Atrial fibrillation

Page highlights:

How many Australians have atrial fibrillation?

- Atrial fibrillation affects approximately 2.2% of the general population – equivalent to more than 500,000 people in 2021.

- In 2020–21, there were around 201,000 hospitalisations where atrial fibrillation recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis.

In 2020–21, atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates were 21% higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas.

Atrial fibrillation contributed to 16,300 deaths (9.5% of all deaths) in 2021.

Atrial fibrillation contributed to 16,300 deaths (9.5% of all deaths) in 2021.

What is atrial fibrillation?

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a disturbance of the electrical system of the heart, where the heart beats with an abnormal rhythm, and does not pump blood regularly or work as efficiently as it should.

Often, people with AF do not know that they have it, and they do not experience any symptoms. Others may experience an irregular pulse, heart palpitations (‘fluttering’), fatigue, weakness, discomfort, shortness of breath or dizziness.

Common causes of AF include long-term high blood pressure, coronary heart disease and valvular heart disease. For some people, there is no apparent cause.

The risk of developing AF is higher in older people. Other risks include obesity, diabetes, CKD, obstructive sleep apnoea, smoking and alcohol consumption above guideline levels.

AF increases the risk of stroke, and strokes associated with AF are more severe with a risk of death twice that of other stroke causes. An individual’s risk may be even higher if their AF is associated with previous heart disease or with other chronic diseases (NHFA 2016).

How many Australians have atrial fibrillation?

Currently, there are no national data sources that report on the total number of Australians living with AF.

Surveys and studies on sections of the Australian population suggest that AF affects approximately 2.2% of the general population – equivalent to more than 500,000 people in 2021 (AIHW 2020).

The proportion affected increases with age. An estimated 5.4% of the Australian population aged 55 and over have AF.

Hospitalisations

Often, AF can be managed through the primary care that is provided by general practitioners, allied health services, community health services and community pharmacy. However, some patients with AF will need admission to hospital for investigation and management, and they may require surgical or therapeutic procedures during the admission.

Note that the hospitalisation data presented here are based on admitted patient episodes of care, which exclude non-admitted emergency department care, but can include multiple events experienced by the same individual.

Atrial fibrillation often occurs alongside other chronic diseases, so both the principal and additional diagnoses of AF should be counted when estimating its contribution to hospitalisations.

There were around 201,000 hospitalisations where AF was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21, at a rate of 785 per 100,000 population. This represents 1.7% of all hospitalisations in Australia.

Atrial fibrillation was recorded as the principal diagnosis in 38% (76,200) of these hospitalisations.

In those cases where AF was listed as an additional diagnosis, common principal diagnoses include other cardiovascular diseases (heart failure, stroke, acute myocardial infarction), pneumonia, sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and fracture of femur (AIHW 2020).

Age and sex

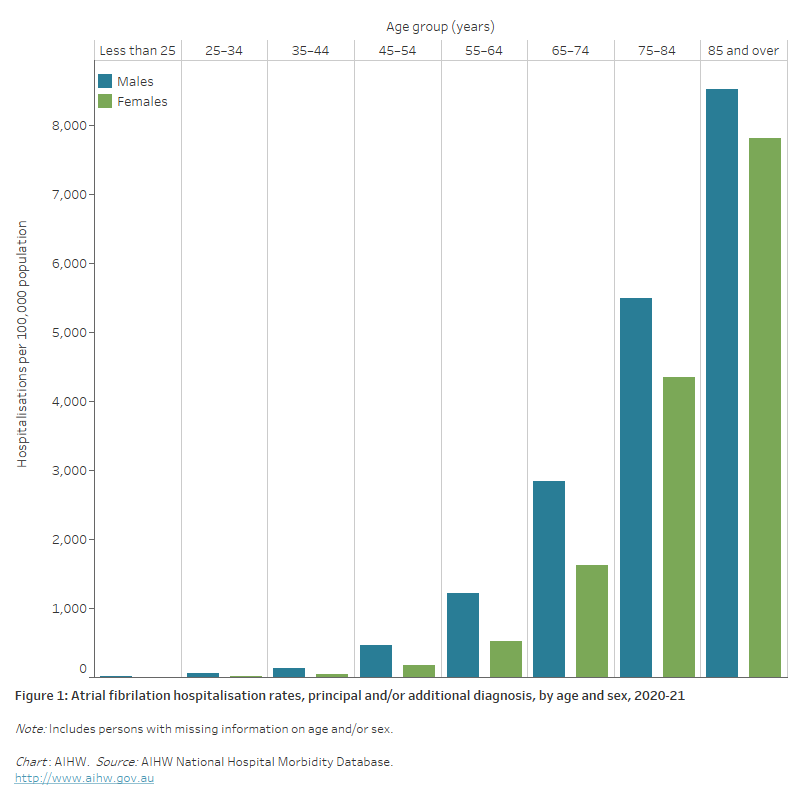

Where AF was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, hospitalisation rates:

- were overall 1.6 times as high for males as females, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher among males than females in all age groups

- increased with age, with rates highest for males and females aged 85 and over – at least 1.6 times as high as those aged 75–84 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows that atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates in 2020–21 were highest among males and females 85 years and over (8,500 and 7,800 per 100,000 population, respectively).

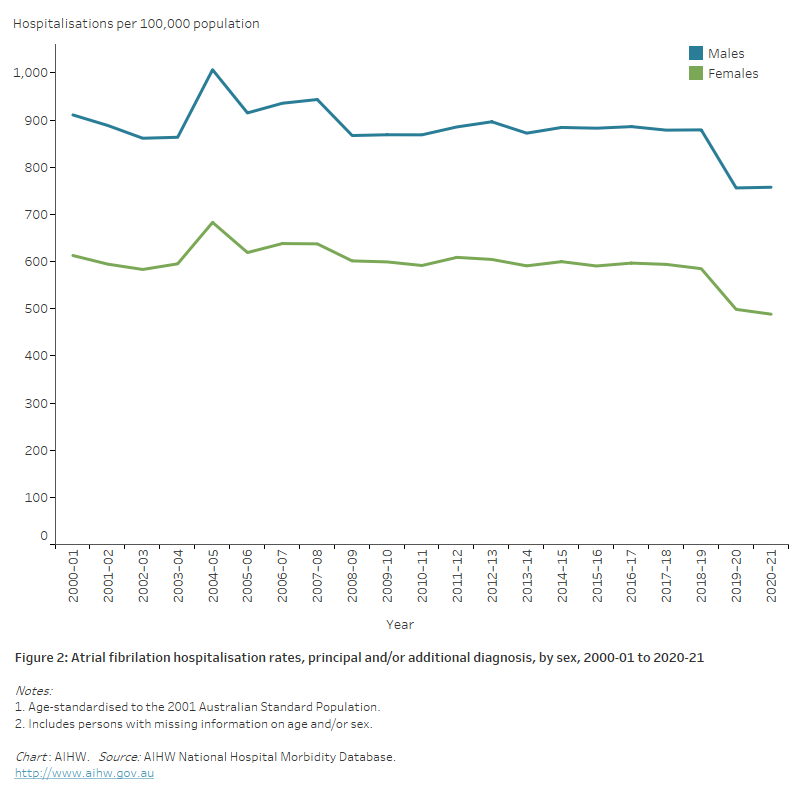

Trends

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21 the age-standardised rate of hospitalisations with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of AF fell from 748 to 618 per 100,000 population.

The number of AF hospitalisations increased by half (53%) for males and 30% for females, while rates fell by 17% for males and 20% for females (Figure 2).

The hospitalisation rate where AF was the principal diagnosis, however, increased by almost 40%, from 175 to 240 per 100,000 population.

The use of linked hospitalisations data in Western Australia has shown that the increase in that state was driven more by repeat hospitalisations for the same person, rather than new hospitalisations (Briffa et al. 2016, Weber et al. 2019).

Figure 2: Atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates between 2000–01 and 2020–21 from 911 to 758 per 100,000 population for males and 613 to 488 per 100,000 population for females.

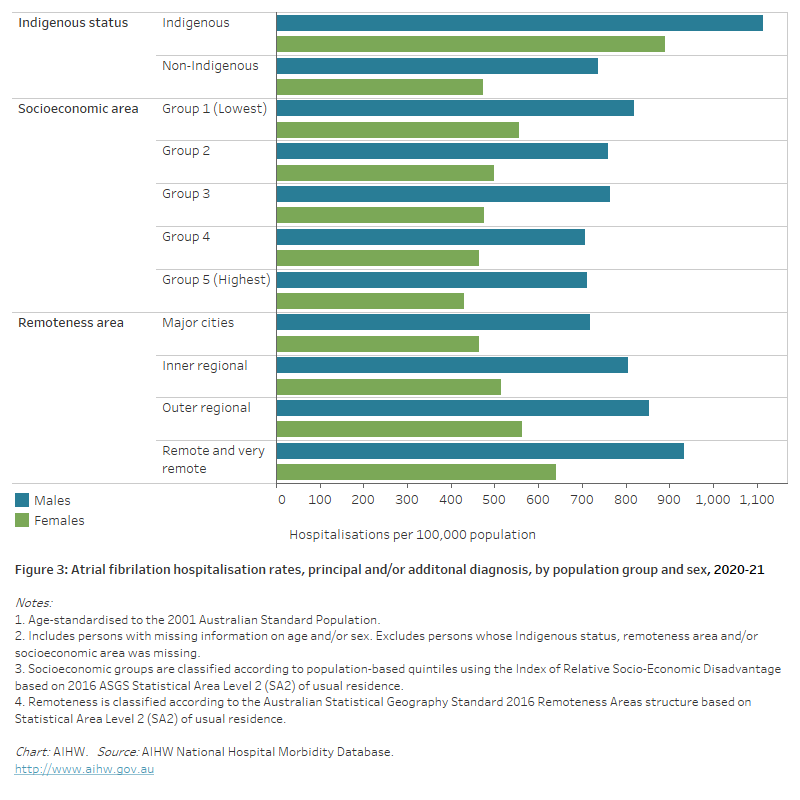

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 4,500 hospitalisations with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of AF among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, at a rate of 518 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 1.7 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate

- the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was greater for females than males – 1.9 times as high for females and 1.5 times as high for males (Figure 3).

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, age-standardised AF hospitalisation rates were 21% higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas.

For males, the gap in hospitalisations between the lowest and highest socioeconomic areas was 1.2 times as high, and for females 1.3 times as high (Figure 3).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, age-standardised AF hospitalisation rates were 36% higher among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those in Major cities.

The disparities in male and female rates were similar – male rates were 1.3 times as high in Remote and very remote areas as in Major cities, while female rates were 1.4 times as high (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows that age-standardised atrial fibrillation hospitalisation rates in 2020–21 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

Deaths

Atrial fibrillation (AF) contributed to 16,300 deaths (9.5% of all deaths) in 2021 – a rate of 63 per 100,000 population.

AF was the underlying cause of 2,400 deaths in 2021, and was an associated cause in a further 13,900 deaths.

AF is far more likely to be listed as an associated cause of death. This is because it is often not AF that leads directly to death – rather, one of its accompanying comorbidities or complications will be listed as the underlying cause of death on the death certificate.

When AF is examined as an associated cause of death, the conditions most commonly listed as the underlying cause of death were other diseases of the circulatory system such as coronary heart disease (CHD) or stroke, as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and dementia (AIHW 2020).

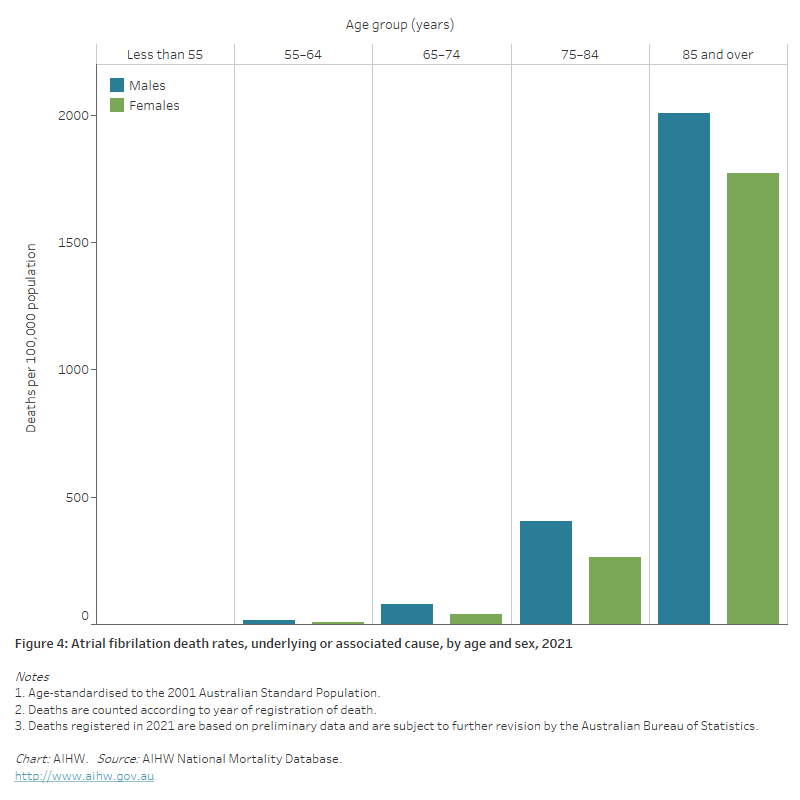

Age and sex

In 2021, death rates for AF as the underlying or associated cause:

- were 1.4 times as high for males as for females after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher for males than females across all age groups

- increased with age, with over 60% of deaths occurring among those aged 85 and over. Atrial fibrillation death rates for males and females in the 85 and over age group were 4.9 times as high for males and 6.7 times as high for females aged 75–84 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Atrial fibrillation death rates, underlying or associated cause, by age and sex, 2021

The bar chart shows that atrial fibrillation death rates in 2021 were highest among males and females 85 and over (2,000 and 1,800 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Trends

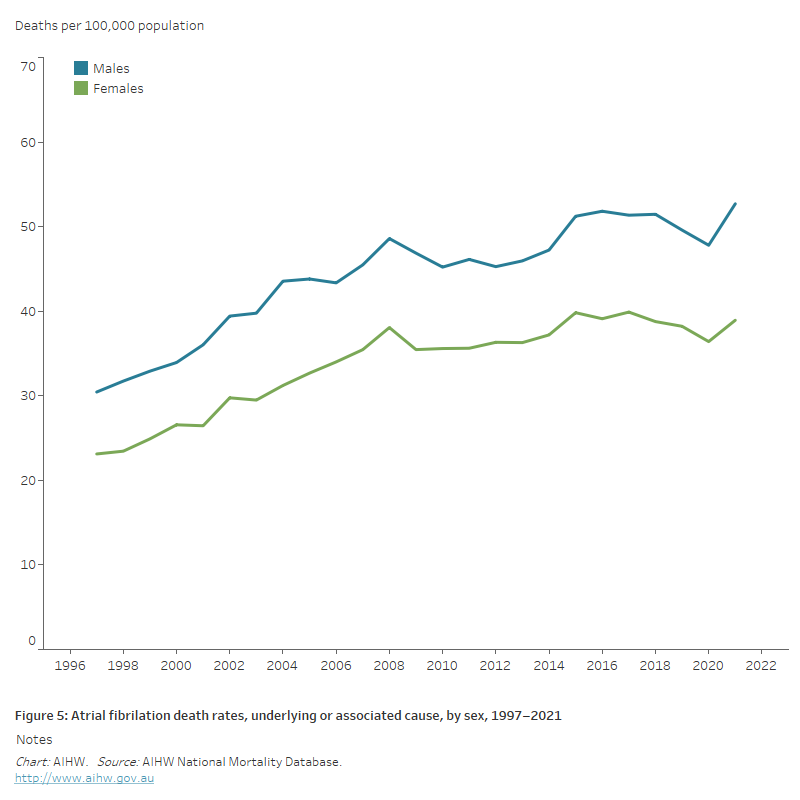

Between 1997 and 2021:

- the number of deaths where AF was an underlying or associated cause increased more than 3-fold, from 4,400 to 16,300

