Dementia among people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

Australia has a long and rich history of immigration, and as a result, the Australian population includes a large number of people who were born overseas, have a parent born overseas and/or who speak a variety of languages. These groups of people are generally referred to as culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations. However, it is not always easy to identify CALD people or populations in data because the relevant information is not always systematically recorded. As a result of these limitations, this section mainly uses both country of birth and main language spoken at home to identify CALD populations.

Understanding dementia with respect to people of CALD backgrounds is essential for health and aged care policy and planning, as research suggests that the CALD community, or specific cultural subgroups may experience different patterns of disease, health risk factors and access to and utilisation of services (AIHW 2018). Widespread use of appropriate dementia diagnostic tools (such as the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS)) are needed to ensure diagnosis is not further delayed due to communication and cultural differences. Further, as people with dementia who can speak multiple languages will often revert to their first language or mix languages as their dementia progresses, this can lead to communication barriers that can cause feelings of isolation, loneliness, and anxiety and depression in those with dementia and result in their needs not being met.

Until more information is available, this page aims to explore dementia in CALD communities in Australia, using the currently available national data, by:

- examining patterns of cultural and linguistic diversity in people living with dementia

- assessing the use of permanent residential aged care services by people with dementia from CALD backgrounds and how this compares with people from English speaking backgrounds (skip to this section)

- examining the source of assistance for people with dementia from CALD backgrounds and how this compares with people from English speaking backgrounds (skip to this section)

- exploring CALD among primary carers of people with dementia (skip to this section).

See Cultural linguistic diversity among Australians who died with dementia for patterns of CALD among people who died with dementia, using linked Census and mortality data. For more information on this priority population group, see culturally and linguistically diverse Australians.

Expand the sections below for more information on what data are available to report on dementia in Australia’s CALD communities, limitations of these data and what is being done to improve them.

According to the 2021 Census of Population and Housing, 7 million people residing in Australia at the time of being surveyed were born overseas (ABS 2022). The birthplace composition of Australia’s older population, 65 years and over, is largely reflective of the waves of migration that have occurred since World War Two (Wilson et al. 2020). The oldest Australians today who were born overseas primarily come from the British Isles and New Zealand, followed by Western and Eastern Europe. This migration wave was followed by Southern Europe, particularly Italy, Malta and Greece. A recent study by the University of Melbourne projects an increase in the population of overseas born Australians, which will shift from European-born dominance to Asia-born dominance (Wilson et al. 2020). As age is one of the most prominent risk factors for dementia, the birthplace composition of older age groups in Australia gives insight into the communities that may be impacted by dementia. In addition, changes in migration patterns also need to be considered with respect to the aged care workforce, particularly differences in languages other than English spoken among aged care workers compared with their older care recipients.

Due to the limited national data on dementia that includes identifiers of culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia, data in this report are limited to:

- ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) – is a national survey which collects information about 3 target populations: people with disability (that is, those who have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts every-day activities), people aged 65 or over, and people who care for individuals with disability, or older people. These data identify Australians with dementia and record country of birth, main language spoken and English language proficiency.

- The Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) data set (a data holding within the National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse (NACDC)) – these data identify people with dementia who are living in permanent residential aged care, as well as recipient demographic data (including country of birth and main language spoken) that can be linked to the ACFI.

- Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) – a partnership among Australian Government agencies to develop a secure and enduring approach for combining information on healthcare, education, government payments, personal income tax, and population demographics (including the Census) to create a comprehensive picture of Australia over time. For this report, people who died with dementia were identified using mortality data and their country of birth, ancestry, year of arrival, language spoken at home, religion and English language proficiency were derived from the 2016 Census.

Note, these data sources draw from different population groups and do not represent all Australians with dementia. For example, dementia is only recorded if it contributes to a persons’ limitation, restriction or impairment in the SDAC; if it is a main condition impacting care needs in the ACFI; and if it is on a persons’ death certificate as an underlying or associated cause of death in MADIP. Not all people with dementia are captured by these data.

Unfortunately, there are few national data sources that provide insight on the CALD community living with dementia in Australia. The Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia (FECCA) (2015) concluded that while there is a substantial body of research available evaluating the culturally sensitive tools for dementia diagnosis, there is little known about the experience of older CALD Australians with dementia, including diagnostic rates, age of onset, their experiences and interactions with medical professionals as well as broader health, aged care and social support services.

