Expenditure on mental health-related services

On this page:

- Key points

- Spotlight data

- How much was spent on specialised mental health services?

- Public sector specialised mental health hospital services

- Australian Government expenditure on mental health-related services

- Australian Government expenditure on Medicare mental health services (MBS)

- Australian Government expenditure on mental health-related subsidised prescriptions (PBS)

- Where can I find more information?

Key points

Spending on mental health-related services

increased from $10.9 billion in 2017–18 to $12.2 billion in 2021–22.

Almost $1.5 billion

was spent on mental health-related Medicare services and $672 million on mental health-related prescriptions in 2022–23.

$7.4 billion

was spent on state and territory mental health services in 2021–22.

Please note throughout this section all health expenditure (unless otherwise specified) utilises constant prices, also referred to as ‘in real terms’. Constant price estimates are derived by adjusting the current price to remove the effects of inflation and allow for spending in different years to be compared and for changes in spending to reflect changes in the volume of health goods and services.

Please note that Australian Capital Territory non-Commonwealth data for 2021–22 was not available at the time of publication. Updated data for ACT will be published when available. National total calculations for State and Territory jurisdictional (non-Commonwealth data) for 2021–22 do not include ACT data. Caution should be exercised when conducting time series analyses.

Summary

This section reviews the available information on recurrent expenditure (running costs), health expenditure (what was spent), and health funding (funding provided and who provided the funds) for mental health-related services in Australia. These are distinct but related concepts essential to understanding the financial management of the health system.

This section also summarises data for national expenditure by either the Australian Government or aggregate totals of Australian Government and state and territory governments. During 2021–22, national recurrent spending on mental health-related services was estimated to be almost $12.2 billion, an annual average increase of 3% since 2017–18 in real terms (i.e., adjusted for inflation). Overall, national spending increased from $439 per capita in 2017–18 to $472 per capita during 2021–22, an average annual increase of 2% in real terms.

In 2021–22, state and territory governments spent 60% ($7.3 billion), the Australian Government 35% ($4.3 billion), and private health insurance funds and other third-party insurers 5% ($0.6 billion) of recurrent expenditure.

In real terms, between 2017–18 and 2021–22, Australian Government spending increased by an average annual rate of 4%, and state and territory government spending increased by an average annual rate of 3%.

In current prices, about $1.5 billion was spent on mental health-related Medicare services and $672 million on mental health-related prescriptions in 2022–23.

Data on expenditure and funding, calculated in both current and constant prices, are derived from a variety of sources, as outlined in the data source section.

Spotlight data

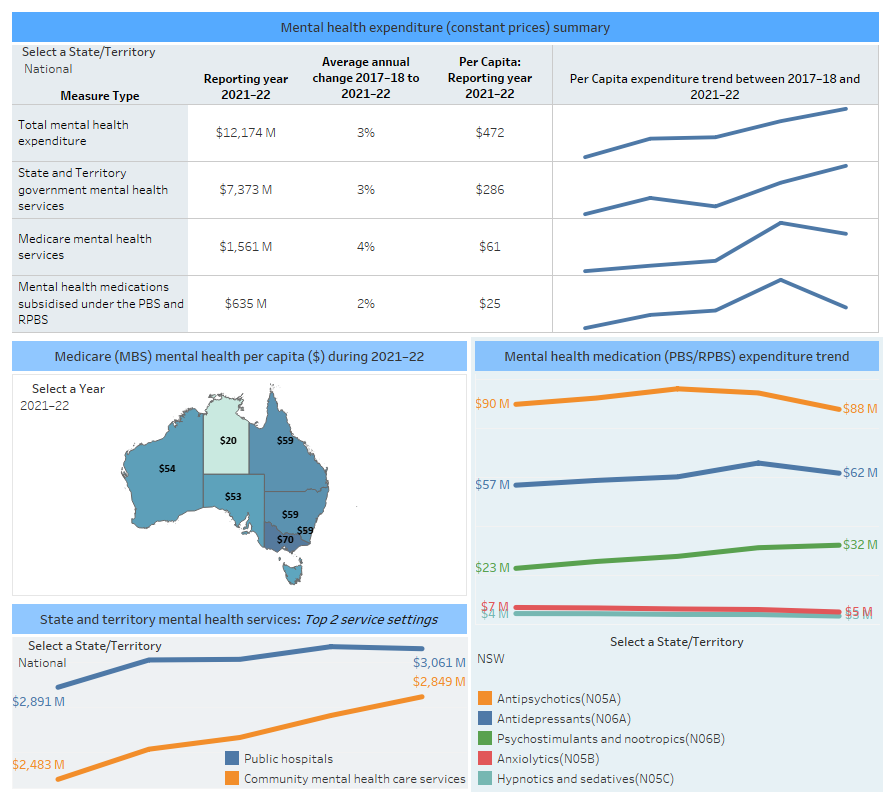

Overview of mental health expenditure, 2017–18 to most recent year of data

Spotlight figure displaying an overview of mental health expenditure on mental health services nationally and for states and territories between 2017–18 and the most recent year of data. A series of line graphs summarise various expenditure in constant price. Another figure summarises state and territory Medicare mental health expenditure per capita ($) which can be displayed as single year between 2017–18 to 2022–23. Another line graph summarises the observed time series trends for expenditure ($) on the top two service settings (Public hospitals and Community mental health care services) from 2017–18 to 2021–22 which can be filtered by state and territory or the national level. The last line graph shows observed time series trends for expenditure ($) on the top 5 mental health medication types via PBS/RPBS 2017–18 to 2022–23 which can be filtered by state and territory or the national level.

Note:

The most recent year for total Mental health expenditure and State and Territory government mental health expenditure statistics is 2021–22, and the most recent year for MBS and PBS subsidy statistics is 2022–23.

Data not published will appear as '0'. Refer to data tables for further details.

Non-commonwealth ACT data for 2021–22 was not available at the time of publication. Updated data for ACT will be published when available. National total calculations for State and Territory jurisdictional (non-Commonwealth) expenditure for 2021–22 do not include ACT data. Caution should be exercised when conducting time series analyses.

Source: Expenditure on mental health services tables EXP.2, EXP.19, EXP.29, EXP.33 and EXP.34

How much was spent on specialised mental health services?

