Secondary school education

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) Secondary school education, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 October 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Secondary school education. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/secondary-education

MLA

Secondary school education. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 25 June 2021, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/secondary-education

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Secondary school education [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021 [cited 2024 Oct. 22]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/secondary-education

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2021, Secondary school education, viewed 22 October 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/secondary-education

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

On this page:

- Key findings

- How many young people attend school?

- Has school attendance changed over time?

- Are attendance levels the same for everyone?

- How have Year 9 students performed on reading and numeracy tests?

- Have reading and numeracy outcomes changed over time?

- Are reading and numeracy outcomes the same for everyone?

- How does Australia compare internationally?

- Sense of belonging at school

- Where do I find more information?

- References

- Technical notes

Key findings

- In 2019, 65% of Year 9 students attended school on at least 90% of the total possible school days.

- Between 2008 and 2019, the proportion of Year 9 students who achieved at or above the national minimum standard for numeracy increased over time (94% to 96%) and for reading remained stable (varying between 91% and 93%).

- In 2018, Australian high school students’ sense of belonging at school was below the OECD average.

Secondary school education is a crucial part of young people’s lives. Their experiences and achievements at school have lasting effects on their health and wellbeing as well as their future productivity and contribution to society.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) sees a student’s reading and numeracy as fundamental to their educational achievement. These abilities, in turn, not only help students to engage with society but also affect their future employment prospects (OECD 2016).

School attendance contributes importantly to a student’s academic achievement and affects further education and future employment opportunities (SCRGSP 2020). It is also a measure of a student’s behavioural engagement with school.

A student’s attendance pattern is set down in the first years of school. Non‑attendance leads to poorer academic achievement, with the effects of absences accumulating over time (Hancock et al. 2013). Non-attendance is also associated with negative social outcomes, such as social isolation and emotional and behavioural difficulties (AITSL 2019).

A student’s sense of belonging relates to how connected, respected and supported students feel at school. A greater sense of belonging is associated with higher academic motivation, achievement and self-esteem (OECD 2019a). Sense of belonging is also a measure of a student’s emotional engagement with school (SCRGSP 2020).

Sense of belonging is, however, only one aspect of student wellbeing. The Australian Student Wellbeing Framework is a national framework for student wellbeing that addresses many aspects of wellbeing and outlines an overarching vision, principles and practices to improve and maintain safety, wellbeing and positive relationships within the school community (Education Services Australia 2020).

For data on young people who attained Year 12 (or equivalent) or Certificate III (or above) see Non-school qualifications.

Box 1: Data sources and national performance measures

Data reported in this section focus on national measures relating to secondary school students.

On 1 January 2019, the National School Reform Agreement (NSRA) replaced the National Education Agreement (NEA) and the National Education Reform Agreement (NERA).The NSRA is a joint agreement between the Australian, state and territory governments to lift student outcomes across Australian schools (COAG 2019). It sets out 8 reforms to be implemented nationally over the next 5 years, along with national targets and measures. For more information, see The National School Reform Agreement.

Measures on school attendance and literacy and numeracy from the NSRA are presented in this section. To provide a longer time series on these topics, data for measures under the former NEA and NERA agreements are also included.

School attendance data

School attendance data are sourced from the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) National Student Attendance Data Collection. ACARA, on behalf of the Education Council, developed the National Standards for Student Attendance Data Reporting (national standards) to standardise reporting across Australia for comparability purposes.

Student attendance rates were also a measure under the NEA and the NERA. As national time-series data are available for years 2014 to 2019, attendance rate data are also included in this section. Student attendance rates refer to the number of days of school attended as a percentage of the total number of possible school days.

Student attendance levels refer to the proportion of students whose attendance rate in Semester 1 is equal to or greater than 90% (referred to in this section as ‘at least 90%’). Student attendance levels are a measure under the NSRA. National data on student attendance levels have been collected only from 2018.

National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN)

NAPLAN tests have been conducted annually for all students across Australia in years 3, 5, 7 and 9 since 2008. They yield nationally comparable data. NAPLAN data includes those on reading, writing, spelling, language conventions (grammar and punctuation) and numeracy. This section focuses on Year 9 reading and numeracy only.

Reading and numeracy data in this section are expressed in terms of:

- the mean score of students (a previous measure in the NEA and the NERA)

- the percentage of students who achieved at or above the national minimum standard (also a previous measure in the NEA and the NERA)

- the proportion of students in the top and bottom levels of performance (that is, the top 2 and bottom 2 bands for Year 9 students (a measure in the NSRA)).