More high-quality data on CALD among people with dementia are required for service planning and development. To highlight and address these gaps, the then National Health and Medical Research Councils National Institute of Dementia Research (NNIDR) and the National Ageing Research Institute (NARI) published a CALD Dementia Research Action Plan. The plan aims to increase CALD inclusion in dementia research (NNIDR and NARI 2020).

The Australian Clinical Trials Alliance (2020a) has also published a position statement with guiding principles on recognising underrepresentation of people from CALD backgrounds and how to increase and enhance diversity in clinical trials. A review of national and international initiatives was also undertaken that have aimed to increase participation in clinical trials by ethnic minority groups. This aims to understand how to improve and develop clinical trial awareness, involvement and access for the CALD populations of Australia, and if successful, could offer a greater insight into Australia’s CALD population living with dementia (Australian Clinical Trials Alliance 2020b).

There are a number of risk factors for dementia which people born in certain countries may experience at different rates compared to people who were born and live in Australia. This includes increased mortality and hospitalisations rates from type 2 diabetes mellitus and self-reported mental health conditions (AIHW 2005; Jatrana et al. 2017). However, people from CALD backgrounds are less likely to report drinking alcohol at harmful levels and are more likely to report that they have never smoked than English speakers (AIHW 2020). More research is needed on the current prevalence of risk factors for dementia among people in Australia from CALD backgrounds, including sub-populations in the CALD community and how these are changing over time.

New health condition question in the 2021 Census

For the first time, the 2021 ABS Census of Population and Housing collected information from respondents on selected health conditions. This new question enables examination of self-reported dementia by a wide range of demographic information, including for CALD communities.

Some key findings for dementia include:

- Those born in Italy had the highest rate of dementia after controlling for age differences.

- The rate of dementia increased as proficiency in English decreased.

- The longer that migrants have been in Australia, the higher the rate of dementia.

For further information on dementia and other chronic health conditions among CALD communities, see the following web report: Chronic health conditions among culturally and linguistically diverse Australians, 2021.

CALD among Australians with dementia

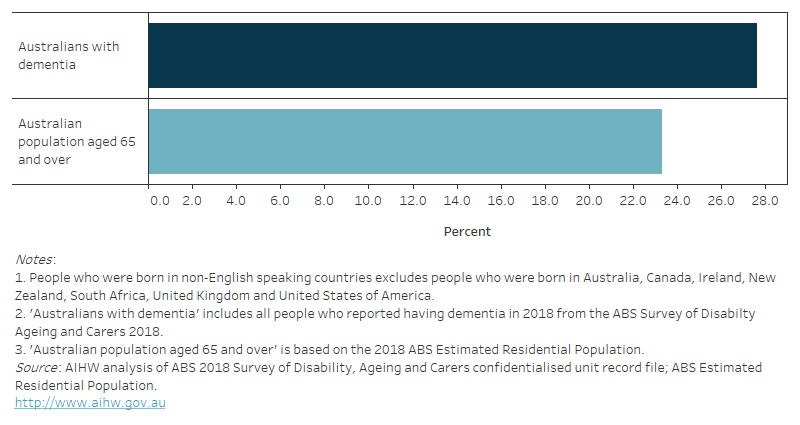

According to the SDAC, in 2018, 28% of people with dementia in Australia were born in a non-English speaking country (Figure 13.1). This proportion is slightly greater than what is reported for all Australians aged 65 and over in 2018 according to the ABS Estimated Resident Population (23% of Australians aged 65 and over were born in a non-English speaking country).

Italy was the most common non-English speaking country of birth among those with dementia, accounting for 3.5% of all people with dementia in 2018. This is largely reflective of the post-World War II migration of Italians to Australia (ABS 2020). Greece and China were the next most common non-English speaking countries of birth among those with dementia (3.0% and 2.2%, respectively) (Table S13.2).

The SDAC also collected information on English proficiency for those whose main language spoken at home was not English. Around 62% of people with dementia whose main language was not English, reported that they either did not speak English or if they spoke English they did not speak it well (Table S13.3).