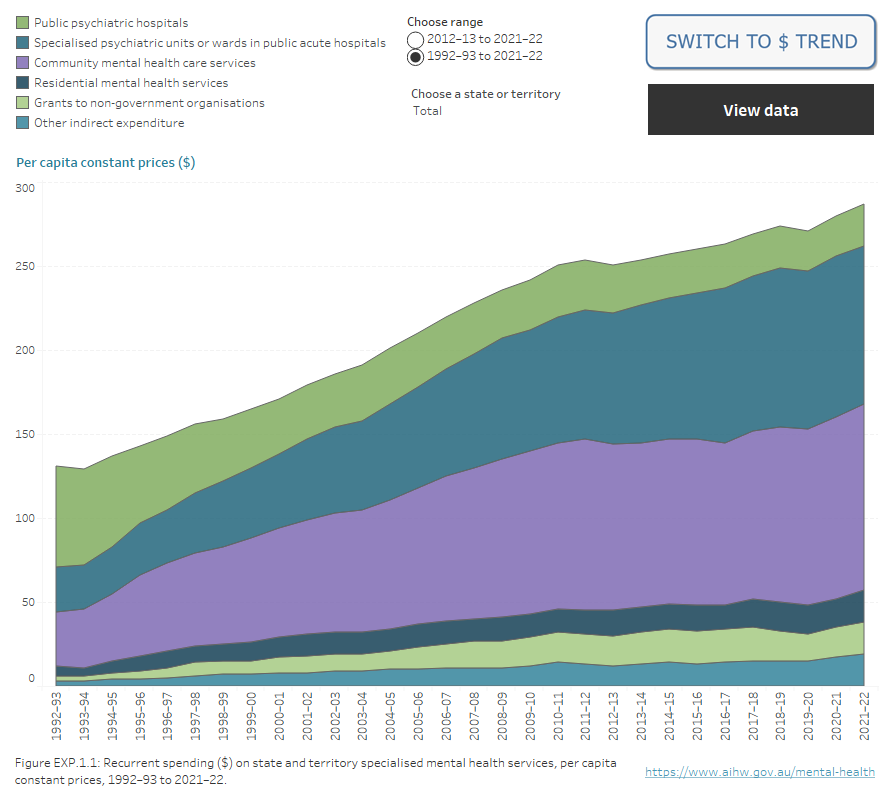

Spending on state and territory specialised mental health services increased from $6.6 billion in 2017–18 to $7.4 billion in 2021–22 in real terms. The largest components of spending in 2021–22 were community mental health care services ($2.8 billion) and public acute hospitals with a specialist psychiatric unit or ward ($2.4 billion). Other spending included public psychiatric hospitals ($0.6 billion), grants to non-government organisations ($0.5 billion) and residential mental health services ($0.5 billion).

Notably, between 1992–93 to 2021–22, spending on public psychiatric hospitals has decreased while increasing for specialised psychiatric units of wards in public hospitals, community mental health care services, residential mental health services, grants to non-government-organisations and other indirect expenditure (Refer to Figure EXP.1).

Figure EXP.1: Recurrent spending ($) per capita on state and territory specialised mental health services, constant prices, 1992–93 and 2011–12 to 2021–22

Stacked area chart showing recurrent spending on specialised mental health services from 1992–93 to 2021–22 and 2012–13 to 2021–22. Spending data can be displayed by constant price or per capita constant price ($) for date ranges, starting from either 2012–13 or 1992–93, to 2021–22 and by state and territory, as well as nationally. Total spending per capita has increased in all areas, with the exception of public psychiatric hospitals which has trended downward.

Note: Non-Commonwealth Australian Capital Territory data for 2021–22 was not available at the time of publication. Updated data for ACT will be published when available. National total calculations for State and Territory jurisdictional (non-Commonwealth) expenditure for 2021–22 do not include ACT data. Caution should be exercised when conducting time series analysis.

Source: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, National Survey of Mental Health Services Database (1992–93 to 2004–05), National Mental Health Establishments Database (2005–06 onwards); Tables EXP.3 and EXP.4.

Per capita spending on specialised mental health services ranged from $263 per capita in Queensland to $421 in the Northern Territory, with a national average of $286 during 2021–22.

Per capita spending on state and territory specialised mental health services increased by an average annual rate of 2% between 2017–18 and 2021–22 in real terms, an increase of about $18 per capita.

Detailed spending data cover 29 years from 1992–93 to 2021–22 (refer to Table EXP.4). Figure EXP.1 shows the changes in state and territory spending patterns due to changes in the service profile mix over time, for example, increased investment in community mental health care services. Further information can be found in Specialised mental health care facilities.

Who funds specialised mental health services?

In 2021–22, the majority (97% or $7.1 billion of the $7.4 billion total cost) of funding for state and territory specialised mental health services was through state or territory governments. However, this estimate does not take into account Australian Government payments to jurisdictions (such as through the National Health Reform Agreement) for the running of public hospital services, including the community-based services managed by public hospitals. Refer to the data source section for technical information regarding Australian Government expenditure.

Public sector specialised mental health hospital services

The $3 billion of spending on public sector specialised mental health hospital services during 2021–22 equates to an average cost per patient day of $1,438. The Northern Territory ($1,989) had the highest average cost per patient day and Queensland ($1,227) the lowest.

Spending can be further described using target population (General, Child and adolescent, Youth, Older person and Forensic target groups), program type (acute and non-acute) or a combination of these.

Mental health services classified as having a General target population accounted for the majority of spending for public sector specialised mental health hospital services during 2021–22 ($2.2 billion or 73%). Child and adolescent services had the highest costs per patient day ($2,653), continuing a long-term trend of these services costing more to run than services with a General ($1,413), Older person ($1,304) or Forensic ($1,413) target population.

There was an average annual increase in spending per patient day of 4% for Child and adolescent, 3% for General, 4% for Older person, and 2% for Forensic services between 2017–18 and 2021–22, in real terms.

Average patient day costs for acute public sector specialised mental health hospital services at the national level were higher than non-acute services for General ($1,510 and $1,060), Older person ($1,315 and $1,243) and Forensic ($1,635 and $1,232) population categories in 2021–22. Child and adolescent had higher average patient day costs for non-acute services ($2,686) than acute services ($2,650) in 2021–22.

Community mental health care services accounted for about $2.8 billion in spending on mental health services during 2021–22, representing about 39% of total state and territory spending.

Of the $485 million state and territory expenditure on residential mental health services during 2021–22, the majority was spent on 24-hour staffed services ($451 million or 93%). General services with 24-hour staffing ($324 million) accounted for two-thirds (67%) of spending.

The average national cost per patient day for residential mental health services was $667 per day in 2021–22. Average costs varied between states and territories, from $440 in Western Australia to $853 in Queensland.

