Seclusion and restraint in mental health care

Content warning

This report contains information some readers may find distressing as it refers to data about people who were legally compelled to receive mental health treatment.

On this page:

Seclusion is when a person is placed alone in a room and cannot leave by themselves. An example is a room with a door that locks and unlocks from the outside.

Restraint is when a person is held to stop them moving their body. Mechanical restraint is when items are used, such as tying belts or straps on their hands or arms. Physical restraint is when staff use their hands or body to stop a person moving freely.

This page shows data on the use of seclusion and restraint in Australian public hospital mental health care. Only acute units (providing short-term care) are covered.

Key points

In one year, Australian public hospital mental health care had:

10,851 seclusion events

1,522 mechanical restraint events

16,996 physical restraint events

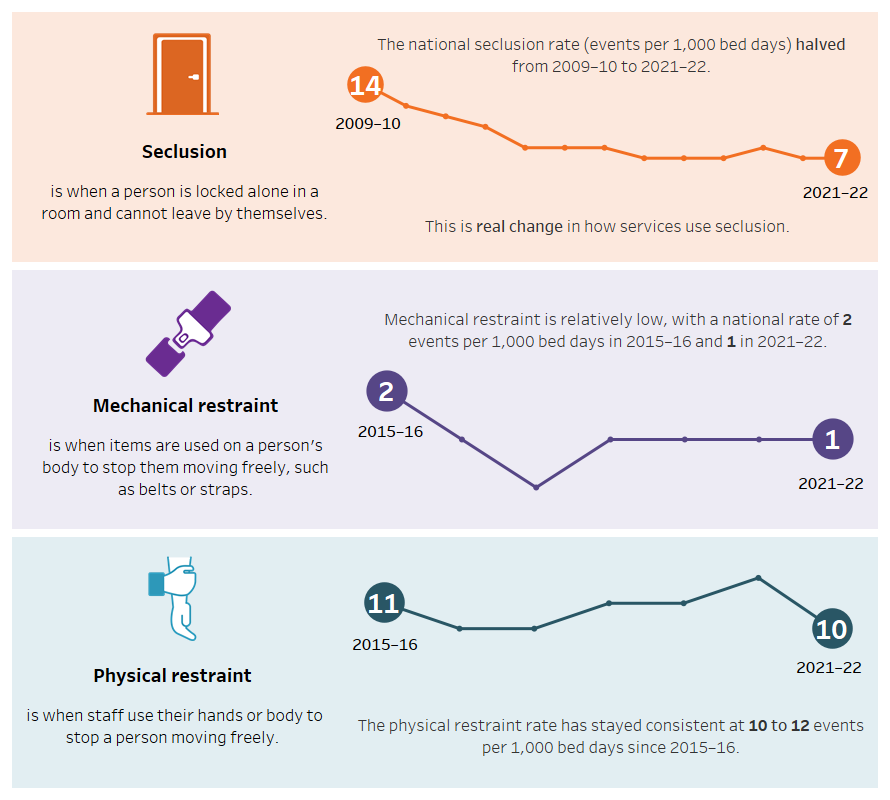

Three line graphs showing seclusion rate (events per 1,000 bed days) in Australia from 2009–10 to 2021–22 and mechanical and physical restraint rate from 2015–16 to 2021–22. Seclusion is the confinement of a person alone in a room and cannot leave by themselves. The national seclusion rate halved from 2009–10 to 2021–22. This is real change in how services use seclusion. Mechanical restraint is when items are used on a person’s body to stop them moving freely, such as belts or straps. Mechanical restraint is consistently low, with a national rate of 2 events per 1,000 bed days in 2015–16 and 1 in 2021–22. Physical restraint is when staff use their hands or body to stop a person moving freely. The physical restraint rate has stayed consistent at 10 to 12 events per 1,000 bed days since 2015–16. Refer to Tables 1 and 4.

Source: National Seclusion and Restraint Database, Tables SECREST.1 and 4.

In Australia, seclusion and restraint can be legally used in mental health care under some circumstances. All states and territories collect data on the use of seclusion and restraint in public acute mental health hospitals and provide data for national reporting every year.

Data on seclusion are available for over ten years.

- The national seclusion rate has halved over the last decade.

- People in acute hospital care were secluded 10,851 times during 2021–22, a rate of 7 events per 1,000 bed days.

- Seclusion lasted for 6 hours on average, excluding Forensic services (34 hours).

- Forensic services have had the highest rates of seclusion since 2016–17.

Data on restraint have been available for a shorter time than seclusion data.