Figure 13.1: Cultural and linguistic diversity among people with dementia and Australians aged 65 and over in 2018: percentage who were born in non-English speaking countries

Figure 13.1 is a bar graph showing the percentage of people who were born in a non-English speaking country among Australians with dementia and all Australians aged 65 and over, in 2018. It shows that a slightly higher proportion of Australians with dementia were born in a non-English country (28%), compared with all Australians aged 65 and over (23%).

It is important to note that there are a number of issues with using the SDAC to report on people with dementia, and further for those with dementia from CALD backgrounds. The SDAC may underestimate the number of people with dementia living in the community as it relies on people in the community self-reporting their health condition rather than a medical assessment. Issues of stigma associated with dementia may affect the likelihood that a person reports their condition in this survey, and this may vary depending on cultural background. In addition, language barriers and cultural practices may affect when people are diagnosed with dementia, meaning that people from CALD backgrounds may have greater levels of undiagnosed dementia than other Australians, especially among those who are not living in residential aged care. However, the use of proxy interviews for SDAC respondents who experience language barriers would minimise this issue. Despite this, the proportion of people with dementia from CALD backgrounds may still be underestimated by the SDAC data.

Level of disability

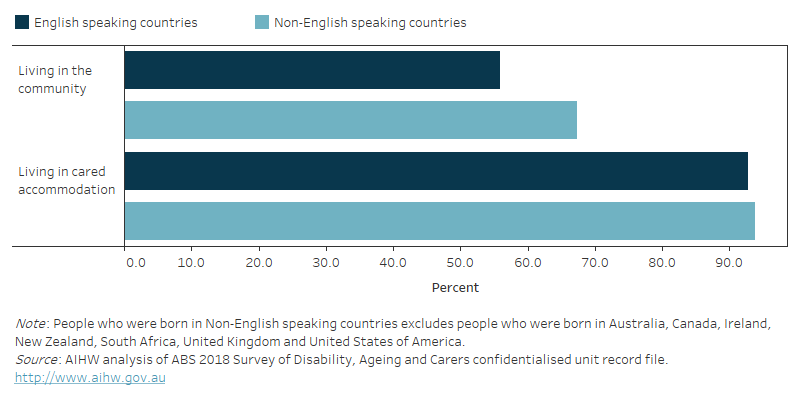

According to the SDAC, in 2018, 67% of people with dementia who were born in non-English speaking countries and were living in the community had profound limitations. That is, they are unable to do, or always need help with self-care, communication and/or mobility (Figure 13.2). By comparison, 56% of people with dementia who were born in English speaking countries had profound limitations. However, this difference was not statistically significant. There was also no statistically significant difference in the percentage of people with dementia who had profound limitations by region of birth among those living in cared accommodation.

Figure 13.2: People with dementia with profound limitations in 2018: percentage by region of birth and place of residence

Figure 13.2 is a bar graph that shows the percentage of people with dementia who had profound limitations in 2018, by whether they were living in the community or cared accommodation and whether they were born in an English or non-English speaking country. In comparison to people with dementia living in cared accommodation, lower proportions of people with dementia living in the community had profound limitations. Among those living in the community, people born in English speaking countries were less likely to have profound limitations compared with those born in non-English speaking countries (56% versus 67% respectively had profound limitations). Among people living in cared accommodation there was little difference between those who were, and were not, born in English speaking countries.