NAPLAN mean scores generally range from 0–1,000 points, with higher scores indicating better performance; the scores are equated so that a score of 700 in reading has the same meaning in 2008 as in 2019 (ACARA 2019a).

NAPLAN and COVID-19

NAPLAN tests were cancelled for 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic but are expected to restart in 2021 (ACARA 2020).

Programme for International Student Assessment

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a triennial survey of 15-year-old students around the world (see Technical notes). It focuses on the core school subjects of science, reading and mathematics. Additional questionnaires are provided to students to gather contextual information, such as socioeconomic background, and attitudes towards school (for example, a sense of belonging). This section focuses on the core school subjects of reading and mathematics.

How many young people attend school?

Attendance level is a measure of the proportion of students that attended school on at least 90% of the total possible school days. In 2019, the attendance level of Year 9 students was 65%.

The attendance levels were:

- similar among males (65%) and females (66%)

- higher for non-government schools (73%) than government schools (60%) (ACARA 2019b).

Has school attendance changed over time?

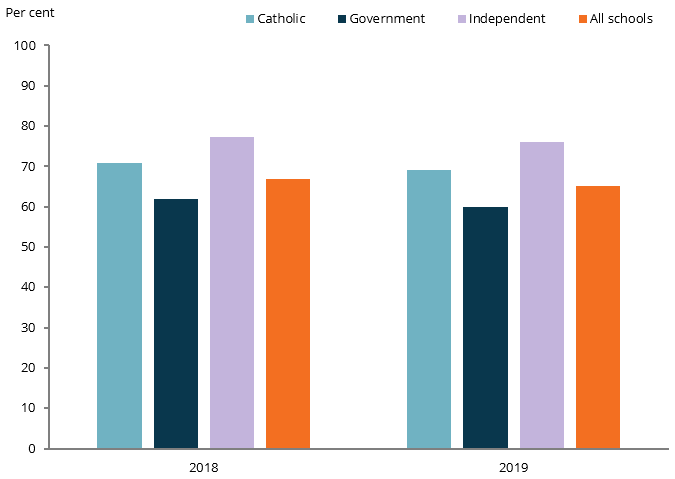

Between 2018 and 2019:

- the attendance level for Year 9 students decreased slightly

- independent schools had the highest attendance levels, followed by Catholic schools and then government schools

- the difference in attendance level between independent schools and government schools was the greatest in 2019 (16 percentage points) (Figure 1).

As student attendance rate has been recorded for longer than attendance level and it was a measure under the former NEA and NERA agreements.

Between 2014 and 2019:

- the student attendance rate for Year 9 students remained steady (between 89–91%)

- independent schools had a consistent pattern of having the highest attendance rates, followed by Catholic schools and then government schools

- the difference in attendance rate between independent schools and government schools was the greatest in 2019 (5 percentage points) (ACARA 2019b).

Figure 1: Year 9 student attendance levels, by school sector, 2018–2019

Chart: AIHW.

Source: ACARA 2019b.

Are attendance levels the same for everyone?

In 2019, based on data from the ACARA National Student Attendance Data Collection, Year 9 student attendance levels were higher in Major cities (68%) than in Inner regional (60%), Outer regional (58%), Remote (46%) and Very remote (22%) areas (ACARA 2019b).

Attendance data for students from a low socio-educational advantage background or for students with disability are not currently available in this Collection.

How have Year 9 students performed on reading and numeracy tests?

In 2019, based on NAPLAN data, among students in Year 9, the:

- reading mean score was 581.3 (574.1 for males and 588.8 for females)

- proportion that achieved at or above the minimum standards for reading was 92% (94% for females and 89% for males)

- proportion in the top 2 bands for reading was 21% (with 22% in the bottom 2 bands)

- numeracy mean score was 592.1 (597.0 for males and 587.0 for females)

- proportion who achieved at or above the minimum standards for numeracy was 96% (97% for females and 96% for males)

- proportion in the top 2 bands for numeracy was 24% (with 18% in the bottom 2 bands) (ACARA 2019c; Productivity Commission 2020).

Have reading and numeracy outcomes changed over time?

