FDSV summary

On this page

- Introduction

- How common is family, domestic and sexual violence?

- What influences family, domestic and sexual violence?

- Who is at risk of family, domestic and sexual violence?

- What services or support do those who have experienced family, domestic and sexual violence use?

- What are the consequences of family, domestic and sexual violence?

- Where do I go for more information?

Family, domestic and sexual violence is a major health and welfare issue in Australia, occurring across all socioeconomic and demographic groups, but predominantly affecting women and children. These types of violence can have a serious impact on individuals, families and communities and can inflict physical injury, psychological trauma and emotional suffering. These effects can be long-lasting and can affect future generations.

For information, support and counselling contact 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit the 1800RESPECT website. See also Find support for a list of support services.

What is family, domestic and sexual violence?

Family violence is a term used for violence that occurs within family relationships, such as between parents and children, siblings, intimate partners or kinship relationships. Family relationships can include carers, foster carers and co-residents (for example in group homes or boarding residences).

Domestic violence is a type of family violence that occurs between current or former intimate partners (sometimes referred to as intimate partner violence).

Both family violence and domestic violence include a range of behaviour types such as:

- physical violence (for example, hitting, choking, or burning)

- sexual violence (for example, rape, penetration by objects, unwanted touching)

- emotional abuse, also known as psychological abuse (for example, intimidating, humiliating).

For more information, see Glossary.

Coercive control is often a significant part of a person’s experience of family and domestic violence. It is commonly used to describe a pattern of controlling behaviour, used by a perpetrator to establish and maintain control over another person.

Sexual violence can take many forms, including sexual assault, sexual threat, sexual harassment, child sexual abuse, and image-based abuse (NASASV 2021). However, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) uses a narrower definition of sexual violence, including only sexual assault and sexual threat, with sexual harassment and experiences of abuse in childhood reported separately (ABS 2023b).

Other forms of violence that can occur within the context of family and domestic violence include: stalking and elder abuse, with the latter occurring where there is an expectation of trust and/or where there is a power imbalance (Kaspiew et al. 2019).

How common is family, domestic and sexual violence?

The ABS PSS provides an estimate of the number of Australians who have been victims of family, domestic and sexual violence. While every experience of family, domestic or sexual violence is very personal and different, it is most common for this type of violence to be perpetrated against women, by men. There is currently no national data on the proportion of Australians who have perpetrated family, domestic and sexual violence.

The most recent PSS was conducted between March 2021 and May 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic (ABS 2023b). Because of some changes to the survey methodology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, some 2021–22 data are only available for women, including some time series.

According to the 2021–22 PSS:

-

1 in 6 women

1 in 18 men

in 2021–22 had experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a current or previous cohabiting partner since the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey -

1 in 4 women

1 in 7 men

in 2021–22 had experienced emotional abuse by a current or previous cohabiting partner since the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey -

1 in 6 women

1 in 13 men

in 2021–22 had experienced economic abuse by a current or previous cohabiting partner since the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey -

1 in 5 women

1 in 16 men

2021–22 had experienced sexual violence since the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

Physical and/or sexual family and domestic violence

Results from the 2021–22 PSS show that an estimated 3.8 million Australian adults (20% of the population) reported experiencing physical and/or sexual family and domestic violence since the age of 15. It is estimated that of all Australian adults:

- 11.3% (2.2 million) had experienced violence from a partner (current or previous cohabiting)

- 5.9% (1.1 million) had experienced violence from a boyfriend, girlfriend or date

- 7.0% (1.4 million) had experienced violence from another family member (ABS 2023c).

Experiences of partner violence in the 12 months before the survey (last 12 months) remained relatively stable for both men and women between 2005 and 2016. However, between 2016 and 2021–22 the proportion of women who experienced partner violence decreased from 1.7% in 2016 to 0.9% in 2021–22. There was also a decrease in the proportion of women who had experienced violence by any intimate partner (also includes current or previous boyfriend, girlfriend and date) between 2016 and 2021–22, from 2.3% in 2016 to 1.5% in 2021–22 (ABS 2023c).

