Hospital care and procedures

Page highlights:

Hospitalisation for all cardiovascular disease

- In 2020–21, there were 600,000 hospitalisations where cardiovascular disease was recorded as the principal diagnosis.

- In 2020–21, cardiovascular hospitalisation rates were around 40% higher among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those in Major cities.

- In 2020–21, there were 146,000 coronary angiography procedures reported for patients admitted to hospital – 97,200 (67%) for males and 48,900 (33%) for females.

This section provides an overview of hospital care for all cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in the Australian population. For information on hospitalisations for particular CVD subtypes, refer to the relevant page.

A hospitalisation for CVD may be for medical, surgical, or other acute care, for subacute care (for example rehabilitation) or for non-acute care (for example, maintenance care for a person with limitations due to a cardiovascular condition).

Many patients who are hospitalised with acute cardiovascular events will be cared for in a specialist unit:

- in 2021, there were 103 coronary care units in Australian public hospitals and a further 39 cardiac surgery units (AIHW 2022)

- in 2021, there were 93 specialised stroke units (Stroke Foundation 2021).

Hospitalisation for all cardiovascular disease

In 2020–21, there were 600,000 hospitalisations where CVD was recorded as the principal diagnosis. This represented 5.1% of all hospitalisations in Australia in 2020–21.

In 2020–21, there were 600,000 hospitalisations where CVD was recorded as the principal diagnosis. This represented 5.1% of all hospitalisations in Australia in 2020–21.

Of these, 530,000 (90%) were for acute care – that is, care in which the intent is to perform surgery, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures in the treatment of illness or injury).

Of these, 542,000 (90%) were for acute care – that is, care in which the intent is to perform surgery, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures in the treatment of illness or injury).

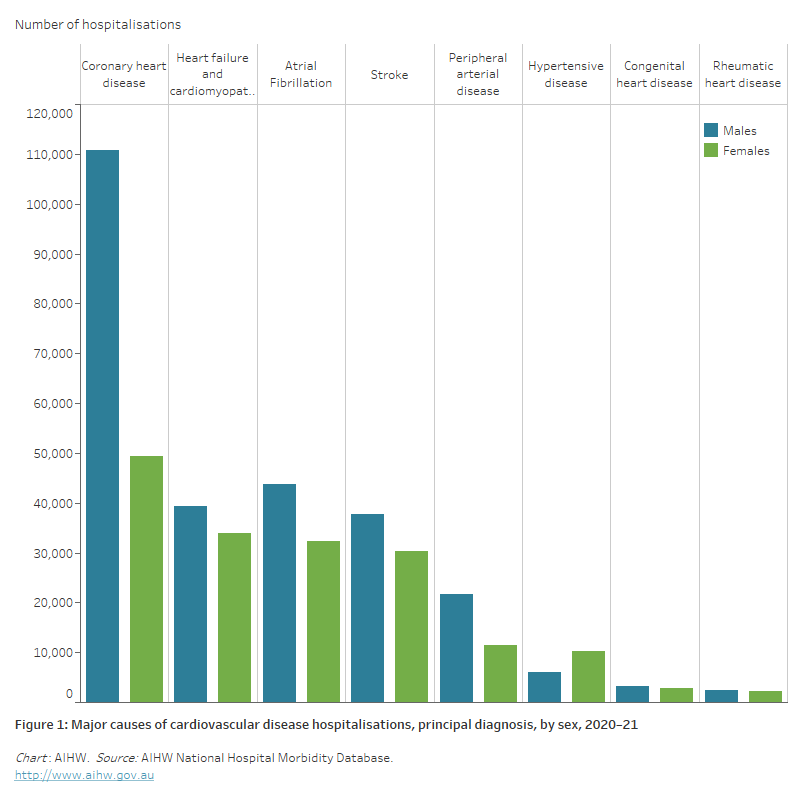

Of all hospitalisations for CVD in 2020–21:

- 27% had a principal diagnosis of coronary heart disease, followed by

- atrial fibrillation (13%)

- heart failure and cardiomyopathy (12%)

- stroke (11%)

- peripheral arterial disease (5.5%)

- hypertensive disease (2.7%)

- rheumatic heart disease (0.8%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Major causes of cardiovascular disease hospitalisations, principal diagnosis, by sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows the number of hospitalisations for selected cardiovascular diseases in 2020–21, ranging from 160,000 for a principal diagnosis of coronary heart disease to 4,600 for rheumatic heart disease.