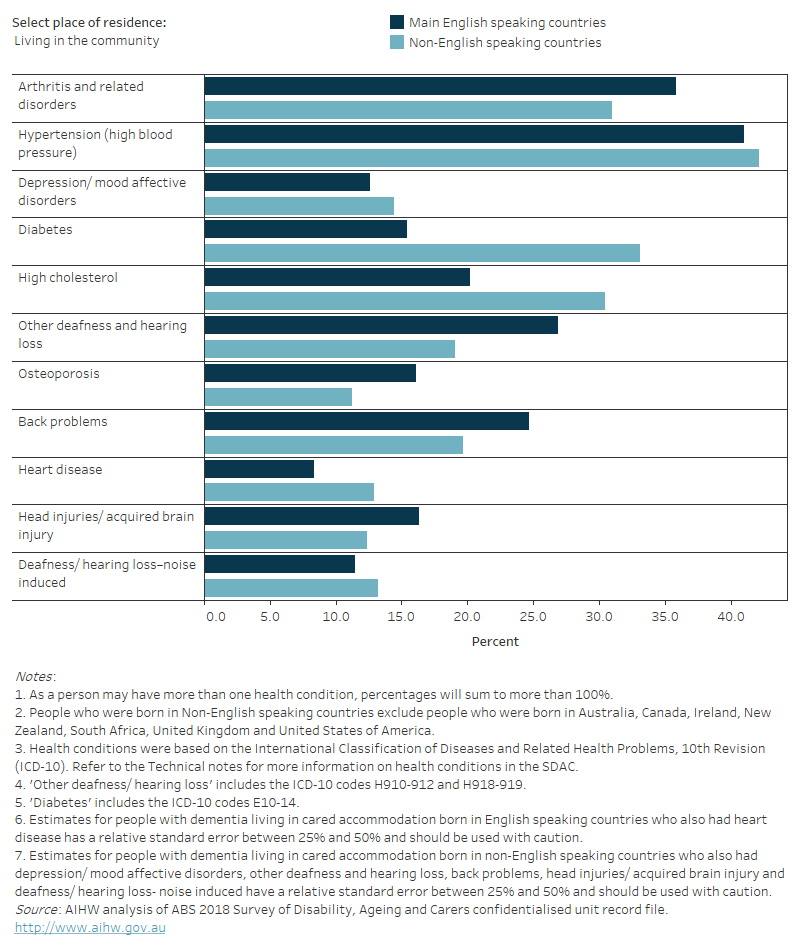

Co-existing health conditions

Based on the SDAC, in 2018, there were some distinct differences in the most common co-existing health conditions of people with dementia between people born in English speaking countries compared with those born in non-English speaking countries (Figure 13.3). These differences were mainly evident among those living in the community.

Among people with dementia living in the community, the following co-existing health conditions were most commonly reported among those who were born in non-English speaking countries:

- hypertension – reported in 42% of people born in non-English speaking countries

- diabetes – 33%

- high cholesterol– 31%

- back problems – 20%

- other deafness/ hearing loss – 19%

- depression – 14%.

Diabetes was reported significantly more among people with dementia born in non-English speaking countries than those born in English speaking countries (15%). There was no significant difference between common co-existing conditions reported by people with dementia born in non-English speaking countries to those born in English speaking countries.

Among people with dementia who were living in cared accommodation, diabetes was reported in 25% of people with dementia from non-English speaking countries compared with 16% of those with dementia born in English speaking countries. For all other health conditions, there were similar patterns between people born in non-English speaking countries and people born in English speaking countries.

The conditions shown in Figure 13.3 (besides back problems, arthritis and osteoporosis) are also known risk factors for dementia. See the What puts someone at risk of developing dementia? for more information.

Figure 13.3: Common co-existing conditions among people with dementia in 2018: percentage by region of birth and place of residence

Figure 13.3 is a bar graph that shows the percentage of people with dementia who had each of the 10 most common health conditions in 2018, by whether the person was born in an English speaking country and place of residence. Arthritis and related disorders, Hypertension (high blood pressure) and Depression/mood affective disorders were the most common conditions among those living in cared accommodation, regardless of whether they were born in a main English speaking country. Among those living in the community Hypertension (high blood pressure) and Arthritis and related disorders were the most common health conditions. Diabetes was more common for those born in non-English speaking countries than for those born in English speaking countries, regardless of place of residence.

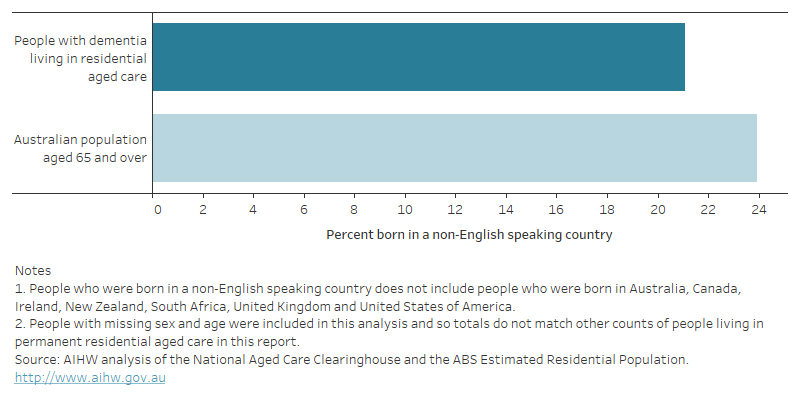

CALD among Australians with dementia living in permanent residential aged care facilities

According to Aged Care Funding Instrument data, 21% of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care facilities in 2021–22 were born in a non-English speaking country (Figure 13.4, see Residential aged care for more detail on this data). This is lower than the proportion of all people with dementia in 2018 as estimated by SDAC (28%). Italy was the most common non-English speaking country of birth among people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care (3.9%). This was followed by mostly European countries, including Greece (2%), Germany (1.4%), and the Netherlands (1.2%).