For more information, see Family and domestic violence.

Partner emotional abuse and economic abuse

According to the 2021–22 PSS, an estimated 3.6 million Australian adults (19% of population) had experienced emotional abuse at least once by a partner since the age of 15. The proportion of women (23% or 2.3 million) who had experienced emotional abuse was higher than men (14% or 1.3 million). Estimates of partner emotional abuse in the 12 months before the survey have changed over time:

- the proportion of women who experienced partner emotional abuse was stable between 2012 and 2016, but decreased from 4.8% in 2016 to 3.9% in 2021–22

- the proportion of men who experienced partner emotional abuse increased from 2.8% in 2012 to 4.2% in 2016 before decreasing to 2.5% in 2021–22 (ABS 2023c).

It was also estimated that 2.4 million Australian adults (12% of the population) had experienced economic abuse by a partner since the age of 15, with the proportion of women (16%) who had experienced this type of abuse around double the proportion of men (7.8%) (ABS 2023c).

For more information, see Intimate partner violence.

Sexual violence

The 2021–22 PSS estimated 2.8 million Australians (14% of the population) experienced sexual violence (occurrence, attempt and/or threat of sexual assault) since the age of 15. It is estimated that of all Australian adults:

- 13% (2.5 million) had experienced sexual violence by a male

- 1.8% (353,000) had experienced sexual violence by a female (ABS 2023c).

Of all women:

- 11% (1.1 million) experienced at least one incident of sexual violence by a male intimate partner since the age of 15

- 2.1% (203,000) experienced at least one incident of sexual violence by a male family member since the age of 15

- 11% (1.1 million) experienced at least one incident of sexual violence by another known male since the age of 15

- 6.1% (605,000) experienced at least one incident of sexual violence by a male stranger since the age of 15 (ABS 2023c).

In the 12 months before the 2021–22 PSS, it is estimated that 1.9% of women experienced sexual violence. This does not represent a change from 2016 (ABS 2023c).

Based on the 2021–22 PSS, around 1 in 8 (13% or 1.3 million) women and 1 in 22 (4.5% or 427,000) men had experienced sexual harassment (see Glossary) in the last 12 months. This represents a decrease from 2016 for both women (previously 17%) and men (previously 9.3%) (ABS 2023c).

For more information, see Sexual violence.

Other forms of violence and abuse

Violence exists on a spectrum of behaviours. The same social and cultural attitudes underpinning family, domestic and sexual violence are at the root of other behaviours such as stalking. Technology can facilitate abuse and has become an important consideration in these types of violence.

Stalking is classified as unwanted behaviours (such as following or watching in person or electronically) that occur more than once and cause fear or distress and is considered a crime in every state and territory of Australia (ABS 2023b). Based on the 2021–22 PSS, 1 in 5 (20% or 2.0 million) women and around 1 in 15 (6.8% or 653,000) men had experienced stalking since the age of 15 (ABS 2023c).

Preliminary findings from the 2022 Australian eSafety Commissioner’s adult online safety survey of around 4,700 Australians aged 18–65 years, indicate that:

- 75% of those surveyed had a negative online experience in the 12 months prior to the survey, an increase from 58% in 2019

- 18% of those surveyed said their location had been tracked electronically without consent, an increase from 11% in 2019

- 16% of those surveyed said they received online threats of real-life harm or abuse, an increase from 9% (Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2023).

Due to the opt-in nature of the survey, these results may not be generalisable to the broader Australian adult population.

For more information, see Stalking and surveillance.

Family, domestic and sexual violence during the COVID-19 pandemic

The impacts of a pandemic can be wide-ranging with people experiencing different circumstances depending on their situation. Situational stressors, such as victims and perpetrators spending more time together, or increased financial or economic hardship, can be associated with increased severity or frequency of violence (Payne et al. 2020). It is also possible that increased protective factors, such as access to income support, time away from a perpetrator, or increased social cohesion, could suppress violence (Diemer 2023). Pandemics can also affect help-seeking and individual responses to violence, meaning support services have to adapt their delivery to new circumstances.

We continue to learn about the impact of the emergency phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on family, domestic and sexual violence, with some different patterns observed between research, drawing on a variety of data sources and methods, and national population prevalence data (Diemer 2023).

Results from the PSS showed that between 2016 and 2021–22 there was a decrease in the number of women experiencing physical and/or sexual partner violence in the 12 months before the survey, and a decrease in women and men experiencing partner emotional abuse. The rate of sexual violence for women remained stable. See How common is family, domestic and sexual violence?

The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) conducted an online survey of women’s experiences of violence during the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. While not comparable with the PSS, the survey of more than 10,000 women found that the pandemic coincided with first-time and escalating intimate partner violence for some women (Table 1). However, given this is a cross-sectional survey, a causal relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and women’s experiences of intimate partner violence cannot be established (Boxall and Morgan 2021).

| Physical violence | Sexual violence | Emotionally abusive, harassing and controlling behaviours | |

|---|---|---|---|

Overall prevalence of intimate partner violence (b) | 9.6% | 7.6% | 32% |

Experienced intimate partner violence for the first time (b) | 3.4% | 3.2% | 18% |

Reported that intimate partner violence had increased in frequency or severity (b, c) | 42% | 43% | 40% |

- Violence from a person the respondent had a relationship with during the previous 12 months. This includes current and former partners, cohabiting, or non-cohabiting.

- Of women aged 18 years and older who had been in a relationship longer than 12 months.

- Of women who had a history of violence from their current or most recent partner.

Source: Boxall and Morgan 2021.

For more information, see FDSV and COVID-19. See also ‘Chapter 2 - Changes in the health of Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic’ in Australia’s health 2022: data insights.

What influences family, domestic and sexual violence?

Social attitudes and norms shape the context in which violence occurs. The National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS) shows that in Australia, between 2009 and 2021, there was a positive shift in attitudes that reject gender inequality and violence against women. There was also an improvement in understanding of violence against women.

The NCAS indicated that in 2021 Australians, on average, had:

- higher understanding of violence against women compared to previous survey years (2009, 2013 and 2017)

- higher rejection of attitudes supportive of gender inequality compared to previous survey years

- improved attitudes towards sexual violence compared to 2017

- improved attitudes towards domestic violence compared to 2009 and 2013 (Coumarelos et al 2023).

While results were generally encouraging, some findings were concerning and highlight areas for improvement, select findings are summarised below.

Attitudes towards violence against women and gender inequality

Of all NCAS respondents in 2021:

- 25% believed that women who do not leave their abusive partners are partly responsible for violence continuing

- 34% agreed it was common for sexual assault accusations to be used as a way of getting back at men

- 23% believed domestic violence is a normal reaction to day-to-day stress

- 19% agreed that sometimes a woman can make a man so angry he hits her without meaning to

- 15% agreed that there is no harm in sexist jokes

- 41% agreed that many women misinterpret innocent remarks as sexist (Coumarelos et al. 2023).

For more information, see Community attitudes.

Understanding of violence against women

Of all NCAS respondents in 2021:

- 31% did not know that women are more likely to raped by a known person than a stranger

- 41% did not know where to access help for a domestic violence issue

- 43% did not recognise that men are the most common perpetrators of domestic violence

- 24% did not recognise that women are more likely than men to suffer physical harm from domestic violence (Coumarelos et al. 2023).

For more information, see Community understanding of FDSV.

Who is at risk of family, domestic and sexual violence?

Family, domestic and sexual violence occurs across all ages and demographics. However, some groups are at greater risk than others and/or may experience impacts and outcomes of violence that are more serious or long-lasting.

Children

Children are at greater risk of family, domestic and sexual violence.

According to the 2021–22 PSS, about 1 in 8 (13% or 2.6 million) people, aged 18 years and over, witnessed violence towards a parent by a partner before the age of 15. A higher proportion of people had witnessed partner violence against their mothers (12%, or 2.2 million) than their fathers (4.3%, or 837,000) (ABS 2023a).