Age and sex

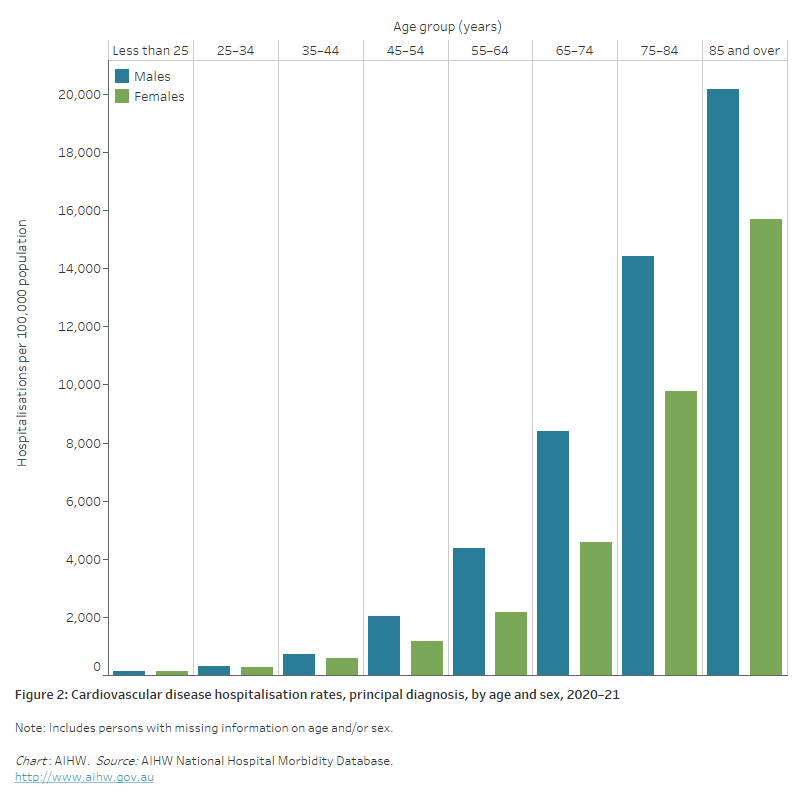

In 2020–21, rates of hospitalisation with CVD as the principal diagnosis:

- were 1.6 times as high for males compared with females, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher among males than females across all age groups (Figure 4)

- increased with age, with over 4 in 5 (84%) CVD hospitalisations occurring in those aged 55 and over. CVD hospitalisation rates for males and females were highest in the 85 and over age group—1.4 times as high as those in the 75–84 age group for males and 1.6 times as high among females (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Cardiovascular disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows cardiovascular disease hospitalisation rates by age group in 2020–21. These were highest among men and women aged 85 and over (20,200 and 15,700 per 100,000 population).