Spending on public sector specialised mental health hospital, community and residential services can be combined and presented by target population. Spending on General services ($282 per capita) was the highest of the target populations during 2021–22, reflecting that many jurisdictions do not have the other specialised target population hospital services. In real terms, spending on General, Child and adolescent and Forensic services had small average annual increases per capita of between 1–2% from 2017–18 to 2021–22, while spending on Youth services increased by an average of 13% per year. During this time, per capita spending on Older person services decreased by an average of 2% per year.

The pandemic has had a range of short-term and ongoing impacts on the Australian health system, including increased spending both in the system overall and specifically for mental health-related care. While mental health-related expenditure increased from about $10.5 billion to $11.6 billion in current prices between 2019–20 to 2021–22, the mental health proportion of total health expenditure over this period decreased from 8% to 7%. This reflects the impact of new spending for health system responses, such as increased use of COVID-19 testing and surveillance systems, increased personal protective equipment and increased cleaning schedules. There were also changes to service delivery during the emergency phase of the pandemic which impacted spending. For example, the Australian Government introduced a range of changes to the MBS to support the provision of care via telehealth, expanding the items included in the MBS and increasing the expenditure from about $1.4 billion in 2019–20 to about $1.6 billion in 2020–21 and 2021–22. In 2020, the Australian Government expanded MBS-subsidised services under the Better Access initiative to provide 10 additional psychological therapy sections. The 10 additional Better Access sessions was discontinued in December 2022. Additionally, the Australian Government temporarily expanded Continued Dispensing arrangement until 30 June 2022. This arrangement allowed pharmacists to dispense up to a one-month supply of most mental health-related PBS medications without a prescription if the medical need was deemed urgent and the medication was previously prescribed. Caution should be exercised when making time series analysis that include the 2020–21 and 2021–22 period.

Private hospital specialised mental health services

In 2021–22, the total revenue from specialised mental health services provided by private hospitals was $789 million. The non-Commonwealth sourced component of this revenue was about $590 million. This represents an annual average increase from 2017–18 of 0% for both. Total recurrent expenditure on specialised mental health services in private hospitals has not been available since 2017–18 due to changes in data collection availability.

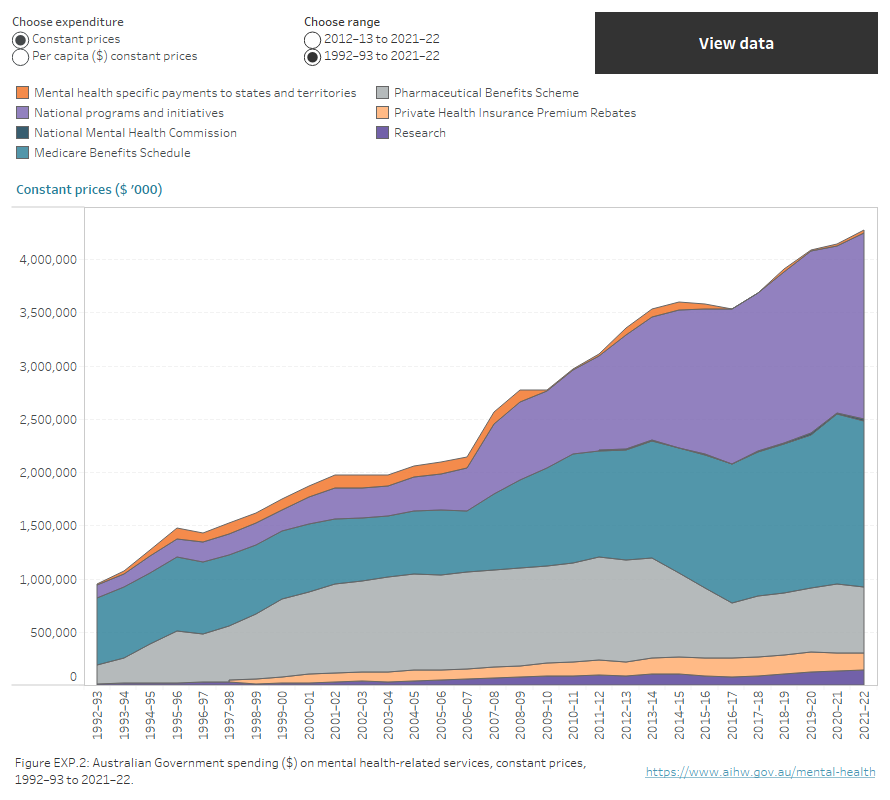

Australian Government expenditure on mental health-related services

Australian Government spending on mental health-related services was estimated to be about $4.3 billion in 2021–22. However, as noted previously and detailed in the data source section of this page, there are other known Australian Government outlays attributable to supporting mental health issues not included in this estimate.

Australian Government spending on mental health-related services increased in real terms by an average annual rate of 4% between 2017–18 and 2021–22, an increase from $149 per capita in 2017–18 to $166 in 2021–22. The programs with the largest spending increases per capita in real terms over this period were National programs and initiatives managed by the Department of Health and Aged Care ($11) and Medicare on psychologists/allied health ($6).

Spending on Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services and mental health-related medications provided through the PBS accounted for 51% of the total Australian Government spending in 2021–22 (Figure EXP.2). This was followed by:

- National programs and initiatives managed by the Department of Health and Aged Care (27%)

- the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (7%)

- Private Health Insurance Premium Rebates (4%)

Australian Government spending on Department of Defence-funded mental health programs increased in real terms from $57 million in 2017–18 to $65 million in 2021–22, an annual average increase of 3%. This spending covers a range of mental health programs and services delivered to Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel. When the number of permanent ADF personnel is taken into consideration (59,304 people; Department of Defence 2022) this equates to about $1,095 per permanent ADF member in 2021–22.

Since 2011–12, there has been a decrease in Australian Government spending on PBS mental health-related prescriptions and an increase in spending on Medicare-subsidised services and programs, and national programs and initiatives (refer to Figure EXP.2). In 2020–21, spending on national programs and initiatives managed by the Department of Social Services (DSS) decreased from previous years, largely due to clients transitioning from national programs and initiatives to the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Medication prices can reduce due to a variety of factors (for example, Price Disclosure, statutory price reductions due to patent changes or legislation mandated by the Government to reduce the PBS listed price of drugs). Refer to the Mental health-related prescriptions section and PBS website for more information. Technical information regarding the calculation of these figures can be found in the data source section.

Figure EXP.2: Australian Government spending ($) per capita, on mental health-related services, constant prices, 1992–93 to 2021–22

Stacked area chart showing spending by the Australian Government on specialised mental health services between 2011–12 to 2021–22 and 1992–93 and 2021–22. Spending data can be displayed as constant price or per capita constant price ($) for date ranges, starting from either 2011–12 or 1992–93, to 2021–22. Expenditure increased for Mental health-specific payments to states and territories, National programs and initiatives, the National Mental Health Commission and private health insurance premium rebates. Expenditure decreased for the Pharmaceuticals Benefit Scheme and research.