The PSS also collects some information from adults about the nature and extent of violence experienced before and since the age of 15, for more information see Personal Safety, Australia.

The 2021 Australian Child Maltreatment Study surveyed people aged 16 years and over about experiences of maltreatment as a child. Of people surveyed, around:

- 3 in 10 (29%) had experienced sexual abuse by any person

- 3 in 10 (31%) had experienced emotional abuse by a parent or caregiver

- 1 in 11 (8.9%) had experienced neglect by a parent or caregiver

- 2 in 5 (40%) had experienced exposure to domestic violence (Haslam et al. 2023).

For more information, see Children and young people.

Child protection services

In Australia, state and territory governments are responsible for providing child protection services to anyone aged under 18 who has been, or is at risk of being, abused, neglected or otherwise harmed, or whose parents are unable to provide adequate care and protection. In 2021–22:

- Almost 178,000 Australian children (31 per 1,000) came into contact with the child protection system.

- Infants aged under one were most likely (38 per 1,000) to come into contact with the child protection system and adolescents aged 15–17 were the least likely (26 per 1,000).

- Emotional abuse, including exposure to family violence, was the most common primary type of abuse identified for children with substantiated cases (substantiations) (57% or 25,900 children). Neglect (21% or 9,400 children) was the next most common primary type of abuse substantiated, followed by physical abuse (13% or 6,100 children) and sexual abuse (9% or 4,000 children).

- Similar proportions of girls and boys were the subjects of substantiations for physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect. However, girls (12%) were more likely to be the subjects of substantiations for sexual abuse than boys (5%) (AIHW 2023a).

The rate of children who were the subject of notifications has increased from 44 per 1,000 in 2017–18 to 49 per 1,000 in 2021–22. However, the rate of children who were the subject of substantiations remained fairly stable in the 5 years to 30 June 2022.

Data on child protection services during the first 7 months after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic (March to September 2020) can be found in Child protection in the time of COVID-19.

For more information, see Child protection.

Women

More women than men experience family, domestic and sexual violence. Table 2 shows the proportion of people aged 18 and over who experienced violence from a partner since the age of 15.

| Women (%) | Men (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical and/or sexual violence from a partner | 16.9 | 5.5 |

| Physical violence from a partner | 14.9 | 5.3 |

| Sexual violence from a partner | 6.2 | n.p. |

| Emotional abuse from a partner | 22.9 | 13.8 |

| Economic abuse from a partner | 16.3 | 7.8 |

n.p. not published

Note: Where a person has experienced both physical and sexual violence by a cohabiting partner, they are counted separately for each type of violence they experienced but are counted only once in the aggregated total.

Source: ABS 2023c.

Women’s exposure to violence differs across the age groups. The 2021–22 PSS found that the prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence by a cohabiting partner (partner violence) among women declined with age. One in 39 (2.6%) women aged 18–34 experienced partner violence in the 2 years before the survey, compared with 2.2% for those aged 35–54 and 0.6% for those aged 55 and over (ABS 2023a).

The prevalence of sexual violence by any perpetrator among women also decreased with age. One in 8 (12%) women aged 18–24 experienced sexual violence in the 2 years before the survey, compared with 4.5% of those aged 25–34, 2.5% of those aged 35–44, 1.9%* for those aged 45–54 and 0.5%* of those aged 55 and over (ABS 2023e).

Note that estimates marked with an asterisk (*) should be used with caution as they have a relative standard error between 25% and 50%.

For more information, see Young women.

Other at-risk groups

Other social and cultural factors can also increase the risk of experiencing family, domestic and sexual violence. In some cases, these factors may overlap or combine to create an even greater risk. Additional factors that can increase the risk of violence include remoteness and socioeconomic area of residence, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity and cultural influences. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) women are particularly at risk and have much higher rates of hospitalisation because of family violence.

For more information, see Population groups.

What services or support do those who have experienced family, domestic and sexual violence use?

Responses to family, domestic and sexual violence are provided informally in the community and formally through justice systems, and treatment and support services.