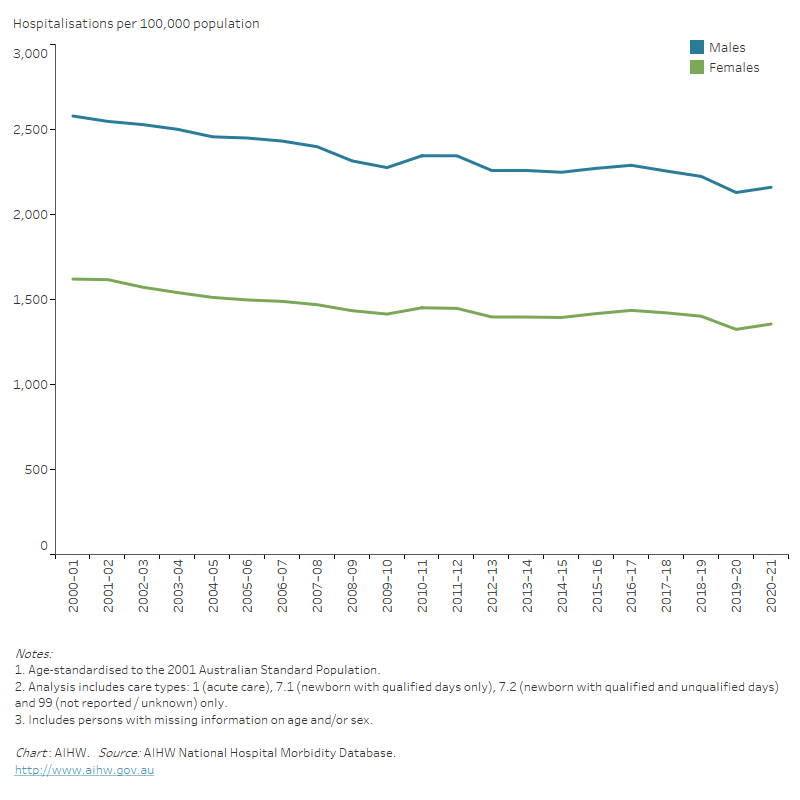

Trends

The number of acute care hospitalisations with CVD as the principal diagnosis increased by 38% between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 393,000 to 542,000 hospitalisations.

Despite increases in the number of hospitalisations, the age-standardised rate declined by 16% over this period, from 2,100 to 1,740 per 100,000 population.

The rate of CVD hospitalisations for males was higher than for females across the period, with both showing similar declines (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Acute care cardiovascular disease hospitalisations rates, principal diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows declines in age-standardised rates of male and female acute care CVD hospitalisations between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 2,570 to 2,160 per 100,000 population for males, and from 1,614 to 1,356 for females.

Length of stay in hospital

The length of time that people spend in hospital for CVD has decreased over the past 3 decades. Among those hospitalised for 1 night or more with CVD as a principal diagnosis, the average length of stay declined from 9.6 days in 1993–94 to 7.9 days in 2007–08 and 5.9 days in 2020–21. In 2020–21, 28% of people admitted to hospital with CVD were discharged the same day.

Of those hospitalised with CVD in 2020–21, patients with stroke tended to stay longest – an average of 11.6 days, followed by patients with congenital heart disease (9.2 days) peripheral arterial disease (6.7 days), and coronary heart disease (4.3 days).

Average length of stay in hospital increases with age. Those aged 85 and over stayed an average of 7.1 days, compared with 4.9 days for those aged 25–34 years. The longer lengths of stay among older people reflect the increased complexity and multiplicity of their conditions.

Variation among population groups

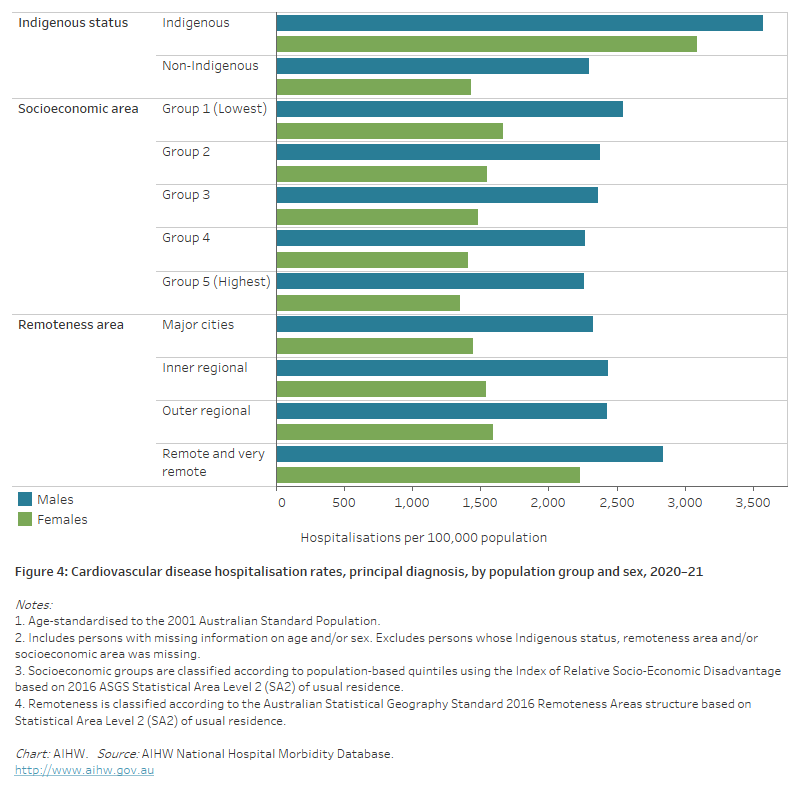

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 17,300 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of CVD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a rate of 2,000 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 1.8 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate

- the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was greater for females—2.2 times as high compared with 1.6 times as high for males.

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, CVD hospitalisation rates were almost 20% higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations .

The disparity between the lowest and highest socioeconomic areas was greater for females than males (1.2 and 1.1 times as high) (Figure 4).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, CVD hospitalisation rates were around 40% higher among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those in Major cities, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations.

This largely reflects disparities in female rates (1.5 times as high), compared to male rates (1.2 times as high).

Higher hospitalisation rates in Remote and very remote areas are likely to be influenced by the higher proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in these areas, who have higher rates of CVD than other Australians.

CVD patients are often transferred from a local regional hospital to a larger urban hospital where more intense or critical care can be provided. In 2020–21, 19% of CVD hospitalisations (principal and/or additional diagnosis) in Remote and very remote areas were transferred to another acute hospital, compared with 16% in Outer regional areas, 14% in Inner regional areas and 9% in Major cities.

The higher rates of transfers are often necessary because certain cardiac procedures, such as angiograms and cardiac revascularisation, are generally performed in large hospitals, which are predominantly located in urban areas.

Figure 4: Cardiovascular disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows that male and female CVD hospitalisation rates in 2020–21 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas, and people living in remote and very remote areas.

Hospital procedures

This section reports on a range of common procedures which diagnose or treat CVD, and are performed on patients admitted to hospital.

Coronary angiography

Coronary angiography is a diagnostic procedure which provides a picture of the coronary arteries – those that supply blood to the heart itself – to determine whether they may be narrowed or blocked. A catheter is guided to the heart where a special dye is released into the coronary arteries before X-rays are taken.

Coronary angiography provides medical professionals with the information to decide on treatment options, such as the need for coronary revascularisation procedures.

- In 2020–21, there were 146,000 coronary angiography procedures reported for patients admitted to hospital – 97,200 (67%) for males and 48,900 (33%) for females.

- Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, the age-standardised rate of coronary angiography procedures in males increased from 572 to 652 per 100,000 population (14%), and from 263 to 295 per 100,000 population (12%) in females.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is a diagnostic procedure which takes moving pictures of the heart using high frequency sound waves (ultrasound).

With these it is possible to measure the size of the various heart chambers, to study the appearance and motions of the heart valves, and to assess blood flow through the heart.

Imaging services, including intraoperative ultrasounds are not usually coded on hospital records, although transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) are an exception and are generally coded. Note, however, that the numbers reported here may be underestimates.

- In 2020–21, there were 49,000 echocardiography procedures reported for patients admitted to hospital – 33,100 (68%) for males and 15,500 (32%) for females.

- The age-standardised rate of echocardiography procedures was 225 per 100,000 population in males, and 99 per 100,000 population in females.

Percutaneous coronary interventions

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) restore blood flow to blocked coronary arteries. There are two types: coronary angioplasty without stent, and coronary stenting.

Coronary angioplasty involves inserting a catheter with a small balloon into a coronary artery, which is inflated to clear the blockage. Coronary stenting is similar, but involves inserting a stent (an expandable mesh tube) into the affected coronary arteries.

- In 2020–21, 48,000 PCIs were performed on patients admitted to hospital – 36,100 (75%) for males and 12,000 (25%) for females (Figure 1).

- Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, the age-standardised rate of PCIs increased from 178 to 243 per 100,000 population (37%) in males, and from 57 to 72 per 100,000 population (26%) in females.

Coronary artery bypass grafting

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a surgical procedure that uses blood vessel grafts to bypass blockages in the coronary arteries and restore adequate blood flow to the heart muscle. The surgery involves taking a blood vessel from a patient’s inner chest, arm or leg and attaching it to the vessels on the outside of the heart to bypass a blocked artery.