Note: National programs and initiatives include programs managed by the Department of Health and Aged Care (the department), programs managed by the Department of Social Services (DSS), programs managed by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), the Department of Defence (DoD) funded programs, Indigenous social and emotional wellbeing programs, National Suicide Prevention Program.

Source: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (unpublished); Table EXP.31

Australian Government expenditure on Medicare mental health services (MBS)

Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services refers to the mental health-specific services subsidised by the Australian Government through the Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS). These services include mental health-specific services provided by psychiatrists, general practitioners (GPs), psychologists and other allied health professionals and are defined in the MBS.

In 2022–23, about $1.5 billion was paid in benefits for Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services. Among this, $1.2 billion (4% of the total Medicare spending) was paid in benefits for Better Access MBS items. Services provided by psychologists were the largest proportion of national spending ($762 million or 49%).

In real terms, spending on Medicare-subsidised services increased from an average of $56 per capita in 2018–19 to $58 in 2022–23, an average annual increase of 1%.

Australian Government expenditure on mental health-related subsidised prescriptions (PBS)

In 2022–23, Australian Government spending on mental health-related subsidised prescriptions under the PBS and RPBS was $672 million, or $26 per capita. Prescriptions for Antipsychotics (40%) and Antidepressants (33%) accounted for the majority spending in 2022–23.

In considering these results, it should be noted that they do not include medications funded through the Aboriginal Health Services program and so is an underestimate of total spending on medicines. Further information can be found in Mental health-related prescriptions.

Spending on PBS/RPBS medications ranged from $33 per capita in Tasmania to $16 in the Northern Territory. For most states and territories, the spending on Antipsychotics was the largest proportion of PBS/RPBS spending, followed by Antidepressants.

Almost three-quarters (71% or $474 million) of spending on mental health-related subsidised prescriptions was for prescriptions issued by GPs.

In real terms, spending on mental health-related prescriptions increased between 2018–19 and 2022–23 from $611 million to $662 million. The total expenditure on subsidised mental health-related prescriptions grew at an annual average rate of about 2% per year over this period. Medication prices can change for a variety of reasons (for example, Price Disclosure); refer to the Mental health-related prescriptions section for more information.

About two-thirds (67% or $426 million) of spending on mental health-related subsidised prescriptions was for prescriptions issued by GPs.

In real terms, spending on mental health-related prescriptions increased between 2017–18 and 2021–22, from $549 million to $630 million. The subsidised and total number of mental health-related prescriptions grew at annual average rates of about 4% per year respectively over this period (refer to table PBS.3). Medication prices can change for a variety of reasons (for example, Price Disclosure); refer to the Mental health-related prescriptions section for more information.

Where can I find more information?

The National Mental Health Commission’s 2014 Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services (NMHC 2014) used a broad methodology to estimate Australian Government expenditure on mental health. The methodology included mental health-related costs, such as the Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment and Carer Allowance. The Australian Government mental health-related expenditure in 2012–13 was estimated to be $9.6 billion, compared with $2.8 billion (current price) using the methodology employed in this publication, as outlined in the Data source section. More recently, the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into Mental Health examined the costs to governments, individuals and insurers of mental healthcare and related services, including broader services such as housing, employment, and education as well as expenditure on treatment, research, and promotion and prevention. The Productivity Commission estimated this cost in 2018–19 was $16 billion (noting this includes only the estimated costs for mental health care and related services) (Productivity Commission 2020), compared with almost $10.6 billion (current price) on this page.

Data validation

Data presented in this publication are the most current data for all years presented. The validation process scrutinises the data for consistency in the current collection and across historical data. The validation process applies rules to the data to test for potential issues. Jurisdictional representatives respond to each issue before the data are accepted as the most reliable current data collection. This process may highlight issues with historical data. In such cases, historical data may be adjusted to ensure data are more consistent. Therefore, comparisons made to previous versions of the AIHW’s mental health publications should be approached with caution.

National Mental Health Establishments Database

Collection of data for the Mental Health Establishments (MHE) National Minimum Data Set (NMDS) began on 1 July 2005, replacing the Community Mental Health Establishments NMDS and the National Survey of Mental Health Services. The main aim of the development of the MHE NMDS was to expand on the Community Mental Health Establishments NMDS and replicate the data previously collected by the National Survey of Mental Health Services. The National Mental Health Establishments Database is compiled as specified by the MHE NMDS.

Scope of the MHE NMDS

The scope of the MHE NMDS includes all specialised mental health services managed or funded, partially or fully, by state or territory health authorities. Specialised mental health services are those with the primary function of providing treatment, rehabilitation or community health support targeted towards people with a mental disorder or psychiatric disability. These activities are delivered from a service or facility that is readily identifiable as both specialised and serving a mental health care function.

The MHE NMDS data are reported at several levels: state, regional, organisational and individual mental health service unit. The data elements at each level in the NMDS collect information appropriate to that level. The state, regional and organisational levels include data elements for revenue, grants to non-government organisations and indirect expenditure. The organisational level also includes data elements for salary and non-salary expenditure, numbers of full-time-equivalent staff and mental health consumer and carer worker participation arrangements. The individual mental health service unit level comprises data elements that describe the function of the unit. Where applicable, these include target population, program type, number of beds, number of accrued patient days, number of separations, number of service contacts and episodes of residential care. In addition, the service unit level also includes salary and non-salary expenditure and depreciation.

Data Quality Statements for National Minimum Data Sets (NMDSs) are published annually on the Metadata Online Registry (METEOR). Statements provide information on the institutional environment, timelines, accessibility, interpretability, relevance, accuracy and coherence. Refer to the Mental Health Establishments NMDS 2020–21: National Mental Health Establishments Database, 2023; Quality Statement.

Rate calculations

Calculations of rates for target populations are based on age-specific populations as defined by the MHE NMDS metadata and outlined below:

- General services: persons aged 18–64

- Child and adolescent services: persons aged 0–17

- Youth services: persons aged 16–24

- Older persons: persons aged 65 and over, and

- Forensic services: persons aged 18 and over.

As the ages included in the target population groups overlap, the rates for the target populations cannot be summed to generate the total rate.

Crude rates were calculated using the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimated resident population (ERP) at the midpoint of the data range (for example, rates for 2021–22 data were calculated using ERP at 31 December 2021). Historical rates have been recalculated using revised ERPs, as detailed in the online technical information.

