Aged care service use by First Nations people with dementia

First Nations people accessing government-subsidised aged care services tend to be younger and use these services at higher rates as a proportion of the population than non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2021). Differences in use are due to various factors, including (but not limited to):

- government policies: First Nations people are identified as 1 of 10 'special needs groups' under the Aged Care Act 1997. As a result of the specific needs of First Nations people, planning for aged care services focuses on First Nations people aged 50 and over rather than age 65 and over for non-Indigenous Australians. However, ultimately, access to aged care services is based on the care needs of each individual. In 2019, the Australian Government published an action plan to support the Aged Care Diversity Framework and address barriers faced by older First Nations people when accessing aged care. For a brief overview of Australia’s aged care system, see Overview of Australia's aged care system.

- preferred care types and availability of services: Eligible older Australians have access to a variety of government-subsidised services. However, First Nations people may face challenges with accessing services that provide culturally appropriate care. Older First Nations people generally wish to remain in their communities and on Country for as long as possible, and to have access to culturally safe health and aged care services in their own communities, as well as away from their communities when needed. While all government-subsided aged care services are available to First Nations people and should be designed to provide them with appropriate care, there are First Nations-specific services available (and often preferred) such as the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program (NATSIFACP). The aim of this program is to provide quality, flexible aged care for older First Nations people, in a culturally safe environment. Associated NATSIFACP providers work mainly in regional, remote, and very remote areas, and help First Nations people with home care, emergency or planned respite, short-term care and permanent residential care. At 30 June, 2020, NATSIFACP offered almost 1,300 places. It is also important to note that Stolen Generations survivors were all aged 50 and over and eligible for aged care services by the year 2022 – refer to Box 12.1 for more information on this group and how their life experiences could impact their care needs.

- population age structures: both First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians are experiencing population ageing, but First Nations people have a younger age structure compared to non-Indigenous Australians.

- health status: health conditions associated with ageing and with an increased risk of developing dementia are often more common and begin at younger ages among First Nations people. Rates of aged care use are also generally higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians.

This page presents information on how First Nations people use aged care services based on data on comprehensive assessments undertaken for people wanting to access government-subsidised aged care services and for those receiving government-subsidised permanent residential aged care. These data have limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the information presented, including that there is incomplete information on First Nations-specific aged care services. For example, data from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program are not included.

Box 12.1: Providing effective health and aged care to Stolen Generations survivors

There were about 33,600 survivors of the Stolen Generations in 2018–19, all are now aged 50 and over and eligible for aged care services (AIHW 2021).

Under racially motivated policies, between 1910 and the 1970s, as many as 1 in 3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in institutions or adopted by non-Indigenous Australian families, where they often experienced trauma and human rights violations (AIHW 2021). These children have become known as the 'Stolen Generations'.

Stolen Generations survivors are more likely to experience a range of health, cultural and socioeconomic adverse outcomes compared to other First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians. Childhood stress and trauma has also been linked as a risk factor for developing dementia in later life among First Nations people (Radford et al. 2019).

While Stolen Generations survivors often prefer health and aged care services tailored to First Nations people and to receive care in their own homes and communities, these options are not always available. Leading advocacy and expert organisations have called for urgent government action to provide culturally appropriate support and aged care options to survivors (Healing Foundation and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ageing Advisory Group of the Australian Association of Gerontology 2019). Residential aged care and clinical settings that resemble childhood institutions where removed children were placed can re-trigger trauma (Smith and Gilchrist 2017), so it is essential that health and aged care providers understand the effects of trauma and that care is culturally appropriate and safe (Healing Foundation 2019).

In its final report, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety echoed the importance of providing Stolen Generations survivors with appropriate aged care options and further highlighted the importance of '… accessible pathways linking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to the care that they need. To deliver culturally safe pathways to aged care … the Australian Government should ensure that care finders serving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people' (Royal Commission 2021).