- age-standardised AF death rates increased by 70% – from 30 to 53 per 100,000 population for males, and from 23 to 39 per 100,000 population for females (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Atrial fibrillation death rates, underlying or associated cause, by sex, 1997–2021

The line chart shows the increase in age-standardised atrial fibrillation death rates between 1997 and 2021 for both males and females, from 30 to 53 and 23 to 39 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Variation among population groups

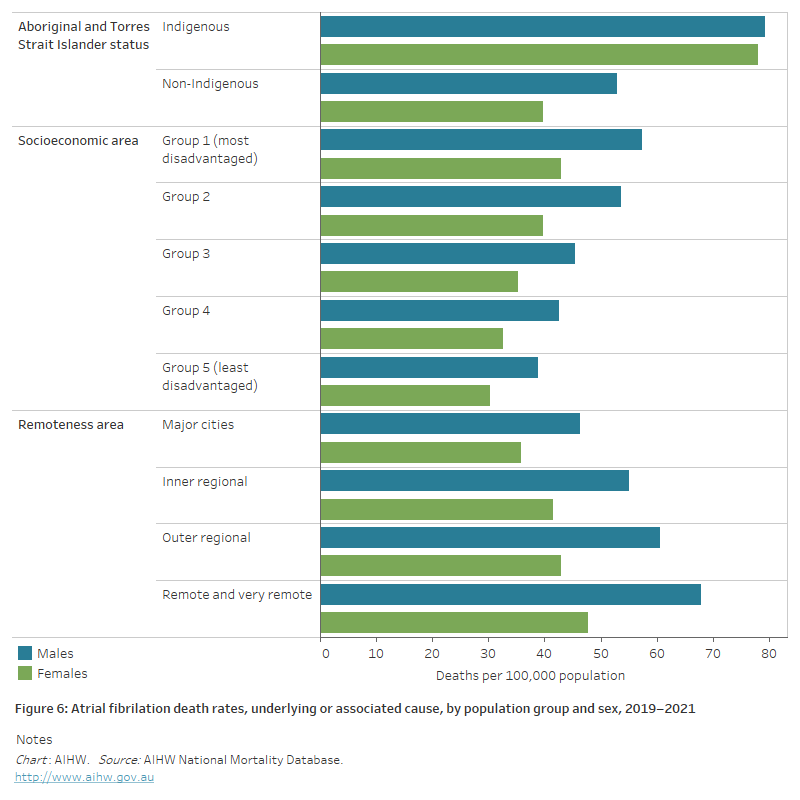

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2019–2021, AF was the underlying or associated cause of death for 557 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the jurisdictions with adequate Indigenous identification, a rate of 24 per 100,000 population.

The age-standardised Indigenous death rate was 1.7 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate . Indigenous males and females had AF death rates 1.5 and 2.0 times as high as non-Indigenous males and females (Figure 6).

Socioeconomic area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised death rate for AF as an underlying or associated cause was 1.5 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The difference was slightly greater for males (1.5 times as high) than females (1.4 times as high) (Figure 6).

Remoteness area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised AF death rate for people living in Remote and very remote areas was 1.4 times as high as for those living in Major cities.

Males had higher AF death rates than females in all remoteness areas (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Atrial fibrillation death rates, underlying or associated cause, by population group and sex, 2019–2021

The horizontal bar chart shows that age-standardised atrial fibrillation death rates in 2019–2021 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

AIHW (2020) Atrial fibrillation in Australia. AIHW cat. no. CDK 17. Canberra: AIHW.

Briffa T, Hung J, Knuiman M, McQuillan B, Chew DP, Eikelboom J, Hankey GJ et al. (2016) Trends in incidence and prevalence of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation and associated mortality in Western Australia, 1995–2010. International Journal of Cardiology 208: 19–25.

NHFA (National Heart Foundation of Australia) (2016) Atrial fibrillation: understanding abnormal heart rhythm. Canberra: NHFA.

Weber C, Hung J, Hickling S, Li I, McQuillan B, Briffa T (2019) Drivers of hospitalisation trends for non-valvular atrial fibrillation in Western Australia, 2000–2013. International Journal of Cardiology 276: 273–7.