New South Wales CADE and T–BASIS services

All New South Wales Confused and Disturbed Elderly (CADE) 24-hour staffed residential mental health services were reclassified as specialised mental health non-acute admitted patient hospital services, termed Transitional Behavioural Assessment and Intervention Service (T-BASIS), from 1 July 2007. All data relating to these services have been reclassified from 2007–08 onwards, including number of services, number of beds, staffing and expenditure. Comparison of data over time should therefore be approached with caution.

New South Wales HASI Program

New South Wales has been developing the Housing Accommodation Support Initiative (HASI) since it was established in 2002. This model of care is a partnership program between NSW Ministry of Health, Housing NSW and the non-government organisation (NGO) sector that provides housing linked to clinical and psychosocial rehabilitation services for people with a range of levels of psychiatric disability.

More recently, in 2016 Community Living Supports (CLS) commenced to support more people with severe mental illness to access the same type of support provided in HASI.

Both HASI and CLS are reported as Specialised mental health service – supported mental health housing places. These programs are out of scope as Residential mental health care services.

Private Health Establishments Collection

From 1992–93 to 2016–17 (excluding 2007–08) the ABS conducted a census of all private hospitals licensed by state and territory health authorities and all freestanding day hospitals facilities approved by the Department of Health and Aged Care. As part of that census, data on the staffing, finances and activity of these establishments were collected and compiled in the Private Health Establishments Collection (PHEC). Additional information on the PHEC can be obtained from the ABS publication Private hospitals, Australia (ABS 2018).

Data definitions

The data definitions used in the PHEC are largely based on definitions in the National Health Data Dictionary (NHDD) published on the AIHW’s Metadata Online Registry (METEOR) website (AIHW 2015). The ABS defines private psychiatric hospitals as those licensed or approved by a state or territory health authority and which cater primarily for admitted patients with psychiatric, mental or behavioural disorders (ABS 2018). This is further defined as those hospitals providing 50% or more of the total patient days for psychiatric patients. This definition can be extended to include specialised units or wards in private hospitals, consistent with the approach in the public sector. For further technical information, refer to the Private psychiatric hospital data section of the National Mental Health Report 2013 (Department of Health and Ageing 2013).

Caution is required when comparing the ABS data for 2011–12 onwards to earlier years because the survey was altered in 2010–11 such that psychiatric units could no longer be separately identified from alcohol and drug treatment units. Therefore, the data for beds, patient days, separations and staffing from 2011–12 onwards are estimates based on reported 2010–11 data and trends observed in previous years. Data from the Private Mental Health collection suggest that these data may be underestimates.

The PHEC was discontinued in 2016–17.

Private Psychiatric Hospitals Data Reporting and Analysis Service

The Australian Private Hospitals Association (APHA) Private Psychiatric Hospitals Data Reporting and Analysis Service (PPHDRAS), previously known as the Private Mental Health Alliance Centralised Data Management Service (PMHA CDMS), was launched in Australia in 2001 to support private hospitals with psychiatric beds to routinely collect and report on a nationally agreed suite of clinical measures and related data for the purposes of monitoring, evaluating and improving the quality of and effectiveness of care. The PPHDRAS works closely with private hospitals, health insurers and other funders (e.g., Department of Veterans’ Affairs) to provide a detailed quarterly statistical reporting service on participating hospitals’ service provision and patient outcomes.

PPHDRAS objectives

The PPHDRAS fulfils two main objectives. Firstly, it assists participating private hospitals with implementation of their National Model for the Collection and Analysis of a Minimum Data Set with Outcome Measures. Secondly, the PPHDRAS provides hospitals and private health funds with a data management service that routinely prepares and distributes standard reports to assist them in the monitoring and evaluation of health care quality. The PPHDRAS also maintains training resources for hospitals and a database application which enables hospitals to submit de-identified data to the PPHDRAS, which is analysed and presented in an annual statistical report. In 2021–22, the PPHDRAS financially accounted for 98% of all private psychiatric beds in Australia (PPHDRAS 2023).

From 2017–18, all private hospital data is sourced from the PPHDRAS. Data on expenditure and staffing (Full Time Equivalent) are not collected in PPHDRAS.

In previous years, estimates of expenditure on specialised mental health services in private hospitals were derived from the annual Private Health Establishment Collection (PHEC) undertaken annually by the ABS. PHEC was discontinued after 2016–17. Commencing 2017–18, estimates of private psychiatric hospital care are based on the PPHDRAS, a collection jointly funded by the Australian Private Hospitals Association and the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

Australian Government expenditure on mental health-related services

The Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care annually compiles the total Australian Government expenditure on mental health-related services. This practice was initiated in 1992–93 for publication in the National Mental Health Report which continued through to 2013 as the final publication year, and subsequently incorporated in related reports. Estimated expenditure reported in table EXP.31 of this report covers only those areas of expenditure that have a clear and identifiable mental health purpose. A range of other expenditure, which may be either directly or indirectly related to the provision of support for people affected by mental illness, is not covered in this table. Broadly, this covers:

- programs and services principally targeted at providing assessment, treatment, support or other assistance to people affected by mental ill health

- population-level programs that have as their primary aim the prevention of mental illness or the improvement of mental health and well-being

- research with a mental health focus.

Expenditure that can be directly linked to mental health service provision, but not counted in the spending estimates includes:

- An estimated mental health share of Australian Government payments made to states for the running of public hospitals provided through the non-specific 'base grants' provided to states and territories under the former:

- Medicare Agreements (1993–1998)

- Australian Health Care Agreements (1998–2003, 2003–2009)

- National Healthcare Agreements (2009–2012).

For the years indicated, most state and territory mental health services were delivered through public hospitals and made up about 10% of state/territory-run health services, it is reasonable to assume they benefitted from Australian Government funding contributions. However, estimates have not been included in reporting for historical reasons – principally because payments were not specifically tagged for mental health purposes and therefore fell outside the definition of ‘mental health-specific’ services when decisions were made about how Australian Government funding contributions would be attributed across the two levels of government.

- From 2012–13, Australian Government contributions for state and territory public hospital services paid under the former Medicare Agreements, Australian Health Care Agreements and National Healthcare Agreements were replaced by new arrangements under the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA). These arrangements include grants and activity-based payments specifically tied to the operation of specialist mental health services delivered by state and territory-managed public hospitals. While the quantum of funding made for mental health-specific services under the NHRA is significant and identifiable, expenditure of those funds continues to be attributed to states and territories on the basis of their role as system managers of Australia’s public hospital services.