Assessment for use of aged care services

Access to government-subsidised aged care services is co-ordinated through the My Aged Care system, in which, after an initial screening to determine eligibility, a person's needs and types of services are assessed using the National Screening and Assessment Form (NSAF). There are 2 main types of aged care assessments depending on the level of care needed:

- home support assessments – face-to-face assessments provided by Regional Assessment Services for people seeking home-based entry-level support that is provided under the Commonwealth Home Support Programme

- comprehensive assessments – provided by Aged Care Assessment Teams for people with complex and multiple care needs to determine the most suitable type of care (home care, residential or transition care). Dementia is a condition commonly prompting a comprehensive assessment (Ng and Ward 2019).

See Aged care assessments for more information on aged care assessments and the types of services available.

Information on people with dementia who completed a comprehensive and/or home support assessment in 2021–22 is available from NSAF data as part of the National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse.

Aged care assessments

In 2021–22, just over 8,500 people, or 2.4% of all people who completed an aged care assessment (either a comprehensive or home support assessment) identified as being a First Nations person. Dementia was recorded as a condition contributing to the care needs of 480 First Nations people, or 5.6% of all First Nations people who completed an aged care assessment in 2021–22.

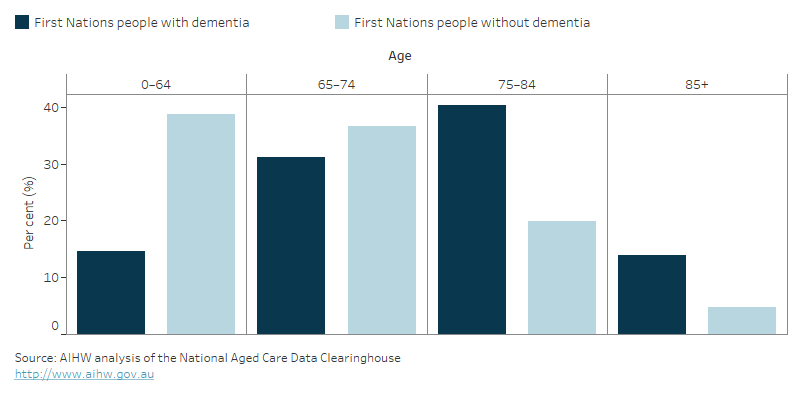

Among First Nations people who completed an aged care assessment in 2021–22, those with dementia were older than those without dementia. Over half (54%) of First Nations people with dementia were aged 75 and over compared with 25% of First Nations people without dementia (Figure 12.14).

An additional 300 First Nations people with cognitive impairment (but no record of dementia) completed an aged care assessment

This equates to 3.5% of First Nations people who completed an aged care assessment in 2021–22.

This group includes people with mild cognitive impairment – where they have significant memory loss but no other changes in cognitive function. Mild cognitive impairment increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but it does not mean that the development of dementia is certain. However, it is recognised that some people with cognitive impairment who complete an aged care assessment may be in the early stages of dementia and are yet to receive a formal diagnosis. Therefore, the number of First Nations people with dementia in this report may be an underestimate of the true number of First Nations people with dementia seeking entry into aged care services.

Figure 12.14: First Nations people with and without dementia who completed an aged care assessment in

2021–22: percentage, by age

This figure shows the age profile of First Nations people with and without dementia who completed an aged care assessment.

The majority of First Nations people with dementia (94%) who completed an aged care assessment were living in the community at the time of their assessment. First Nations people with dementia were more likely to be living with family (40% of First Nations people with dementia living in the community) than non-Indigenous Australians with dementia (18%) (Table S12.24).

Assessment type and setting

Dementia is a common reason for needing a comprehensive assessment. Around 4 in 5 First Nations people with dementia who completed an assessment in 2021–22 (79% or 378 people) completed a comprehensive assessment rather than a home support assessment (21% or 99 people).

Over half (56%) of First Nations people with dementia who completed a comprehensive assessment and 88% who completed a home support assessment, completed the assessment in their own home. Comprehensive assessments can also take place in a hospital, and 1 in 4 First Nations people with dementia (26%) completed their comprehensive assessment while in a hospital setting.

Co-existing health conditions

People with dementia typically have other co-existing conditions that impact care needs.