- There were 16,996 physical restraint events and 1,522 mechanical restraint events during 2021–22, rates are 10 and 1 events per 1,000 bed days respectively.

- Forensic services have the highest rates of mechanical and physical restraint.

- Since data coverage began, the national physical restraint rate has not changed much. Mechanical restraint has a consistently lower rate.

Work towards establishing a national collection for seclusion data began in 2011 (Allan et al. 2017), with restraint data included a few years later. The collection and improvement of data on the use of seclusion and restraint in Australian mental health care is an ongoing initiative. Annual reporting continues through cooperative efforts in the mental health data sector, particularly with the coordinated efforts of state/territory mental health authorities and national government agencies.

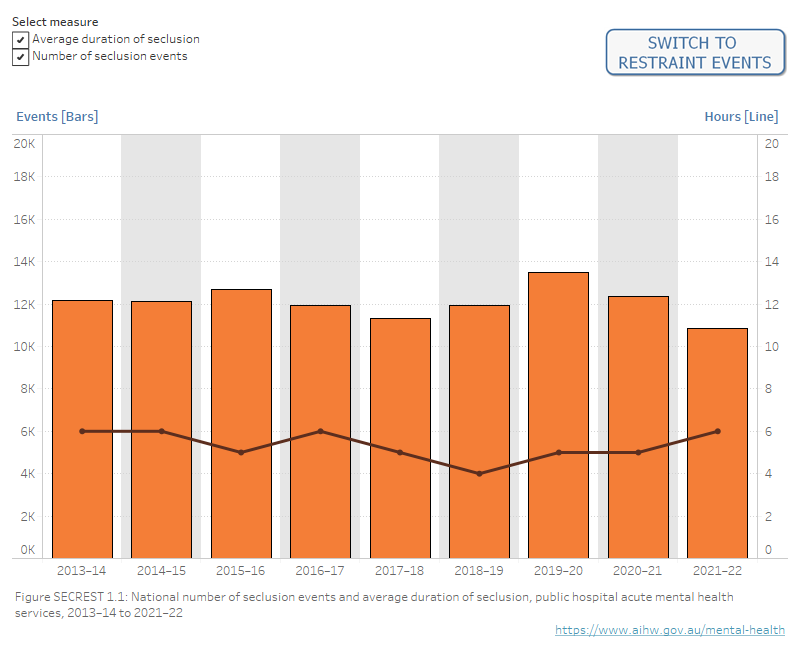

Figure 1 shows the number of times seclusion and restraint events were recorded in Australian public hospital mental health care during the last decade and how long seclusion lasted, on average.

Services can also be grouped by target population. Seclusion events that occurred in Forensic services had the longest average duration of 34 hours per seclusion event compared with the average of 6 hours (Table SECREST.2).

Figure SECREST.1.1. Bar graph showing the number of seclusion events in Australia from 2013–14 to 2021–22. A line overlaying the bars shows the average duration of seclusion in Australia for the same period. Refer to Table SECREST.1.

Figure SECREST.1.2. Bar graph showing the number of mechanical and physical restraint events in Australia from 2015–16 to 2021–22. Refer to Table SECREST.4.

Notes: Due to data comparability issues for events occurring in Forensic services, all Forensic service events are excluded from the average duration analysis.

Average duration of seclusion does not include South Australia prior to 2018–19. Queensland did not collect information on physical restraint events prior to 2017–18.

Source: National Seclusion and Restraint Database, Tables SECREST.1 and SECREST.4

