Child protection substantiations

Why are child protection substantiation rates important?

While most young people in Australia grow up in safe family environments, some experience maltreatment in the form of abuse and/or neglect. This can cause significant harm during childhood and adolescence, with the effects often continuing into adulthood (Lamont 2010a; Price-Robertson 2012). The adverse effects include poor physical health, attachment issues, reduced social skills, learning and developmental difficulties, mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance abuse, and a higher likelihood of criminal offending; (Gupta 2008; Lamont 2010b; Zolotor et al. 1999). A range of factors may place childen at higher risk of abuse and neglect. Young people are particularly vulnerable to harm in families experiencing multiple disadvantages, such as housing instability, poverty, low education, social isolation, neighbourhood disadvantage, parental substance misuse and mental health problems (Bromfield et al. 2010).

In response to the complex nature of child abuse and neglect, the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 was developed. The National Framework focuses on improving child safety and wellbeing through prevention, early intervention and best practice strategies, with an overarching goal of a substantial and sustained reduction in child abuse and neglect over time (COAG 2009).

What are child protection substantiations?

A substantiation of a child protection notification, refers to the conclusion, after investigation, that there is reasonable cause to believe that the child had been, was being, or was likely to be, abused, neglected or otherwise harmed. An appropriate level of continued involvement by the state or territory child protection and support services would then be made. This generally includes the provision of support services to the child and family. In situations where further intervention is required, the child may be placed on a care and protection order or in out-of-home care (see reports ’Care and protection orders’ and ‘Out-of-home care’ for more information).

Do rates vary across population groups?

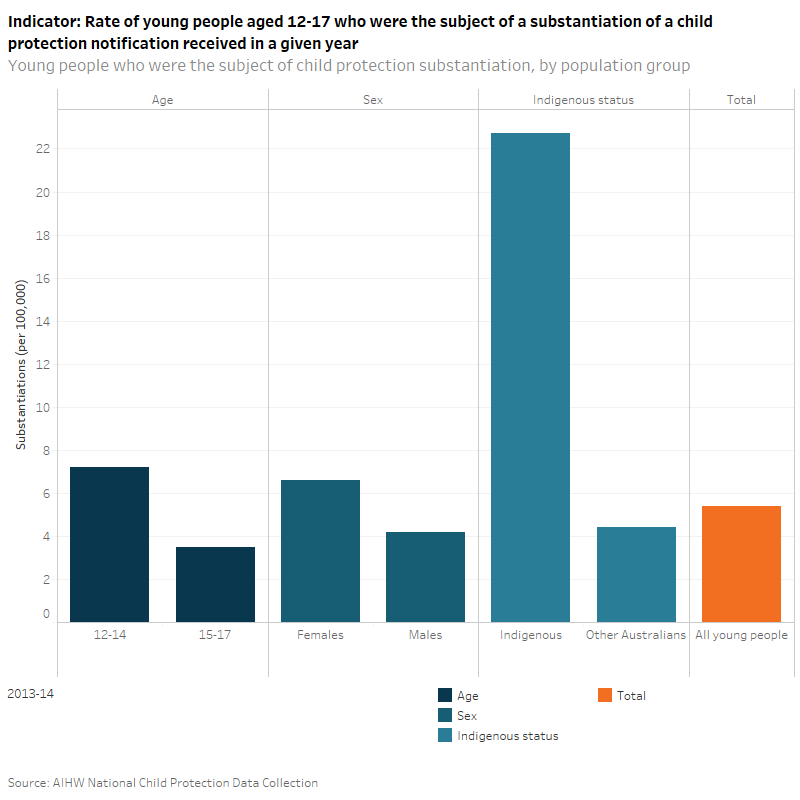

In 2013–14, in the AIHW Child Protection Data Collection, the national rate of young people aged 12–17 who were the subject of a child protection substantiation was 5.4 per 1,000 young people, with the rate lower among boys than girls (4.2 and 6.6 per 1,000 respectively). Young people aged 12–14 were more likely to be the subject of a substantiation (7.2 per 1,000 young people) compared with young people aged 15–17 (3.5 per 1,000 young people).

Indigenous young people were around 5 times as likely as Other Australian young people to be the subject of substantiated abuse or neglect (23 per 1,000 Indigenous young people compared with 4.4 per 1,000 Other Australians). The reasons for the over-representation of Indigenous young people in child protection substantiations are complex. The legacy of past policies of forced removal, intergenerational effects of previous separations from family and culture, lower socioeconomic status, and perceptions arising from cultural differences in child-rearing practices are all underlying causes for their over-representation in the child welfare system (HREOC 1997).

Has there been a change over time?

The national rate of young people in substantiations remained stable between 2009–2010 and 2010–11 at 4.5 per 1,000 young people. The rate then rose to 5.0 per 100,000 in 2011–12 and 5.5 per 100,000 in 2012–2013, and remained stable at 5.4 per 1,000 in 2013–14. For Indigenous young people, the rate has increased from 19 per 1,000 in 2009–10 to 23 per 1,000 in 2013–14. Although a real change in the incidence of abuse and neglect may contribute to the observed fluctuation, increased community awareness and changes to policy, practice and legislation in jurisdictions are also contributing factors (AIHW 2015).