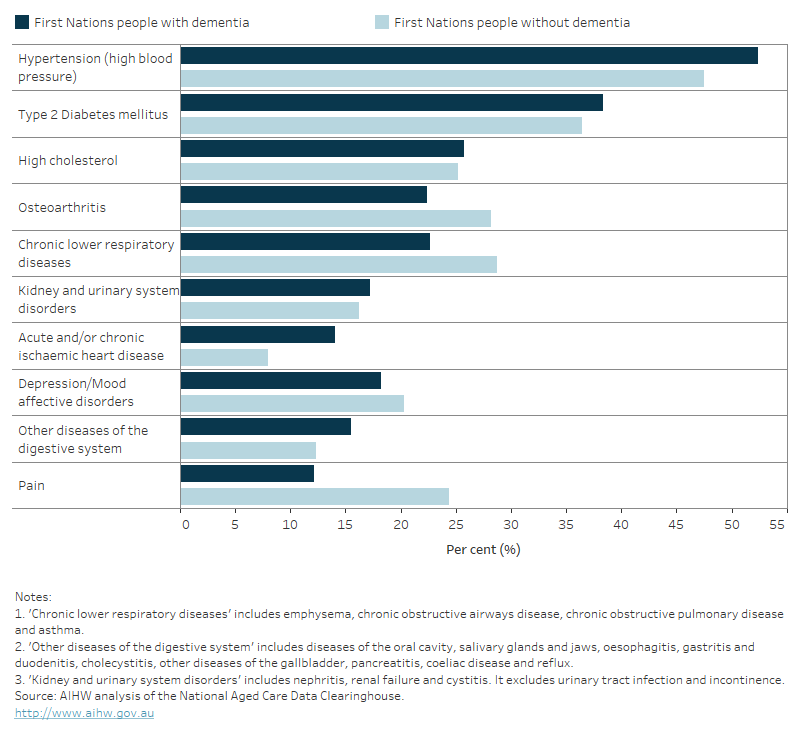

The most common conditions among First Nations people with dementia who completed an aged care assessment in 2021–22 were:

- high blood pressure (52% of all First Nations people with dementia)

- type 2 diabetes mellitus (38%)

- high cholesterol (26%)

- chronic lower respiratory diseases (23%)

- osteoarthritis (22%) (Figure 12.15).

Figure 12.15: Leading 10 health conditions among First Nations people who completed an aged care assessment in 2021–22: percentage, by dementia status

This bar chart shows the top 10 comorbidities of First Nations Australians with and without dementia who completed an aged care assessment in 2021–22.

Approvals for use of aged care services

Assessors recommend and approve people for entry into a range of government-subsidised aged care services based on a person’s long-term care needs. Approvals are not only provided for immediate use of services but also for future use if a person’s care needs are likely to change. This means that people can be approved for multiple services.

Of the First Nations people with dementia who completed a comprehensive assessment in 2021–22:

- 66% or 249 people were approved for residential respite care

- 62% or 235 people were approved for community-based care under the Home Care Packages Program

- 58% or 220 people were approved for permanent residential aged care.

Approvals for people with dementia who completed a home support assessment were not readily available in the NSAF data.

Use of permanent residential aged care

This section presents data from Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) appraisals to describe the characteristics of First Nations People with dementia living in permanent residential aged care. The ACFI is a funding tool used by the Australian Government to allocate funding to providers based on the ongoing care needs of people living in residential aged care. See Residential aged care for more details on the ACFI and residential aged care provision in Australia.

During 2020-21, about 241,000 people were living in permanent residential aged care services across Australia. Of these, just under 2,600 (1%) identified as being First Nations. About half (53% or 1,370) of the First Nations people living in permanent residential aged care had dementia.

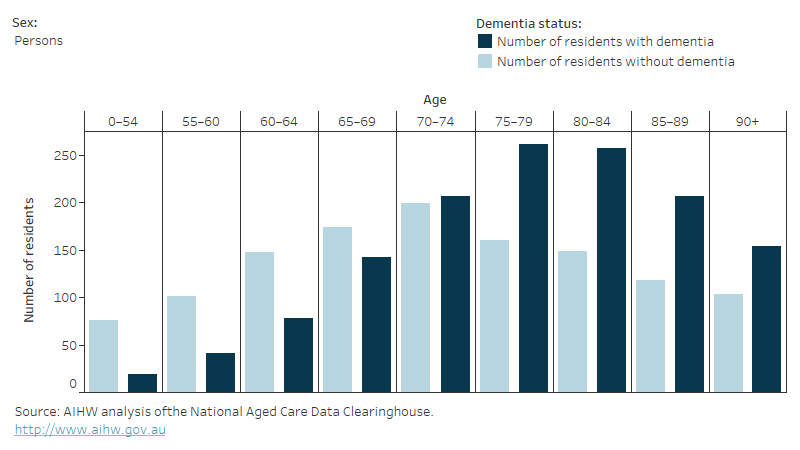

Figure 12.16 shows the age profile of First Nations people living in permanent residential aged care by dementia status. First Nations men and women with dementia were older than First Nations people without dementia.