- From 2006–07, the costs of GP-provided mental health care delivered with MBS general consultation items rather than the mental health-specific items introduced to the MBS in November 2006. Refer to the section ‘Medicare Benefits Schedule – general practitioners’ below for further details.

- An estimated mental health share of Australian Government payments to states and territories for sub-acute mental health services made under the National Partnership Agreement – Improving Public Hospital Services (2009–2014). Although mental health sub-acute beds represented 16% of the growth funded under the Agreement, program specific expenditure was not tracked under the NPA reporting arrangements preventing mental health estimates being distinguished from payments for other categories of sub-acute beds. As a broad estimate however, the mental health component of the Agreement represented approximately $175 million over the period 2010–11 to 2013–14.

- Australian Government subsidies paid to nursing homes and hostels provided for mental health-related care in nursing homes.

- All administrative overheads associated with administration of the mental health items within the MBS and PBS (Note: administrative costs associated with the Department of Health and Aged Care's mental health policy and program management areas are included).

Mental health-related costs for support packages delivered under the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) are also currently excluded from estimates of Australian Government expenditure. A staged implementation of the NDIS began in July 2013. People with a psychiatric disability who have significant and permanent functional impairment are eligible to access funding through the NDIS. In addition, people with a disability other than a psychiatric disability, may also be eligible for funding for mental health-related services and support if required.

In addition, the Australian Government provides significant support to people affected by mental illness through income security provisions and other social and welfare programs. Consistent with the focus on mental health-specific expenditure, these costs have been excluded from the analysis.

The following detailed notes on how estimates specific to Australian Government mental health-specific expenditure have been revised in consultation with the Department of Health and Aged Care, building on those described in Appendix 11 of the National Mental Health Report 2010 (Department of Health and Ageing 2010).

Mental health-specific payments to states and territories

For years up to 2008–09, this category covers specific payments made to states and territories by the Australian Government for mental health reform under the Medicare Agreements 1993–1998, and Australian Health Care Agreements 1998–2003 and 2008–09. From July 2009, the Australian Government provided funding through Specific Purpose Payments (SPP) to state and territory governments under the National Healthcare Agreement (NHA) that do not specify the amount to be spent on mental health or any other health area. Therefore, specific mental health funding cannot be identified under the NHA.

From 2008–09 onwards, the amounts include:

- National Partnership Agreement – National Perinatal Depression Plan – Payments to States, ending 30 June 2015

- National Partnership Agreement – Supporting Mental Health Reform, commencing 2011–12

- National Partnership Agreement – Improving Health Services in Tasmania (Innovative flexible funding for mental health), commencing 2012–13.

Nil payments are shown from 2016–17 as all three National Partnerships were completed by 2015–16.

For 2020–21 the amounts shown include:

- Project Agreement for Suicide Prevention

- Project Agreements for the Community Health and Hospitals Program initiatives for Eating Disorder Treatment Centres in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania, and Youth Mental Health and Suicide Prevention in the Australian Capital Territory

- Project Agreement for Grace’s Place in New South Wales

- Project Agreement for the South Australian Adult Mental Health Centre.

The expenditure reported here excludes payments to states and territories for the development of sub-acute mental health beds made under Schedule E of the National Partnership Agreement – Improving Public Hospital Services, which totalled $175 million over the period 2010–11 to 2013–14. Mental health-specific payments cannot be separately identified from payments for other categories of sub-acute beds made to states and territories.

The data under this item do not include Department of Veterans’ Affairs payments to states and territories for public hospital mental health services delivered to veterans and other eligible recipients. These costs are included under the item ‘National programs and initiatives (DVA managed)’.

National program and initiatives (Department of Health and Aged Care managed)

Initiatives funded through national mental health reform funding provided under special appropriations linked to the Australian Health Care Agreements (excluding amounts reported against Mental health-specific payments to states and territories above).

- For years up to 2005–06, this covers the following categories of Australian Government spending:

- National Mental Health Program

- National Depression Initiative (beyondblue)

- More Options Better Outcomes (ATAPS)

- Kids Helpline – one off grant 2003–04

- Youth mental health (headspace)

- Program of Assistance for Survivors of Torture and Trauma

- OATSIH Social & Emotional Wellbeing Action Plan

- Departmental costs.

- From 2006–07 onwards, programs include the above plus new Department of Health and Aged Care-administered measures funded by the Australian Government under the COAG Action Plan on Mental Health 2006 (excluding MBS expenditure through Better Access) and additional measures introduced in subsequent Federal Budgets. Programs added to the category are:

- Alerting the Community to Links between Illicit Drugs and Mental Illness

- New Early Intervention Services for Parents, Children and Young People

- Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists, GPs - Education and Training component

- New Funding For Mental Health Nurses (Mental Health Nurse incentive program)

- Support for Day to Day Living program

- Mental Health Services in Rural and Remote Areas

- Improved Services for People with Drug and Alcohol Problems and Mental Illness

- Funding for Telephone Counselling, Self-help and Web based Support Programmes

- Mental Health Support for Drought Affected Communities Initiative

- Additional Education Places, Scholarships and Clinical Training in Mental Health - Scholarships and Clinical Training components only

- Mental Health in Tertiary Curricula

- National Perinatal Depression initiative (excluding mental health-specific payments to states and territories included above)

- Expansion of Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centres

- Partners In Recovery Program

- Leadership in Mental Health Reform.

Some of these programs were time limited and do not apply to all data presented on this page.

More recently, there has been a consolidation of Department of Health and Aged Care Mental Health Program funding into a reduced set of categories, arising largely from the Australian Government response to the 2014 National Mental Health Commission Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services. Direct spending on mental health- related programs is split into 5 broad program areas: national leadership; primary mental health care services; promotion, prevention and early intervention; psychosocial support; and suicide prevention (below). Over half of the Mental Health Program funding is provided to Primary Health Networks to plan and commission mental health services at a regional level.

Note also that the category excludes expenditure on the National Suicide Prevention Program which is reported separately in the relevant expenditure tables of Australian Government spending. While managed by the Department this is reported separately.

Expenditure reported under the item 'Indigenous social and emotional wellbeing programmes' has previously been reported under 'National programs and initiatives (Department of Health and Aged Care managed)'. This expenditure is now separately reported following the transfer of the former OATSIH Social and Emotional Wellbeing program to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the National Indigenous Australians Agency. Adjustments have been made to all years.