-

2 in 5 women

2 in 5 men

in 2021–22 who had experienced previous partner violence since the age of 15 did not seek advice or support

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

The 2021–22 PSS found that there were differences in propensity to seek help, advice or support following partner violence depending on partner status and victim sex:

- 1 in 2 (45%, or 78,100) women who had experienced physical and/or sexual violence from a current partner did not seek advice or support about the violence.

- 2 in 5 women (37% or 574,000) and 2 in 5 men (39% or 166,000) who had experienced physical and/or sexual violence from a previous partner did not seek advice or support about the violence (ABS 2023a).

Data for men about seeking advice or support about current partner violence are not available (ABS 2023a).

The 2021–22 PSS collected detailed data from women about the most recent incident of sexual assault by a male that occurred in the last 10 years. Of the estimated 737,000 women who had experienced sexual assault by a male in the last 10 years:

- more than 2 in 5 (44% or 324,000) did not seek advice or support after the most recent incident

- 92% (680,000) said the police were not contacted (ABS 2023e).

For more information, see FDSV reported to police.

Police responses

When an incident of violence is reported to police by a victim, witness or other person, it can be recorded as a crime. The ABS collects data on selected family, domestic and sexual violence crimes recorded by police. In 2022:

- More than 1 in 2 (53% or 76,900) recorded assaults were related to family and domestic violence (excluding Victoria and Queensland), a 6.1% increase from 72,500 in 2021.

- One in 3 (33% or 71) recorded murders were related to family and domestic violence (ABS 2023d).

Since 2011, the number of sexual assault victims recorded by police has increased each year. It is unclear whether this change reflects an increased incidence of sexual assault, an increased propensity to report sexual assault to police, increased reporting of historical crimes, or a combination of these factors. Of all 2022 police-recorded sexual assaults, 69% were reported to police within one year (ABS 2023d).

For more information, see FDSV reported to police.

Homelessness services

People accessing specialist homelessness services (SHS) may need support due to family and domestic violence. Data cannot currently distinguish between victims and perpetrators of violence.

In 2022–23, SHS agencies assisted around 104,000 clients (38% of all SHS clients) who had experienced domestic and family violence. Of these clients:

- 3 in 4 (75% or 78,200) were female; and of the 20,500 clients aged 25–34, more than 9 in 10 (91% or 18,700) were female (AIHW 2023b)

- about 1 in 13 (7.7% or 8,100 clients) were living with disability (AIHW 2023c).

Of clients aged 10 and over who had experienced domestic and family violence:

- about 4 in 10 (42% or 34,200) also had a current mental health issue

- over 1 in 8 (12% or 9,400) had problematic drug and/or alcohol use (AIHW 2023b).

For more information, see Housing and Homelessness and homelessness services.

Hospitalisations

Hospitals provide health services for individuals who have experienced family, domestic and sexual violence. The family and domestic violence assault hospitalisations presented here are those where the perpetrator is coded as a family member (Spouse or domestic partner, Parent, or Other family member) in the hospital record. As information on cause of injury (such as assault) is not available in national emergency department data, family and domestic violence assault hospitalisations do not include presentations to emergency departments and underestimate overall hospital activity related to family and domestic violence. These hospitalisations also relate to more severe (and mostly physical) experiences of family and domestic violence.

-

In 2021–22, 3 in 10 (32% or 6,500) assault hospitalisations were due to family and domestic violence

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

Of all family and domestic assault hospitalisations in 2021–22:

- 73% (4,700) were for females and 27% (1,700) were for males

- 63% (4,100) had the perpetrator reported as a spouse or domestic partner

- 37% (2,400) had the perpetrator reported as a parent or other family member.

For more information, see Health services. See also Injury in Australia, Australia's Hospitals at a glance, and Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010–11 to 2018–19.

1800RESPECT

1800RESPECT is Australia’s national telephone and online counselling and support service for people affected by family, domestic and sexual violence, their family and friends and frontline workers. In 2020–21, 1800RESPECT responded to 286,546 telephone and online contacts. (These numbers include every contact to the service including disconnections, pranks and wrong numbers).

For more information, see Helplines and related support services.

What are the consequences of family, domestic and sexual violence?

Burden of disease

Burden of disease refers to the quantified impact of living with and dying prematurely from a disease or injury.

The Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 estimated the impact of various diseases, injuries and risk factors on total burden of disease for the Australian population. For females aged 15–44, intimate partner violence was ranked as the fourth leading risk factor for total disease burden, and child abuse and neglect was the leading risk factor. Child abuse and neglect was ranked third for males in the same age group (AIHW 2021a).

In 2018, intimate partner violence contributed to:

- 228 deaths (0.3% of all deaths among females) in Australia

- 1.4% of the total burden of disease and injury among Australian females.

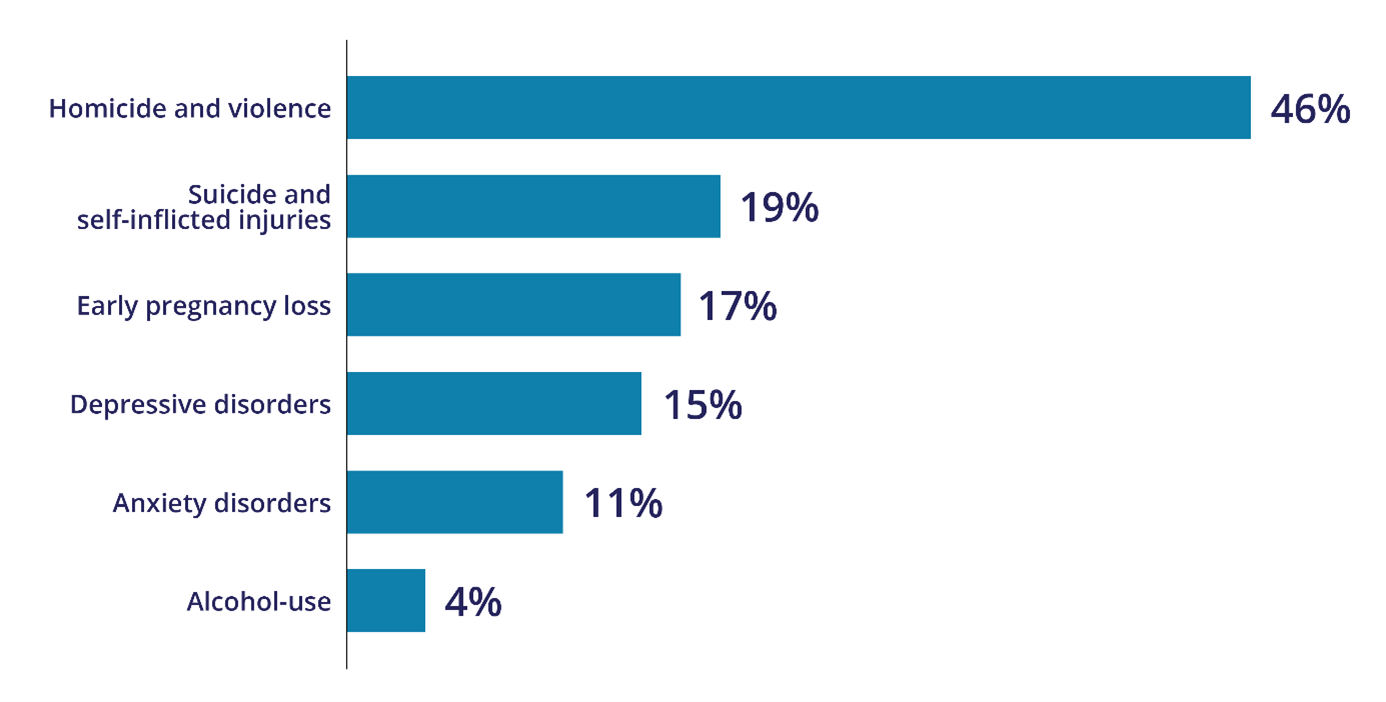

Figure 1 shows the estimated total burden attributable to intimate partner violence for females in 2018 by disease/health problem/injury. For example, it shows that almost half (46%) of all homicide and violence burden amongst females was attributable to intimate partner violence.