Figure 12.16: First Nations people living in permanent residential aged care 2021–22: number, by dementia status, age and sex

A bar chart showing the number of First Nations people living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22 by age and sex. The number of First Nations people with dementia living in residential aged care increases with age until 75 to 79. Both First Nations men and women with dementia were older than First Nations men and women without dementia living in residential aged care.

The number of First Nations people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care has increased in recent years from just under 1,100 in 2014–15 to just under 1,370 in 2021–22. Consistently, just over 50% of First Nations people living in permanent residential aged care were living with dementia during this 7-year period.

Time spent living in permanent residential care

A person can have more than one episode of care in a residential aged care facility in a given year if, for example, they moved from one facility to another. A separation from an 'episode of care' is most commonly due to: death, prolonged admission to hospital, movement to another residential aged care facility, or returning to the community. First Nations people with dementia who separated from their latest episode of care during 2021–22 had a median stay of 2.2 years, with the majority of separations due to death (87%).

Use of residential aged care services by state/territory and remoteness area

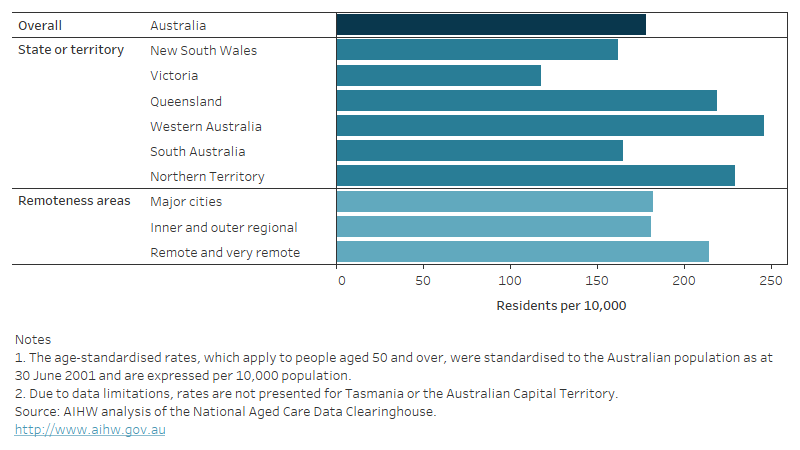

Figure 12.17 shows how the age-standardised rate of permanent residential aged care use among First Nations people varied by dementia status and across geographic areas in 2021–22. After accounting for population differences:

- across states and territories, the rate of permanent residential aged care use for First Nations people with dementia was highest in Western Australia (246 people with dementia per 10,000 First Nations people) and lowest in New South Wales and Victoria (162 and 119 people with dementia per 10,000 First Nations people, respectively). Due to data limitations, rates for Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory are not included

- First Nations people with dementia tended to use permanent residential aged care services at higher rates in more remote areas – 214 people with dementia per 10,000 First Nations people in Remote and very remote areas compared with 181 and 182 people with dementia per 10,000 First Nations people in Inner and outer regional areas and Major cities, respectively.

Figure 12.17: First Nations people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care 2021–22: age standardised rate, by state/territory and remoteness

A bar graph showing the age standardised rate of First Nations people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22 by state and territory and remoteness area.

Co-existing health conditions

The ACFI collects information on health conditions that impact on a person’s care needs. This includes up to 3 mental and behavioural disorders (including dementia), as well as three medical conditions impacting care needs.

During 2021–22, depression and mood disorders (40%), arthritis and related disorders (36%), and urinary incontinence (28%) were the 3 most common health conditions among First Nations people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care (Table S12.32). Other common conditions included: type 2 diabetes mellitus (23%), hypertension (17%), pain (16%), anxiety and stress related disorders (16%), chronic lower respiratory diseases (16%), stroke (12%), falls (9.2%), kidney and urinary system disorders (8.7%) and other mental and behavioural disorders (8.1%).

Care needs

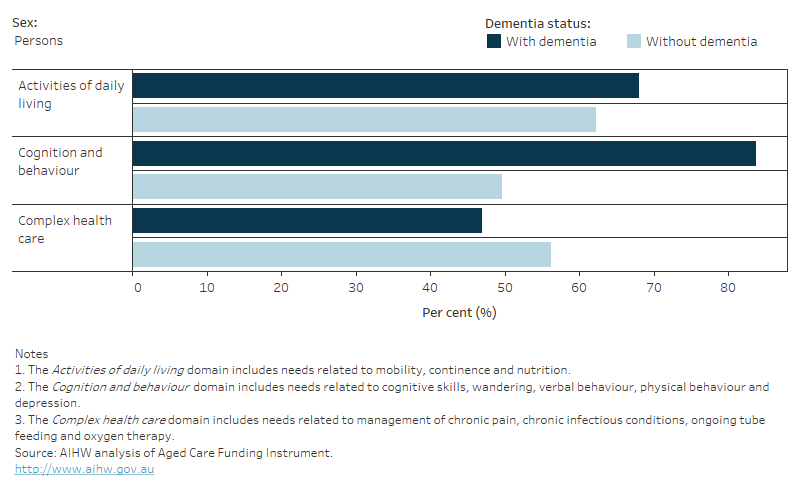

The ACFI determines the funding allocation for a resident based on the level of care they require in three domains: Activities of daily living, Cognition and behaviour and Complex health care.

Among First Nations people with dementia who were living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22:

- 68% required high levels of care related to Activities of daily living (such as nutrition, mobility, personal hygiene, toileting and continence needs) – this was slightly higher than for First Nations people without dementia (62%)

- 84% required high levels of care related to their Cognition and behaviour, which includes cognitive skills, wandering, verbal behaviour, physical behaviour and depression – this was higher than for First Nations people without dementia (50%)

- 47% required high levels of care related to Complex health care, which includes ongoing medication needs and complex health-care procedures – this was lower than for First Nations people without dementia (56%)

For each ACFI domain, there was little difference in percentage of men and women with dementia with the highest care needs. It is important to remember that many First Nations people access comprehensive care outside their home that is not captured in the ACFI data, such as through the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program, so information presented in this report does not comprehensively capture the care needs of all First Nations people accessing residential aged care services.

Figure 12.18: First Nations people living in permanent residential aged care with the highest care needs in each ACFI domain 2021–22: percentage, by sex and dementia status

A bar chart showing the percentage of First Nations people living in residential aged care with and without dementia who required high levels of care in each ACFI domain in 2021–22 by sex.

AIHW (Australian institute of Health and Welfare) (2019) Aged care for Indigenous Australians, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 June 2023.

AIHW (2021) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations aged 50 and over: updated analyses for 2018–19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 June 2023.

Healing Foundation (2019) Working with the Stolen Generations: understanding trauma. Providing effective aged care services to Stolen Generations survivors, Healing Foundation website, accessed 26 June 2023.

Healing Foundation and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ageing Advisory Group of the Australian Association of Gerontology (2019) Stolen Generations aged care forum report August 2019, Royal Commission in Aged Care Quality and Safety website, accessed 26 June 2023.

Ng NSQ and Ward SA (2019) ‘Diagnosis of dementia in Australia: a narrative review of services and models of care’, Australian Health Review, 43(4):415–424, doi:10.1071/AH17167.

Radford K, Lavrencic LM, Delbaere K, Draper B, Cumming R, Daylight G, Mack HA, Chalkley S, Bennett, H, Garvey G, Hill TY, Lasschuit D and Broe GA (2019) ‘Factors associated with the high prevalence of dementia in older Aboriginal Australians’, Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 70(s1):S75–S85, doi:10.3233/JAD-180573.

Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety) (2021) Final report: Care, dignity and respect, Royal Commission, Australian government, accessed 26 June 2023.