The smaller proportion of people from CALD backgrounds in permanent residential aged care may reflect differences in how aged care services are used by people from CALD backgrounds. Use of residential aged care is likely to be affected by cultural attitudes to formal aged care services and family obligations or cultural norms for providing care, as well as variation in the availability of culture-specific residential aged care services. For some cultures, the responsibility of caring for the elderly population falls upon kin, and choosing residential care over a family member’s home may be taboo (Rees & McCallum 2018). For people of CALD backgrounds, it can sometimes also be difficult to access and utilise services, if services are not designed with CALD communities in mind and if there are language barriers between service providers and people from non-English speaking backgrounds. Considerations when designing a service accessible to members of the CALD community may include providing information in a number of languages and ensuring the availability of interpreters, food choices, access and respect of cultural practices and family, and general independence (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission 2020).

Figure 13.4: People with dementia living in permanent residential aged care and the Australian population aged 65 and over in 2021–22: percentage who were born in non-English speaking countries

Figure 13.4 is a bar graph that shows the percentage of people who were born in a non-English speaking country among Australians with dementia living in residential aged care compared with all Australians aged 65 and over, in 2021–22. It shows that a slightly lower proportion of Australians with dementia living in residential aged care were born in a non-English country (21%), compared with all Australians aged 65 and over (24%).

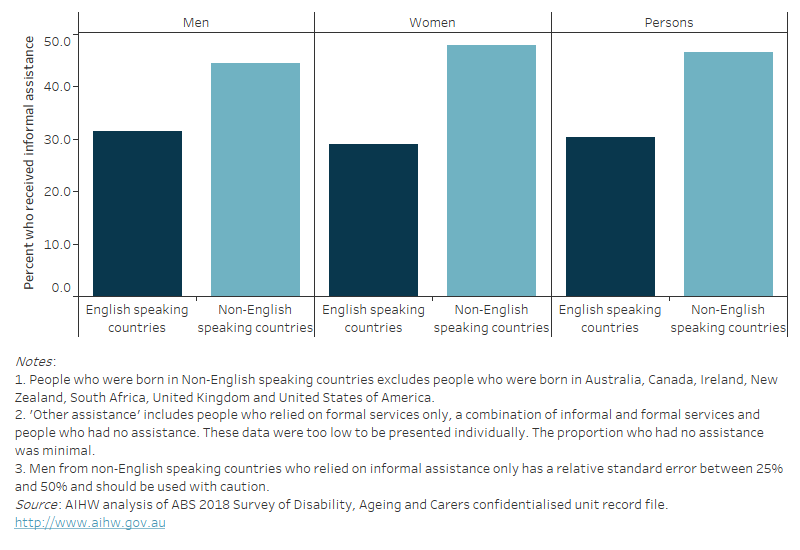

People with dementia from non-English speaking countries are more likely to rely on informal carers only

Based on the SDAC, in 2018 just under half (47%) of people with dementia who were living in the community and were born in non-English speaking countries and 30% who were born in English speaking countries relied on informal assistance only, as opposed to using formal services or a combination of formal services and informal assistance (Figure 13.5).

Among people with dementia, there were only slight differences by sex – 45% of men and 48% of women with dementia who were born in non-English speaking countries relied on informal assistance only. Whereas, 31% of men and 29% of women who were born in English speaking countries relied on informal assistance only.

Figure 13.5: People with dementia who lived in the community and received informal assistance only in 2018: percentages by region of birth and sex

Figure 13.5 is a bar graph that shows the proportion of people with dementia who relied on informal assistance only in 2018 by sex and whether they were born in non-English speaking countries. People born in non-English speaking countries were more likely to rely on informal assistance only—47%, compared with 30% of those born in English speaking countries.