- In 2020–21, there were 12,700 CABG procedures performed on patients admitted to hospital – 10,500 (83%) for males and 2,200 (17%) for females (Figure 1).

- Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, the age-standardised rate of CABG decreased from 140 to 69 per 100,000 population (–51%) in males, and from 39 to 13 per 100,000 population (–67%) in females.

- Although rates of CABG have declined, the procedure remains a recommended treatment for certain patients with complex cardiovascular conditions (NHF & CSANZ 2016).

Figure 5: Percutaneous coronary interventions and coronary artery bypass grafts, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows that the number of percutaneous coronary interventions for both males and females increased between 2000–01 and 2020–21, whereas the number of coronary artery bypass grafts declined.

Heart valve repair or replacement

Heart valve repair or replacement procedures are performed when the normal flow of blood through the heart is disrupted by damaged valves, making it harder for the heart to pump blood effectively. This can lead to heart failure. The damage to heart valves may be caused by acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease, coronary heart disease, or forms of congenital heart disease.

- In 2020–21, there were 12,000 heart valve repair or replacement procedures performed on patients admitted to hospital – 7,600 (64%) for males and 4,400 (36%) for females.

- The age-standardised rate of heart valve repair or replacement procedures was 52 per 100,000 population in males, and 26 per 100,000 population in females.

Pacemaker insertion

Pacemakers are small devices that are placed in the chest or abdomen to help control abnormal heart rhythms. These devices use electrical pulses to prompt the heart to beat at a normal rate.

- In 2020–21, there were 19,900 pacemaker insertion procedures performed on patients admitted to hospital – 11,900 (60%) for males and 8,000 (40%) for females.

- The age-standardised rate of pacemaker insertion procedures was 79 per 100,000 population in males, and 44 per 100,000 population in females.

Cardiac defibrillator implant

A cardiac defibrillator implant is a device implanted into a patient’s chest that monitors the heart rhythm and delivers electric shocks to the heart when required to eliminate abnormal rhythms. They are effective in preventing sudden cardiac death in people at high risk of the life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia known as ventricular fibrillation.

- In 2020–21, there were 4,000 cardiac defibrillator implant procedures performed on patients admitted to hospital – 3,100 (77%) for males and 909 (23%) for females.

- The age-standardised rate of cardiac defibrillator implant procedures was 21 per 100,000 population in males, and 5.9 per 100,000 population in females.

Carotid endarterectomy

Carotid endarterectomy is a procedure where atherosclerotic plaques are surgically removed from the carotid arteries in the neck, which supply blood to the brain. This procedure is used to reduce the risk of stroke caused by blockage.

- In 2020–21, there were 1,900 carotid endarterectomy procedures performed on patients admitted to hospital – 1,400 (71%) for males and 550 (29%) for females.

- The age-standardised rate of carotid endarterectomy procedures was 8.9 per 100,000 population in males, and 3.2 per 100,000 population in females.

Heart transplants

A heart transplant involves implanting a working heart from a recently deceased organ donor into a patient. It is generally used to treat severe forms of heart failure or coronary artery disease.

- In 2020–21, there were 129 heart transplants performed – 84 (65%) for males and 45 (35%) for females.

- The age-standardised rate of heart transplants was 0.6 per 100,000 population in males, and 0.3 per 100,000 population in females.

The Australian and New Zealand Organ Donation Registry (ANZOD) records and reports on organ donation within Australia and New Zealand. Of the 421 deceased organ donors in 2021 in Australia, 117 (28%) had a heart retrieved. From these heart donors there were 112 heart transplant recipients. Of these, 4 received heart/double lung transplants and 2 received a combined heart/kidney transplant (ANZOD 2022).

AIHW 2022. MyHospitals. Admitted patients. Hospital resources 2020–21 tables. Table 5.6. Canberra: AIHW.

ANZOD (Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation Registry) 2022. ANZOD Annual Report 2022. ANZOD: Adelaide.

NHF (National Heart Foundation of Australia) & CSANZ (Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand) 2016. Australian clinical guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2016. Heart, Lung and Circulation 25: 895–951.

Stroke Foundation 2021. National Stroke Audit—acute services report 2021. Melbourne: Stroke Foundation.