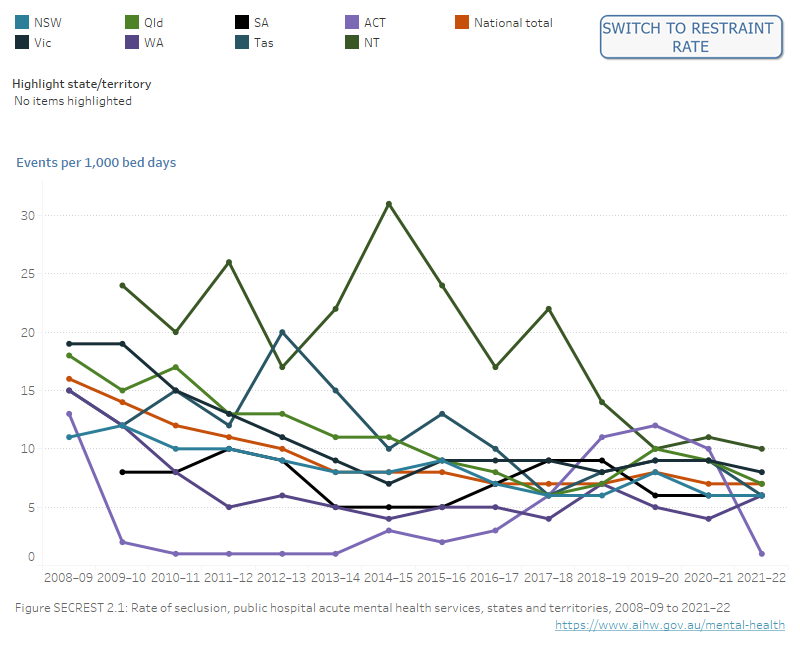

Figure 2 shows the rates of seclusion and restraint in Australian public hospital mental health care over time.

National rates

The national seclusion rate has halved since the first year of data collection for all states and territories from 14 per 1,000 bed days during 2009–10 to 7 during 2021–22. Over the last 5 years there has been little change to the national rate.

The national physical restraint rate has stayed about the same since data collection began, remaining between 10 and 12 since 2015–16. The national rate of mechanical restraint is consistently lower than physical restraint and has stayed at 1 during the last few years.

State and territory rates

Seclusion rates have decreased for all states and territories since the first year of data coverage.

- For 6 of the 8 states and territories, the rate of seclusion has better than halved during this period (since 2008–09 or 2009–10).

- Between 2020–21 and 2021–22, states and territories showed decreases or no change in the rate of seclusion, except Western Australia which reported an increase in the rate of seclusion from 4 to 6 events per 1,000 bed days.

Physical restraint rates decreased from the first year of data coverage for Victoria and Tasmania (since 2015–16).

- All other states and territories showed increases or little change.

- Between 2020–21 and 2021–22, physical restraint rates increased for Western Australia and South Australia while other jurisdictions had decreases or no change.

Mechanical restraint rates have been at 2 events per 1,000 bed days or lower for all states and territories since 2017–18.

- These rates have decreased or had little change from the first year of data coverage.

Figure SECREST.2: Rates of seclusion and restraint over time in Australian public hospital mental health care

Figure SECREST.2.1. Line graph showing seclusion events per 1,000 bed days for all states and territories from 2008–09 to 2021–22. There is an overall downward trend, with the exception of ACT. Refer to Table SECREST.1.

Figure SECREST.2.2. Line graph showing mechanical and physical restraint events per 1,000 bed days for all states and territories from 2015–16 to 2021–22. Mechanical restraint shows an overall downward trend, with the exception of NSW. Physical restraint shows an overall upward trend, with the exception of Vic where the rate has decreased over time. Refer to Table SECREST.4.

Notes: Rates are not calculated where numerators are less than 5 or denominators are less than 100 due to the potential for unreliable statistics.

Queensland did not collect information on physical restraint events prior to 2017–18. Comparisons between jurisdictions, between years, and for smaller jurisdictions should be undertaken with caution.

Source: National Seclusion and Restraint Database, Tables SECREST.1 and SECREST.4

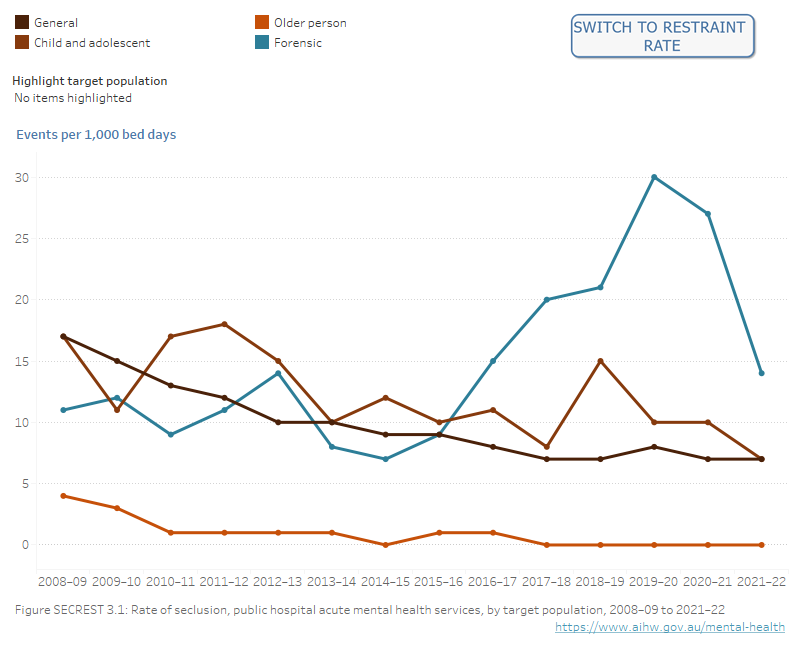

Seclusion and restraint data can also be presented by the target population of the service where the event occurred.