National program and initiatives (DSS managed)

Spending on Department of Social Services (DSS) managed programs commenced with three measures introduced in 2006–07 through the COAG Action Plan on Mental Health (Personal Helpers and Mentors, Mental Health Respite, Family Mental Health Support Services). Subsequently several additional new measures have been added from Federal Budgets that are managed through the DSS portfolio and are included in expenditure reporting (‘A Better Life’, ‘Carers and Work’, and ‘Individual Placement and Support Trial’). DSS has advised that, from 2016–17, two programs (Personal Helpers and Mentors, Mental Health Respite Care) began transitioning to the NDIS and, expenditure reported for these programs is inclusive of funding transferred to the NDIS.

From 2020–21, most funding transferred from DSS to the National Disability Insurance Agency for clients that transitioned to the NDIS. The Carers and Work pilot program ceased in June 2019.

National programs and initiatives (DVA managed)

Reported spending by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) includes Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure, Repatriation Medical Benefits expenditure on general practitioners, psychiatrists and allied health providing mental health care, payment for mental health care provided in public and private hospitals for veterans, grants to Phoenix Australia and expenditure on OpenArms and related mental health programs. Note that estimated expenditure on mental health-related Pharmaceuticals includes the costs of anti-dementia drugs for years up to and including to 2009–10 but these have been removed for subsequent years.

DVA provided the following information in respect of its mental health-related expenditure in 2021–22:

| 2021–22 ($M) (a) |

|---|---|

Private hospitals(b)(c)(d) | 60.3 |

Public hospitals(b) | 38.7 |

Consultant psychiatrists | 26.5 |

OpenArms (previously Veterans and Veterans’ Families Counselling Service) | 109.6 |

Pharmaceuticals(e) | 17.3 |

Private psychologists and allied health | 37.3 |

General practitioners | 15.5 |

Phoenix Australia (previously Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health) | 2.0 |

Veterans' mental health care – improving access for younger veterans | - |

Other programs | - |

Total | 307.2 |

Notes: (a) Expenditure is indicative as not all data sets are fully complete. Small variations may be expected over time.

(b) Based only on payments made for patients classified to Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) 19 (Mental Diseases and Disorders) under the Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG) classification system. Excludes payments made for patients classified to MDC 20 (Alcohol/drug use and alcohol/drug induced organic mental disorders).

(c) Private hospital figure includes payments to the hospital only (i.e., any other payments during these episodes such as payments to doctors have been excluded).

(d) DVA depends on submitted Hospital Casemix Protocol data from private hospitals and Diagnostic Procedure Combinations to obtain correct MDC and diagnosis information. When this information is not available (e.g., provided by hospitals on a quarterly basis and most recent quarter’s data not yet received) then an understatement can occur in reporting. For this report, and only in relation to private psychiatric facilities, billing item codes have been used to identify and include mental health data in this category.

(e) Excludes anti-dementia drugs.

Department of Defence-funded programs

Spending by the Department of Defence covers a range of mental health programs and services delivered to Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel, as of 2009–10 onwards; data for prior years is unavailable. Increased expenditure over the period reflects, in part, increased accuracy of data capture. Details of the ADF Mental Health Strategy are available at the Department of Defence website.

The Department provided the following information in respect of its mental health-related expenditure in 2021–22:

| 2021–22 ($M) (a) |

|---|---|

JHC Direct Mental Health Program and Implementation Costs | 1.1 |

Mental Health Personnel Costs | 7.7 |

FFS Garrison Psychology Services | 16.0 |

FFS Garrison Psychiatrist Services | 8.6 |

Mental Health Treatment Programs | 11.7 |

Contracted General Practitioner Costs [a] | 7.8 |

Contracted Mental Health Professionals | 11.5 |

MIMS Dispensed Therapeutic Classification Drugs | 0.6 |

Total | 65.0 |

Note: (a) Represents the methodology whereby 10% of a Contracted General Practitioners consultations relate to mental health.

National Suicide Prevention Program

This program commenced in 1995–96 as the National Youth Suicide Prevention Strategy but was broadened in later years. Reported expenditure includes all Australian Government allocations made under the national program, including additional funding made available under the COAG Action Plan and subsequent Federal Budgets. Changes in administrative arrangements and financial reporting make the estimates from 2015–16 not directly comparable to previous years. Components of the National Suicide Prevention Program are based on estimated expenditure to as closely as possible match the former methodology.

Indigenous social and emotional wellbeing programs

This expenditure refers to two programs:

- The OATSIH Social & Emotional Wellbeing Action Plan program that commenced in 1996–97 following the Bringing Them Home report on the stolen generation of Indigenous children. Up to 2012–13 this program was managed by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care and rolled into the reporting category ‘National program and initiatives (Department of Health and Aged Care managed)’. As part of a realignment of responsibility for Indigenous affairs, the program was transferred to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in 2013–14. Social and emotional wellbeing services and activities receive funding through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy Safety and Wellbeing Programme, administered by the National Australians Indigenous Agency.

- The measure titled ‘Improving the Capacity of Health Workers in Indigenous Communities’ funded under the COAG Action Plan in 2006–07. This measure ceased in 2010–11.

In previous years’ reporting, expenditure on these programmes was included under ‘National program and initiatives (Department of Health and Aged Care managed) ‘. From 2013–14, relevant expenditure is now reported separately, with appropriate adjustments to previous years.

From 2018–19, figures include expenditure for Indigenous Suicide Services, Indigenous Mental Health First Aid, Workforce Development Support Units and Indigenous Youth Connection to Culture.

Medicare Benefits Schedule data

Refer to the Data Source section of the Medicare mental health services section for more information.

Medicare Benefits Schedule–psychiatrists

Reported expenditure refers to benefits paid for all services by consultant psychiatrists processed in each of the index years. Data exclude payments made by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs under the Repatriation Medical Benefits Schedule which are reported in the item National programs and initiatives (DVA managed).

Medicare Benefits Schedule–general practitioners

Reported expenditure includes data for the Medicare-subsidised Better Access to Psychiatrists and Psychologists through the MBS initiative described above and in the Medicare mental health services section. Expenditure on GP mental health care is based solely on benefits paid against MBS mental health-specific GP items, which are predominantly the Better Access GP mental health items plus a small number of other items that were created in the years preceding the introduction of the Better Access initiative. This estimate of mental health-related GP costs is conservative because it does not attempt to assign a cost to the range of GP mental health work that is not billed as a specific mental health item.

Introduction of Better Access

As the Better Access items were introduced in November 2006 and so the 2006–07 data do not represent a full financial year for these specific items.

The data for this item before November 2006 were estimated to be 6.1% of total MBS benefits paid for GP attendances, based on data and assumptions as detailed in the National Mental Health report 2010 (Department of Health and Ageing 2010). To incorporate these changes, GP expenditure reported for 2006–07 was based on total MBS benefits paid against these new items specific to mental health, plus 6.1% of total GP benefits paid in the period preceding the introduction of the new items (July to November 2006).

For future years, all expenditure on GP mental health care is based solely on benefits paid against MBS Better Access mental health items, plus a small number of other items that were created in the years preceding the introduction of the Better Access initiative. The latter group includes items that may be claimed by other medical practitioners. This provides a significantly lower expenditure figure than obtained using the 6.1% estimate of previous year because it does not attempt to assign a cost to the range of GP mental health work that is not billed as a specific Better Access item.

Comparisons of GP mental health-related expenditure reported in Table EXP.19 prior to 2007–08 with subsequent years are therefore not valid as the apparent decrease reflects the different approach to counting GP mental health services.

Data exclude Repatriation Medical Benefits expenditure on general practitioner mental health care which is included in the item National programs and initiatives (DVA managed).

Medicare Benefits Schedule–psychologists/allied health

Spending refers to MBS benefits paid for services provided by clinical psychologists, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists approved by Medicare, for items introduced through the Better Access to Mental Health Care initiative on 1 November 2006. Note that these items commenced 1 November 2006 and were not available for the full 2006–07 period. In 2004, a small number of allied health programs that were introduced under the Enhanced Primary Care program were also included but represent less than 1% of the overall spending reported (Department of Health and Ageing 2010).

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data

Refer to the Data Source section of the Mental health-related prescriptions section for more information.

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

Refers to all Australian Government benefits for psychiatric medication in each of the index years, defined as drugs included in the following classes of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Drug Classification System: antipsychotics; anxiolytics; hypnotics and sedatives; psychostimulants; and antidepressants. In addition, payments include Clozapine dispensed in public hospitals under the Highly Specialised Drug program and funded separately through special arrangements prior to December 2013. The amounts reported exclude payments made by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs under the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule which are included in the item National programs and initiatives (DVA managed).

Private Health Insurance Premium Rebates

Estimates of the ‘mental health share’ of Australian Government Private Health Insurance Rebates are derived from a combination of sources and based on the assumption that a proportion of Australian Government outlays designed to increase public take up of private health insurance have subsidised private psychiatric care in hospitals and other services paid by private health insurers. For illustrative purposes, the methodology underpinning these estimates is described below, sourced from Appendix 11 of the National Mental Health Report 2010 (Department of Health and Ageing 2010).

Private Health Insurance Incentives Scheme

In 1997, the Australian Government passed the Private Health Insurance Incentives Act 1997. This introduced the Private Health Insurance Incentives Scheme (PHIIS) effective from 1 July 1997. Under the PHIIS, fixed-rate rebates were provided to low and middle-income earners with hospital and/or ancillary cover with a private health insurance fund. Those rebates could be taken in the form of reduced premiums (with health funds reimbursed by the Australian Government out of appropriations) or as income tax rebates, claimable after the end of the income year. On 1 January 1999, the means-tested PHIIS was replaced with a 30% rebate on premiums, available to all persons with private health insurance cover. As with the PHISS, the 30% rebate could be taken either as a reduced premium (with the health funds being reimbursed by the Australian Government) or as an income tax rebate (Department of Health and Ageing 2010).

The combined Australian Government outlays under the two schemes, and the estimated amounts spent on private hospital care for 2021–22 are as follows (current prices):

| 2021–22 ($M) |

|---|---|

Total Australian Government outlays on private health insurance subsidies | 6,262 |

Estimated component of Australian Government private health insurance subsidies spent on hospital care | 3,457 |

Source: AIHW 2023.

Estimation of the ‘mental health share’ of the amounts shown at (B) is based on the proportion of total private hospital revenue accounted for by psychiatric care. This assumes that if psychiatric care provided by the private hospital sector accounts for x% of revenue, then x% of the component of the Australian Government private health insurance subsidies spent by health insurance funds in paying for private hospital care is directed to psychiatric care.

A new element introduced from 2015–16 includes an estimate of the PHI Premium Rebates contribution to ancillary benefits paid by private health insurers for private psychologists. All years have been adjusted to include this component.

The previous method for estimating the private hospital activity and revenue relied on data provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics through its Private Health Establishment Collection (PHEC) which was discontinued in 2016–17. Commencing 2017–18, the estimate is based on the Private Psychiatric Hospitals Data Reporting and Analysis Service (PPHDRAS), a collection jointly funded by the Australian Private Hospitals Association and the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, complemented by data from the Private Hospital Data Bureau.

| 2021–22 ($M) |

|---|---|

(A) Estimated component of Australian Government private health insurance subsidies spent on hospital care | 3,457 |

Per cent of total private hospital revenue earned through the provision of psychiatric care | 5% |

(B) Estimated ‘mental health share’ of Australian Government private health insurance subsidies spent on hospital care | 158.4 |

Research

Research expenditure represents the value of mental health-related grants administered by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) or the Department of Health and Aged Care through the Medical Research Future Fund during the relevant year. Data were provided by the NHMRC and the Department of Health and Aged Care. Minor amendments have been made to years preceding 2017–18, with adjustments made to 2017–18 to 2019–20 figures to include Medical Research Future Fund expenditure, which commenced in 2017–18.

Population data

Population estimates used to calculate population rates were sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. Private hospitals, Australia, 2016–17. ABS cat. no. 4390.0. Canberra: ABS.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2015. National Health Data Dictionary version 16.2. Cat. no. HWI 131. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2023. Health expenditure Australia 2021–22. Cat. no. HWE 89. Canberra: AIHW.

Department of Defence 2022. Defence Annual Report 2020–21. Canberra: Department of Defence.

Department of Health and Ageing 2013. National mental health report: tracking progress of mental health reform in Australia, 1993–2011. 1: Commonwealth of Australia.

Department of Health and Ageing 2010. National mental health report 2010: summary of 15 years of reform in Australia’s mental health services under the National Mental Health Strategy 1993–2008. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

SA (Services Australia) 2022. Department of Human Services annual report 2020–21. Canberra: Department of Human Services.

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) 2014. The national review of mental health programmes and services. Sydney: NMHC.

PPHDRAS (Private Psychiatric Hospitals Data Reporting and Analysis Service) (2022) Private Hospital-based Psychiatric Services 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020, accessed 16 January 2024.

Productivity Commission 2020. Mental Health, Report no. 95, Canberra.

Data coverage includes the time period 1992–93 to 2022–23. This page was last updated in February 2024. Australian Government Medicare expenditure and mental health-related medications subsidised under the PBS and RPBS expenditure data for 2022–23 on this page were last updated in April 2024.