Figure 1: Total burden attributable to intimate partner violence, 2018

Note: Burden estimated in females only.

Source: AIHW 2021a.

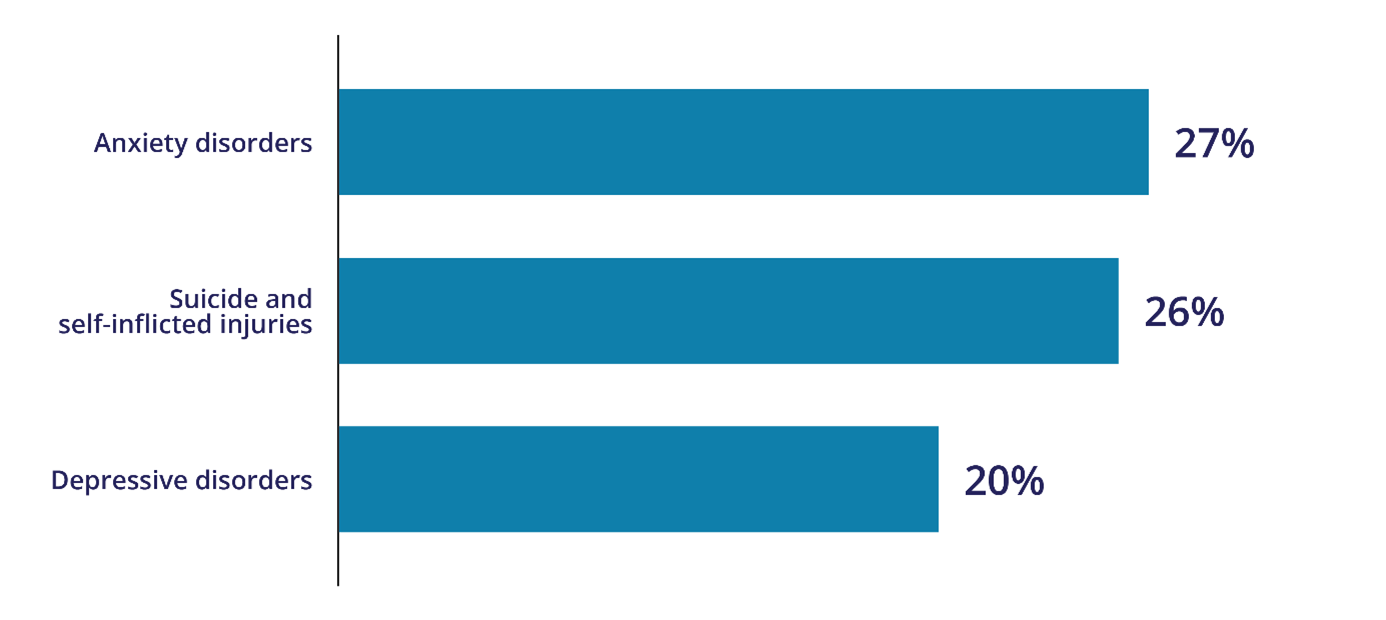

In 2018, child abuse and neglect contributed to:

- 813 deaths (0.5% of all deaths) in Australia

- 2.2% of the total burden of disease and injury.

Figure 2 shows the estimated total burden attributable to child abuse and neglect in 2018 by disease/health problem/injury.

Figure 2: Total burden attributable to child abuse and neglect, 2018

Source: AIHW 2021a.

For more information, see Health outcomes and Burden of disease.

Long-term health impacts

Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health demonstrated that women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse were more likely to have poor general health and to experience depression and bodily pain, compared with those who had not experienced sexual abuse during childhood (Coles et al. 2018). Women who had experienced childhood sexual or emotional or physical abuse had higher long-term primary, allied, and specialist health care costs in adulthood, compared with women who had not had these experiences during childhood (Loxton et al. 2018).