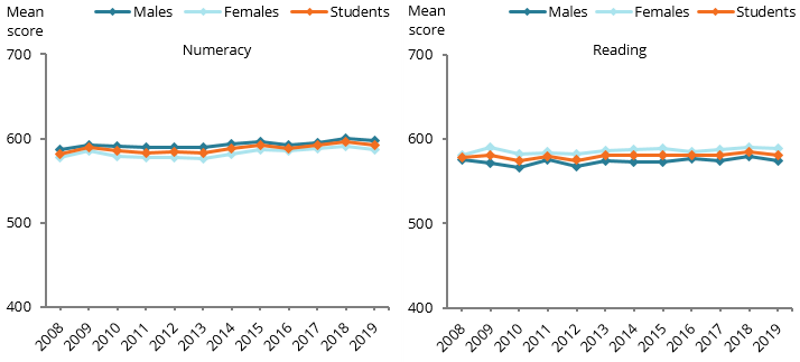

Between 2008 and 2019, among Year 9 students, the:

- reading mean score remained relatively stable over time (578.0 in 2008 and 581.3 in 2019) (Figure 2)

- proportion who achieved at or above the national minimum standard for reading also remained stable at 91–93% (ranging between 89% and 92% for males, and between 93% and 95% for females) (ACARA 2019c)

- numeracy score remained relatively stable over time (582.2 in 2008 and 592.1 in 2019) (Figure 2)

- proportion who achieved at or above the national minimum standard for numeracy increased (94% to 96%) (this was true for both males (94% to 96%) and females (94% to 97%)) (ACARA 2019c).

Figure 2: National mean scores for Year 9 students, by sex, 2008 to 2019

Chart: AIHW.

Source: ACARA 2019c.

Are reading and numeracy outcomes the same for everyone?

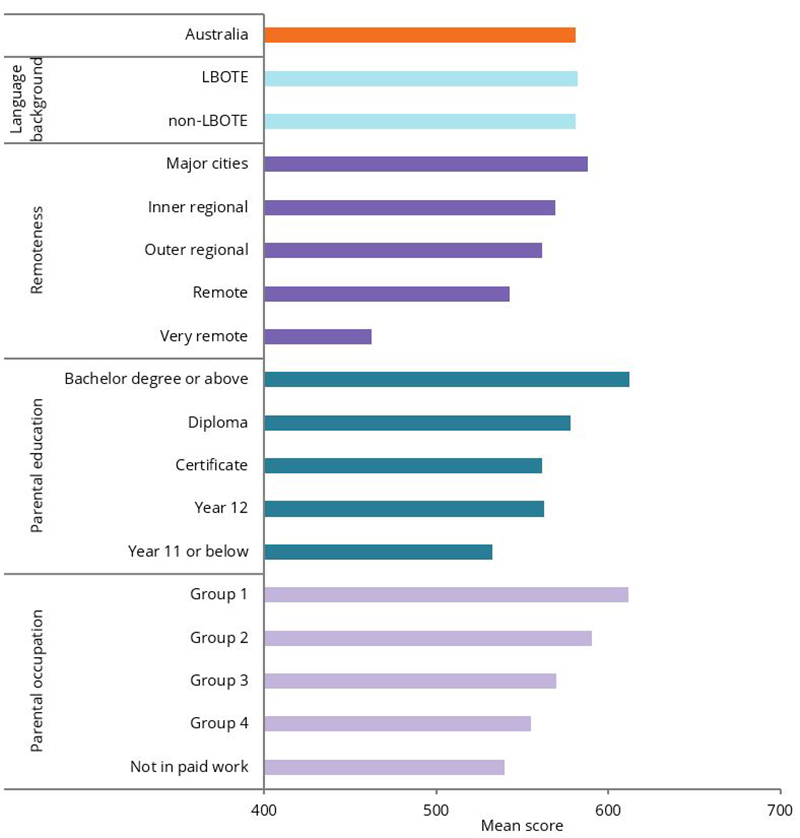

In 2019, based on NAPLAN data, the mean reading score for Year 9 students varied between population groups. The mean reading score was:

- similar for students from a language background other than English (LBOTE) and their non-LBOTE counterparts

- higher for students in Major cities than in Inner regional, Outer regional, Remote and Very remote areas

- higher for students whose parents hold a bachelor degree or higher than for students whose parents hold a diploma, certificate, Year 12 or equivalent, Year 11 or equivalent, or below

- higher for students with parents in Occupation Group 1, which includes senior managers and qualified professionals, than for parents in occupation groups 2, 3 or 4 or for parents not in paid work (Figure 3).