What are the most common types of abuse?

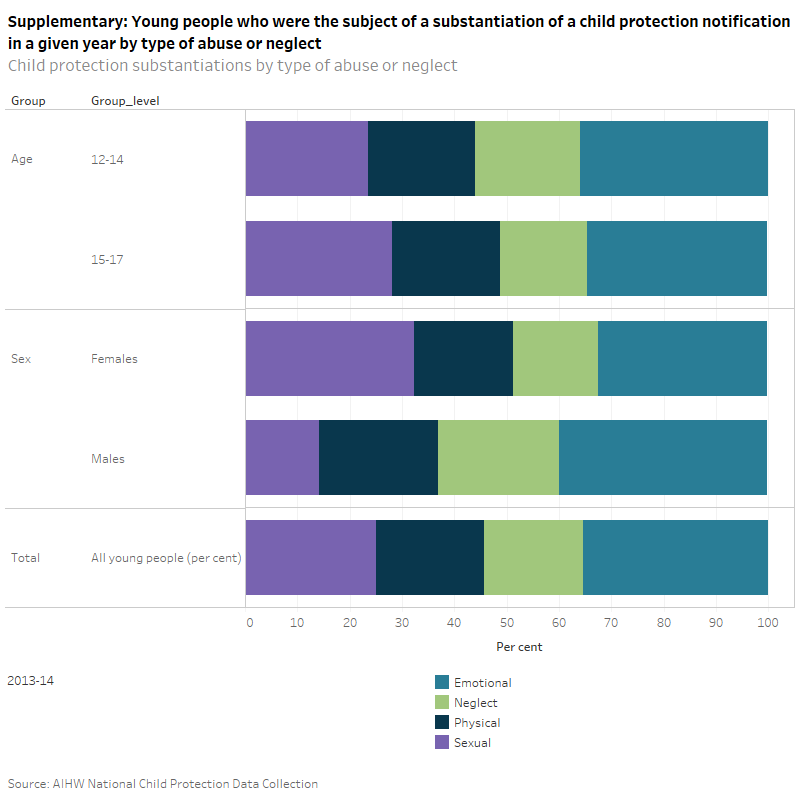

In 2013–14, emotional abuse was the most common form of abuse across all ages and across both genders. For both 12–14 year olds and 15–17 year olds, emotional abuse and sexual abuse were the most common forms. Emotional abuse was slightly higher in the younger age group compared with the older group (36% and 34% respectively) while sexual abuse was lower in the younger group compared with the older age group (24% and 28% respectively).

Overall a higher proportion of young males than females experienced emotional abuse (40% compared with 32%). A higher proportion of young males also experienced neglect compared with young females (23% and 16% respectively). Young females were twice as likely to experience sexual abuse as males (32% compared with 14%).

The true prevalence of child abuse and neglect across Australia is unknown because national child protection data are based on reported cases.

In Australia, child protection is the responsibility of state and territory governments. The AIHW collects and reports national data on child protection notifications, investigations, substantiations and other components of the child protection system. While the child protection systems and processes are broadly similar in each jurisdiction, child protection legislation, policies and practices vary. Therefore, caution needs to be taken when comparing child protection data across jurisdictions, or over time.

For data disaggregated by Indigenous status, ‘Other Australians’ includes non-Indigenous young people and young people for whom Indigenous status was unknown. In 2013–14, Indigenous status was unknown for around 3% of young people who were subject to child abuse substantiations.

From 2012-13, the Child Protection data collection reports unit record level data, which replaces the aggregate data previously used for national reporting. NSW and Queensland data for 2012–13 and 2013–14 were provided at aggregate level.

For more information on child protection processes and data, See Child protection Australia: 2013–14.

AIHW Child Protection Data Collection

Data quality statement: AIHW METeOR

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015. Child protection Australia: 2013–14. Child Welfare series no. 61. Cat. no. CWS 52. Canberra: AIHW.

Bromfield L, Lamont A, Parker R & Horsfall B 2010. Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems: the co-occurence of domestic violence, parental substance misuse, and mental health problems. National Child Protection Clearinghouse issues no. 33. Melbourne: AIFS.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) 2009. Protecting children in everyone’s business: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020. Canberra: COAG.

Gupta A 2008. Responses to child neglect. Community Care 1727:24–5.

Lamont A 2010a. Effects of child abuse and neglect for adult survivors. NCPC resource sheet, April 2010. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Lamont A 2010b. Effects of child abuse and neglect for children and adolescents. NCPC resource sheet, April 2010. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Price-Robertson R 2012. Fathers with a history of child sexual abuse: new findings for policy and practice. CFCA paper no. 6. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Zolotor A, Kotch J, Dufort V, Winsor J, Catellier D & Bou-Saada I 1999. School performance in a longitudinal cohort of children at risk of maltreatment. Maternal and Child Health Journal 3(1):19–27.