Figure 3 shows the rates of seclusion and restraint over time in Australian public hospital mental health care for general, child and adolescent, older person, and forensic target populations.

General services provide around three-quarters of care (77% of the total number of bed days in 2021–22).

Seclusion and restraint rates show:

- Forensic services had higher rates of seclusion, mechanical restraint and physical restraint than all other groups for the last six years.

- Child and adolescent services usually have higher rates of seclusion and physical restraint than General and Older person services.

Figure SECREST.3: Rates of seclusion and restraint over time by target population of Australian public hospital mental health care.

Figure SECREST.3.1. Line graph showing seclusion events per 1,000 bed days for General, Child and adolescent, Older persons, and Forensic target populations, from 2008–09 to 2021–22. Refer to Table SECREST.2.

Figure SECREST.3.2. Line graph showing mechanical and physical restraint events per 1,000 bed days for General, Child and adolescent, Older persons, and Forensic target populations, from 2015–16 to 2021–22. Refer to Table SECREST.5.

Note: Queensland did not collect information on physical restraint events prior to 2017–18.

Source: National Seclusion and Restraint Database, Tables SECREST.2 and SECREST.5

During 2021–22, hospitals located in Major cities and Outer regional and remote areas had a higher seclusion rate than Inner regional facilities (7 events per 1,000 bed days compared with 6). This has been a consistent pattern for the last three years. Seclusion in Major cities facilities were longer on average (7 hours) than other areas (Table SECREST.3).

During 2021–22, hospitals located in Major cities had a physical restraint rate of 11 events per 1,000 bed days, which was higher than for other areas. Rates of mechanical restraint were low for all areas (Table SECREST.6).

Seclusion and restraint during a hospital stay can have a negative impact on a person’s recovery.

Some people with mental illness and their carers advocate that restrictive practices do not benefit the consumer and that these interventions infringe on human rights, are anti-therapeutic and compromise the therapeutic relationship between the consumer and the clinician (Melbourne Social Equity Institute 2014; NMHCCF 2021).

Seclusion and restraint in mental health settings can affect everyone involved, including patients, carers and health care staff.

A person’s experience of seclusion or restraint can vary. Research in this area identifies a range of factors that can impact a person’s experience and long term effects on mental health care. Common ones are physical environment and the extent of consumer and carer engagement in the service.

The hospital’s physical environment can be a key component of the impact of seclusion and restraint.

Access to basic necessities such as food, warmth and the ability to go to the bathroom change a person’s physical comfort through the experience and potentially lessen trauma. Providing mental stimulation has also been suggested to lessen mental distress.

Based on the experience of consumers and staff (provided in group discussions, surveys and other methods), researchers have noted that the physical environment of a service (such as its design and layout of indoor and outdoor spaces) could be a factor in preventing seclusion and restraint from occurring. If a person is able to separate themselves from stressful environments when required, the need for a seclusion or restraint event is lessened.

Having the opportunity to access support from staff and family members throughout a person’s hospitalisation and in crisis situations, may also help in this regard.

Meaningful consumer engagement in service design and delivery can reduce the use and impact of seclusion and restraint.

Researchers and people with lived experience have described multiple ways for services and consumers to engage to improve service delivery and reduce seclusion and restraint. This can include:

- integrating the perspectives of people with lived experience in service planning

- including the consumer in decisions regarding their treatment

- having strategies in place for consumers at greater risk of becoming secluded or restrained

- use of reflective practice where consumers and staff are brought together to discuss an event of seclusion or restraint and create plans to avoid repeated use

- training with clinical and non-clinical staff (such as security personnel).

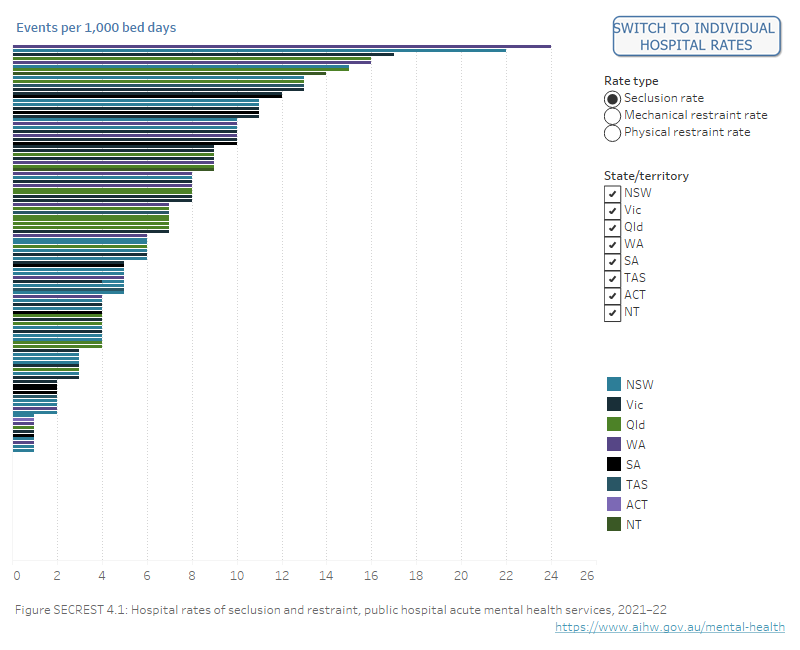

Figure 4 shows the rates of seclusion, mechanical restraint and physical restraint for Australian public hospital mental health care.

During 2021–22, the highest rates by hospital were 24 for seclusion, 14 for mechanical restraint and 80 for physical restraint. Of the 135 hospitals:

- 60% had a rate of zero for mechanical restraint (81 hospitals)

- 13% had a rate of zero for seclusion (17 hospitals)

- 7% had a rate of zero for physical restraint (9 hospitals).

Figure SECREST.4.1. Horizontal bar chart showing seclusion and mechanical and physical restraint events per 1,000 bed days in 2021–22 by hospital, excluding forensic units. Refer to Table SECREST.7.

Figure SECREST.4.2: Interactive text display showing seclusion and mechanical and physical restraint events per 1,000 bed days for each hospital in 2021–22. The user is able to select a particular hospital to display. Refer to Table SECREST.7.

Note: Due to data comparability issues for events occurring in Forensic services, all hospital level rates exclude Forensic services.

Source: National Seclusion and Restraint Database, Table SECREST.7

All Australian states and territories have legislation and associated regulations on the rights and treatment of people with mental illness in health care. Legislation varies between states and territories but all include criteria for when and where seclusion and restraint may be used.

Seclusion and/or restraint in health services can be used to provide safety and containment at times when this is considered necessary to protect patients, health service staff and others. However, use of these practices can also be distressing for the consumer, support people, representatives, other patients, staff and visitors. Wherever possible, alternative ways of managing a consumer’s behaviour should be used instead of seclusion and restraint.

“…Seclusion and restraint should only be used in accordance with approved protocols and best practice by properly trained professional staff in an appropriate environment…” (RANZCP 2021). More information about seclusion and restraint for Australian and New Zealand mental health legislation is on the RANZCP website (RANZCP 2017a, 2017b).

Seclusion and restraint are examples of restrictive practices in a care setting. A restrictive practice is any practice or intervention that restricts a person’s rights, including their freedom to move (Australian Government 2014; SQPSC 2016).

Minimising the use of seclusion and restraint in mental health services is a key focus across multiple sectors – including consumers, carers, governments and services. The National Mental Health Consumer and Carer Forum maintains that seclusion and restraint and other restrictive practices are avoidable and preventable (NMHCCF 2021). The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists acknowledges in its position statement that seclusion and restraint should only be used “…as a safety measure of last resort where all other interventions…” were considered (RANZCP 2021).

Another example of a restrictive practice is involuntary treatment. This is the compulsory assessment or treatment of people in mental health services without the person's consent being given. This can also be legally approved under certain conditions. More information about this is in the Involuntary treatment report.

Rates of seclusion and restraint are included in the Key Performance Indicators for Australian Public Mental Health Services. These indicators contribute to measuring the performance and progress of mental health services in Australia. The indicators are also reported on the Performance indicators monitoring page. Refer to the data source section for more information.

It is a policy priority in Australian mental health care to work towards eliminating seclusion (CHC 2017; National Mental Health Working Group 2005 as cited in NMHPSC 2013). This has been supported by changes to legislation, policy and clinical practice as well as:

- former national mental health committees, including the Safety Quality Partnership Standing Committee and Mental Health Information Strategy Standing Committee (Allan et al. 2017, SQPSC 2017)

- the Towards Eliminating Restrictive Practices (TERP) Forum, supported by all governments to share results, best practice and change to remove seclusion and restraint practices in mental health

- the National Mental Health Commission’s Statement on seclusion and restraint in mental health, which called for leadership including “…national monitoring and reporting on seclusion and restraint across jurisdictions and services” (NMHC 2015).