Figure 3: National mean scores for reading for Year 9 students, by selected population groups, 2019

Note: Group 1: Senior management and qualified professionals; Group 2: Other business managers and associated professionals; Group 3: Tradespeople, clerks, skilled office people, sales and service staff; Group 4: Machine operators, hospitality staff, assistants, labourers; Not in paid work: Not in paid work in the previous 12 months.

Chart: AIHW.

Source: ACARA 2019c.

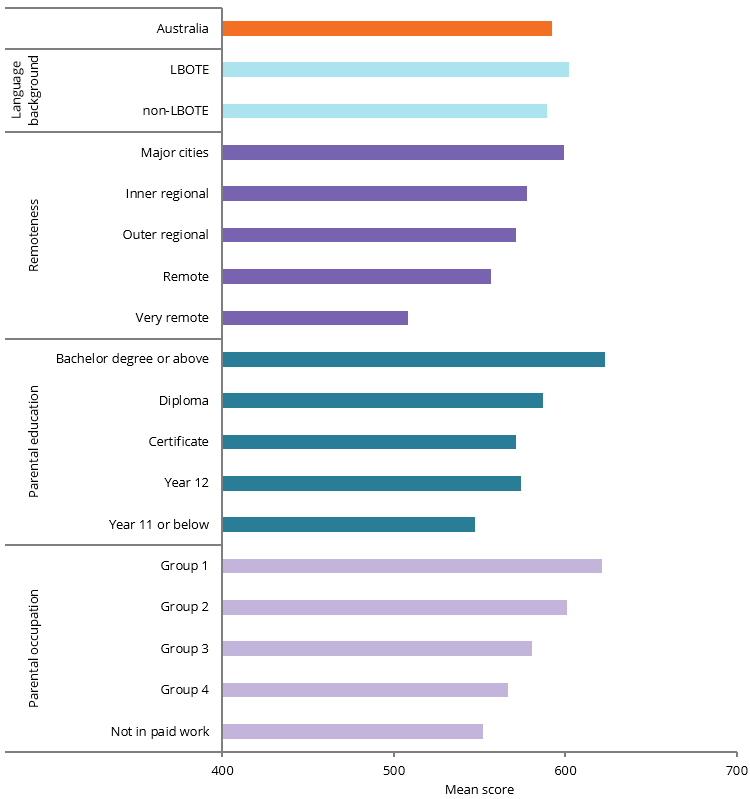

The mean numeracy score for Year 9 students also varied between population groups. The numeracy score was:

- higher for students from a language background other than English (LBOTE) than for their non-LBOTE counterparts

- higher for students in Major cities than in Inner regional, Outer regional, Remote and Very remote areas

- higher for students whose parents hold a bachelor degree or higher compared with students whose parents hold a diploma, certificate, Year 12 or equivalent, Year 11 or equivalent, or below

- higher for students with parents in Occupation Group 1, which includes senior managers and qualified professionals, than for parents in occupation groups 2, 3 and 4, and parents not in paid work (Figure 4).

Figure 4: National mean scores for numeracy for Year 9 students, by selected population groups, 2019

Note: Group 1: Senior management and qualified professionals; Group 2: Other business managers and associated professionals; Group 3: Tradespeople, clerks, skilled office people, sales and service staff; Group 4: Machine operators, hospitality staff, assistants, labourers; Not in paid work: Not in paid work in the previous 12 months.

Chart: AIHW.

Source: ACARA 2019c.