For more information, see Health outcomes.

Deaths

Between 1 July 2020 and 30 June 2021, the AIC’s National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) recorded 78 domestic homicide victims from 76 domestic homicide incidents (see Glossary). Data from the NHMP are from police and coronial records (Bricknell 2023).

Of all domestic homicide victims, 58% (45) were female. Of all female victims of domestic homicide, 56% (25) were killed by an intimate partner. For male victims of domestic homicide, 39% (13) were killed by an intimate partner (Bricknell 2023).

In 2020–21, the rate of domestic homicides was 0.3 per 100,000. The domestic homicide rate has halved since 1989–90, with an overall decrease of 56 per cent (Bricknell 2023).

A report, Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010–11 to 2018–19, found that people who had had a family and domestic violence hospitalisation were 10 times as likely to die due to assault, 3 times as likely to die due to accidental poisoning or liver disease, and 2 times as likely to die due to suicide, as a comparison group (AIHW 2021b).

For more information, see Domestic homicide and Deaths in Australia.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on health impacts of family, domestic and sexual violence, see:

- Family, domestic and sexual violence

- National Plan to End Violence against Women and their Children 2022–2032.

For information, support and counselling contact 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit the 1800RESPECT website.

ABS (2023a) Partner violence, 2021-22 financial year, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 2 February 2024.

ABS (2023b) Personal Safety, Australia methodology, 2021–22 financial year, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 17 April 2023.

ABS (2023c) Personal Safety, Australia, 2021–22 financial year, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 17 April 2023.

ABS (2023d) Recorded Crime - Victims, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 7 August 2023.

ABS (2023e) Sexual violence, 2021-22 financial year, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 30 October 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2021b) Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010–11 to 2018–19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2022.

AIHW (2023a) Child protection Australia 2021–22, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 June 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2022–23, AIHW website, accessed 13 February 2024.

AIHW (2023c) Specialist Homelessness services collection, customised request, AIHW.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021) Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of women in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2022.

Bricknell S (2023) Homicide in Australia 2020–21, Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Government, accessed 19 April 2023.

Coles J, Lee A, Taft A, Mazza D and Loxton D (2018) ‘Childhood sexual abuse and its association with adult physical and mental health: results from a national cohort of young Australian women’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(11):1929–1944, doi.org/10.1177/0886260514555270.

Coumarelos C, Weeks N, Bernstein S, Roberts N, Honey N, Minter K and Carlisle E (2023) Attitudes matter: The 2021 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), Findings for Australia, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, accessed 23 April 2023.

Diemer K (2023) The unexpected drop in intimate partner violence, Pursuit, The University of Melbourne, accessed 31 October 2023.

Haslam D, Mathews B, Pacella R, Scott JG, Finkelhor D, Higgins DJ, Meinck F, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Lawrence D and Malacova E (2023) The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study: Brief Report, Queensland University of Technology, accessed 2 May 2023.

Kaspiew R, Carson R, Dow B, Qu L, Hand K, Roopani D, Gahan L and O'Keeffe D (2019) Elder Abuse National Research – Strengthening the Evidence Base: research definition background paper, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2022.

Loxton D, Townsend N, Dolja-Gore X, Forder P and Coles J (2018) ‘Adverse childhood experiences and health-care costs in adult life’, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 4:1–15, doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1523814.

Payne J, Morgan A and Piquero A (2020) ‘COVID-19 and social distancing measures in Queensland Australia are associated with short-term decreases in recorded violent crime’, Journal of Experimental Criminology, 18: 89–113, doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09441-y.

NASASV (National Association of Services Against Sexual Violence) (2021) Standards of practice manual for services against sexual violence 3rd edition, NASASV, accessed 20 April 2022.

Office of the eSafety Commissioner (2023) Adults’ negative online experiences 2022, Office of the eSafety Commissioner, Australian Government, accessed 17 April 2023.

This page was last updated 12 April . All information on this page is the most recent available, as at that date.

- Previous page Community attitudes towards sexual violence

- Next page Data downloads