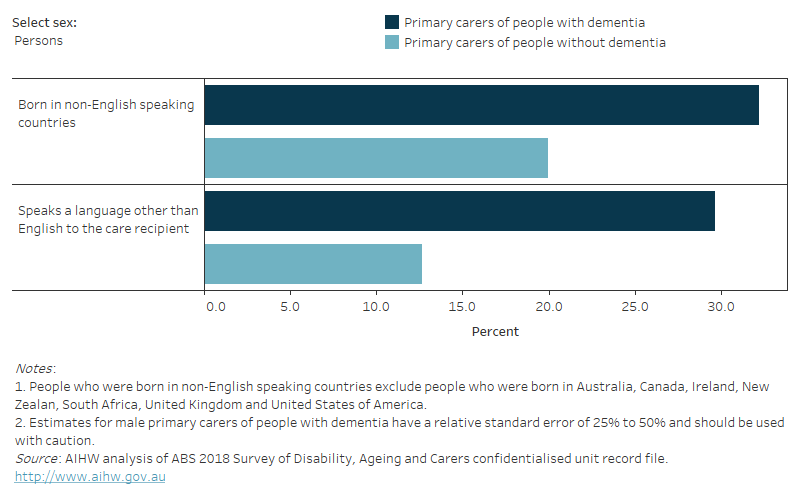

Diversity among primary carers of people with dementia

It is not only the diversity of the people with dementia who need to be considered, but also their support systems (family and friends).

According to the SDAC in 2018:

- 32% of primary carers of people with dementia were born in a non-English speaking country – this was significantly greater than among primary carers of people without dementia (20%).

- 30% of primary carers of people with dementia usually spoke a language other than English to their care recipient – this was also greater than among primary carers of people without dementia (13%) (Figure 13.6).

There was no statistical difference in the proportion of male carers who usually spoke a language other than English to their care recipient with dementia than female carers (36% and 27%, respectively).

Refer to Carers of people with dementia for more information on carers of people with dementia including the relationship of carers to their care recipients.

Figure 13.6: Primary carers of people with dementia and people without dementia in 2018: percentage by sex and CALD characteristics

Figure 13.6 is a bar graph that shows, among primary carers in 2018, the percentage who were born in non-English speaking countries and the percentage who spoke a language other than English to the care recipient. Results are disaggregated by sex and whether the person cared for someone with or without dementia. Overall, nearly 32% of primary carers of people with dementia were born in non-English speaking countries and 27% spoke a language other than English to their care recipient. In comparison, 20% of carers of people without dementia were born in a non-English speaking country and 13% spoke a language other than English to their care recipient.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2022) Cultural diversity of Australia, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 26 June 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2005) Diabetes in culturally and linguistically diverse Australians, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 June 2023.

AIHW (2020) Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 18 September 2020.

AIHW (2021) Older Australia at a glance, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 June 2023.

Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (2020) Working with aged care consumers – Resource, Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, Australian Government, accessed 28 August 2020.

ACTA (Australian Clinical Trials Alliance) (2020a) Advancing clinical trial awareness, involvement and access for people from CALD backgrounds: position statement, ACTA website, accessed 24 August 2021.

ACTA (Australian Clinical Trials Alliance) (2020b) ACTA Clinical trial awareness and access amongst culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations: environmental scan, ACTA website, accessed 28 August 2020.

FECCA (Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia) (2015) Review of Australian Research on Older People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds, FECCA website, accessed 4 July 2023.

Jatrana S, Richardson K and Samba SRA (2017) 'Investigating the dynamics of migration and health in Australia: a longitudinal study', European Journal of Population, 34: 519 – 565, doi:10.1007/s10680-017-9439-z.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council), NNIDR (National Institute for Dementia Research) and NARI (National Ageing Research Institute) (2020) Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Dementia Research Action Plan, NHMRC website, accessed 4 July 2023.

Rees K and McCallum J (2018) Dealing with Diversity: Aged care services for new and emerging communities, National Seniors Australia website, accessed 4 July 2023.

Wilson T, McDonald P, Temple J, Brijnath B and Utomo A (2020) 'Past and projected growth of Australia’s older migrant populations', Genus 76(20), doi:10.1186/s41118-020-00091-6.