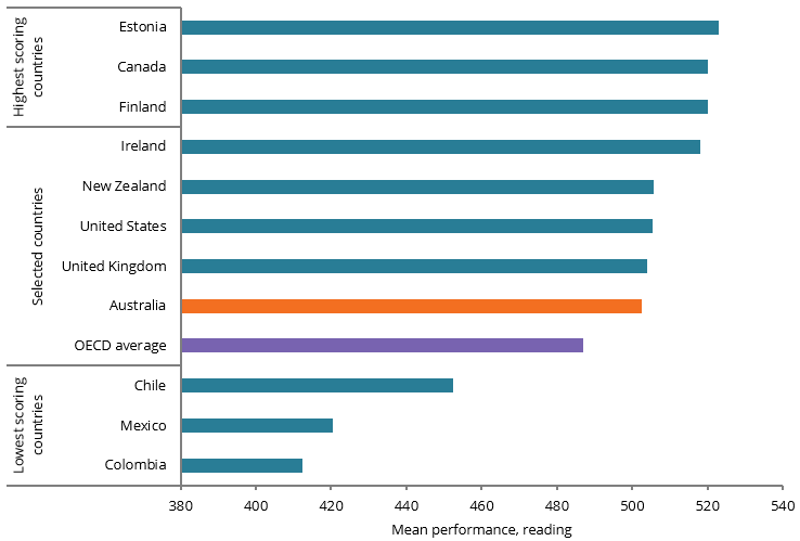

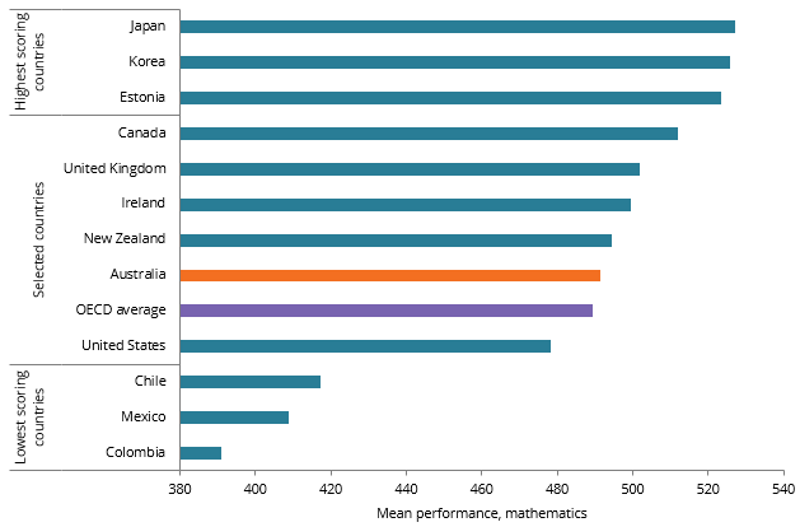

How does Australia compare internationally?

Based on data from PISA 2018, the mean performance of Australian students (aged 15, see Technical notes) was higher than the OECD average in reading (503 compared with 487) but similar to the OECD average in mathematics (OECD 2019b) (figures 5 and 6).

Of the 37 OECD countries that took part in PISA 2018, Australia outperformed 21 of them in reading and 11 in mathematics (OECD 2019b).

Of a select group of OECD countries, Australia performed similarly to:

- New Zealand, the United States and the United Kingdom in reading (Figure 5)

- New Zealand in mathematics (OECD 2019b) (Figure 6).

Since the first measurement of PISA (2000), the performance of Australian students has been declining across reading and mathematics (see Australia’s welfare 2019).

Figure 5: Reading mean performance, by selected OECD countries, 2018

Notes

- Only OECD countries are shown, with only main English-speaking countries selected for comparison. For a comparison of all OECD countries and PISA partner countries and economies, see OECD 2019b.

- PISA 2018 results for reading performance are reported as missing for Spain; see OECD 2019b.

Chart: AIHW.

Source: OECD 2019b.

Figure 6: Mathematics mean performance by selected OECD countries, 2018

Notes

- Only OECD countries are shown, with only main English-speaking countries selected for comparison. For a comparison of all OECD countries and PISA partner countries and economies, see OECD 2019b.

- PISA 2018 results for reading performance are reported as missing for Spain; see OECD 2019b.

Chart: AIHW.

Source: OECD 2019b.

Sense of belonging at school

Sense of belonging has been associated with social and academic outcomes, including higher academic motivation, self-esteem and achievement (OECD 2019a).

The PISA survey calculates a Sense of Belonging index, based on the responses to 6 statements used to measure sense of belonging and compare OECD countries. These 6 responses show that most students in Australia feel socially connected at school (tables 1 and 2).

Statements related to sense of belonging | Australia | OECD average |

|---|---|---|

I make friends easily at school | 76 | 75 |

I feel like I belong at school | 68 | 71 |

Other students seem to like me | 85 | 81 |

Note: The OECD average refers to the average across 36 OECD countries in PISA 2018 (not including Israel).

Source: OECD 2019a.

Statements related to sense of belonging | Australia | OECD average |

|---|---|---|

I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school | 73 | 80 |

I feel awkward and out of place in my school | 75 | 80 |

I feel lonely at school | 81 | 84 |

Note: The OECD average refers to the average across 36 OECD countries in PISA 2018 (not including Israel).

Source: OECD 2019a.

The index of sense of belonging has an average of 0 and standard deviation of 1 across OECD countries and is calculated using the responses to the 6 statements in tables 1 and 2. The sense of belonging index score for Australia is –0.19, lower than the OECD average (0) (SCRGSP 2020).