Where do I go for more information?

Many people improve clinically after care from public mental health services. Improvement is seen after about 72% of hospital care episodes according to clinician-rated measures (Gee et al. 2022). More information is in the Consumer outcomes report.

If the information presented raises any issues for you, these resources can help:

Rates are a way to calculate how often something happens in relation to something else. An example is the number of mental health-related prescriptions that are given for every 1,000 people.

In this report, rates are used to describe how often seclusion and restraint happen in Australian public hospital mental health services against a set number of days that a patient (or patients) used a bed in a service or group of services. This is known as patient days or bed days. This report uses statements to report the number of seclusion or restraint events for every 1,000 bed days.

Why do we use rates?

Using only the number of events shows how much an event has happened. Without context, this number does not help us to draw any further conclusions. However, if we measure the number of events in relation to something else, like a period of time, we can determine how often it occurs. This also allows us to compare different groups, as we can measure each group in the same way.

An example

Using rates means that a large mental health service can be assessed in the same way as a smaller service and we can better compare their performance. Here is an example with two hypothetical services.

| Service | Number of seclusion events | Number of bed days | Rate of seclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service A | 100 | 10,950 | 9 events per 1,000 bed days |

| Service B | 50 | 4,015 | 12 events per 1,000 bed days |

Service A reports more seclusion events than Service B (100 vs 50). Using these numbers alone, it appears that Service A uses seclusion more than Service B. However Service A is a larger service with more bed days, showing it has more service activity than Service B (10,950 vs 4,015). If we convert the number of seclusion events to a rate, we can see that Service A actually uses seclusion less often than Service B compared to the amount of activity the service provides (9 vs 12).

By assessing the activity of the two services against the same measurement (a rate), their activity can be compared despite the difference in size.

Direct comparisons between states and territories and over time should be made with caution for the following reasons.

- States and territories have different policies, regulations and legal criteria for the use of seclusion and restraint.

- States and territories have different systems in place for collecting data. Even though the data specifications provide some national compatibility there may be differences in counting and recording practices. These are noted in the General and Specific information tabs of the data download. It is expected that data quality will continue to improve over time, but these improvements also mean that year to year data methodologies may differ.

- High numbers of events for a few individuals can have a disproportional effect on the overall rates. For example, the increases in the state-wide Tasmanian seclusion rate between 2012–13 and 2013–14, for the ACT from 2017–18 to 2019–20, for SA in 2017–18 and 2018–19, and for WA in 2018–19, are due to a small number of clients having an above average number of seclusion events.

Data for smaller jurisdictions should be interpreted with caution as small changes in the number of seclusion or restraint events can have a marked impact on their overall rate. Further data quality information is in the data source section.

Target population represents the age group that the mental health service is intended to serve, not the age of individual patients.

Forensic services provide services largely for people whose health condition has led them to commit, or be suspected of committing, a criminal offence or make it likely that they will reoffend without adequate treatment or containment. The average duration of a seclusion event is reported excluding Forensic services, as forensic seclusion events are typically of longer duration, and substantially skew the overall duration average.

Seclusion and restraint data reported in this section are from the National Seclusion and Restraint Database (NSRD). Data are supplied by each Australian state and territory, under the Mental health Seclusion and Restraint National Best Endeavours Data Set (SECREST NBEDS) agreement. Historical data are available from 2008–09 for seclusion and 2015–16 for restraint. Data on the use of seclusion and restraint by hospital were reported for the first time in December 2018. Public reporting enables services to review their individual results against other states and territories, national rates and like services, thereby supporting service reform and quality improvement agendas.

Although seclusion and restraint may occur across a range of mental health service settings, the scope of the NSRD and SECREST NBEDS is hospital units that provide specialised mental health care. Only acute units are included, which provide short-term care. This service setting has been the focus of many associated quality improvement initiatives, including data collection and reporting developments.

Data Quality Statements are published annually on METEOR. Statements provide information on the institutional environment, timeliness, accessibility, interpretability, relevance, accuracy and coherence. Refer to the National Seclusion and Restraint Database; Mental health seclusion and restraint NBEDS 2015-, 2021; Quality Statement. Previous years' data quality statements are also accessible in METEOR.

Data from the National Seclusion and Restraint Database are also used for the Key Performance Indicators for Australian Public Mental Health Services (KPIs). These include the indicators KPI 15 Seclusion rate and KPI 16 Restraint rate draw on the National Seclusion and Restraint Database for reporting.

The original KPI set was released in 2005, with the aim to measure and improve the performance of public mental health services. The indicators have been revised over time through the former National Mental Health Performance Subcommittee (NMHPSC) of the former Mental Health Information Strategy Standing Committee (MHISSC), to drive and incorporate improvements made to data sources, jurisdictional implementation and results of nation-wide projects (NMHPSC 2013).

Rate of seclusion was added to the national KPI set in 2011 (NMHPSC 2013) and rate of restraint was added in 2018. Both indicators fall under the priority area of safety in mental health services, in which reducing the use of seclusion and restraint is considered a key aspect (CHC 2017; National Mental Health Working Group 2005 as cited in NMHPSC 2013).

In 2022 the new National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement and Bilateral Agreements were signed by the Australian Government and state and territory governments. While performance indicators for these agreements have not yet been established, seclusion and restraint are listed as priority data and Indicators for Development in the National Agreement (Australian Government 2022). Seclusion and restraint rates as measured in the KPIs will continue to be reported until indicators for the new National Agreement become available.

Key concepts

Key concept | Description |

|---|---|

Bed days (also known as patient days) means the occupancy of a hospital bed (or chair in the case of some same day patients) by an admitted patient for all or part of a day. The length of stay for an overnight patient is calculated by subtracting the date the patient was admitted from the date of separation and deducting days the patient was on leave. A same-day patient is allocated a length of stay of 1 day. Bed day statistics can be used to provide information on hospital activity that, unlike separation statistics, account for differences in length of stay. The bed day data presented in this report include days within hospital stays that occurred before 1 July provided that the separation from hospital occurred during the relevant reporting period (that is, the financial year period). This has little or no impact in private and public acute hospitals, where separations are relatively brief, throughput is relatively high and the bed days that occurred in the previous year are expected to be approximately balanced by the bed days not included in the counts because they are associated with patients yet to separate from the hospital and therefore yet to be reported. However, some public psychiatric hospitals provide very long stays for a small number of patients and, as a result, would have comparatively large numbers of bed days recorded that occurred before the relevant reporting period and may not be balanced by bed days associated with patients yet to separate from the hospital. | |

Hospital mental health care refers to specialised mental health services in a hospital or psychiatric hospital, which are staffed by health professionals with specialist mental health qualifications and/or training and have as their principal function the treatment and care of patients affected by mental illness. There are two types of hospital mental health care. Acute care hospital programs involve short‑term treatment for individuals with acute episodes of a mental disorder, characterised by recent onset of severe clinical symptoms that have the potential for prolonged dysfunction or risk to self and/or others. Other or non‑acute care refers to all other admitted patient programs, including rehabilitation and extended care services (METEOR identifier 288889). Seclusion and restraint data presented in this report are for Acute hospital mental health care only. | |

Restraint is defined as the restriction of an individual's freedom of movement by physical or mechanical means. Mechanical restraint The application of devices (including belts, harnesses, manacles, sheets and straps) on a person's body to restrict his or her movement. This is to prevent the person from harming themselves or endangering others or to ensure the provision of essential medical treatment. It does not include the use of furniture (including beds with cot sides and chairs with tables fitted on their arms) that restricts the person's capacity to get off the furniture except where the devices are used solely for the purpose of restraining a person's freedom of movement. The use of a medical or surgical appliance for the proper treatment of physical disorder or injury is not considered mechanical restraint. Physical restraint The application by health care staff of ‘hands-on’ immobilisation or the physical restriction of a person to prevent the person from harming themselves or endangering others or to ensure the provision of essential medical treatment. | |

| Seclusion is defined as the confinement of a person at any time of the day or night alone in a room or area from which free exit is prevented. Key elements include that:

The intended purpose of the confinement is not relevant in determining what is or is not seclusion. Seclusion applies even if the person agrees or requests the confinement. Seclusion also applies if the person agrees to or requests confinement of their own accord. However, if voluntary isolation or time alone is requested and the person is free to leave at any time then this is not considered seclusion. The awareness of the person that they are confined alone and denied exit is not relevant in determining what is or is not seclusion. The structure and dimensions of the area to which the consumer is confined is not relevant in determining what is or is not seclusion. The area may be an open area, for example, a courtyard. Seclusion does not include confinement of people to High Dependency sections of gazetted mental health units, unless it meets the definition. More information can be found in the data source section about jurisdictional consistency with this definition. |

Some specialised mental health services data are categorised using 5 target population groups (see METEOR identifier 682403):

Note that, in some states, specialised mental health beds for aged persons are jointly funded by the Australian and state and territory governments. However, not all states or territories report such jointly funded beds. |

Askew L, Fisher P and Beazley P (2019) ‘What are adult psychiatric inpatients’ experience of seclusion: a systematic review of qualitative studies’ Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 26:274–285, doi: 10.1111/jpm.12537

Brophy LM, Roper CE, Hamilton BE, Tellez JJ and McSherry BM (2016a) ‘Consumers’ and their supporters’ perspectives on barriers and strategies to reducing seclusion and restraint in mental health settings’ Australian Health Review, 40 (6): 599–604, doi: 10.1071/AH15128

Brophy LM, Roper CE, Hamilton BE, Tellez JJ and McSherry BM (2016b) ‘Consumers and their supporters’ perspectives on poor practice and the use of seclusion and restraint in mental health settings: results from Australian focus groups’ International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10 (6), doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0038-x

Foxlewin B (2012) What is happening at the Seclusion Review that makes a difference? – a consumer led research study, ACT Mental Health Consumer Network, accessed 19 August 2022.

Hansen A, Hazelton M, Rosina R and Inder K (2022) ‘What do we know about the experience of seclusion in a forensic setting? An integrative literature review’ International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31: 1109–1124, doi: 10.1111/inm.13002

Hawsawi T, Power T, Zugai J and Jackson D (2020) ‘Nurses’ and consumers’ shared experiences of seclusion and restraint: a qualitative literature review’ International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29 (5):831–845, doi: 10.1111/inm.12716

Muir-Cochrane E, O’Kane D and Oster C (2018) ‘Fear and blame in mental health nurses’ accounts of restrictive practices: implications for the elimination of seclusion and restraint’ International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27: 1511–1521, doi: 10.1111/inm.12451

NSW Health (2017) Review of seclusion, restraint and observation of consumers with a mental illness in NSW Health facilities, NSW Health, New South Wales Government, accessed 19 August 2022.

NMHCCF (National Mental Health Consumer and Carer Forum) (2021) Restrictive Practices in Australian Mental Health Services, NMHCCF, accessed 15 December 2022.

Allan J, Hanson G, Schroder N, O’Mahony A, Foster R & Sara G (2017) Six years of national mental health seclusion data: the Australian experience. Australasian Psychiatry, 25(3):277–281, doi:10.1177/1039856217700298.

Australian Government (2014) National Framework for Reducing and Eliminating the Use of Restrictive Practices in the Disability Service Sector (the ‘National Framework’), accessed 31 August 2021.

Australian Government (2022) The National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement, accessed 2 March 2023.

CHC (COAG [Council of Australian Governments] Health Council) (2017) The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, Department of Health, Canberra.

Gee A, Harris M, Burgess P, and Thomson J (2022) Use of a clinical outcomes national data collection in measuring performance of mental health services. 12th Health Services Research Conference, 30 Nov–2 Dec 2022, Sydney Australia.

Melbourne Social Equity Institute (2014) Seclusion and Restraint Project: Overview, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) (2015) Statement on seclusion and restraint in mental health, NMHC, Sydney, accessed December 2020.

NMHCCF (National Mental Health Consumer & Carer Forum) (2020) Restrictive Practices in Australian Mental Health Services, NMHCCF website, Canberra, accessed 7 February 2023.

NMHPSC (National Mental Health Performance Subcommittee) (2013) Key Performance Indicators for Australian Public Mental Health Services, 3rd edn, NMHPSC, Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council’s Mental Health Drug and Alcohol Principal Committee (MHDAPC).

RANZCP (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists) (2017a) Restraint – mental health legislation , RANZCP, Melbourne, accessed 15 February 2022.

RANZCP (2017b) Seclusion – mental health legislation, RANZCP, Melbourne, accessed 15 February 2022.

RANZCP (2021) Position Statement 61: Minimising and, where possible, eliminating the use of seclusion and restraint in people with mental illness, RANZCP, Melbourne, accessed 2 February 2022.

Sallway R, Gee A, and Thomson J (2022) The impact of making seclusion and restraint data visible: Innovation, collaboration and change in mental health care. 12th Health Services Research Conference, 30 Nov–2 Dec 2022, Sydney Australia.

SQPSC (Safety and Quality Partnership Standing Committee) (2016) National Principles for Communicating about Restrictive Practices with Consumers and Carers, NMHC, accessed 31 August 2021.

SQPSC (2017) Use of restraint in Australian specialised mental health hospital services: Discussion paper on the development of a national data collection.

Data coverage is 2008–09 to 2021–22 for seclusion, and 2015–16 to 2021–22 for restraint. This section was last updated in April 2023.