17 year olds (around 21%) or the proportion of 18–24 year olds meeting the guidelines (45% to 42%).

Vegetable consumption

There has been a no significant change in the proportion of all young people (aged 12–24) meeting the vegetable consumption guidelines between 2007–08 and 2011–12 (10.3% compared with 9%). Similarly, the proportion of 12–17 year olds (16% to 14%) and 18–24 year olds (6% to 5.4%) meeting the guidelines has not changed significantly over this period.

Why don’t young people eat enough fruit and vegetables?

There are several reasons why young people may not be consuming sufficient fruit and vegetables for a healthy diet. There may be a lack of supply of fresh fruit and vegetables, particularly in very remote areas, and a lack of education about the importance of healthy eating or in food preparation techniques (AIHW 2015; Brimblecombe & O’Dea 2009). Healthy fresh foods are often more expensive than foods with poorer nutritional content and greater energy density (Darmon & Drewnowski 2008). Further, young people may be influenced by peer pressure or television advertising for foods with a high content of fat, sugar or salt (AIHW 2012; NHMRC 2013).

This report is based on survey data; relative standard errors and 95% confidence intervals are provided in the Source data tables: NYIF indicators. Some estimates have relative standard errors of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution. Significance testing was undertaken on values cited in the text; unless otherwise stated, differences were found to be statistically significant.

This report uses data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) 2007–08 National Health Survey and the ABS Australian Health Survey 2011–12 to report on the number of serves of fruit and vegetables consumed by young people. Using the NHMRC 2003 guidelines allows comparability between results for the 2011–12 Australian Health Survey and the 2007–08 National Health Survey.

AIHW analysis of: ABS 2010. National Health Survey, 2007–08. ABS cat. no. 4364.0. Canberra:ABS.; ABS 2013. Australian Health Survey: Updated Results 2011–12. ABS cat. no. 4364.0. Canberra:ABS.; ABS 2014. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Updated Results, 2012–2013. ABS cat. no. 4727.0. Canberra:ABS.

Data quality statements: Please refer to the published sources (above) for further information

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013. Profiles of Health, Australia, 2011–13: Daily intake of fruit and vegetables. Cat. no. 4338.0. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2012. Australia’s food and nutrition 2012. Cat. no. PHE 163. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease—Australian facts: Risk factors. Cardiovascular, diabetes and chronic kidney disease series no. 4. Cat. no. CDK 4. Canberra: AIHW.

Brimblecombe J & O'Dea K 2009. The role of energy cost in food choices for an Aboriginal population in northern Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 190(10):549–51.

Guenther P, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith S, Reeve B, Basiotis P 2007. Development and Evaluation of the Healthy Eating Index-2005: Technical Report. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, US Department of Agriculture.

NHMRC 2003. Dietary guidelines for all Australians. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.

NHMRC 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.