Australian students from metropolitan areas reported a greater sense of belonging (–0.16) than students from provincial (–0.28) and remote (–0.26) areas (SCRGSP 2020) (For more information, see Technical notes).

Australian students from the highest socioeconomic quartile reported a greater sense of belonging (–0.06) than students in the other 3 quartiles (–0.16, –0.22 and –0.32 in the third, second and lowest quartile, respectively) (SCRGSP 2020) (For more information, see Technical notes).

Where do I find more information?

For information on topics related to wellbeing in this report, see:

For information on Indigenous young people and literacy and numeracy, see:

- Section 2.04 of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (HPF) report 2020 or Section 3.1, Education of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth health and wellbeing 2018.

For information on literacy and numeracy levels among children aged 0–14, see:

- literacy and numeracy in Australia’s Children.

For more information on:

- state and territory school student engagement surveys, see:

- New South Wales: Tell Them From Me

- Victoria: About You – Student Health and Wellbeing Survey, Student Attitudes to School Survey.

- South Australia: The Wellbeing and Engagement Collection

- Tasmania: Student Wellbeing Survey

- Australian Capital Territory: The Australian School Climate and School Identification Measurement Tool

- state and territory frameworks and initiatives for student wellbeing, see:

- New South Wales: Wellbeing Framework for Schools

- Victoria: The Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System Outcomes Framework

- Queensland: Student Learning and Wellbeing Framework

- Western Australia: The Wellbeing Monitoring Framework

- South Australia: Wellbeing for Learning and Life framework

- Tasmania: Tasmanian Child and Youth Wellbeing Framework and the 2018–2021 Child and Student Wellbeing Strategy: Safe, Well and Positive Learners

- Australian Capital Territory: Engaging Schools Framework

- Northern Territory: Framework for Inclusion 2019–2029.

ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) 2019a. NAPLAN Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2019. Sydney: ACARA. Viewed 20 April 2021.

ACARA 2019b. Student attendance. Sydney: ACARA. Viewed 20 April 2021.

ACARA 2019c. NAPLAN 2019 summary results. Sydney: ACARA. Viewed 18 May 2020.

ACARA 2020. NAPLAN FAQs: NAPLAN—COVID-19. Sydney: ACARA. Viewed 26 November 2020.

AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership) 2019. Spotlight—attendance matters. Melbourne: AITSL. Viewed 19 August 2020.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) 2019. The National School Reform Agreement. Canberra: Department of Education and Training. Viewed 19 August 2020.

Education Services Australia 2020. Australian Student Wellbeing Framework. Student Wellbeing Hub. Melbourne: Education Services Australia. Viewed 1 September 2020.

Hancock KJ, Shepherd CCJ, Lawrence D & Zubrick SR 2013. Student Attendance and Educational Outcomes: every day counts. Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Perth: Telethon Kids Institute. Viewed 20 April 2021.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) 2016. Building skills for all in Australia: policy insights from the survey of adult skills. OECD Skills Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing. Viewed 14 August 2020.

OECD 2019a. PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): what school life means for students’ lives. Paris: OECD Publishing. Viewed 14 August 2020.

OECD 2019b. PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): what students know and can do. Paris: OECD Publishing. Viewed 14 August 2020.

Productivity Commission 2020. Performance reporting dashboard. Education: National School Reform Agreement details. Canberra: Productivity Commission. Viewed 13 August 2020.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2020. Report on Government Services 2020. Canberra: Productivity Commission. Viewed 15 December 2020.

Thomson S, De Bortoli L, Underwood C & Schmid M 2019. PISA 2018: Reporting Australia’s Results. Volume I Student Performance. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. Viewed 20 April 2021.

PISA

- The PISA survey covers students who are aged between 15 years 3 months and 16 years 2 months at the time of assessment and who are enrolled in school and have completed at least 6 years of formal schooling, regardless of the type of institution in which they are enrolled, and whether they are in full-time or part‑time education, whether they attend academic or vocational programmes, and whether they attend public or private schools or foreign schools within the country (PISA 2019a).

- The geographic categories metropolitan, provincial and remote areas are based on the agreed Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs (now Education Council) Geographic Location Classification presented in the Report on Government Services 2020.

- Socioeconomic background quartiles are based on the measure of socioeconomic background developed by PISA: the economic, social and cultural status index. This index incorporates information such as the highest level of occupation and education of a student’s parents. Using this index participating students are distributed into quartiles of socioeconomic background (Thomson et al. 2019).

For general technical notes relating to this report, see also Methods.

Australia's youth: